5.5. Trị liệu hướng đến nguồn gốc: Khuyến cáo

Class IIa

1. Ức chế ACE hoặc ức chế thụ thể angiotensin (ARB ) là phù hợp cho dự phòng tiên phát cơn khởi phát AF mới ở các bệnh nhân HF có LVEF giảm (148-150). ( Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

Biên dịch: TS Phạm Hữu Văn

{article 1064}• {link}{title}{/link}{/article}

{article 1077}• {link}{title}{/link}{/article}

Class IIb

1. Điều trị bằng thuốc ức chế ACE hoặc ARB có thể được xem xét để dự phòng tiên AF khởi phát mới trong tình trạng tăng huyết áp (34, 151). ( Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

2. Liệu pháp statin có thể hợp lý để phòng ngừa tiên phát AF khởi phát mới sau phẫu thuật động mạch vành ( 152, 153 ). ( Mức độ bằng chứng: A)

Class III: Không có lợi ích

1. Điều trị bằng thuốc ức chế men chuyển, ARB, hoặc statin không có lợi cho dự phòng tiên phát AF ở ở những bệnh nhân không có bệnh tim mạch (34, 154 ). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

5.6.Loại bỏ AF bằng catheter để duy trì nhịp xoang: Khuyến cáo

Class I

1. Loại bỏ AF qua catheter là hữu ích cho AF kịch phát có triệu chứng trơ hoặc kém chịu đựng ít nhất với các thuốc chống loạn nhịp class I hoặc III khi chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp được mong muốn (155-161). (Mức độ bằng chứng: A)

2 . Trước khi xem xét loại bỏ AF qua catheter, đánh giá nguy cơ của thủ thuật và kết quả liên quan đến từng bệnh nhân được khuyến cáo. ( Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class IIa

1. Loại bỏ AF qua catheter là phù hợp cho các bệnh nhân được lựa chọn có AF triệu chứng dai dẳng hay không dung nạp ít nhất các thuốc chống loạn nhịp class I hoặc III (158, 162-164). (Mức độ bằng chứng: A)

2. Ở những bệnh nhân AF kịch phát tái phát có triệu chứng, loại bỏ qua catheter là phù hợp chiến lượng kiểm soát nhịp khởi đầu trước khi các thử nghiệm điều trị của điều trị bằng thuốc chống loạn nhịp, sau khi cân nhắc nguy cơ và kết quả của thuốc và điều trị loại bỏ ( 165-167 ). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

Class IIb

1. Loại bỏ AF qua catheter có thể được xem xét để cho AF dai dẳng (> 12 tháng) kéo dài có triệu chứng, trơ hoặc kém không dung nạp ít nhất các thuốc chống loạn nhịp class I hoặc III, khi chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp được mong muốn (155, 168). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

2. Loại bỏ AF qua catheter có thể được xem xét trước khi bắt đầu điều trị bằng thuốc chống loạn nhịp với nhóm I hoặc III ở AF dai dẳng có triệu chứng, khi một chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp được mong muốn. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class III: Tác hại

1. Loại bỏ AF qua catheter không nên được thực hiện ở những bệnh nhân không thể được điều trị bằng liệu pháp chống đông máu trong và sau thủ thuật. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Loại bỏ AF qua catheter để khôi phục lại nhịp xoang không nên được thực hiện với mục đích duy nhất của phòng ngừa sự cần thiết phải chống đông. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

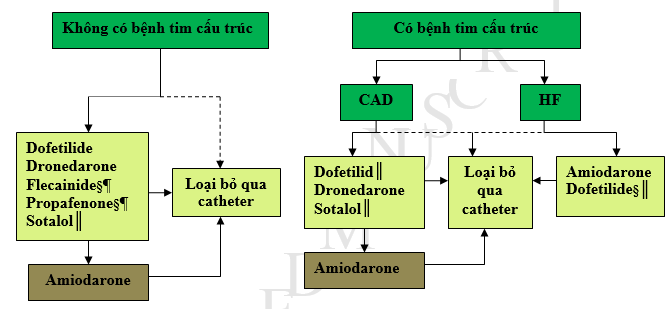

Hình 2 cho thấy một cách tiếp cận tích hợp các thuốc chống loạn nhịp và loại bỏ AF qua catheter ở bệnh nhân không bị bệnh tim và bệnh tim cấu trúc.

Hinh2.Các chiến lược cho kiểm soát nhịp ở các bệnh nhân có AF†kịch phát hoặc dai dẳng.

* Loại bỏ qua Catheter chỉ được khuyến cáo như là trị liệu hàng đầu cho các bệnh nhân AF kịch phát (khuyến cáo ClassIIa).

†Thuốc liệt kế theo alphabe.

‡Tùy theo sở thích của bệnh nhân khi thực hiện ở các trung tâm có kinh nghiệm.

§ Không được khuyến cáo với phì đại thất trái nặng (LVH)(thành dầy>1.5cm).

║Nên được sử dụng với sự chú ý ở các bệnh nhan cơ nguy cơ nhịp nhanh thất torsadesdepointes.

¶ Nên được kết hợp với các thuốc blốc nút AV.

AF: rung nhĩ;CAD: bệnh mạch vành;HF: suy tim;LVH: phì đại thất trái.

5.7. Thủ thuật ngoại khoa tạo vết sẹo trong nội tâm mạc để cản sóng loạn nhịp: Các khuyến cáo

Class IIa

1. Thủ thuật loại bỏ AF bằng ngoại khoa có thể là phù hợp cho bệnh nhân được lựa chọn với AF trải qua phẫu thuật tim cho các chỉ định khác. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class IIb

1. Thủ thuật loại bỏ AF bằng ngoại khoa có thể là phù hợp cho các bệnh nhân được lựa chọn với AF rất nhiều triệu chứng không điều chỉnh được bằng các phương pháp khác ( 169). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

6. Các nhóm bệnh nhân đặc biệt và AF

Xem Bảng 12 cho một bản tóm tắt các khuyến nghị cho phần này.

6.1. Bệnh cơ tim phì đại : Kiến nghị

Class I

1. Kháng đông được chỉ định ở bệnh nhân HCM với AF độc lập với số điểm CHA2DS2 – VASC (170, 171). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

Class IIa

1. Thuốc chống loạn nhịp có thể hữu ích để ngăn chặn AF tái phát ở bệnh nhân HCM. Amiodarone, disopyramide hoặc kết hợp với một thuốc chẹn beta hoặc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine là phương pháp điều trị hợp lý. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Loại bỏ AF qua catheter có thể có lợi cho bệnh nhân với HCM ở họ một chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp được mong muốn khi thuốc chống loạn nhịp thất bại hoặc không dung nạp (172-175). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

Class IIb

1. Sotalol, Dofetilide và dronedaron có thể được xem xét cho chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp ở những bệnh nhân HCM (13). (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

6.2. AF biến chứng của hội chứng mạch vành cấp: Các khuyến cáo

Class I

1. Chuyển nhịp khẩn cấp bằng dòng điện một chiều cơn khởi phát AF trong tình huống ACS được khuyến cáo cho các bệnh nhân có tổn thương huyết động, thiếu máu cục bộ tiếp diễn hoặc kiểm soát tần số không đầy đủ. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2 . Ức chế beta tĩnh mạch được khuyến cáo để làm chậm đáp ứng thất nhanh đối với AF ở bệnh nhân ACS không có biểu hiện HF, ổn định huyết động, hoặc co thắt phế quản. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

3. Đối với bệnh nhân ACS và AF với điểm CHA2DS2 – VASC ≥ 2, chống đông với warfarin được khuyến cáo trừ khi có chống chỉ định. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class IIb

1. Sử dụng amiodarone hoặc digoxin có thể được xem xét để làm chậm đáp ứng thất nhanh ở những bệnh nhân ACS và AF liên quan đến rối loạn chức năng thất trái nghiêm trọng và HF hoặc không ổn định huyết động. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Sử dụng chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine có thể được xem xét để làm chậm đáp ứng thất nhanh ở những bệnh nhân ACS và AF chỉ khi không có HF có ý nghĩa hoặc bất ổn huyết động. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

6.3. Cường giáp: Các khuyến cáo

Class I

1. Ức chế Beta được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát tần số thất ở bệnh nhân AF do biến chứng nhiễm độc giáp, trừ khi có chống chỉ định. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Trong những trường hợp trong đó ức chế beta không thể được sử dụng, một chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát tần số thất. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

6.4. Bệnh phổi: Các khuyến cáo

Class I

1. Thuốc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát tần thất ở bệnh nhân AF và bệnh phổi tắc nghẽn mãn tính. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Chuyển nhịp dòng một chiều có thể được nỗ lực ở bệnh nhân có bệnh phổi trở nên huyết động không ổn định như một hệ quả của khởi phát AF mới. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

6.5. Hội chứng Wolff -Parkinson-White và kích thích sớm: Các khuyến cáo

Class I

1. Chuyển nhịp dòng một chiều nhanh chóng được khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân AF, WPW và đáp ứng thất nhanh đang bị tổn thương huyết động (176 ). (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Procainamide tĩnh mạch hoặc ibutilide để khôi phục lại nhịp xoang hoặc làm chậm tần số thất được khuyến cáo cho những bệnh nhân có AF kích thích sớm và đáp ứng thất nhanh không bị tổn thương huyết động (176). (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

3. Loại bỏ đường phụ qua catheter được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân AF bị kích thích sớm có triệu chứng, đặc biệt là nếu các đường phụ có thời gian trơ ngắn cho phép dẫn truyền xuôi nhanh (176). (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class III: Tác hại

1. Sử dụng amiodarone tiêm tĩnh mạch, adenosine, digoxin (uống hoặc tiêm tĩnh mạch), hoặc thuốc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine (uống hoặc tiêm tĩnh mạch) ở những bệnh nhân bị hội chứng WPW có AF bị kích thích sớm có thể gây hại khi các phương pháp điều trị gia tăng tần số thất (177 – 179). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

6.6. Suy tim: Các khuyến cáo

Class I

1. Kiểm soát tần số tim lúc nghỉ bằng cách sử dụng hoặc ức chế beta hoặc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine được khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân AF kéo dài hoặc vĩnh viễn và HF còn bù với EF bảo tồn (HFpEF) (96). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

2. Trong trường hợp không có kích thích sớm, sử dụng tiêm tĩnh mạch ức chế beta (hoặc một chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine ở bệnh nhân có HF còn bù và EF bảo tồn) được khuyến cáo để làm chậm đáp ứng thất đối với AF trong bối cảnh cấp tính, với sự thận trọng cần thiết ở những bệnh nhân xung huyết rõ, hạ huyết áp, hoặc HF với LVEF giảm (180-183). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

3. Trong trường hợp không có kích thích sớm, digoxin tiêm tĩnh mạch hoặc amiodarone được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát nhịp tim cấp tính ở bệnh nhân suy tim (104, 181, 184, 185). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

4. Đánh giá của kiểm soát tần số tim khi gắng sức và điều chỉnh điều trị bằng thuốc để giữ tần số trong phạm vi sinh lý rất hữu ích ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng trong quá trình hoạt động. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

5 . Digoxin có hiệu quả để kiểm soát tần số tim lúc nghỉ ở bệnh nhân suy tim có EF giảm. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class IIa

1. Sự kết hợp digoxin và ức chế beta (hoặc một chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine cho bệnh nhân HF còn bù với EF bảo tồn), là phù hợp để kiểm soát tần số tim lúc nghỉ và gắng sức ở bệnh nhân AF (94, 181). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

2. Điều phù hợp để thực hiện loại bỏ nút AV với tạo nhịp tâm thất để kiểm soát nhịp tim khi điều trị thuốc không đủ hoặc không dung nạp (96, 186, 187). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

3. Amiodarone tiêm tĩnh mạch có thể hữu ích để kiểm soát tần số tim ở bệnh nhân AF khi các biện pháp khác không thành công hoặc chống chỉ định. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

4. Đối với bệnh nhân AF và đáp ứng thất nhanh gây ra hoặc bị nghi ngờ gây bệnh cơ do nhịp nhanh, điều hợp lý để đạt được kiểm soát tần số bằng hoặc blốc nút AV hoặc chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp (188-190). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

5. Đối với bệnh nhân suy tim mạn tính vẫn có triệu chứng từ AF mặc dù một chiến lược kiểm soát tần số, điều phù hợp để sử dụng một chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class IIb

1. Amiodarone uống có thể được xem xét khi tần số tim lúc nghỉ và gắng sức không thể được kiểm soát đầy đủ bằng sử dụng một ức chế beta (hoặc một chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine ở bệnh nhân HF còn bù có EF bảo tồn) hoặc digoxin, đơn thuần hoặc kết hợp. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Loại bỏ nút AV có thể được xem xét khi tần số không thể được kiểm soát và nghi ngờ bệnh cơ tim do nhịp nhanh. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class III: Tác hại

1. Loại bỏ nút AV không nên thực hiện mà không có một thử nghiệm dược lý để đạt được kiểm soát tần số thất. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

2. Để kiểm soát tần số, chất chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine tĩnh mạch, thuốc ức chế beta tiêm tĩnh mạch và dronedaron nên không được dùng cho bệnh nhân suy tim mất bù. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

6.7. AF Gia đình (di truyền): Khuyến cáo

Class IIb

1. Đối với bệnh nhân AF và các thành viên gia đình nhiều thế hệ bị AF, giới thiệu đến trung tâm chăm sóc y tế chuyên ngành để được tư vấn di truyền và làm test có thể được xem xét. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

6.8. Sau phẫu thuật tim và lồng ngực: Các khuyến cáo

Class I

1. Điều trị bệnh nhân phát triển AF sau khi phẫu thuật tim bằng ức chế beta được khuyến cáo trừ khi có chống chỉ định (191-194). (Mức độ bằng chứng: A)

2. Một chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine được khuyến cáo khi ức chế beta là không đủ để đạt được kiểm soát tần số ở bệnh nhân AF sau phẫu thuật (195). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

Class IIa

1. Sử dụng amiodarone trước phẫu thuật làm giảm tỷ lệ AF ở những bệnh nhân trải qua phẫu thuật tim và là phù hợp trong điều trị dự phòng cho bệnh nhân có nguy cơ cao AF sau phẫu thuật ( 196-198 ). ( Mức độ bằng chứng: A)

2. Điều phù hợp để khôi phục lại nhịp xoang bằng thuốc với ibutilide hoặc chuyển nhịp bằng dòng một chiều ở những bệnh nhân phát triển AF sau phẫu thuật, như tư vấn cho các bệnh nhân không phẫu thuật (199). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

3. Điều phù hợp để sử dụng các thuốc chống loạn nhịp trong nỗ lực để duy trì nhịp xoang ở những bệnh nhân AF tái phát hoặc trơ sau phẫu thuật, như tư vấn cho các bệnh nhân phát triển AF khác (195). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

4. Điều phù hợp để sử dụng các thuốc chống huyết khối ở những bệnh nhân phát triển AF sau phẫu thuật, như tư vấn cho các bệnh nhân không phẫu thuật (200). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

5. Điều phù hợp để điều chỉnh AF sau phẫu thuật khởi phát mới, dung nạp tốt với kiểm soát tần số và kháng đông bằng chuyển nhịp nếu AF không tự chuyển về nhịp xoang trong quá trình theo dõi. (Mức độ bằng chứng: C)

Class IIb

1. Sử dụng sotalol để dự phòng có thể được xem xét cho những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ phát triển AF sau phẫu thuật tim ( 194, 201). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

2. Sử dụng colchicine có thể được xem xét cho bệnh nhân sau phẫu thuật để giảm AF sau phẫu thuật tim (202). (Mức độ bằng chứng: B)

Bảng12.Tóm tắt các khuyến cáo cho các nhóm bệnh nhân chuyên biệt và AF

|

Các khuyến cáo |

COR |

LOE |

Tham khảo |

|

Bệnh cơ tim phì đại (HCM) |

|||

|

Kháng đông được chỉ định ở bệnh nhân HCM có AFđộc lập với điểm CHA2DS2-VASc |

I |

B |

(170,171) |

|

Các thuốc chống loạn nhịp có thể hữu ích để ngăn chặn AF tái phát trong HCM.Amiodarone hoặcdisopyramide phối hợp với ức chế beta hoặc chẹn kệnh canxi là phù hợp |

IIa |

C |

N/A |

|

Loại bỏ AFqua catheter có thể có lợi ích cho HCMđể làm dễ dàng cho chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp khi các chống loạn nhịp thất bại hoặc không dung nạp |

IIa |

B |

(172-175) |

|

Sotalol,dofetilidevàdronedarone có thể được xem xét cho chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp ởHCM |

IIb |

C |

(13) |

|

AF biến chứng của ACS |

|||

|

Chuyển nhịp khẩn trương cơn khởi phát AF mới trong tình huốngACS được khuyến cáo ở các bệnh nhân tổn thương huyết động, tiếp tục thiếu máu cục bộ, hoặc kiểm soát tần số không đầy đủ. |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Ức chế beta tĩnh mạch được khuyến cáo để làm chậm RVR trong ACSvà khôngHF,không ổn định huyết động hoặc co thất phế quản |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Với ACSvàAFcó điểm CHA2DS2-VASc(điểm≥2),kháng đông bằng warfarin được khuyến cáo ngoại trừ chống chỉ định. |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Amiodaronehoặcdigoxin có thể được xem xét để làm chậm RVRtrong ACSvà AF,rối loạn chức năng LV nặng và HFhoặc không ổn định huyết động. |

IIb |

C |

N/A |

|

Các thuốc chẹn kệnh canxi Nondihydropyridinecó thể được xem xét để làm chậm RVRtrongACSvàAFchỉ khi không có HF đáng kể hoặc không ổn định huyết động. |

IIb |

C |

N/A |

|

Cường giáp |

|||

|

Ức chế beta được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát tần số thất trong AF biến chứng nhiễm độc giáp, ngoại trừ chống chỉ định. |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Các thuốc chẹn kênh canxi Nondihydropyridine để kiểm soát tần số thất với AFvà nhiễm độc giáp khi ức chếbeta không thể sử dụng. |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Bệnh phổi |

|||

|

Các thuốc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát tần số thất trong COPDvàAF |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Chuyển nhịp cần được nỗ lực ở bệnh nhân bệnh phổi trở nên không không ổn định huyết động có cơn khởi phát AF |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Hội chứng WPWvà kích thích sớm |

|||

|

Chuyển nhịp được khuyến cáo với AF,WPW vàRVRở người có tổn thương huyết động. |

I |

C |

(176) |

|

Tiêm tĩnh mạch (IV)procainamide hoặc ibutilide để phục hồi nhịp xoang hoặc làm chậm tần số thất được khuyến cáo với AF kích thích sớm vàRVRở người không có tổn thương huyết động. |

I |

C |

(176) |

|

Loại bỏ đường phụ qua catheter được khuyến cáo ở các bệnh nhân có triệu chứng với AF kích thích sớm,đặc biệt nếu đường phụ có thời gian trơ ngắn. |

I |

C |

(176) |

|

Tiêm tĩnh mạch (IV)amiodarone,adenosine,digoxin,hoặc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine WPW người có AF kích thích sớm có khả năng gây hại |

III: Có hại |

B |

(177-179) |

|

Suy tim |

|||

|

Ức chế betahoặc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridineđược khuyến cáo cho AF dai dẳng hoặc vĩnh viễn ở bệnh nhân có HFpEF. |

I |

B |

(96) |

|

Khi không có kích thích sớm, tiêm tĩnh mạch ức chế beta (hoặc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine vớiHFpEF)được khuyến cáo để làm chậm đáp ứng thất đối với AF trong tình huống cấp tính,,ethực hiện thận trọng ở bệnh nhân xung huyết rõ hoặc hạ huyết áp. |

I |

B |

(180-183) |

|

Suy tim có chức năng thất trái bảo tồn (HFrEF) |

|

|

|

|

Khi không có kích thích sớm,tiêm tĩnh mạch digoxinhoặcamiodarone được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát tần số tim cấp thời. |

I |

B |

(104,181,184, 185) |

|

Đánh giá tần số tim trong quá trình gắng sức và điều chỉnh điều trị thuốc ở các bệnh nhân có triệu chứng trong quá trình hoạt động. |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Digoxin có hiệu quả để kiểm soát tần số tim lúc nghỉ với HFrEF |

I |

C |

N/A |

|

Phối hợp digoxinvà ức chếbeta(hoặc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridinevớiHFpEF) là phù hợp để kiểm soát tần số tim lúc nghỉ và gắng sức với AF. |

IIa |

B |

(94,181) |

|

Phù hợp để thực hiện loại bỏ nút AV với tạo nhịp thất để kiểm soát tần số tim khi điều trị thuốc không đầy đủ hoặc không dung nạp. |

IIa |

B |

(96,186,187) |

|

Tiêm tĩnh mạch amiodarone có thể hữu ích để kiểm soát tần số tim với AF khi các phương pháp khác thất bại hoặc chống chỉ định. |

IIa |

C |

N/A |

|

Với AFvàRVR,do bệnh cơ tim do nhịp nhanh gây ra hoặc nghi ngờ, điều phù hợp để đạt kiểm soát tần số bằng blốc nút AV hoặc chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp. |

IIa |

B |

(188-190) |

|

Ở các bệnh nhân HF mạn tính còn có triệu chứng do AF mặc dù chiến lược kiểm soát tần số, điều phù hợp để sử dụng chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp. |

IIa |

C |

N/A |

|

Amiodarone có thể được xem xét khi tần số tim lúc nghỉ hoặc gắng sức không thể được kiểm soát bằng ức chế beta(hoặc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine vớiHFpEF)hoặcdigoxin, đơn độc hoặc kết hợp. |

IIb |

C |

N/A |

|

Loại bỏ nút AVcó thẻ được xem xét khi tần số không thể kiểm soát và nghi ngờ bệnh cơ tim do nhịp nhanh. |

IIb |

C |

N/A |

|

Loại bỏ nút AV không nên thực hiện khi không trải nghiệm bằng thuốc để kiểm soát tần số thất. |

III: Có hại |

C |

N/A |

|

Đối với kiểm soát tần số, tiêm tĩnh mạch chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine, ức chế betavà dronedaronekhông nên cho với HF mất bù. |

III: Có hại

|

C |

N/A |

|

AF gia đình (di truyền) |

|||

|

Với AF và các thành viên gia đình nhiều thế hệ AF, chuyển đến trung tâm chăm sóc chuyên ngành để tư vấn và thử test có thể được xem xét |

IIb |

C |

N/A |

|

AF sau ngoại khoa tim và lồng ngực |

|||

|

Ức chế betađược khuyến cáo để điều trị AF sau phẫu thuật ngoại trừ có chống chỉ định |

I |

A |

(191-194) |

|

Chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine được khuyến cáo khi ức chế beta không phù hợp để đạt kiểm soát tần số với AF sau mổ. |

I |

B |

(195) |

|

Amiodarone sau làm giảm AF với ngoại khoa tim và phù hợp như là điều trị dự phòng cho nguy cơ cao AF sau mổ. |

IIa |

A |

(196-198) |

|

Điều phù hợp để phục hồi nhịp xoang bằng thuốc vớiibutilidehoặc chuyển nhịp bằng dòng một chiều với AF sau mổ. |

IIa |

B |

(199) |

|

Điều phù hợp để sử dụng thuốc chống huyết khối để duy trì nhịp xoang với AF tái phát hoặc AF trơ sau mổ. |

IIa |

B |

(195) |

|

Điều phù hợp cho sử dụng thuốc chống huyết khối cho AF sau mổ. |

IIa |

B |

(200) |

|

Điều phù hợp để điều trị AF khởi phát mới sau phẫu thuật với kiểm soát tần số và kháng đông với chuyển nhịp nếu AF không tự phục hồi về nhịp xoang trong quá trình theo dõi. |

IIa |

C |

N/A |

|

Sotalol dự phòng có thể được xem xét ở các bệnh nhân có nguy cơ AF sau ngoại khoa tim. |

IIb |

B |

(194,201) |

|

Colchicinecó thể được xem xét sau phẫu thuật để giảm AF sau ngoại khoa tim. |

IIb |

B |

(202) |

AF: rung nhĩ ; AV: nhĩ thất; COPD: bệnh phổi tắc nghẽn mãn tính; COR: phân loại khuyến cáo; HCM: bệnh cơ tim phì đại; HF: suy tim ; HFpE: suy tim với phân suất tống máu bảo tồn; HfrEF: suy tim với phân suất tống máu giảm; IV, tiêm tĩnh mạch; LOE: mức độ chứng cứ; LV: thất trái ; N / A: không áp dụng; RVR: đáp ứng thất nhanh; và WPW: Wolff -Parkinson-White .

7. Các khoảng trống bằng chứng và các hướng nghiên cứu trong tương lai

Thập kỷ qua đã chứng kiến sự tiến bộ đáng kể trong sự hiểu biết về cơ chế AF, thực hiện loại bỏ trên lâm sàng để duy trì nhịp xoang và các loại thuốc mới để phòng ngừa đột quỵ. Tiếp tục nghiên cứu là cần thiết để thông tin tốt hơn cho bác sĩ lâm sàng như các nguy cơ và lợi ích của lựa chọn điều trị cho mỗi bệnh nhân. Nghiên cứu tiếp tục là cần thiết đi vào các cơ chế khởi đầu và duy trì AF. Sự hiểu biết tốt hơn về các cơ chế mô và tế bào sẽ, hy vọng, dẫn đến nhiều cách tiếp cận xác định để điều trị và bãi bỏ AF. Điều này bao gồm cách tiếp cận mới về phương pháp luận cho loại bỏ AF sẽ ảnh hưởng thuận lợi đến sự sống còn, thuyên tắc huyết khối và chất lượng cuộc sống trên bệnh sử bệnh nhân khác nhau. Liệu pháp dược lý mới là cần thiết, bao gồm cả thuốc chống loạn nhịp có chọn lọc nhĩ và các loại thuốc nhắm mục tiêu xơ hóa, hy vọng sẽ đạt được đánh giá lâm sàng. Bước đầu thành công của các thuốc chống đông máu mới là đáng khích lệ, khảo sát tiếp theo sẽ thông tin tốt hơn cho thực hành lâm sàng để tối ưu hóa các ứng dụng mang lại lợi ích và giảm thiểu nguy cơ của các thuốc, đặc biệt ở người cao tuổi có các bệnh đi kèm và thời kỳ quanh các thủ thuật. Khảo sát tiếp theo phải được thực hiện để hiểu rõ hơn mối liên hệ giữa sự hiện diện của AF, gánh nặng AF và nguy cơ đột quỵ và cũng để xác định rõ hơn mối quan hệ giữa AF và chứng mất trí. Vai trò của các trị liệu thủ thuật và ngoại khoa mới nổi để làm giảm đột quỵ sẽ được xác định. Hứa hẹn tuyệt với nằm ở dự phòng. Các chiến lược tương lai cho việc đảo ngược sự phát triển dịch tễ của AF sẽ tim thấy từ khoa học cơ bản và di truyền, dịch tễ học và nghiên cứu lâm sàng .

Tài liệu tham khảo

1. ACCF.AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Methodology Manual and Policies From the ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association, Inc. Cardiosource.com. 2010. Available at:

http://assets.cardiosource.com/Methodology_Manual_for_ACC_AHA_Writing_Com-mittee.pdf.

http://my.americanheart.org/idc/groups/ahamahpublic/@wcm/@sop/documents/down-loadable/ucm_319826.pdf.

Accessed May 16, 2012.

2. Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research, Institute of Medicine. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

3. Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines; Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

4. January C, Wann L, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. JACC. 2014;

5. Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on dabigatran): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1330-7.

6. Wann LS, Curtis AB, January CT, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (Updating the 2006 Guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:223-42.

7. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257-e354.

8. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:e101-e198.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Research Protocol: Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?productid=946&pageaction=displayproduct. 2012; Accessed December 2012.

10. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-52.

11. Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:e50-103.

12. Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e123-e210.

13. Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e212-e260.

14. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44-122.

15. Smith SC, Jr., Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American

16. elines for the management of atrial fibrillation * Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012.

17. Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e6-e75.

18. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:e44-e164.

19. Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Spencer FA, et al. Antiplatelet drugs: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e89S-119S.

20. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-e239.

21. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e78-e140.

22. Amsterdam E, Wenger NK, Brindis R, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in Collaboration With the American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. In Press. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014; In Press

23. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014.

24. Goff DC, Jr., Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013.

25. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC Guideline on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013.

26. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013.

27. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013.

28. Furie KL, Goldstein LB, Albers GW, et al. Oral antithrombotic agents for the prevention of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a science advisory for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43:3442-53.

29. Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: a report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); and in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the

Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:632-96.

30. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369-429.

31. Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:120-9.

32. Santini M, Gasparini M, Landolina M, et al. Device-detected atrial tachyarrhythmias predict adverse outcome in real-world patients with implantable biventricular defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:167-72.

33. Savelieva I, Kakouros N, Kourliouros A, et al. Upstream therapies for management of atrial fibrillation: review of clinical evidence and implications for European Society of Cardiology guidelines. Part I: primary prevention. Europace. 2011;13:308-28.

34. Wakili R, Voigt N, Kaab S, et al. Recent advances in the molecular pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2955-68.

35. Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, et al. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840-4.

36. Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:2920-5.

37. Frost L, Hune LJ, Vestergaard P. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. Am J Med. 2005;118:489-95.

38. Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, et al. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2004;292:2471-7.

39. Gami AS, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:565-71.

40. Mathew JP, Fontes ML, Tudor IC, et al. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2004;291:1720-9.

41. Heeringa J, Kors JA, Hofman A, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam Study. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1163-9.

42. Aizer A, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, et al. Relation of vigorous exercise to risk of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1572-7.

43. Mont L, Sambola A, Brugada J, et al. Long-lasting sport practice and lone atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:477-82.

44. Frost L, Frost P, Vestergaard P. Work related physical activity and risk of a hospital discharge diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:49-53.

45. Conen D, Tedrow UB, Cook NR, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. JAMA. 2008;300:2489-96.

46. Frost L, Vestergaard P. Alcohol and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: a cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1993-8.

47. Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:427-36.

48. Sawin CT, Geller A, Wolf PA, et al. Low serum thyrotropin concentrations as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in older persons. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1249-52.

49. Cappola AR, Fried LP, Arnold AM, et al. Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295:1033-41.

50. Frost L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Hyperthyroidism and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1675-8.

51. Mitchell GF, Vasan RS, Keyes MJ, et al. Pulse pressure and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2007;297:709-15.

52. Marcus GM, Alonso A, Peralta CA, et al. European ancestry as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in African Americans. Circulation. 2010;122:2009-15.

53. Lubitz SA, Yin X, Fontes JD, et al. Association between familial atrial fibrillation and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2010;304:2263-9.

54. Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Albert CM, et al. Meta-analysis identifies six new susceptibility loci for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2012;44:670-5.

55. Gudbjartsson DF, Holm H, Gretarsdottir S, et al. A sequence variant in ZFHX3 on 16q22 associates with atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke. Nat Genet. 2009;41:876-8.

56. Gudbjartsson DF, Arnar DO, Helgadottir A, et al. Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature. 2007;448:353-7.

57.

Benjamin EJ, Rice KM, Arking DE, et al. Variants in ZFHX3 are associated with atrial fibrillation in individuals of European ancestry. Nat Genet. 2009;41:879-81.

58. Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population-based estimates. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:2N-9N.

59. Pritchett AM, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, et al. Left atrial volume as an index of left atrial size: a population- based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1036-43.

60. Cao JJ, Thach C, Manolio TA, et al. C-reactive protein, carotid intima-media thickness, and incidence of ischemic stroke in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2003;108:166-70.

61. Aviles RJ, Martin DO, Apperson-Hansen C, et al. Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:3006-10.

62. Patton KK, Ellinor PT, Heckbert SR, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is a major predictor of the development of atrial fibrillation: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2009;120:1768-74.

63. Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:655-63.

64. Ahmad Y, Lip GY, Apostolakis S. New oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: impact of gender, heart failure, diabetes mellitus and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10:1471-80.

65. Chiang CE, Naditch-Brule L, Murin J, et al. Distribution and risk profile of paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation in routine clinical practice: insight from the real-life global survey evaluating patients with atrial fibrillation international registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:632-9.

66. Flaker G, Ezekowitz M, Yusuf S, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared to warfarin in patients with paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation: results from the RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:854-5.

67. Hohnloser S.H., Duray G.Z., Baber U., et al. Prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: current strategies and future directions. Eur Heart J. 2007;10:H4-H10.

68. Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263-72.

69. Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, Hansen ML, et al. The value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for refining stroke risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score 0-1: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:1172-9.

70. Mason PK, Lake DE, DiMarco JP, et al. Impact of the CHA2DS2-VASc score on anticoagulation recommendations for atrial fibrillation. Am J Med. 2012;125:603-6.

71. Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Wintzen AR, et al. Optimal oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:11-7.

72. Acar J, Iung B, Boissel JP, et al. AREVA: multicenter randomized comparison of low-dose versus standard-dose anticoagulation in patients with mechanical prosthetic heart valves. Circulation. 1996;94:2107-12.

73. Hering D, Piper C, Bergemann R, et al. Thromboembolic and bleeding complications following St. Jude Medical valve replacement: results of the German Experience With Low-Intensity Anticoagulation Study. Chest. 2005;127:53-9.

74. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-51.

75. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-91.

76. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981-92.

77. Matchar DB, Jacobson A, Dolor R, et al. Effect of home testing of international normalized ratio on clinical events. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1608-20.

78. Ezekowitz MD, James KE, Radford MJ, et al. Initiating and Maintaining Patients on Warfarin Anticoagulation: The Importance of Monitoring. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 1999;4:3-8.

79. Hirsh J, Fuster V. Guide to anticoagulant therapy. Part 2: Oral anticoagulants. American Heart Association. Circulation. 1994;89:1469-80.

80. Aguilar M, Hart R. Antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD001925.

81. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857-67.

82. Winkelmayer WC, Liu J, Setoguchi S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of warfarin initiation in older hemodialysis patients with incident atrial fibrillation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2662-8.

83.

Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1107-15.

84. Hariharan S, Madabushi R. Clinical pharmacology basis of deriving dosing recommendations for dabigatran in patients with severe renal impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:119S-25S.

85. Lehr T, Haertter S, Liesenfeld KH, et al. Dabigatran etexilate in atrial fibrillation patients with severe renal impairment: dose identification using pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:1373- 8.

86. Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, et al. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:806-17.

87. Van de Werf F, Brueckmann M, Connolly SJ, et al. A comparison of dabigatran etexilate with warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves: THE Randomized, phase II study to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of oral dabigatran etexilate in patients after heart valve replacement (RE-ALIGN). Am Heart J. 2012;163:931-7.

88. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1449-57.

89. Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864-70.

90. Lip GY, Tse HF, Lane DA. Atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 2012;379:648-61.

91. Lane DA, Lip GY. Use of the CHA(2)DS(2)-VASc and HAS-BLED scores to aid decision making for thromboprophylaxis in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;126:860-5.

92. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Asinger RW, et al. Warfarin in atrial fibrillation patients with moderate chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2599-604.

93. Farshi R, Kistner D, Sarma JS, et al. Ventricular rate control in chronic atrial fibrillation during daily activity and programmed exercise: a crossover open-label study of five drug regimens. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:304-10.

94. Steinberg JS, Katz RJ, Bren GB, et al. Efficacy of oral diltiazem to control ventricular response in chronic atrial fibrillation at rest and during exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9:405-11.

95. Olshansky B, Rosenfeld LE, Warner AL, et al. The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study: approaches to control rate in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1201-8.

96. Abrams J, Allen J, Allin D, et al. Efficacy and safety of esmolol vs propranolol in the treatment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias: a multicenter double-blind clinical trial. Am Heart J. 1985;110:913-22.

97. Ellenbogen KA, Dias VC, Plumb VJ, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of continuous intravenous diltiazem infusion for 24-hour heart rate control during atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:891-7.

98. Siu CW, Lau CP, Lee WL, et al. Intravenous diltiazem is superior to intravenous amiodarone or digoxin for achieving ventricular rate control in patients with acute uncomplicated atrial fibrillation. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2174-9.

99. Platia EV, Michelson EL, Porterfield JK, et al. Esmolol versus verapamil in the acute treatment of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:925-9.

100. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363-73.

101. Delle KG, Geppert A, Neunteufl T, et al. Amiodarone versus diltiazem for rate control in critically ill patients with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1149-53.

102. Hou ZY, Chang MS, Chen CY, et al. Acute treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter with a tailored dosing regimen of intravenous amiodarone. A randomized, digoxin-controlled study. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:521-8.

103. Clemo HF, Wood MA, Gilligan DM, et al. Intravenous amiodarone for acute heart rate control in the critically ill patient with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:594-8.

104. Ozcan C, Jahangir A, Friedman PA, et al. Long-term survival after ablation of the atrioventricular node and implantation of a permanent pacemaker in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1043-51.

105. Weerasooriya R, Davis M, Powell A, et al. The Australian Intervention Randomized Control of Rate in Atrial Fibrillation Trial (AIRCRAFT). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1697-702.

106. Wood MA, Brown-Mahoney C, Kay GN, et al. Clinical outcomes after ablation and pacing therapy for atrial fibrillation : a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2000;101:1138-44.

107. Gulamhusein S, Ko P, Carruthers SG, et al. Acceleration of the ventricular response during atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome after verapamil. Circulation. 1982;65:348-54.

108. Connolly SJ, Camm AJ, Halperin JL, et al. Dronedarone in high-risk permanent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2268-76.

109. Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, McMurray JJ, et al. Increased mortality after dronedarone therapy for severe heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2678-87.

110.

Moreyra E, Finkelhor RS, Cebul RD. Limitations of transesophageal echocardiography in the risk assessment of patients before nonanticoagulated cardioversion from atrial fibrillation and flutter: an analysis of pooled trials. Am Heart J. 1995;129:71-5.

111. Gallagher MM, Hennessy BJ, Edvardsson N, et al. Embolic complications of direct current cardioversion of atrial arrhythmias: association with low intensity of anticoagulation at the time of cardioversion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:926-33.

112. Jaber WA, Prior DL, Thamilarasan M, et al. Efficacy of anticoagulation in resolving left atrial and left atrial appendage thrombi: A transesophageal echocardiographic study. Am Heart J. 2000;140:150-6.

113. You JJ, Singer DE, Howard PA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e531S-e575S.

114. Klein AL, Grimm RA, Murray RD, et al. Use of transesophageal echocardiography to guide cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1411-20.

115. Nagarakanti R, Ezekowitz MD, Oldgren J, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation. 2011;123:131-6.

116. Piccini JP, Stevens SR, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Outcomes Following Cardioversion and Atrial Fibrillation Ablation in Patients Treated with Rivaroxaban and Warfarin in the ROCKET AF Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1998- 2006.

117. Flaker G, Lopes RD, Al-Khatib SM, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Apixaban in Patients Following Cardioversion for Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013.

118. von BK, Mills AM. Is discharge to home after emergency department cardioversion safe for the treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation? Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:517-20.

119. Oral H, Souza JJ, Michaud GF, et al. Facilitating transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation with ibutilide pretreatment. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1849-54.

120. Alboni P, Botto GL, Baldi N, et al. Outpatient treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation with the “pill-in-the- pocket” approach. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2384-91.

121. Ellenbogen KA, Clemo HF, Stambler BS, et al. Efficacy of ibutilide for termination of atrial fibrillation and flutter. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:42-5.

122. Khan IA. Single oral loading dose of propafenone for pharmacological cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:542-7.

123. Patsilinakos S, Christou A, Kafkas N, et al. Effect of high doses of magnesium on converting ibutilide to a safe and more effective agent. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:673-6.

124. Singh S, Zoble RG, Yellen L, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral dofetilide in converting to and maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter: the symptomatic atrial fibrillation investigative research on dofetilide (SAFIRE-D) study. Circulation. 2000;102:2385-90.

125. Stambler BS, Wood MA, Ellenbogen KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of repeated intravenous doses of ibutilide for rapid conversion of atrial flutter or fibrillation. Ibutilide Repeat Dose Study Investigators. Circulation. 1996;94:1613-21.

126. Khan IA, Mehta NJ, Gowda RM. Amiodarone for pharmacological cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2003;89:239-48.

127. Letelier LM, Udol K, Ena J, et al. Effectiveness of amiodarone for conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:777-85.

128. Pedersen OD, Bagger H, Keller N, et al. Efficacy of dofetilide in the treatment of atrial fibrillation-flutter in patients with reduced left ventricular function: a Danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide (diamond) substudy. Circulation. 2001;104:292-6.

129. Singh BN, Singh SN, Reda DJ, et al. Amiodarone versus sotalol for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1861-72.

130. Lafuente-Lafuente C, Mouly S, Longas-Tejero MA, et al. Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD005049.

131. Channer KS, Birchall A, Steeds RP, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of pre-treatment and short- or long-term maintenance therapy with amiodarone supporting DC cardioversion for persistent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:144-50.

132. Galperin J, Elizari MV, Chiale PA, et al. Efficacy of amiodarone for the termination of chronic atrial fibrillation and maintenance of normal sinus rhythm: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled, double blind trial. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2001;6:341-50.

133. Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van EM, et al. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:668-78.

134.

Singh BN, Connolly SJ, Crijns HJ, et al. Dronedarone for maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation or flutter. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:987-99.

135. Touboul P, Brugada J, Capucci A, et al. Dronedarone for prevention of atrial fibrillation: a dose-ranging study. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1481-7.

136. Van Gelder IC, Crijns HJ, Van Gilst WH, et al. Efficacy and safety of flecainide acetate in the maintenance of sinus rhythm after electrical cardioversion of chronic atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:1317-21.

137. Roy D, Talajic M, Dorian P, et al. Amiodarone to prevent recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Canadian Trial of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:913-20.

138. Bellandi F, Simonetti I, Leoncini M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of propafenone and sotalol for the maintenance of sinus rhythm after conversion of recurrent symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:640-5.

139. Dogan A, Ergene O, Nazli C, et al. Efficacy of propafenone for maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with recent onset or persistent atrial fibrillation after conversion: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Acta Cardiol. 2004;59:255-61.

140. Pritchett EL, Page RL, Carlson M, et al. Efficacy and safety of sustained-release propafenone (propafenone SR) for patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:941-6.

141. Benditt DG, Williams JH, Jin J, et al. Maintenance of sinus rhythm with oral d,l-sotalol therapy in patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation and/or atrial flutter. d,l-Sotalol Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:270-7.

142. Freemantle N, Lafuente-Lafuente C, Mitchell S, et al. Mixed treatment comparison of dronedarone, amiodarone, sotalol, flecainide, and propafenone, for the management of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2011;13:329-45.

143. Piccini JP, Hasselblad V, Peterson ED, et al. Comparative efficacy of dronedarone and amiodarone for the maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1089-95.

144. Le Heuzey JY, De Ferrari GM, Radzik D, et al. A short-term, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dronedarone versus amiodarone in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: the DIONYSOS study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:597-605.

145. Maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: an AFFIRM substudy of the first antiarrhythmic drug. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:20-9.

146. Brunton L. Antiarrhythmic drugs. In: Laso JS, Parker KL, editors. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012:899-932.

147. Healey JS, Baranchuk A, Crystal E, et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1832-9.

148. Schneider MP, Hua TA, Bohm M, et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation by Renin-Angiotensin system inhibition a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2299-307.

149. Ducharme A, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA, et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation in patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure by candesartan in the Candesartan in Heart failure: assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Am Heart J. 2006;151:985-91.

150. Jibrini MB, Molnar J, Arora RR. Prevention of atrial fibrillation by way of abrogation of the renin-angiotensin system: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2008;15:36-43.

151. Liakopoulos OJ, Choi YH, Kuhn EW, et al. Statins for prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a systematic literature review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:678-86.

152. Patti G, Chello M, Candura D, et al. Randomized trial of atorvastatin for reduction of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: results of the ARMYDA-3 (Atorvastatin for Reduction of MYocardial Dysrhythmia After cardiac surgery) study. Circulation. 2006;114:1455-61.

153. Goette A, Schon N, Kirchhof P, et al. Angiotensin II-antagonist in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (ANTIPAF) trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:43-51.

154. Calkins H, Reynolds MR, Spector P, et al. Treatment of atrial fibrillation with antiarrhythmic drugs or radiofrequency ablation: two systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:349-61.

155. Bonanno C, Paccanaro M, La VL, et al. Efficacy and safety of catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010;11:408-18.

156. Nair GM, Nery PB, Diwakaramenon S, et al. A systematic review of randomized trials comparing radiofrequency ablation with antiarrhythmic medications in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:138-44.

157. Parkash R, Tang AS, Sapp JL, et al. Approach to the catheter ablation technique of paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:729- 38.

158.

Piccini JP, Lopes RD, Kong MH, et al. Pulmonary vein isolation for the maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:626- 33.

159. Jais P, Cauchemez B, Macle L, et al. Catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial fibrillation: the A4 study. Circulation. 2008;118:2498-505.

160. Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, et al. Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:333-40.

161. Stabile G, Bertaglia E, Senatore G, et al. Catheter ablation treatment in patients with drug-refractory atrial fibrillation: a prospective, multi-centre, randomized, controlled study (Catheter Ablation For The Cure Of Atrial Fibrillation Study). Eur Heart J. 2006;27:216-21.

162. Oral H, Pappone C, Chugh A, et al. Circumferential pulmonary-vein ablation for chronic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:934-41.

163. Mont L, Bisbal F, Hernandez-Madrid A, et al. Catheter ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drug treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation: a multicentre, randomized, controlled trial (SARA study). Eur Heart J. 2013.

164. Wazni OM, Marrouche NF, Martin DO, et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first-line treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2634-40.

165. Morillo C, Verma A, Kuck K, et al. Radiofrequency Ablation vs Antiarrhythmic Drugs as First-Line Treatment of Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation: (RAAFT 2): A randomized trial. (IN PRESS). JAMA. 2014.

166. Cosedis NJ, Johannessen A, Raatikainen P, et al. Radiofrequency ablation as initial therapy in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1587-95.

167. Haissaguerre M, Hocini M, Sanders P, et al. Catheter ablation of long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation: clinical outcome and mechanisms of subsequent arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1138-47.

168. Boersma LV, Castella M, van BW, et al. Atrial fibrillation catheter ablation versus surgical ablation treatment (FAST): a 2-center randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2012;125:23-30.

169. Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Bellone P, et al. Clinical profile of stroke in 900 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:301-7.

170. Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Casey SA, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the clinical course of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;104:2517-24.

171. Bunch TJ, Munger TM, Friedman PA, et al. Substrate and procedural predictors of outcomes after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1009-14.

172. Di DP, Olivotto I, Delcre SD, et al. Efficacy of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: impact of age, atrial remodelling, and disease progression. Europace. 2010;12:347-55.

173. Gaita F, Di DP, Olivotto I, et al. Usefulness and safety of transcatheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1575-81.

174. Kilicaslan F, Verma A, Saad E, et al. Efficacy of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:275-80.

175. Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias–executive summary. a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the European society of cardiology committee for practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493-531.

176. Boriani G, Biffi M, Frabetti L, et al. Ventricular fibrillation after intravenous amiodarone in Wolff-Parkinson- White syndrome with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1996;131:1214-6.

177. Kim RJ, Gerling BR, Kono AT, et al. Precipitation of ventricular fibrillation by intravenous diltiazem and metoprolol in a young patient with occult Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:776-9.

178. Simonian SM, Lotfipour S, Wall C, et al. Challenging the superiority of amiodarone for rate control in Wolff- Parkinson-White and atrial fibrillation. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:421-6.

179. Balser JR, Martinez EA, Winters BD, et al. Beta-adrenergic blockade accelerates conversion of postoperative supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1052-9.

180. Tamariz LJ, Bass EB. Pharmacological rate control of atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Clin. 2004;22:35-45.

181. Lewis RV, McMurray J, McDevitt DG. Effects of atenolol, verapamil, and xamoterol on heart rate and exercise tolerance in digitalised patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1989;13:1-6.

182. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1-e90.

183.

Roberts SA, Diaz C, Nolan PE, et al. Effectiveness and costs of digoxin treatment for atrial fibrillation and flutter. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:567-73.

184. Segal JB, McNamara RL, Miller MR, et al. The evidence regarding the drugs used for ventricular rate control. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:47-59.

185. Feld GK, Fleck RP, Fujimura O, et al. Control of rapid ventricular response by radiofrequency catheter modification of the atrioventricular node in patients with medically refractory atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1994;90:2299-307.

186. Williamson BD, Man KC, Daoud E, et al. Radiofrequency catheter modification of atrioventricular conduction to control the ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:910-7.

187. Khan MN, Jais P, Cummings J, et al. Pulmonary-vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1778-85.

188. Nerheim P, Birger-Botkin S, Piracha L, et al. Heart failure and sudden death in patients with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy and recurrent tachycardia. Circulation. 2004;110:247-52.

189. Gentlesk PJ, Sauer WH, Gerstenfeld EP, et al. Reversal of left ventricular dysfunction following ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:9-14.

190. Crystal E, Garfinkle MS, Connolly SS, et al. Interventions for preventing post-operative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD003611.

191. Yoshioka I, Sakurai M, Namai A, et al. Postoperative treatment of carvedilol following low dose landiolol has preventive effect for atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:464- 7.

192. Davis EM, Packard KA, Hilleman DE. Pharmacologic prophylaxis of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: beyond beta-blockers. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:749, 274e-749, 318e.

193. Koniari I, Apostolakis E, Rogkakou C, et al. Pharmacologic prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:121.

194. Hilleman DE, Hunter CB, Mohiuddin SM, et al. Pharmacological management of atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2005;5:361-9.

195. Daoud EG, Strickberger SA, Man KC, et al. Preoperative amiodarone as prophylaxis against atrial fibrillation after heart surgery. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1785-91.

196. Guarnieri T, Nolan S, Gottlieb SO, et al. Intravenous amiodarone for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after open heart surgery: the Amiodarone Reduction in Coronary Heart (ARCH) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:343-7.

197. Mitchell LB, Exner DV, Wyse DG, et al. Prophylactic Oral Amiodarone for the Prevention of Arrhythmias that Begin Early After Revascularization, Valve Replacement, or Repair: PAPABEAR: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:3093-100.

198. VanderLugt JT, Mattioni T, Denker S, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibutilide fumarate for the conversion of atrial arrhythmias after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:369-75.

199. Al-Khatib SM, Hafley G, Harrington RA, et al. Patterns of management of atrial fibrillation complicating coronary artery bypass grafting: Results from the PRoject of Ex-vivo Vein graft ENgineering via Transfection IV (PREVENT-IV) Trial. Am Heart J. 2009;158:792-8.

200. Shepherd J, Jones J, Frampton GK, et al. Intravenous magnesium sulphate and sotalol for prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12:iii-95.

201. Imazio M, Brucato A, Ferrazzi P, et al. Colchicine reduces postoperative atrial fibrillation: results of the Colchicine for the Prevention of the Postpericardiotomy Syndrome (COPPS) atrial fibrillation substudy. Circulation. 2011;124:2290-5.