TS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

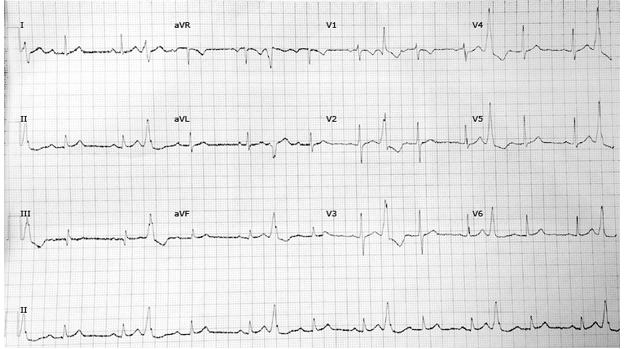

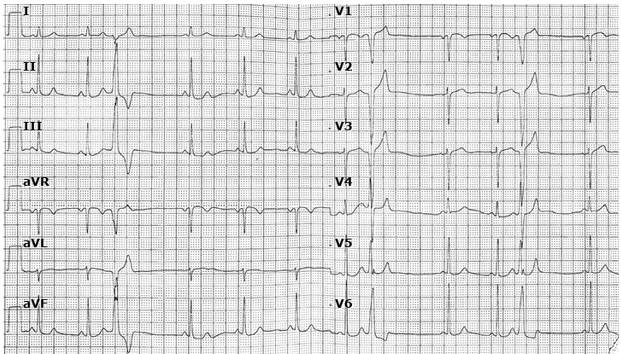

Các phức hợp thất sớm đường ra thất trái

Các phức hợp thất sớm đường ra thất phải

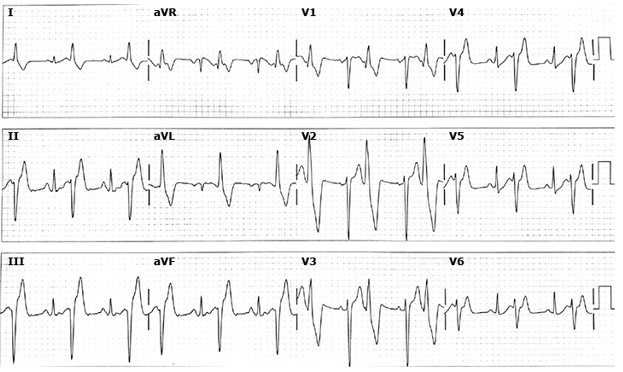

Điện tâm đồ phức bộ thất sớm bó trái

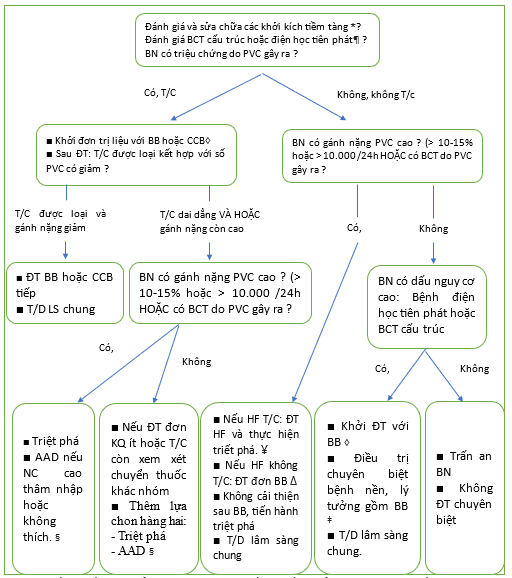

Thuật toán tiếp cận ngoại tâm thu

ACE: chất ức chế men chuyển angiotensin; ARB: thuốc ức chế thụ thể angiotensin; BB: thuốc chẹn beta; CCB: thuốc chẹn kênh canxi; CMP: bệnh cơ tim; HF: suy tim; HTN: tăng huyết áp; PVC: phức hợp/co bóp thất sớm.

* Điều quan trọng là phải đánh giá các tác nhân kích thích PVC tiềm ẩn vì những thay đổi đơn giản trong lối sống có thể tỏ ra hiệu quả (ví dụ, giảm hoặc loại bỏ rượu, cà phê hoặc trà, hoặc kiêng các loại thuốc giải trí/kích thích). Các yếu tố kích thích khác cần được xem xét bao gồm bất thường về điện giải, thiếu oxy, trạng thái cường adrenergic và tăng huyết áp không kiểm soát được.

¶ Việc đánh giá bệnh tim cấu trúc và bệnh điện học nguyên phát thường bao gồm việc xem xét kỹ lưỡng ECG 12 chuyển đạo cũng như siêu âm tim và, trong một số trường hợp được chọn, kiểm tra gắng sức và/hoặc chụp cộng hưởng từ tim.

Δ Nếu đơn trị liệu với BB hoặc CCB dẫn đến sự thay đổi tối thiểu hoặc không có thay đổi về triệu chứng, hãy ngừng thuốc ban đầu và xem xét thử nghiệm đơn trị liệu với thuốc thuộc nhóm khác.

◊ Bệnh nhân mắc bệnh cơ tim có hoặc không có triệu chứng suy tim không nên điều trị bằng CCB. Bệnh nhân có bệnh cơ tim không đáp ứng kịp thời với liệu pháp ức chế beta (tức là giảm gánh nặng PVC và cải thiện phân suất tống máu thất trái) nên được chuyển đi can thiệp điện sinh lý triệt phá qua catheter.

- Đối với những bệnh nhân có các triệu chứng liên quan đến PVC tiếp diễn sau điều trị nội khoa khởi đầu, hoặc đối với những người không dung nạp điều trị nội khoa do tác dụng phụ, người ta đề nghị triệt phá qua catheter, thay vì điều trị bằng thuốc chống loạn nhịp, là phương pháp điều trị tiếp theo. Tuy nhiên, đối với những bệnh nhân không có bệnh tim cấu trúc, triệt phá qua catheter hoặc bắt đầu phương pháp tiếp cận thuốc chống loạn nhịp nhóm IC là lựa chọn tiếp theo hợp lý, mặc dù hiệu quả lâu dài của triệt phá qua ống thông có thể cao hơn.

¥ Tham khảo nội dung khác về HF với phân suất tống máu giảm để biết thêm chi tiết về các liệu pháp điều trị HF tiêu chuẩn.

‡ Ví dụ về bệnh tim tiềm ẩn bao gồm CAD, bệnh cơ tim phì đại, bệnh cơ tim thất phải gây rối loạn nhịp tim, v.v. Tham khảo nội dung khác cụ thể về rối loạn quan tâm để biết thêm chi tiết điều trị.

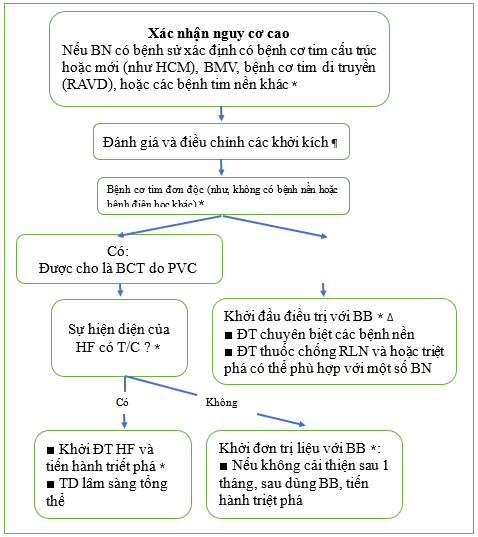

Thuật toán tiếp cận điều trị phức hợp tâm thất sớm ở bệnh nhân có nguy cơ cao

* Tham khảo thêm các nội dung khác.

¶ Các tác nhân giảm nhẹ: giảm hoặc loại bỏ rượu, cà phê hoặc trà; kiêng các thuốc giải trí/kích thích; và điều chỉnh các bất thường điện giải, thiếu oxy, cường adrenergic và tăng huyết áp không kiểm soát được.

Δ Đôi khi, bệnh nhân sẽ muốn dừng thuốc chẹn beta sau khi đã giảm triệu chứng. Trong trường hợp này, người ta có thể thử cai thuốc chẹn beta sau 6 đến 12 tháng điều trị bằng thuốc. Có thể giảm liều dần dần và có thể lặp lại việc ghi Holter 24 giờ theo định kỳ. Tốt nhất nên cho bệnh nhân sử dụng ít nhất một liều thấp thuốc chẹn beta nếu họ sẵn lòng, vì điều này có thể ngăn ngừa tái phát PVC.

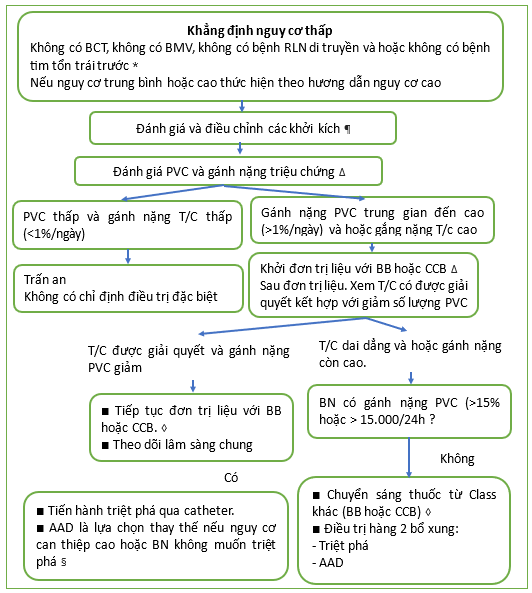

Tiếp cận ngoại tâm thu thất nguy cơ thấp

PVC: phức hợp/co tâm thất sớm; BB: thuốc chặn beta; CCB: thuốc chẹn kênh canxi.

* Ví dụ về các bệnh tim đã có từ trước khác gồm bệnh động mạch vành, bệnh cơ tim phì đại, bệnh cơ tim thất phải gây rối loạn nhịp tim, v.v. Hãy tham khảo nội dung chuyên sâu khác cụ thể để biết thêm thông tin.

¶ Giảm hoặc loại bỏ rượu, cà phê hoặc trà và kiêng các loại thuốc giải trí /kích thích. Điều chỉnh các rối loạn điện giải, tình trạng thiếu oxy, tình trạng tăng adrenergic và tăng huyết áp không kiểm soát được. Tham khảo các nội dung có liên quan để biết thêm chi tiết.

Δ Gánh nặng PVC có thể được đánh giá bằng theo dõi tim 24 giờ. Tham khảo các phần chuyên sau khác để biết thêm thông tin về theo dõi tim, gánh nặng PVC và đánh giá triệu chứng. Trong thực hành ở Việt nam chúng tôi để nghị các đồng nghiệp thay vì theo dõi số thượng ngoại tâm thu trong 1 phút, chúng ta chuyển sang đánh giá số lượng ngoại tâm thu trong 100 chu kỳ phút để đánh giá và theo dõi số lượng có thay đổi trước, và sau mỗi đợt trị liệu bằng các thuốc chẹn beta, chẹn kênh can xin hoặc các thuốc chống loạn nhịp khác.

◊ Ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng và gánh nặng thấp hơn hoặc không có sau khi điều trị bằng BB hoặc CCB và muốn dừng hoặc giảm liều thuốc, việc thử cai thuốc và/hoặc dừng thuốc có thể được thực hiện sau 6-12 tháng. Tham khảo nội dung các phần khác trong bài để biết thêm chi tiết.

- Tham khảo nội dung khác để biết thêm chi tiết

Các thuốc được sử dụng điều trị ngoại tâm thu

| Thuốc | Liều khởi | Liều max | Các xem xét khác |

| Beta blockers | |||

| Metoprolol IR | 25 mg hai lần ngày | 400 mg mỗi ngày được chia 2 hoặc 3 liều) (liều cao hơn 100 mg 2 lần ngày hiếm khi sử dụng) | Thường được sử dụng |

| Metoprolol succinate ER | 50 mg một lần ngày | 400 mg mỗi ngày (liều cao hơn 200mg một lần ngày hiếm khi được sử dụng) | Có thể được sử dụng ở bệnh nhân HFrEF với liều khởi đầu thấp hơn từ 12,5 đến 25 mg mỗi ngày một lần |

| Carvedilol IR | 3.125 mg 2 lần ngày | 25 mg 2 lần ngày | Thường được sử dụng; có thể được sử dụng ở bệnh nhân HFrEF |

| Bisoprolol | 2.5 mg lần ngày | 10 mg mỗi lần ngày | |

| Nebivolol | 5 mg lần ngày | 40 mg once daily | Liều thấp hơn từ 1,25 đến 10 mg được sử dụng ở bệnh nhân suy tim |

| Atenolol | 25 mg một lần ngày | 200 mg mỗi ngày (liều cao hơn 100mg mỗi ngày hiếm khi được sử dụng) | Tránh ở các bệnh nhân HF |

| Nadolol | 40 mg mỗi ngày | 120 mg hàng ngày | Tránh dùng ở bệnh nhân suy tim; liệu pháp lựa chọn đầu tiên trong một số bệnh lý kênh |

| Betaxolol | 5 mg mỗi ngày | 20 mg mỗi ngày | Tránh ở các bệnh nhân HF |

| Propranolol IR | 10 mg 2 hoặc 3 lần ngày | 80 mg mỗi ngày 2 lần hàng ngày | Tránh dùng ở bệnh nhân suy tim; liệu pháp lựa chọn đầu tiên trong một số bệnh kênh và cường giáp |

| Propranolol LA | 80 mg lần ngày | 160 mg lần ngày | Tránh dùng ở bệnh nhân suy tim; liệu pháp lựa chọn đầu tiên trong một số bệnh kênh và cường giáp |

| Blocker kênh canxi* | |||

| Diltiazem (12 -h) | 60 mg 2 lần ngày | 180 mg 2 lần ngày | |

| Diltiazem ER (24-h) | 120 mg lần ngày | 360 mg lần ngày | |

| Verapamil IR | 40 or 80 mg 3 lần ngày | 120 mg 3 lần ngày | |

| Verapamil ER | 120 hoặc 180 mg một lần ngày | 360 mg một lần ngày hoặc 180 mg 2 lần ngày | |

Liều lượng tối đa ban đầu và thông thường để giảm gánh nặng PVC. Liều ban đầu có thể được điều chỉnh (ví dụ, cách nhau hai tuần) khi cần thiết để giảm các triệu chứng tương ứng với việc giảm PVC.

IR: tiết ngay lập tức; ER: tiết mở rộng; LA: tiết lâu dài; HFrEF: suy tim với phân suất tống máu giảm; PVC: phức hợp tâm thất sớm.

* Ở những bệnh nhân không giảm phân suất tống máu thất trái hoặc bệnh tim cấu trúc, có thể thay thế thuốc chẹn kênh canxi không dihydropyridine nếu thuốc chẹn beta không được dung nạp hoặc không thành công trong việc giảm triệu chứng. Bệnh nhân có bệnh cơ tim, có hoặc không có triệu chứng suy tim, không nên điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn kênh canxi.

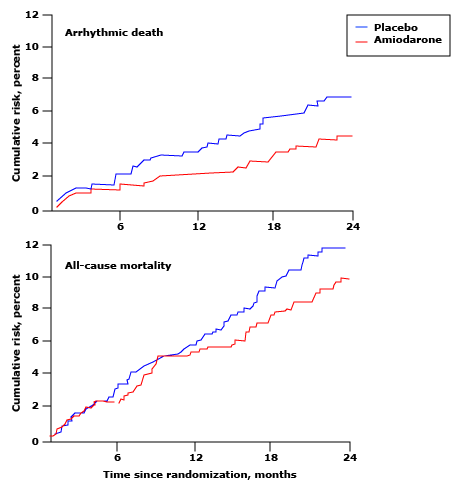

Hiệu quả amiodarone trong nghiên cứu CAMIAT

Hiệu quả của amiodarone so với giả dược ở 1202 bệnh nhân sau nhồi máu cơ tim có ngoại vị tâm thất trong thử nghiệm CAMIAT. Bằng mục đích phân tích điều trị, amiodarone đã làm giảm đáng kể tỷ lệ tử vong do rối loạn nhịp tim (biểu đồ trên cùng, p = 0,016) nhưng không thay đổi về tỷ lệ tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân (biểu đồ dưới cùng).

Bảng tóm tắt phân loại thuốc chống loạn nhịp của Vaughan Williams được sửa đổi năm 2018

| Class 0 (HCN channel blockers) |

| Ivabradine |

| Class I (Blocker kênh Na+ cổng điện thế) |

| Class Ia (phân ly trung gian): |

| ♦ Quinidine, ajmaline, disopyramide, procainamide |

| Class Ib (phân ly nhanh): |

| ♦ Lidocaine, mexilitine |

| Class Ic (phân ly chậm): |

| ♦ Propafenone, flecainide |

| Class Id (dòng muộn): |

| ♦ Ranolazine |

| Class II (chất ức chế và kích hoạt tự động) |

| Class IIa (beta blockers): |

| ♦ Không chọn lọc: carvedilol, propranolol, nadolol |

| ♦ Chọn lọc: atenolol, bisoprolol, betaxolol, celiprolol, esmolol, metoprolol |

| Class IIb (chất chủ vận beta không chọn lọc): |

| ♦ Isoproterenol |

| Class IIc (chất ức chế thụ thể muscarinic M2): |

| ♦ Atropine, anisodamine, hyoscine, scopolamine |

| Class IId (chất kích hoạt thụ thể muscarinic M2): |

| ♦ Carbachol, pilocarpine, methacholine, digoxin |

| Class IIe (chất kích hoạt thụ thể adenosine A1): |

| ♦ Adenosine |

| Class III (chẹn và mở kênh K+) |

| Class IIIa (blocker kênh K+ phụ thuốc điện thế): |

| ♦ Ambasilide, amiodarone, dronedarone, dofetilide, ibutilide, sotalol, vernakalant |

| Class IIIb (mỏ kênh K+ phụ thuộc chuyển hoá): |

| ♦ Nicorandil, pinacidil |

| Class IV (điều biến xử lý Ca++) |

| Class IVa (blocker Ca ++ bề mặt màng tế bào): |

| ♦ Bepridil, diltiazem, verapamil |

| Class IVb (blocker kệnh Ca++ nội bào): |

| ♦ Flecainide, propafenone |

| Class V (blocker kênh nhạy cảm cơ học): |

| Không có thuốc được phê duyệt |

| Class VI (blocker kênh nối khoảng cách) |

| Không có thuốc được phê duyệt |

| Class VII (Điều biến hướng đích) (upstream target modulators) |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers |

| Omega-3 fatty acids |

| Statins |

HCN: hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated: nucleotide vòng được kích hoạt siêu phân cực; Na: natri; K: kali; Ca: can xi.

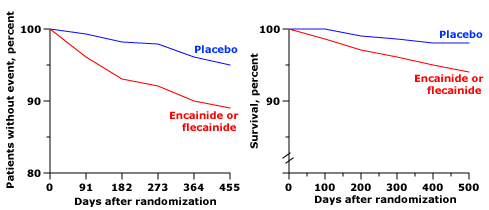

Encainide và flecainide làm tăng tử suất tim mạch

Kết quả thử nghiệm ức chế rối loạn nhịp tim (Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial: CAST) ở bệnh nhân có nhịp thất sớm sau nhồi máu cơ tim. Khi so sánh với những bệnh nhân dùng giả dược, bệnh nhân dùng encainide hoặc flecainide có tỷ lệ tránh được biến cố tim mạch (tử vong hoặc ngừng tim được hồi sức) thấp hơn đáng kể (hình bên trái, p = 0,001) và tỷ lệ sống sót tổng thể thấp hơn (hình bên phải, p = 0,0006) ). Nguyên nhân tử vong là do rối loạn nhịp tim hoặc ngừng tim.

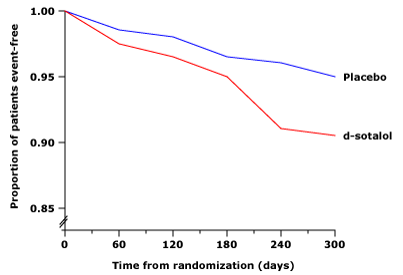

Sống sót bị giảm với sotalol trong nghiên cứu SWORD

Kết quả từ thử nghiệm SWORD (Survival With Oral d-Sotalol: SWORD). Việc sử dụng d-sotalol cho bệnh nhân có phân suất tống máu ≤ 40% sau nhồi máu cơ tim (MI) gần đây hoặc sau suy tim có triệu chứng với nhồi máu cơ tim lâu hơn (>42 ngày) có liên quan đến tăng tỷ lệ tử vong so với giả dược (5 so với 3,1%). ). Số lượng tử vong tăng hơn được cho là chủ yếu là do rối loạn nhịp tim.

Kết luận:

Trước khi quyết định điều trị ngoại tâm thu thất, chúng ta thường phải trả lời các câu hỏi sau:

- PVC có phải do các yếu tố có thể đảo ngược được hay không ?

- PVC có phải là loại nguy hiểm hay không ?

- PVC có gắn liền với bệnh tim cấu trúc không ?

- PVC cơ năng hay thực thể (có liên quan đến gắng sức hay không) ?

- PVC có gây ra triệu chứng không ? Và gánh nặng của nó là cao hay thấp ?

Tài liệu tham khảo

- Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2793.

- Lip GY, Heinzel FR, Gaita F, et al. European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Failure Association joint consensus document on arrhythmias in heart failure, endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2016; 18:12.

- Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Executive summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15:e190.

- Dukes JW, Dewland TA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Ventricular Ectopy as a Predictor of Heart Failure and Death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66:101.

- Ip JE, Lerman BB. Idiopathic malignant premature ventricular contractions. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2018; 28:295.

- Dabbagh GS, Bogun F. Predictors and Therapy of Cardiomyopathy Caused by Frequent Ventricular Ectopy. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017; 19:80.

- Supple GE. Editorial commentary: Malignant PVCs: Revising the ‘idiopathic’ label. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2018; 28:303.

- Carballeira Pol L, Deyell MW, Frankel DS, et al. Ventricular premature depolarization QRS duration as a new marker of risk for the development of ventricular premature depolarization-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2014; 11:299.

- Park KM, Im SI, Lee SH, et al. Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Outpatients with Frequent Ventricular Premature Complexes. Tex Heart Inst J 2022; 49.

- Yokokawa M, Kim HM, Good E, et al. Impact of QRS duration of frequent premature ventricular complexes on the development of cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9:1460.

- Yamada T. Twelve-lead electrocardiographic localization of idiopathic premature ventricular contraction origins. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019; 30:2603.

- Park KM, Kim YH, Marchlinski FE. Using the surface electrocardiogram to localize the origin of idiopathic ventricular tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2012; 35:1516.

- Olgun H, Yokokawa M, Baman T, et al. The role of interpolation in PVC-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2011; 8:1046.

- Viskin S, Lesh MD, Eldar M, et al. Mode of onset of malignant ventricular arrhythmias in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1997; 8:1115.

- Leenhardt A, Glaser E, Burguera M, et al. Short-coupled variant of torsade de pointes. A new electrocardiographic entity in the spectrum of idiopathic ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation 1994; 89:206.

- Sadek MM, Benhayon D, Sureddi R, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the moderator band: Electrocardiographic characteristics and treatment by catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm 2015; 12:67.

- Lin CY, Chang SL, Lin YJ, et al. Long-term outcome of multiform premature ventricular complexes in structurally normal heart. Int J Cardiol 2015; 180:80.

- Bradfield JS, Homsi M, Shivkumar K, Miller JM. Coupling interval variability differentiates ventricular ectopic complexes arising in the aortic sinus of valsalva and great cardiac vein from other sources: mechanistic and arrhythmic risk implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2151.

- Limpitikul WB, Dewland TA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Premature ventricular complexes and development of heart failure in a community-based population. Heart 2022; 108:105.

- Shimizu W. Arrhythmias originating from the right ventricular outflow tract: how to distinguish “malignant” from “benign”? Heart Rhythm 2009; 6:1507.

- Noda T, Shimizu W, Taguchi A, et al. Malignant entity of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia initiated by premature extrasystoles originating from the right ventricular outflow tract. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:1288.

- Abdalla IS, Prineas RJ, Neaton JD, et al. Relation between ventricular premature complexes and sudden cardiac death in apparently healthy men. Am J Cardiol 1987; 60:1036.

- Sajadieh A, Nielsen OW, Rasmussen V, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias and risk of death and acute myocardial infarction in apparently healthy subjects of age >or=55 years. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:1351.

- Bikkina M, Larson MG, Levy D. Prognostic implications of asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmias: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117:990.

- Gopinathannair R, Etheridge SP, Marchlinski FE, et al. Arrhythmia-Induced Cardiomyopathies: Mechanisms, Recognition, and Management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66:1714.

- Lee AK, Deyell MW. Premature ventricular contraction-induced cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol 2016; 31:1.

- Latchamsetty R, Yokokawa M, Morady F, et al. Multicenter Outcomes for Catheter Ablation of Idiopathic Premature Ventricular Complexes. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2015; 1:116.

- Giles K, Green MS. Workup and management of patients with frequent premature ventricular contractions. Can J Cardiol 2013; 29:1512.

- Manolis AA, Manolis TA, Apostolopoulos EJ, et al. The role of the autonomic nervous system in cardiac arrhythmias: The neuro-cardiac axis, more foe than friend? Trends Cardiovasc Med 2021; 31:290.

- Yokokawa M, Siontis KC, Kim HM, et al. Value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and programmed ventricular stimulation in patients with frequent premature ventricular complexes undergoing radiofrequency ablation. Heart Rhythm 2017; 14:1695.

- Yamada T. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias: Relevance to the anatomy, diagnosis and treatment. J Cardiol 2016; 68:463.

- Oebel S, Dinov B, Arya A, et al. ECG morphology of premature ventricular contractions predicts the presence of myocardial fibrotic substrate on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients undergoing ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2017; 28:1316.

- Brunetti G, Cipriani A, Perazzolo Marra M, et al. Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Evaluation of Athletes with Premature Ventricular Beats. J Clin Med 2022; 11.

- Muser D, Santangeli P, Castro SA, et al. Risk Stratification of Patients With Apparently Idiopathic Premature Ventricular Contractions: A Multicenter International CMR Registry. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2020; 6:722.

- Hosseini F, Thibert MJ, Gulsin GS, et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in the Evaluation of Patients With Frequent Premature Ventricular Complexes. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2022; 8:1122.

- Pellegrino PL, Casavecchia G, Gravina M, et al. Concealed structural heart disease discovered at cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with ventricular extrasystoles from ventricular outflow tract and apparently normal hearts. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2021; 61:45.

- Lip GYH, Coca A, Kahan T, et al. Hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias: a consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and ESC Council on Hypertension, endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulación Cardíaca y Electrofisiología (SOLEACE). Europace 2017; 19:891.

- Muser D, Tritto M, Mariani MV, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Premature Ventricular Contractions: A Stepwise Approach Based on the Site of Origin. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021; 11.

- Ghannam M, Siontis KC, Kim MH, et al. Risk stratification in patients with frequent premature ventricular complexes in the absence of known heart disease. Heart Rhythm 2020; 17:423.

- Tang JKK, Andrade JG, Hawkins NM, et al. Effectiveness of medical therapy for treatment of idiopathic frequent premature ventricular complexes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2021; 32:2246.

- Zhong L, Lee YH, Huang XM, et al. Relative efficacy of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs in treating premature ventricular contractions: a single-center retrospective study. Heart Rhythm 2014; 11:187.

- Chandraratna PA. Comparison of acebutolol with propranolol, quinidine, and placebo: results of three multicenter arrhythmia trials. Am Heart J 1985; 109:1198.

- Hasdemir C, Ulucan C, Yavuzgil O, et al. Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy in patients with idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias: the incidence, clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics, and the predictors. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2011; 22:663.

- Baman TS, Lange DC, Ilg KJ, et al. Relationship between burden of premature ventricular complexes and left ventricular function. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7:865.

- Takemoto M, Yoshimura H, Ohba Y, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of premature ventricular complexes from right ventricular outflow tract improves left ventricular dilation and clinical status in patients without structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:1259.

- Wijnmaalen AP, Delgado V, Schalij MJ, et al. Beneficial effects of catheter ablation on left ventricular and right ventricular function in patients with frequent premature ventricular contractions and preserved ejection fraction. Heart 2010; 96:1275.

- Yarlagadda RK, Iwai S, Stein KM, et al. Reversal of cardiomyopathy in patients with repetitive monomorphic ventricular ectopy originating from the right ventricular outflow tract. Circulation 2005; 112:1092.

- Yokokawa M, Good E, Crawford T, et al. Recovery from left ventricular dysfunction after ablation of frequent premature ventricular complexes. Heart Rhythm 2013; 10:172.

- Marcus GM. Evaluation and Management of Premature Ventricular Complexes. Circulation 2020; 141:1404.

- Lamba J, Redfearn DP, Michael KA, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation for the treatment of idiopathic premature ventricular contractions originating from the right ventricular outflow tract: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014; 37:73.

- Deyell MW, Park KM, Han Y, et al. Predictors of recovery of left ventricular dysfunction after ablation of frequent ventricular premature depolarizations. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9:1465.

- Im SI, Voskoboinik A, Lee A, et al. Predictors of long-term success after catheter ablation of premature ventricular complexes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2021; 32:2254.

- Oomen AWGJ, Dekker LRC, Meijer A. Catheter ablation of symptomatic idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias : A five-year single-centre experience. Neth Heart J 2018; 26:210.

- Wang JS, Shen YG, Yin RP, et al. The safety of catheter ablation for premature ventricular contractions in patients without structural heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2018; 18:177.

- Cojocaru C, Penela D, Berruezo A, Vatasescu R. Mechanisms, time course and predictability of premature ventricular contractions cardiomyopathy-an update on its development and resolution. Heart Fail Rev 2022; 27:1639.

- Penela D, Jáuregui B, Fernández-Armenta J, et al. Influence of baseline QRS on the left ventricular ejection fraction recovery after frequent premature ventricular complex ablation. Europace 2020; 22:274.

- Cairns JA, Connolly SJ, Roberts R, Gent M. Randomised trial of outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with frequent or repetitive ventricular premature depolarisations: CAMIAT. Canadian Amiodarone Myocardial Infarction Arrhythmia Trial Investigators. Lancet 1997; 349:675.

- Julian DG, Camm AJ, Frangin G, et al. Randomised trial of effect of amiodarone on mortality in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction after recent myocardial infarction: EMIAT. European Myocardial Infarct Amiodarone Trial Investigators. Lancet 1997; 349:667.

- Singh SN, Fletcher RD, Fisher SG, et al. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:77.

- Murray GL. Ranolazine is an Effective and Safe Treatment of Adults with Symptomatic Premature Ventricular Contractions due to Triggered Ectopy. Int J Angiol 2016; 25:247.

- Yeung E, Krantz MJ, Schuller JL, et al. Ranolazine for the suppression of ventricular arrhythmia: a case series. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2014; 19:345.

- Nanda S, Levin V, Martinez MW, Freudenberger R. Ranolazine–treatment of ventricular tachycardia and symptomatic ventricular premature beats in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2010; 33:e119.

- Murdock DK, Kaliebe JW. Suppression of frequent ventricular ectopy in a patient with hypertrophic heart disease with ranolazine: a case report. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2011; 11:84.

- Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Hod H, et al. Effect of ranolazine, an antianginal agent with novel electrophysiological properties, on the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from the Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36) randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2007; 116:1647.

- Polytarchou K, Manolis AS. Ranolazine and its Antiarrhythmic Actions. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem 2015; 13:31.

- Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:781.

- Waldo AL, Camm AJ, deRuyter H, et al. Effect of d-sotalol on mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after recent and remote myocardial infarction. The SWORD Investigators. Survival With Oral d-Sotalol. Lancet 1996; 348:7.

- Hyman MC, Mustin D, Supple G, et al. Class IC antiarrhythmic drugs for suspected premature ventricular contraction-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15:159.

- Penela D, Acosta J, Aguinaga L, et al. Ablation of frequent PVC in patients meeting criteria for primary prevention ICD implant: Safety of withholding the implant. Heart Rhythm 2015; 12:2434.

- Podrid PJ, Fogel RI, Fuchs TT. Ventricular arrhythmia in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1992; 69:82G.

- Chadda K, Goldstein S, Byington R, Curb JD. Effect of propranolol after acute myocardial infarction in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 1986; 73:503.

- Lichstein E, Morganroth J, Harrist R, Hubble E. Effect of propranolol on ventricular arrhythmia. The beta-blocker heart attack trial experience. Circulation 1983; 67:I5.

- Manolis AS. The clinical challenge of preventing sudden cardiac death immediately after acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2014; 12:1427.

- Hayes DL, Boehmer JP, Day JD, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy and the relationship of percent biventricular pacing to symptoms and survival. Heart Rhythm 2011; 8:1469.

- Lakkireddy D, Di Biase L, Ryschon K, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of premature ventricular ectopy improves the efficacy of cardiac resynchronization therapy in nonresponders. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:1531.

- Yokokawa M, Kim HM, Good E, et al. Relation of symptoms and symptom duration to premature ventricular complex-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9:92.

- Lee AKY, Andrade J, Hawkins NM, et al. Outcomes of untreated frequent premature ventricular complexes with normal left ventricular function. Heart 2019; 105:1408.

- Latchamsetty R, Bogun F. Premature Ventricular Complex-Induced Cardiomyopathy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019; 5:537.

- Podrid PJ, Lampert S, Graboys TB, et al. Aggravation of arrhythmia by antiarrhythmic drugs–incidence and predictors. Am J Cardiol 1987; 59:38E.

- Madias C, Estes NAM 3rd. Class IC antiarrhythmic agents in structural heart disease: Is nothing CAST in stone? Heart Rhythm 2018; 15:164.

- Lee V, Hemingway H, Harb R, et al. The prognostic significance of premature ventricular complexes in adults without clinically apparent heart disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Heart 2012; 98:1290.

- Lin CY, Chang SL, Lin YJ, et al. An observational study on the effect of premature ventricular complex burden on long-term outcome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96:e5476.

- Agarwal SK, Heiss G, Rautaharju PM, et al. Premature ventricular complexes and the risk of incident stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) Study. Stroke 2010; 41:588.

- Agarwal SK, Chao J, Peace F, et al. Premature ventricular complexes on screening electrocardiogram and risk of ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015; 46:1365.

- Boas R, Thune JJ, Pehrson S, et al. Prevalence and prognostic association of ventricular arrhythmia in non-ischaemic heart failure patients: results from the DANISH trial. Europace 2021; 23:587.

- Ruwald AC, Aktas MK, Ruwald MH, et al. Postimplantation ventricular ectopic burden and clinical outcomes in cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator patients: a MADIT-CRT substudy. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2018; 23:e12491.

- Bhonsale A, James CA, Tichnell C, et al. Incidence and predictors of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy undergoing implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation for primary prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:1485.

- Manolis TA, Manolis AA, Apostolopoulos EJ, et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in pregnant women: need for mother and offspring protection. Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36:1225.

- Cox JL, Gardner MJ. Treatment of cardiac arrhythmias during pregnancy. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1993; 36:137.

- Newcombe PF, Renton KW, Rautaharju PM, et al. High-dose caffeine and cardiac rate and rhythm in normal subjects. Chest 1988; 94:90.

- Myers MG. Caffeine and cardiac arrhythmias. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:147.

- Newby DE, Neilson JM, Jarvie DR, Boon NA. Caffeine restriction has no role in the management of patients with symptomatic idiopathic ventricular premature beats. Heart 1996; 76:355.

- Tong C, Kiess M, Deyell MW, et al. Impact of frequent premature ventricular contractions on pregnancy outcomes. Heart 2018; 104:1370.