Trưởng ban: PGS.TS PHẠM NGUYỄN VINH

Đồng trưởng ban: TS.BS NGUYỄN THỊ THU HOÀI

(…)

6.3 Điều trị bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ

Rung nhĩ thường xảy ra ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ, làm giảm cung lượng tim, giảm chất lượng cuộc sống và làm tăng nguy cơ đột quỵ. Điều trị bao gồm phòng ngừa thuyên tắc do huyết khối và kiểm soát triệu chứng. Điểm số nguy cơ đột quỵ truyền thống được sử dụng trong dân số chung không dự báo nguy cơ đột quỵ ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ. Rung nhĩ được phát hiện qua những dụng cụ đặt trong tim hoặc theo dõi bằng màn hình ở những bệnh nhân không triệu chứng cũng làm gia tăng khả năng đột quỵ. Vì vậy, kháng đông cần được cân nhắc ở những bệnh nhân này. Kháng vitamin K và thuốc kháng đông uống tác dụng trực tiếp (DOAC) đều có hiệu quả phòng ngừa đột quỵ ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ. Trong trường hợp cần kiểm soát nhịp, một số thuốc chống loạn nhịp cho thấy có hiệu quả và an toàn; việc chọn lựa thuốc nên được cá nhân hóa. Một số biện pháp can thiệp như triệt đốt qua đường ống thông, giảm dầy tiểu nhĩ trái, phẫu thuật Maze được sử dụng. Cắt đốt qua ống thông ít hiệu quả hơn trong dân số chung và có thể cần lặp lại nhiều lần và cần phối hợp với thuốc chống loạn nhịp. Giảm dầy tiểu nhĩ trái là một chọn lựa điều trị nhịp ở bệnh nhân phẫu thuật cắt vách. Phẫu thuật Maze ít khi được thực hiện đơn độc. Các loạn nhịp trên thất khác và cuồng nhĩ xảy ra không nhiều hơn và điều trị thường tương tự như người không mắc BCTPĐ.

Nguy cơ thuyên tắc hệ thống được ghi nhận trong một phân tích tổng hợp với 7381 bệnh nhân rung nhĩ là 27,09%(175). Trong phân tích tổng hợp (meta-analysis) được đề cập, 25,7% bệnh nhân đột quỵ có chỉ số CHA2DS2-VASC bằng 0; từ đó gợi ý nguy cơ đột quỵ độc lập với chỉ số này ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ. Warfarin có khả năng làm giảm nguy cơ đột quỵ ở người BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ, đặc biệt với INR 2 – 3. Trong những năm gần đây, nhiều nghiên cứu đã chứng minh hiệu quả không thua kém của DOAC so với warfarin bên cạnh nhiều lợi ích cộng thêm của DOAC như sự thuận tiện khi dùng thuốc, kết cục lâu dài(176–178). Khuyến cáo dùng kháng đông ở bệnh nhân cuồng nhĩ tương tự như ở bệnh nhân rung nhĩ(179).

Tương tự như ở người không mắc BCTPĐ, rung nhĩ dưới lâm sàng ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ không triệu chứng có thể được phát hiện qua dụng cụ gắn ở tim và tỷ lệ này được báo cáo là 53% sau thời gian theo dõi 595 ngày(180). Ở người không mắc BCTPĐ, rung nhĩ dưới lâm sàng làm gia tăng nguy cơ thuyên tắc do huyết khối, nhưng thấp hơn so với rung nhĩ lâm sàng(181). Ngưỡng thời gian rung nhĩ để bắt đầu kháng đông trong rung nhĩ dưới lâm sàng thay đổi đáng kể giữa các nghiên cứu. Tuy nhiên, nhiều dữ liệu cho thấy cơn rung nhĩ càng kéo dài, hoặc kết hợp các yếu tố nguy cơ khác (tuổi cao, tiền căn thuyên tắc, phân độ NYHA, đường kính nhĩ trái, bệnh lý mạch máu, bề dầy thành thất trái tối đa) thì nguy cơ càng cao. Dữ liệu từ nghiên cứu ASSERT (Atrial Fibrillation Reduction Atrial Pacing Trial) cho thấy cơn rung nhĩ kéo dài trên 24 giờ làm tăng nguy cơ. Trong khi đó, những cơn rung nhĩ rất ngắn kéo dài một vài giây không làm tăng nguy cơ.

Vì khả năng dung nạp rung nhĩ kém nên chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp được ưa chuộng ở người BCTPĐ (182). Thuốc được dùng để chuyển nhịp bao gồm amiodarone, disopyramide được cho thấy an toàn và hiệu quả. Thuốc chống loạn nhịp khuyến cáo loại 1c được dùng an toàn nhất khi bệnh nhân được đặt ICD(182). Thuốc khuyến cáo loại 3 cũng có thể được chỉ định. Sotalol an toàn và thường được dùng cho trẻ em cả đường uống và đường tĩnh mạch(183).

Ở những bệnh nhân được áp dụng chiến lược kiểm soát tần số, thuốc ức chế kênh calci non-dihydropyridine, chẹn beta hoặc kết hợp cả hai được ưa dùng. Digoxin có thể được chỉ định khi ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ không tắc nghẽn. Ở những bệnh nhân tụt huyết áp, khó thở khi nghỉ và chênh áp qua đường ra thất trái lúc nghỉ rất cao (trên 100 mmHg), verapamil nên tránh dùng. Đốt nút nhĩ thất cùng với đặt máy tạo nhịp, có thể là chọn lựa sau cùng ở những trường hợp không đáp ứng với điều trị bằng thuốc.

Cắt đốt qua ống thông là thủ thuật an toàn và đóng vai trò quan trọng trong điều trị rung nhĩ. Kết quả từ các nghiên cứu cho thấy, tỷ lệ tái phát cao gấp hai lần, tần suất lặp lại của thủ thuật và sử dụng đồng thời thuốc chống loạn nhịp cao hơn ở người BCTPĐ so với người không mắc BCTPĐ(184). Sự khác biệt này là do tái cấu trúc nhĩ với các yếu tố góp phần bao gồm nghẽn đường ra thất trái, suy chức năng tâm trương, hở van hai lá và các yếu tố khác.

Cắt rung nhĩ bằng phẫu thuật là phương pháp kiểm soát nhịp có tiềm năng, đặc biệt là khi bệnh nhân có phẫu thuật tim hở nhằm mục đích cắt vách. Giảm nghẽn đường ra thất trái cùng với giảm mức độ hở van hai lá có thể hạn chế hoặc thậm chí đảo ngược tái cấu trúc nhĩ trái(185). Trong một nghiên cứu gần đây, báo cáo loạt ca lớn nhất về điều trị rung nhĩ bằng phẫu thuật cho thấy 44% số bệnh nhân (n = 49) không tái phát rung nhĩ ở thời điểm một năm và 79% số bệnh nhân (n = 72) được áp dụng phẫu thuật Maze (p dưới 0,001)(182).

| Loại | MCC | Khuyến cáo về điều trị rung nhĩ |

| 1 | B | 1. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ lâm sàng, kháng đông được khuyên dùng với thuốc kháng đông uống tác dụng trực tiếp (DOAC) là chọn lựa hàng đầu và kháng vitamin K là chọn lựa hàng thứ hai, không phụ thuộc vào điểm CHA2DS2-VASC(176,186–189). |

| 1 | C | 2. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ dưới lâm sàng được phát hiện qua dụng cụ đặt trong hoặc ngoài tim hoặc trên màn hình với cơn kéo dài trên 24 giờ, thuốc kháng đông uống tác dụng trực tiếp (DOAC) là chọn lựa hàng đầu và kháng vitamin K là chọn lựa hàng thứ hai, không phụ thuộc vào điểm CHA2DS2-VASC (190,191). |

| 1 | C | 3. Bệnh nhân rung nhĩ cần kiểm soát tần số, chẹn beta hoặc verapamil, hoặc diltiazem được khuyên dùng với việc chọn lựa thuốc tùy vào sự ưa thích của bệnh nhân và bệnh đồng mắc(182,183). |

| 2a | B | 4. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ dưới lâm sàng, được phát hiện qua dụng cụ đặt trong hoặc ngoài tim hoặc trên màn hình với cơn kéo dài trên 5 phút nhưng dưới 24 giờ, thuốc kháng đông uống tác dụng trực tiếp (DOAC) là chọn lựa hàng đầu và kháng vitamin K là chọn lựa hàng thứ hai có thể có lợi, cần tính đến các thời gian của các các cơn rung nhĩ, tổng gánh nặng rung nhĩ, các yếu tố nguy cơ tiềm ẩn và nguy cơ xuất huyết (190,191). |

| 2a | B | 5. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ và dung nạp kém rung nhĩ, chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp với chuyển nhịp hoặc thuốc chống loạn nhịp có thể có lợi với sự lựa chọn thuốc tùy thuộc vào độ nặng của triệu chứng rung nhĩ, sự ưa thích của bệnh nhân và bệnh đồng mắc(183,184). |

| 2a | B | 6. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ và rung nhĩ có triệu chứng, trong chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp, cắt đốt bằng ống thông rung nhĩ có thể có hiệu quả khi thuốc không hiệu quả, chống chỉ định, hoặc không có sự ưa thích của bệnh nhân(192,193). |

| 2a | B | 7. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rung nhĩ cần phẫu thuật cắt vách, cắt rung nhĩ bằng phẫu thuật đồng thời với phẫu thuật tim khác có thể có lợi cho kiểm soát nhịp(182,185,194). |

Bảng 5. Lựa chọn thuốc chống loạn nhịp trên bệnh nhân BCTPĐ và rung nhĩ

| Thuốc chống loạn nhịp | Hiệu quả trên rung nhĩ | Tác dụng phụ | Độc tính | Sử dụng trên BCTPĐ |

| Disopyramide | Ít hiệu quả | Tác dụng cholinergic Suy tim |

Kéo dài QTc | Lúc khởi đầu rung nhĩ |

| Flecainide và propafenone | ? | Tăng loạn nhịp | Không sử dụng khi chưa đặt ICD | |

| Sotalol | Ít hiệu quả | Mệt

Tim chậm |

Kéo dài QTc

Kéo dài QTc Tăng loạn nhịp |

Có thể sử dụng |

| Dofetilide | Ít hiệu quả | Nhức đầu | Tăng loạn nhịp | Có thể sử dụng |

| Dronedarone | Thấp | Suy tim | Kéo dài QTc | ? |

| Amiodarone | Có hiệu quả trung bình | Tim chậm | Gan, phổi, tuyến giáp, da, thần kinh | Có thể sử dụng |

6.4 Điều trị bệnh nhân BCTPĐ và rối loạn nhịp thất

| Loại | MCC | Khuyến cáo điều trị bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rối loạn nhịp thất |

| 1 | B | 1. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có nhịp nhanh thất đe dọa mạng sống, dung nạp kém, tái phát, không đáp ứng với thuốc chống loạn nhịp tối đa và cắt đốt, ghép tim được chỉ định phù hợp theo tiêu chí hiện tại(195,196). |

| 1 | Amiodarone, B | 2. Ở người lớn BCTPĐ với nhịp nhanh thất có triệu chứng hoặc ICD sốc nhiều lần dù đã dùng thuốc chẹn beta, thuốc chống loạn nhịp trong danh sách được khuyên dùng, với sự lựa chọn thuốc dựa vào tuổi, bệnh đồng mắc, độ nặng của bệnh, sự ưa thích của bệnh nhân và sự cân bằng hiệu quả và an toàn(197–200). |

| Dofetilide, C | ||

| Mexilletine, C | ||

| Sotalol, C | ||

| 1 | C | 3. Ở trẻ em BCTPĐ có nhịp nhanh thất tái phát dù đã dùng thuốc chẹn beta, thuốc chống loạn nhịp [amiodarone (197,198) mexiletine(200), sotalol (197–200)] được khuyên dùng, với sự lựa chọn thuốc dựa vào tuổi, bệnh đồng mắc, độ nặng của bệnh, sự ưa thích của bệnh nhân và sự cân bằng hiệu quả và an toàn |

| 1 | C | 4. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ mang ICD có khả năng tạo nhịp, tạo nhịp nhanh theo chương trình được khuyên dùng để tối thiểu nguy cơ sốc(201,202). |

| 2a | C | 5. Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ với nhịp nhanh thất đơn dạng kéo dài có triệu chứng tái phát hoặc ICD sốc nhiều lần dù đã thiết lập chương trình dụng cụ tối ưu và thuốc chống loạn nhịp không hiệu quả hoặc không dung nạp hoặc không được ưa thích, triệt đốt qua đường ống thông được khuyên dùng để tối thiểu nguy cơ sốc điện(203–205). |

Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ đã được đặt ICD, việc phòng ngừa nhịp nhanh thất tái phát là mục tiêu quan trọng vì những cù sốc của ICD làm giảm chất lượng cuộc sống và đưa đến kết cục xấu(206). Có ít dữ liệu liên quan đến điều trị rối loạn nhịp thất ở người BCTPĐ. Sự lựa chọn thuốc nên được cá thể hóa. Tuy nhiên, amiodarone ưu thế hơn cả dù có nhiều tác dụng phụ và không cải thiện tỷ lệ sống còn. ICD lập trình nhịp nhanh có thể tối thiểu hóa nguy cơ sốc vì nhịp nhanh thất đơn dạng và cuồng thất thường xảy ra. Trong trường hợp không đáp ứng với thuốc điều trị rối loạn nhịp và đã tối ưu chương trình ICD, triệt đốt qua đường ống thông là một giải pháp.

Ghép tim nên tuân theo các khuyến cáo hiện tại(207). Ghép tim trong BCTPĐ không đợi đến khi phân suất tống máu giảm vì bệnh nhân có phân suất tống máu bảo tồn cũng có thể phát triển suy tim tiến triển hoặc rối loạn nhịp khó chữa(195,196).

Phần lớn bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có nhịp nhanh thất thường được chỉ định thuốc chẹn beta như là chọn lựa đầu tiên. Bởi vì, không có nghiên cứu nào về thuốc được tiến hành trên bệnh nhân BCTPĐ đã được đặt ICD với mục tiêu phòng ngừa ICD sốc. Vì vậy, khuyến cáo được suy ra từ nghiên cứu trên nhiều bệnh khác nhau. Trong nghiên cứu OPTIC (Optimal Pharmacological Therapy in Cardioverter Defibrillator Patients) với 412 bệnh nhân đã được đặt ICD điều trị thuốc chẹn beta, sotalol đơn độc, hoặc amiodarone kết hợp thuốc chẹn beta. Sau 1 năm, ICD sốc xảy ra ở 38,5% bệnh nhân dùng thuốc chẹn beta, 24,3% bệnh nhân dùng sotalol đơn độc, 10,3% bệnh nhân dùng amiodarone kết hợp thuốc chẹn beta(197). Như vậy, amiodarone hết hợp với chẹn beta hiệu quả nhất nhưng tăng tác dụng phụ(197). Trong một nghiên cứu trên 30 bệnh nhân được đặt ICD phòng ngừa thứ phát nhịp nhanh thất và rung thất, dofetilide đã chứng minh làm giảm tần suất nhịp nhanh thất / rung thất và ICD sốc khi những thuốc chống loạn nhịp khác, kể cả amiodarone, không hiệu quả(199). Mexiletine được thêm vào khi amiodarone không hiệu quả, làm giảm nhịp nhanh thất, rung thất ở bệnh nhân đã được đặt ICD(200). Phân tích tổng hợp trên 2268 bệnh nhân thể hiện thuốc chống loạn nhịp (chủ yếu là amiodarone) làm giảm ICD sốc không thích hợp, tuy không có lợi trên tỷ lệ sống còn(198). Hiệu quả và sự an toàn của các thuốc trong khuyến cáo loại 1 bao gồm propafenone và flecaine là không chắc chắn.

Ở trẻ em mắc BCTPĐ có nhịp nhanh thất tái phát, thuốc chẹn beta thường là chọn lựa hàng đầu. Dữ liệu về các biện pháp điều trị thay thế khi ICD sốc nhiều lần dù đã dùng thuốc tối đa như triệt đốt qua đường ống thông còn hạn chế. Cắt giao cảm mới chỉ báo cáo dưới dạng từng ca(208).

Điều trị bằng ICD đã được chứng minh giúp phòng ngừa đột tử và cải thiện tỷ lệ sống còn ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ(209). Rối loạn nhịp thất có thể kết thúc bằng tạo nhịp nhanh, bao gồm nhịp nhanh thất đơn dạng và cuồng thất. Một nghiên cứu với 71 bệnh nhân BCTPĐ được đặt ICD, có 149 rối loạn nhịp được ghi nhận; trong đó rung thất hiện diện 74 lần, nhanh thất 57 lần và cuồng thất 18 lần và tạo nhịp nhanh thành công trong 74% các cơn(201). Điều này đặc biệt quan trọng đối với những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ nhịp nhanh thất đơn dạng như phình mỏm.

Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rối loạn nhịp thất tái phát, dù đã được điều trị bằng thuốc, cắt đốt được chứng minh là có lợi. Tỷ lệ thành công được ghi nhận là 73% không biến chứng(201). Trong một báo cáo loạt ca, phẫu thuật cắt túi phình mỏm thất trái ở ba bệnh nhân phình mỏm thất trái và nhịp nhanh thất kéo dài là biện pháp thay thế cắt đốt(210). Hủy giao cảm tim trái có hiệu quả đã được báo cáo ở vài trường hợp nhịp nhanh thất / rung thất trơ(210).

6.5 Điều trị bệnh nhân BCTPĐ suy tim rất nặng (Advanced Heart Failure)

| Loại | MCC | Khuyến cáo điều trị bệnh nhân BCTPĐ suy tim rất nặng |

| 1 | C | 1. Ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rối loạn chức năng tâm thu với phân suất tống máu thất trái dưới 50%, điều trị theo khuyến cáo suy tim với phân suất tống máu giảm(74,120,211). |

| 1 | C | 2. Ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rối loạn chức năng tâm thu, trắc nghiệm chẩn đoán đánh giá nguyên nhân đồng mắc gây rối loạn chức năng tâm thu (như bệnh động mạch vành) nên được thực hiện(212–214). |

| 1 | B | 3. Ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ không tắc nghẽn và suy tim rất nặng (NYHA III – NYHA IV dù đã được điều trị theo khuyến cáo), CPET nên được thực hiện để định lượng mức độ giới hạn chức năng và hỗ trợ trong việc chọn lựa bệnh nhân ghép tim hoặc hỗ trợ tuần hoàn cơ học(215,216). |

| 1 | B | 4. Ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ không tắc nghẽn và suy tim rất nặng (NYHA III – NYHA IV dù đã được điều trị theo khuyến cáo) hoặc có rối loạn nhịp thất đe dọa tính mạng không đáp ứng với điều trị tối đa theo khuyến cáo, đánh giá ghép tim theo danh sách tiêu chí nên được thực hiện(195,217). |

| 2a | C | 5. Đối với những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có rối loạn chức năng tâm thu (PSTM thất trái dưới 50%), ngưng thuốc làm giảm sức co bóp cơ tim đang dùng là hợp lý (đặc biệt là verapamil, diltiazem, hoặc disopyramide). |

| 2a | B | 6. Ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ không tắc nghẽn và suy tim rất nặng (NYHA III – NYHA IV dù đã được điều trị nội khoa tối ưu theo khuyến cáo) là ứng cử viên của ghép tim, điều trị dụng cụ hỗ trợ thất trái (LVAD) dòng liên tục là hợp lý trong khi chờ đợi ghép tim(218). |

| 2a | C | 7. Ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có PSTM thất trái dưới 50%, đặt ICD là có lợi. |

| 2a | C | 8. Ở những bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có PSTM thất trái dưới 50%, (NYHA III – NYHA IV dù đã được điều trị theo khuyến cáo và blốc nhánh trái , CRT có thể có lợi nhằm cải thiện triệu chứng (121,219–222). |

| CPET, Cardio Pulmonary Exercise Test, Nghiệm pháp gắng sức tim phổi; LVAD, Dụng cụ hỗ trợ thất trái, Left Ventricular Assist Device; CRT, Cardiac Resynchronization, Điều trị tái đồng bộ tim. | ||

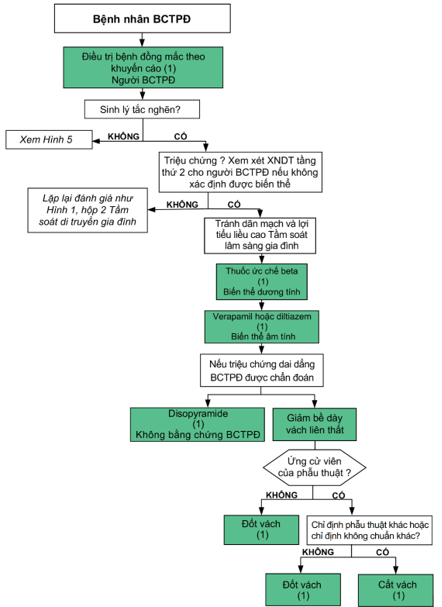

Hình 4. Điều trị triệu chứng bệnh nhân BCTPĐ

BCTPĐ, bệnh cơ tim phì đại; XNDT, xét nghiệm di truyền

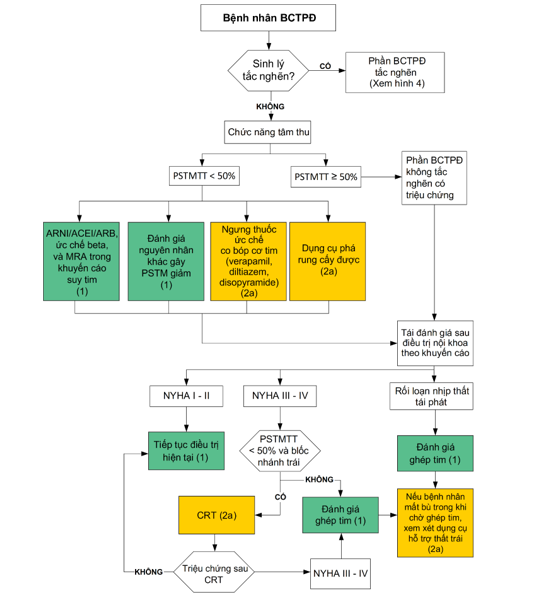

Hình 5. Sơ đồ điều trị suy tim

ARNI, Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin inhibitors, Ức chế thụ thể angiotensin receptor-neprilysin; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker, Ức chế thụ thể angiotensin; CRT, Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy, Điều trị tái đồng bộ tim; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, Kháng thụ thể mineralocorticoid; PSTM, Phân suất tống máu; PSTMTT, Phân suất tống máu thất trái.

Tiếp cận chung trong điều trị suy tim được trình bày trong Hình 2 và Hình 3. Trong BCTPĐ, phân suất tống máu dưới 50% thường liên quan đến những kết cục xấu; vì vậy, tình huống này được xem là chức năng tâm thu giảm quan trọng. Do đó, ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ, việc điều trị theo khuyến cáo suy tim phân suất giảm được áp dụng khi phân suất tống máu dưới 50% (dưới 40% đối với các nguyên nhân suy tim khác)(74,120). ICD giúp phòng ngừa đột tử tiên phát. CRT ở bệnh nhân có phân suất tống máu dưới 50% và NYHA III – IV kèm các tiêu chí thỏa điều kiện đặt CRT(120). Bất kể phân suất tống máu là bao nhiêu, nếu bệnh nhân có rối loạn nhịp thất tái phát hoặc có NYHA III – IV dù đã điều trị nội khoa tối ưu và điều trị giảm bề dày vách thất không được lựa chọn, đánh giá ghép tim nên được tiến hành với phân tầng nguy cơ với CPET. Đôi khi bệnh nhân NYHA III – IV cần dùng dụng cụ hỗ trợ thất trái.

Nhiều nghiên cứu cho thấy bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có phân suất tống máu dưới 50% có tiên lượng sống còn xấu hơn BCTPĐ có phân suất tống máu bảo tồn(74,211,223). Mặc dù bệnh nhân BCTPĐ bị loại trừ khỏi các thử nghiệm lâm sàng ngẫu nhiên có đối chứngtrong suy tim, việc điều trị suy tim bệnh nhân BCTPĐ có phân suất tống máu giảm vẫn có thể tuân theo khuyến cáo(120,166,224). Vì BCTPĐ có phân suất tống máu giảm chỉ chiếm khoảng 5% nên việc đánh giá các nguyên nhân gây phân suất tống máu giảm khác nên được thực hiện bao gồm bệnh động mạch vành, bệnh van tim, các rối loạn chuyển hóa. Các thuốc làm giảm sức co bóp cơ tim như verapamil, diltiazem, disopyramide có thể ngưng nếu triệu chứng suy tim nặng hơn.

Bệnh nhân BCTPĐ thường không phải là ứng cử viên lý tưởng cho dụng cụ hỗ trợ thất trái vì buồng thất trái nhỏ và phân suất tống máu bảo tốn. Tuy nhiên, vài trường hợp được báo cáo với kết quả chấp nhận được với dụng cụ hỗ trợ thất trái dòng liên tục (218,225–227) và tỷ lệ sống còn tốt hơn sau dụng cụ hỗ trợ thất trái ở bệnh nhân có đường kính buồng thất trái lớn hơn (46 – 50 mm)(225,227). Dữ liệu liên quan đến hỗ trợ hai thất còn hạn chế.

Dự phòng đột tử tiên phát với ICD khi phân suất tống máu dưới 50% đã được chấp thuận(120). Ở bệnh nhân BCTPĐ trẻ em, việc đặt ICD cần được cân nhắc kỹ vì kích thước ICD và nguy cơ của dụng cụ này.

CRT đã được chứng minh có lợi về tỷ lệ sống còn và tỷ lệ tái nhập viện vì suy tim ở bệnh nhân suy tim với phân suất tống máu giảm và blốc nhánh trái với QRS ≥ 150 ms(120). Tuy nhiên, lợi ích của CRT trên bệnh nhân BCTPĐ chưa được chứng minh.

CPET hữu ích trong đánh giá chức năng hệ tim mạch, phổi và cơ xương ở bệnh nhân suy tim cần xét chỉ định ghép tim(215,216). Tiêu chí chọn bệnh ghép dựa theo khuyến cáo hiện tại(207). Khác với BCTDN, ghép tim trong BCTPĐ không chỉ ở giai đoạn phân suất tống máu giảm, ghép tim có thể được chỉ định ở BCTPĐ có phân suất tống máu bảo tồn.

Xem tiếp kỳ sau…

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

- Geske JB, Ommen SR, Gersh BJ. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Clinical Update. JACC: Heart Failure. 2018;6(5):364-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCHF.2018.02.010

- Marian AJ, Braunwald E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research. 2017;121(7):749-770. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311059

- Maron BJ, Ommen SR, Semsarian C, Spirito P, Olivotto I, Maron MS. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Present and Future, With Translation Into Contemporary Cardiovascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(1):83-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2014.05.003

- Maron BJ. Clinical Course and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(7):655-668. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMRA1710575

- Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New Perspectives on the Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2015.01.019

- Maron M, Hellawell J, cardiology JL… journal of, 2016 undefined. Occurrence of clinically diagnosed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the United States. Elsevier. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002914916303046

- Burke MA, Cook SA, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Clinical and Mechanistic Insights Into the Genetics of Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(25):2871-2886. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2016.08.079

- Ingles J, Burns C, Bagnall RD, et al. Nonfamilial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2017;10(2). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001620

- Ho CY, Day SM, Ashley EA, et al. Genotype and lifetime burden of disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy insights from the sarcomeric human cardiomyopathy registry (SHaRe). Circulation. 2018;138(14):1387-1398. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033200

- Maron B, Rowin E, Casey S, cardiology MMJ, 2016 undefined. How hypertrophic cardiomyopathy became a contemporary treatable genetic disease with low mortality: shaped by 50 years of clinical research and practice. jamanetwork.com. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/article-abstract/2498963

- Maron MS, Olivotto I, Zenovich AG, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly a disease of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2006;114(21):2232-2239. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644682

- Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Gersh BJ, et al. Outcome of Mildly Symptomatic or Asymptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. A Long-Term Follow-Up Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(3):234-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2009.01.079

- Pellikka PA, Oh JK, Bailey KR, Nichols BA, Monahan KH, Tajik AJ. Dynamic intraventricular obstruction during dobutamine stress echocardiography: A new observation. Circulation. 1992;86(5):1429-1432. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.86.5.1429

- Villemain O, Correia M, Mousseaux E, et al. Myocardial Stiffness Evaluation Using Noninvasive Shear Wave Imaging in Healthy and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathic Adults. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2019;12(7):1135-1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2018.02.002

- Paulus WJ, Lorell BH, Craig WE, Wynne J, Murgo JP, Grossman W. Comparison of the effects of nitroprusside and nifedipine on diastolic properties in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Altered left ventricular loading or improved muscle inactivation? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;2(5):879-886. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(83)80235-6

- Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2014;130(6):484-495. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007094

- Sherrid M v., Balaram S, Kim B, Axel L, Swistel DG. The Mitral Valve in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Test in Context. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(15):1846-1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2016.01.071

- Maron MS, Olivotto I, Harrigan C, et al. Mitral valve abnormalities identified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance represent a primary phenotypic expression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2011;124(1):40-47. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985812

- Hodges K, Rivas CG, Aguilera J, et al. Surgical management of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in a specialized hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy center. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2019;157(6):2289-2299. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTCVS.2018.11.148

- Hong JH, Schaff H v., Nishimura RA, et al. Mitral Regurgitation in Patients With Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy: Implications for Concomitant Valve Procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(14):1497-1504. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2016.07.735

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy With Left Ventricular Apical Aneurysm: Implications for Risk Stratification and Management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(7):761-773. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2016.11.063

- Patel V, Critoph CH, Finlay MC, Mist B, Lambiase PD, Elliott PM. Heart Rate Recovery in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2014;113(6):1011-1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2013.11.062

- Olivotto I, Maron BJ, Montereggi A, Mazzuoli F, Dolara A, Cecchi F. Prognostic value of systemic blood pressure response during exercise in a community-based patient population with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(7):2044-2051. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00094-7

- Frenneaux MP, Counihan PJ, Caforio ALP, Chikamori T, McKenna WJ. Abnormal blood pressure response during exercise in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1990;82(6):1995-2002. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.82.6.1995

- Sadoul N, Prasad K, Elliott PM, Bannerjee S, Frenneaux MP, McKenna WJ. Prospective Prognostic Assessment of Blood Pressure Response During Exercise in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997;96(9):2987-2991. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.96.9.2987

- Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2020;142(25):e558-e631. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000937

- Ahmad F, McNally EM, Ackerman MJ, et al. Establishment of Specialized Clinical Cardiovascular Genetics Programs: Recognizing the Need and Meeting Standards: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019;12(6):286-305. https://doi.org/10.1161/HCG.0000000000000054

- Charron P, Arad M, Arbustini E, et al. Genetic counselling and testing in cardiomyopathies: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(22):2715-2728. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHQ271

- Maron BJ, Maron MS, Semsarian C. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 20 years: clinical perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(8):705-715. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2012.02.068

- Ingles J, Sarina T, Yeates L, et al. Clinical predictors of genetic testing outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genet Med. 2013;15(12):972-977. https://doi.org/10.1038/GIM.2013.44

- van Velzen HG, Schinkel AFL, Baart SJ, et al. Outcomes of Contemporary Family Screening in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11(4):e001896. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGEN.117.001896

- Ranthe MF, Carstensen L, Øyen N, et al. Risk of Cardiomyopathy in Younger Persons With a Family History of Death from Cardiomyopathy: A Nationwide Family Study in a Cohort of 3.9 Million Persons. Circulation. 2015;132(11):1013-1019. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013478

- Lafreniere-Roula M, Bolkier Y, Zahavich L, et al. Family screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Is it time to change practice guidelines? Eur Heart J. 2019;40(45):3672-3681. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHZ396

- Alfares AA, Kelly MA, McDermott G, et al. Results of clinical genetic testing of 2,912 probands with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: expanded panels offer limited additional sensitivity. Genet Med. 2015;17(11):880-888. https://doi.org/10.1038/GIM.2014.205

- Bagnall RD, Ingles J, Dinger ME, et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Improves Outcomes of Genetic Testing in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):419-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2018.04.078

- Ingles J, Burns C, Funke B. Pathogenicity of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Variants. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2017;10(5). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001916

- Maron BJ, Roberts WC, Arad M, et al. Clinical outcome and phenotypic expression in LAMP2 cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1253-1259. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2009.371

- Desai MY, Ommen SR, McKenna WJ, Lever HM, Elliott PM. Imaging phenotype versus genotype in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(2):156-168. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.957936

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-424. https://doi.org/10.1038/GIM.2015.30

- Ouellette AC, Mathew J, Manickaraj AK, et al. Clinical genetic testing in pediatric cardiomyopathy: Is bigger better? Clin Genet. 2018;93(1):33-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/CGE.13024

- Jensen MK, Havndrup O, Christiansen M, et al. Penetrance of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in children and adolescents: a 12-year follow-up study of clinical screening and predictive genetic testing. Circulation. 2013;127(1):48-54. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.090514

- Semsarian C, Ingles J, Wilde AAM. Sudden cardiac death in the young: the molecular autopsy and a practical approach to surviving relatives. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(21):1290-1296. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHV063

- Bagnall RD, Weintraub RG, Ingles J, et al. A prospective study of sudden cardiac death among children and young adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(25):2441-2452.

- Jipin Das K, Ingles J, Bagnall RD, Semsarian C. Determining pathogenicity of genetic variants in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: importance of periodic reassessment. Genet Med. 2014;16(4):286-293. https://doi.org/10.1038/GIM.2013.138

- Manrai AK, Funke BH, Rehm HL, et al. Genetic Misdiagnoses and the Potential for Health Disparities. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(7):655-665. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMSA1507092

- Mathew J, Zahavich L, Lafreniere-Roula M, et al. Utility of genetics for risk stratification in pediatric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Genet. 2018;93(2):310-319. https://doi.org/10.1111/CGE.13157

- Ingles J, Doolan A, Chiu C, Seidman J, Seidman C, Semsarian C. Compound and double mutations in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: implications for genetic testing and counselling. J Med Genet. 2005;42(10). https://doi.org/10.1136/JMG.2005.033886

- Aronson SJ, Clark EH, Varugheese M, Baxter S, Babb LJ, Rehm HL. Communicating new knowledge on previously reported genetic variants. Genet Med. 2012;14(8):713-719. https://doi.org/10.1038/GIM.2012.19

- Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2015.01.019

- Ingles J, Goldstein J, Thaxton C, et al. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Genes. Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine. 2019;12(2):57-64. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002460

- Elliott P, Baker R, Pasquale F, et al. Prevalence of Anderson-Fabry disease in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the European Anderson-Fabry Disease survey. Heart. 2011;97(23):1957-1960. https://doi.org/10.1136/HEARTJNL-2011-300364

- Lafreniere-Roula M, Bolkier Y, Zahavich L, et al. Family screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Is it time to change practice guidelines? Eur Heart J. 2019;40(45):3672-3681. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHZ396

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-424. https://doi.org/10.1038/GIM.2015.30

- Watkins H, McKenna WJ, Thierfelder L, et al. Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin T and alpha-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(16):1058-1065. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199504203321603

- Olivotto I, Girolami F, Ackerman MJ, et al. Myofilament protein gene mutation screening and outcome of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(6):630-638. https://doi.org/10.4065/83.6.630

- Captur G, Lopes LR, Mohun TJ, et al. Prediction of sarcomere mutations in subclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(6):863-871. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002411

- Ho CY, Day SM, Colan SD, et al. The Burden of Early Phenotypes and the Influence of Wall Thickness in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Mutation Carriers: Findings From the HCMNet Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(4):419-428. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2016.5670

- Vigneault DM, Yang E, Jensen PJ, et al. Left Ventricular Strain Is Abnormal in Preclinical and Overt Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Cardiac MR Feature Tracking. Radiology. 2019;290(3):640-648. https://doi.org/10.1148/RADIOL.2018180339

- Williams LK, Misurka J, Ho CY, et al. Multilayer Myocardial Mechanics in Genotype-Positive Left Ventricular Hypertrophy-Negative Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(10):1754-1760. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2018.08.008

- Norrish G, Jager J, Field E, et al. Yield of Clinical Screening for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Child First-Degree Relatives. Circulation. 2019;140(3):184-192. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038846

- Christiaans I, Birnie E, Bonsel GJ, et al. Manifest disease, risk factors for sudden cardiac death, and cardiac events in a large nationwide cohort of predictively tested hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation carriers: determining the best cardiological screening strategy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(9):1161-1170. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHR092

- Maurizi N, Michels M, Rowin EJ, et al. Clinical Course and Significance of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Without Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Circulation. 2019;139(6):830-833. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037264

- Vermeer AMC, Clur SAB, Blom NA, Wilde AAM, Christiaans I. Penetrance of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Children Who Are Mutation Positive. J Pediatr. 2017;188:91-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDS.2017.03.033

- Gray B, Ingles J, Semsarian C. Natural history of genotype positive-phenotype negative patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152(2):258-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJCARD.2011.07.095

- Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Wessler BS, et al. Enhanced American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Strategy for Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in High-Risk Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(7):644-657. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2019.1391

- O’Mahony C, Jichi F, Ommen SR, et al. International External Validation Study of the 2014 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on Sudden Cardiac Death Prevention in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (EVIDENCE-HCM). Circulation. 2018;137(10):1015-1023. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030437

- Elliott PM, Sharma S, Varnava A, Poloniecki J, Rowland E, McKenna WJ. Survival after cardiac arrest or sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(6):1596-1601. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00056-X

- Spirito P, Autore C, Rapezzi C, et al. Syncope and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;119(13):1703-1710. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798314

- Bos JM, Maron BJ, Ackerman MJ, et al. Role of family history of sudden death in risk stratification and prevention of sudden death with implantable defibrillators in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(10):1481-1486. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2010.06.077

- Dimitrow PP, Chojnowska L, Rudziński T, et al. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: old risk factors re-assessed in a new model of maximalized follow-up. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(24):3084-3093. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHQ308

- Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, Bernabò P, Bruzzi P, Maron BJ. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(24):1778-1785. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200006153422403

- Autore C, Bernabò P, Barillà CS, Bruzzi P, Spirito P. The prognostic importance of left ventricular outflow obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy varies in relation to the severity of symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(7):1076-1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2004.12.067

- Elliott PM, Gimeno Blanes JR, Mahon NG, Poloniecki JD, McKenna WJ. Relation between severity of left-ventricular hypertrophy and prognosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2001;357(9254):420-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04005-8

- Harris KM, Spirito P, Maron MS, et al. Prevalence, clinical profile, and significance of left ventricular remodeling in the end-stage phase of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;114(3):216-225. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583500

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy With Left Ventricular Apical Aneurysm: Implications for Risk Stratification and Management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(7):761-773. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2016.11.063

- Ichida M, Nishimura Y, Kario K. Clinical significance of left ventricular apical aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients: the role of diagnostic electrocardiography. J Cardiol. 2014;64(4):265-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JJCC.2014.02.011

- Monserrat L, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Sharma S, Penas-Lado M, McKenna WJ. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an independent marker of sudden death risk in young patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(5):873-879. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00827-1

- Wang W, Lian Z, Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Maron MS, Link MS. Prognostic Implications of Nonsustained Ventricular Tachycardia in High-Risk Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10(3). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004604

- Corona-Villalobos CP, Sorensen LL, Pozios I, et al. Left ventricular wall thickness in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a comparison between cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32(6):945-954. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10554-016-0858-4

- Bois JP, Geske JB, Foley TA, Ommen SR, Pellikka PA. Comparison of Maximal Wall Thickness in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Differs Between Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Transthoracic Echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119(4):643-650. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2016.11.010

- Maron MS, Lesser JR, Maron BJ. Management implications of massive left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy significantly underestimated by echocardiography but identified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(12):1842-1843. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2010.01.367

- Weng Z, Yao J, Chan RH, et al. Prognostic Value of LGE-CMR in HCM: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(12):1392-1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2016.02.031

- Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2014;130(6):484-495. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007094

- Mentias A, Raeisi-Giglou P, Smedira NG, et al. Late Gadolinium Enhancement in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Preserved Systolic Function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(8):857-870. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2018.05.060

- Ismail TF, Jabbour A, Gulati A, et al. Role of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the risk stratification of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2014;100(23):1851-1858. https://doi.org/10.1136/HEARTJNL-2013-305471

- O’Mahony C, Jichi F, Pavlou M, et al. A novel clinical risk prediction model for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM risk-SCD). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(30):2010-2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHT439

- Binder J, Attenhofer Jost CH, Klarich KW, et al. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: prevalence and correlates of apical outpouching. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24(7):775-781. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECHO.2011.03.002

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Carrick RT, et al. Outcomes in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(24):3033-3043. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2020.04.045

- Marstrand P, Han L, Day SM, et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy With Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction: Insights From the SHaRe Registry. Circulation. 2020;141(17):1371-1383. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044366

- Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2014;130(6):484-495. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007094

- Östman-Smith I, Wettrell G, Keeton B, et al. Age- and gender-specific mortality rates in childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(9):1160-1167. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHN122

- Miron A, Lafreniere-Roula M, Steve Fan CP, et al. A Validated Model for Sudden Cardiac Death Risk Prediction in Pediatric Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;142(3):217-229. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047235

- Norrish G, Ding T, Field E, et al. Development of a Novel Risk Prediction Model for Sudden Cardiac Death in Childhood Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM Risk-Kids). JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(9):918-927. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2019.2861

- Wells S, Rowin EJ, Bhatt V, Maron MS, Maron BJ. Association Between Race and Clinical Profile of Patients Referred for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018;137(18):1973-1975. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032838

- Norrish G, Cantarutti N, Pissaridou E, et al. Risk factors for sudden cardiac death in childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(11):1220-1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317702519

- Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Adulthood Associated With Low Cardiovascular Mortality With Contemporary Management Strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(18):1915-1928. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2015.02.061

- Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, et al. Risk stratification and outcome of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy >=60 years of age. Circulation. 2013;127(5):585-593. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.136085

- Norrish G, Ding T, Field E, et al. A validation study of the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for risk stratification of sudden cardiac death in childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2019;21(10):1559-1565. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUZ118

- Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Associated With Low Cardiovascular Mortality With Contemporary Management Strategies. Circulation. 2016;133(1):62-73. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017633

- Rowin EJ, Sridharan A, Madias C, et al. Prediction and Prevention of Sudden Death in Young Patients (. Am J Cardiol. 2020;128:75-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2020.04.042

- O’Mahony C, Tome-Esteban M, Lambiase PD, et al. A validation study of the 2003 American College of Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology and 2011 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association risk stratification and treatment algorithms for sudden cardiac death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2013;99(8):534-541. https://doi.org/10.1136/HEARTJNL-2012-303271

- Vriesendorp PA, Schinkel AFL, van Cleemput J, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: patient outcomes, rate of appropriate and inappropriate interventions, and complications. 2013;166(3):496-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AHJ.2013.06.009

- Maron BJ, Spirito P, Shen WK, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2007;298(4):405-412. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.298.4.405

- Balaji S, DiLorenzo MP, Fish FA, et al. Risk factors for lethal arrhythmic events in children and adolescents with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and an implantable defibrillator: an international multicenter study. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(10):1462-1467.

- Decker JA, Rossano JW, Smith EO, et al. Risk factors and mode of death in isolated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(3):250-254.

- Kamp AN, von Bergen NH, Henrikson CA, et al. Implanted defibrillators in young hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients: a multicenter study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34(7):1620-1627.

- Smith BM, Dorfman AL, Yu S, et al. Clinical significance of late gadolinium enhancement in patients< 20 years of age with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2014;113(7):1234-1239.

- Raja AA, Farhad H, Valente AM, et al. Prevalence and progression of late gadolinium enhancement in children and adolescents with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018;138(8):782-792. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032966

- Maron BJ, Spirito P, Shen WK, et al. Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators and Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2007;298(4):405-412. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.298.4.405

- Vriesendorp PA, Schinkel AFL, van Cleemput J, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Patient outcomes, rate of appropriate and inappropriate interventions, and complications. American Heart Journal. 2013;166(3):496-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AHJ.2013.06.009

- Lampert R, Olshansky B, Heidbuchel H, et al. Safety of sports for athletes with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: Results of a prospective, multinational registry. Circulation. 2013;127(20):2021-2030. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000447

- Okamura H, Friedman PA, Inoue Y, et al. Single-Coil Defibrillator Leads Yield Satisfactory Defibrillation Safety Margin in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation Journal. 2016;80(10):CJ-16-0428. https://doi.org/10.1253/CIRCJ.CJ-16-0428

- Killu AM, Park JY, Sara JD, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with end-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. EP Europace. 2018;20(1):82-88. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUW327

- Gu M, Jin H, Hua W, et al. Clinical outcome of cardiac resynchronization therapy in dilated-phase hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology : JGC. 2017;14(4):238. https://doi.org/10.11909/J.ISSN.1671-5411.2017.04.002

- Rogers DPS, Marazia S, Chow AW, et al. Effect of biventricular pacing on symptoms and cardiac remodelling in patients with end-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(5):507-513. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJHEART.2008.03.006

- Maron BJ, Spirito P, Ackerman MJ, et al. Prevention of sudden cardiac death with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in children and adolescents with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(14):1527-1535.

- Bettin M, Larbig R, Rath B, et al. Long-Term Experience With the Subcutaneous Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator in Teenagers and Young Adults. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3(13):1499-1506. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACEP.2017.08.017

- Silvetti MS, Pazzano V, Verticelli L, et al. Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: is it ready for use in children and young adults? A single-centre study. Europace. 2018;20(12):1966-1973. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUY139

- Pettit SJ, McLean A, Colquhoun I, Connelly D, McLeod K. Clinical experience of subcutaneous and transvenous implantable cardioverter defibrillators in children and teenagers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36(12):1532-1538. https://doi.org/10.1111/PACE.12233

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0B013E31829E8776

- Rowin EJ, Mohanty S, Madias C, Maron BJ, Maron MS. Benefit of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy in End-Stage Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5(1):131-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACEP.2018.08.018

- Cappelli F, Morini S, Pieragnoli P, et al. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy for End-Stage Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The Need for Disease-Specific Criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(4):464-466. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2017.11.040

- Friedman PA, McClelland RL, Bamlet WR, et al. Dual-chamber versus single-chamber detection enhancements for implantable defibrillator rhythm diagnosis: the detect supraventricular tachycardia study. Circulation. 2006;113(25):2871-2879. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594531

- Theuns DAMJ, Klootwijk APJ, Goedhart DM, Jordaens LJLM. Prevention of inappropriate therapy in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results of a prospective, randomized study of tachyarrhythmia detection algorithms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(12):2362-2367. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2004.09.039

- Kolb C, Sturmer M, Sick P, et al. Reduced risk for inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks with dual-chamber therapy compared with single-chamber therapy: results of the randomized OPTION study. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(6):611-619. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCHF.2014.05.015

- Peterson PN, Greenlee RT, Go AS, et al. Comparison of Inappropriate Shocks and Other Health Outcomes Between Single- and Dual-Chamber Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators for Primary Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: Results From the Cardiovascular Research Network Longitudinal Study of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(11). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006937

- Defaye P, Boveda S, Klug D, et al. Dual- vs. single-chamber defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death: long-term follow-up of the Défibrillateur Automatique Implantable-Prévention Primaire registry. Europace. 2017;19(9):1478-1484. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUW230

- Hu ZY, Zhang J, Xu ZT, et al. Efficiencies and Complications of Dual Chamber versus Single Chamber Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators in Secondary Sudden Cardiac Death Prevention: A Meta-analysis. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25(2):148-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HLC.2015.07.008

- COHEN LS, BRAUNWALD E. Amelioration of angina pectoris in idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis with beta-adrenergic blockade. Circulation. 1967;35(5):847-851.

- Adelman AG, Shah PM, Gramiak R, Wigle ED. Long-term propranolol therapy in muscular subaortic stenosis. Heart. 1970;32(6):804-811.

- Stenson RE, Flamm Jr MD, Harrison DC, Hancock EW. Hypertrophic subaortic stenosis: clinical and hemodynamic effects of long-term propranolol therapy. Am J Cardiol. 1973;31(6):763-773.

- Bonow RO, Rosing DR, Bacharach SL, et al. Effects of verapamil on left ventricular systolic function and diastolic filling in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1981;64(4):787-796. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.64.4.787

- TOSHIMA H, KOGA Y, NAGATA H, TOYOMASU K, ITAYA K ichi, MATOBA T. Comparable Effects of Oral Diltiazem and Verapamil in the Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Double-blind Crossover Study. Jpn Heart J. 1986;27(5):701-715.

- Rosing DR, Kent KM, Maron BJ, Epstein SE. Verapamil Therapy: A New Approach to the Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy II. Effects on Exercise Capacity and Symptomatic Status. Accessed May 16, 2022. http://ahajournals.org

- Sherrid M v, Barac I, McKenna WJ, et al. Multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of disopyramide in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(8):1251-1258.

- Sherrid M v, Shetty A, Winson G, et al. Treatment of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy symptoms and gradient resistant to first-line therapy with β-blockade or verapamil. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2013;6(4):694-702.

- Adler A, Fourey D, Weissler‐Snir A, et al. Safety of outpatient initiation of disopyramide for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6):e005152.

- Maron BJ, Dearani JA, Ommen SR, et al. Low operative mortality achieved with surgical septal myectomy: role of dedicated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy centers in the management of dynamic subaortic obstruction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1307-1308.

- Ommen SR, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Long-term effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(3):470-476.

- Braunwald E, Ebert PA. Hemodynamic alterations in idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis induced by sympathomimetic drugs∗. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1962;10(4):489-495. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(62)90373-9

- Maron MS, Olivotto I, Zenovich AG, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly a disease of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2006;114(21):2232-2239.

- Kirk CR, Gibbs JL, Thomas R, Radley-Smith R, Qureshi SA. Cardiovascular collapse after verapamil in supraventricular tachycardia. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62(12):1265-1266.

- Moran AM, Colan SD. Verapamil therapy in infants with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Young. 1998;8(3):310-319.

- Florian Rader. EXPLORER-LTE cohort of the MAVA-LTE extension study . In: Presented at: ACC April 3. ACC; 2022.

- Florian Rader. EXPLORER-HCM Presented at the American College of Cardiology Annual Scientific Session (ACC 2022). In: Presented at: ACC April 3. ; 2022.

- VALOR-HCM: Mavacamten Significantly Reduces Need For Surgical Intervention in Patients With Obstructive HCM – American College of Cardiology. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2022/03/31/20/23/Sat-930am-VALOR-HCM-acc-2022

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Lesser JR, Rastegar H, Maron MS. Papillary muscle insertion directly into the anterior mitral leaflet in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, its identification and cause of outflow obstruction by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and its surgical management. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(11):1677-1679. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2013.01.340

- di Tommaso L, Stassano P, Mannacio V, et al. Asymmetric septal hypertrophy in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the usefulness of associated septal myectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(1):171-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTCVS.2011.10.096

- Teo EP, Teoh JG, Hung J. Mitral valve and papillary muscle abnormalities in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2015;30(5):475-482. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000200

- Batzner A, Pfeiffer B, Neugebauer A, Aicha D, Blank C, Seggewiss H. Survival After Alcohol Septal Ablation in Patients With Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):3087-3094. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2018.09.064

- Nguyen A, Schaff H v., Hang D, et al. Surgical myectomy versus alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A propensity score-matched cohort. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(1):306-315.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTCVS.2018.08.062

- Kimmelstiel C, Zisa DC, Kuttab JS, et al. Guideline-Based Referral for Septal Reduction Therapy in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Is Associated With Excellent Clinical Outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(7). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007673

- Mitra A, Ghosh RK, Bandyopadhyay D, Ghosh GC, Kalra A, Lavie CJ. Significance of Pulmonary Hypertension in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2020;45(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPCARDIOL.2018.10.002

- Ong KC, Geske JB, Hebl VB, et al. Pulmonary hypertension is associated with worse survival in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. European heart journal Cardiovascular Imaging. 2016;17(6):604-610. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEW024

- Desai MY, Bhonsale A, Patel P, et al. Exercise echocardiography in asymptomatic HCM: Exercise capacity, and not LV outflow tract gradient predicts long-term outcomes. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2014;7(1):26-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2013.08.010

- Nguyen A, Schaff H v., Nishimura RA, et al. Determinants of Reverse Remodeling of the Left Atrium After Transaortic Myectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106(2):447-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHORACSUR.2018.03.039

- Finocchiaro G, Haddad F, Kobayashi Y, et al. Impact of Septal Reduction on Left Atrial Size and Diastole in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography. 2016;33(5):686-694. https://doi.org/10.1111/ECHO.13158

- Blackshear JL, Kusumoto H, Safford RE, et al. Usefulness of Von Willebrand Factor Activity Indexes to Predict Therapeutic Response in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(3):436-442. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2015.11.016

- Blackshear JL, Stark ME, Agnew RC, et al. Remission of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding after septal reduction therapy in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy-associated acquired von Willebrand syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(2):191-196. https://doi.org/10.1111/JTH.12780

- Desai MY, Smedira NG, Dhillon A, et al. Prediction of sudden death risk in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Potential for refinement of current criteria. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156(2):750-759.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTCVS.2018.03.150

- McLeod CJ, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ, et al. Surgical septal myectomy decreases the risk for appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator discharge in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(21):2583-2588. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHM117

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(25):e1159-e1195. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000503

- Kim LK, Swaminathan R v., Looser P, et al. Hospital Volume Outcomes After Septal Myectomy and Alcohol Septal Ablation for Treatment of Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: US Nationwide Inpatient Database, 2003-2011. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(3):324-332. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2016.0252

- Pelliccia F, Pasceri V, Limongelli G, … CAI journal of, 2017 undefined. Long-term outcome of nonobstructive versus obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Elsevier. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016752731730726X

- Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoraci. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(25):e212-e260. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2011.06.011

- Yancy CW, Mariell Jessup C, Chair Biykem Bozkurt V, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):776-803. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2017.04.025

- Spoladore R, Maron MS, D’Amato R, Camici PG, Olivotto I. Pharmacological treatment options for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: high time for evidence. European Heart Journal. 2012;33(14):1724-1733. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHS150

- Axelsson A, Iversen K, Vejlstrup N, et al. Efficacy and safety of the angiotensin II receptor blocker losartan for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the INHERIT randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(2):123-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70241-4

- Nguyen A, Schaff H v., Nishimura RA, et al. Apical myectomy for patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and advanced heart failure. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2020;159(1):145-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTCVS.2019.03.088

- Bourmayan C, Razavi A, Fournier C, et al. Effect of propranolol on left ventricular relaxation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An echographic study. American Heart Journal. 1985;109(6):1311-1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8703(85)90357-6

- Alvares RF, Goodwin JF. Non-invasive assessment of diastolic function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy on and off beta adrenergic blocking drugs. Br Heart J. 1982;48(3):204-212. https://doi.org/10.1136/HRT.48.3.204

- Wilmshurst PT, Thompson DS, Juul SM, Jenkins BS, Webb-Peploe MM. Effects of verapamil on haemodynamic function and myocardial metabolism in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Br Heart J. 1986;56(6):544-553. https://doi.org/10.1136/HRT.56.6.544

- Udelson JE, Bonow RO, O’Gara PT, et al. Verapamil prevents silent myocardial perfusion abnormalities during exercise in asymptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1989;79(5):1052-1060. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.79.5.1052

- Pacileo G, de Cristofaro M, Russo MG, Sarubbi B, Pisacane C, Calabrò R. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in pediatric patients: effect of verapamil on regional and global left ventricular diastolic function. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2000;16(2):146-152.

- Guttmann OP, Pavlou M, O’Mahony C, et al. Prediction of thrombo-embolic risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM Risk-CVA). Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(8):837-845. https://doi.org/10.1002/EJHF.316

- Jung H, Yang PS, Jang E, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Chest. 2019;155(2):354-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHEST.2018.11.009

- Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Shah ND, Gersh BJ. Stroke and Bleeding Risks in NOAC- and Warfarin-Treated Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(25):3020-3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2016.04.026

- Dominguez F, Climent V, Zorio E, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2017;248:232-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJCARD.2017.08.010

- Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(4):e136-e221. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HRTHM.2015.09.019

- Wilke I, Witzel K, MÜnch J, et al. High Incidence of De Novo and Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Cardiac Rhythm Management Device. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27(7):779-784. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCE.12982

- Mahajan R, Perera T, Elliott AD, et al. Subclinical device-detected atrial fibrillation and stroke risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(16):1407-1415. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHX731

- Rowin EJ, Hausvater A, Link MS, et al. Clinical Profile and Consequences of Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2017;136(25):2420-2436. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029267

- Tanel RE, Walsh EP, Lulu JA, Saul JP. Sotalol for refractory arrhythmias in pediatric and young adult patients: initial efficacy and long-term outcome. Am Heart J. 1995;130(4):791-797. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8703(95)90079-9

- Zhao DS, Shen Y, Zhang Q, et al. Outcomes of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2016;18(4):508-520. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUV339

- Lapenna E, Pozzoli A, de Bonis M, et al. Mid-term outcomes of concomitant surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;51(6):1112-1118. https://doi.org/10.1093/EJCTS/EZX017

- Guttmann OP, Rahman MS, O’Mahony C, Anastasakis A, Elliott PM. Atrial fibrillation and thromboembolism in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: systematic review. Heart. 2014;100(6):465-472. https://doi.org/10.1136/HEARTJNL-2013-304276

- Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Shah ND, Gersh BJ. Stroke and Bleeding Risks in NOAC- and Warfarin-Treated Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(25):3020-3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2016.04.026

- Dominguez F, Climent V, Zorio E, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2017;248:232-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJCARD.2017.08.010

- Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Bellone P, et al. Clinical profile of stroke in 900 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(2):301-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01727-2

- van Velzen HG, Theuns DAMJ, Yap SC, Michels M, Schinkel AFL. Incidence of Device-Detected Atrial Fibrillation and Long-Term Outcomes in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119(1):100-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2016.08.092

- Wilke I, Witzel K, MÜnch J, et al. High Incidence of De Novo and Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Cardiac Rhythm Management Device. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27(7):779-784. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCE.12982

- Santangeli P, Biase L di, Themistoclakis S, et al. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: long-term outcomes and mechanisms of arrhythmia recurrence. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6(6):1089-1094. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000339

- Providencia R, Elliott P, Patel K, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2016;102(19):1533-1543. https://doi.org/10.1136/HEARTJNL-2016-309406

- Bogachev-Prokophiev A v., Afanasyev A v., Zheleznev SI, et al. Concomitant ablation for atrial fibrillation during septal myectomy in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(4):1536-1542.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTCVS.2017.08.063

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Abt P, et al. Impact of Advanced Therapies for Improving Survival to Heart Transplant in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2018;121(8):986-996. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2017.12.044

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Kiernan MS, et al. Advanced heart failure with preserved systolic function in nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: under-recognized subset of candidates for heart transplant. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(6):967-975. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001435

- Connolly SJ, Dorian P, Roberts RS, et al. Comparison of beta-blockers, amiodarone plus beta-blockers, or sotalol for prevention of shocks from implantable cardioverter defibrillators: the OPTIC Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;295(2):165-171. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.295.2.165

- Santangeli P, Muser D, Maeda S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antiarrhythmic drugs and catheter ablation for the prevention of recurrent ventricular tachycardia in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(7):1552-1559. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HRTHM.2016.03.004

- Baquero GA, Banchs JE, Depalma S, et al. Dofetilide reduces the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias and implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapies. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23(3):296-301. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-8167.2011.02183.X

- Gao D, van Herendael H, Alshengeiti L, et al. Mexiletine as an adjunctive therapy to amiodarone reduces the frequency of ventricular tachyarrhythmia events in patients with an implantable defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;62(2):199-204. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0B013E31829651FE

- Link MS, Bockstall K, Weinstock J, et al. Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Defibrillators: Triggers, Treatment, and Implications. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28(5):531-537. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCE.13194

- Wilkoff BL, et al. 2015 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on optimal implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming and testing. Europace. 2017;19(4):580. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUW260

- Santangeli P, di Biase L, Lakkireddy D, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: safety and feasibility. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(8):1036-1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HRTHM.2010.05.022

- Igarashi M, Nogami A, Kurosaki K, et al. Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Apical Aneurysm. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology. 2018;4(3):339-350. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACEP.2017.12.020

- Dukkipati SR, D’Avila A, Soejima K, et al. Long-term outcomes of combined epicardial and endocardial ablation of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4(2):185-194. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.110.957290

- Borne RT, Varosy PD, Masoudi FA. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks: epidemiology, outcomes, and therapeutic approaches. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):859-865. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAINTERNMED.2013.428

- Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: A 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(1):1-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HEALUN.2015.10.023

- Raskin JS, Liu JJ, Abrao A, Holste K, Raslan AM, Balaji S. Minimally invasive posterior extrapleural thoracic sympathectomy in children with medically refractory arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(7):1381-1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HRTHM.2016.03.041

- Maron BJ, Shen WK, Link MS, et al. Efficacy of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for the prevention of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(6):365-373. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200002103420601

- Nguyen A, Schaff H v. Electrical storms in patients with apical aneurysms and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: A case series. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154(6):e101-e103. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTCVS.2017.06.002

- Hebl VB, Miranda WR, Ong KC, et al. The Natural History of Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(3):279-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MAYOCP.2016.01.002

- Rowin EJ, Maron MS, Chan RH, et al. Interaction of Adverse Disease Related Pathways in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(12):2256-2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2017.08.048

- Melacini P, Basso C, Angelini A, et al. Clinicopathological profiles of progressive heart failure in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(17):2111-2123. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHQ136

- Pasqualucci D, Fornaro A, Castelli G, et al. Clinical Spectrum, Therapeutic Options, and Outcome of Advanced Heart Failure in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(6):1014-1021. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001843

- Coats CJ, Rantell K, Bartnik A, et al. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing and Prognosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(6):1022-1031. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.002248

- Magrì D, Re F, Limongelli G, et al. Heart Failure Progression in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy – Possible Insights From Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing. Circ J. 2016;80(10):2204-2211. https://doi.org/10.1253/CIRCJ.CJ-16-0432

- Kato TS, Takayama H, Yoshizawa S, et al. Cardiac transplantation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(4):568-574. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2012.04.030

- Topilsky Y, Pereira NL, Shah DK, et al. Left ventricular assist device therapy in patients with restrictive and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):266-275. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959288

- Killu AM, Park JY, Sara JD, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with end-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2018;20(1):82-88. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUW327

- Rogers DPS, Marazia S, Chow AW, et al. Effect of biventricular pacing on symptoms and cardiac remodelling in patients with end-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(5):507-513. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJHEART.2008.03.006

- Gu M, Jin H, Hua W, et al. Clinical outcome of cardiac resynchronization therapy in dilated-phase hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(4):238-244. https://doi.org/10.11909/J.ISSN.1671-5411.2017.04.002

- Cappelli F, Morini S, Pieragnoli P, et al. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy for End-Stage Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The Need for Disease-Specific Criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(4):464-466. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2017.11.040

- Musumeci MB, Russo D, Limite LR, et al. Long-Term Left Ventricular Remodeling of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(11):1924-1931. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2018.08.041

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2016;134(13):e282-e293. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000435

- Grupper A, Park SJ, Pereira NL, et al. Role of ventricular assist therapy for patients with heart failure and restrictive physiology: Improving outcomes for a lethal disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34(8):1042-1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HEALUN.2015.03.012

- Muthiah K, Phan J, Robson D, et al. Centrifugal continuous-flow left ventricular assist device in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a case series. ASAIO J. 2013;59(2):183-187. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0B013E318286018D

- Patel SR, Saeed O, Naftel D, et al. Outcomes of Restrictive and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathies After LVAD: An INTERMACS Analysis. J Card Fail. 2017;23(12):859-867. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARDFAIL.2017.09.011

- Saberi S, Wheeler M, Bragg-Gresham J, et al. Effect of moderate-intensity exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2017;317(13):1349-1357.

- Maron BJ, Levine BD, Washington RL, Baggish AL, Kovacs RJ, Maron MS. Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes with Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Task Force 2: Preparticipation Screening for Cardiovascular Disease in Competitive Athletes: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2015;132(22):e267-e272. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000238

- Turkowski KL, Martijn Bos J, Ackerman NC, Rohatgi RK, Ackerman MJ. Return-to-play for athletes with genetic heart diseases. Circulation. 2018;137(10):1086-1088. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031306

- US Department of Transportation FAAdministration. Medical Certification. Accessed June 25, 2022. https://www.faa.gov/licenses_certificates/medical_certification/

- Bateman BT. What’s New in Obstetric Anesthesia: a focus on maternal morbidity and mortality. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2019;37:68-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJOA.2018.09.004

- Sillesen M, Hjortdal V, Vejlstrup N, Sørensen K. Pregnancy with prosthetic heart valves – 30 years’ nationwide experience in Denmark. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(2):448-454. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJCTS.2010.12.011

- Eleid MF, Konecny T, Orban M, et al. High prevalence of abnormal nocturnal oximetry in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(19):1805-1809. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2009.07.030

- Claes GRF, van Tienen FHJ, Lindsey P, et al. Hypertrophic remodelling in cardiac regulatory myosin light chain (MYL2) founder mutation carriers. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(23):1815-1822. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHV522

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165-3241. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHY340

- Fumagalli C, Maurizi N, Day SM, et al. Association of Obesity With Adverse Long-term Outcomes in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(1):65-72. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2019.4268

- Smith JR, Medina-Inojosa JR, Layrisse V, Ommen SR, Olson TP. Predictors of Exercise Capacity in Patients with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. J Clin Med. 2018;7(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM7110447

- Thaman R, Varnava A, Hamid MS, et al. Pregnancy related complications in women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2003;89(7):752-756. https://doi.org/10.1136/HEART.89.7.752

- Claes GRF, van Tienen FHJ, Lindsey P, et al. Hypertrophic remodelling in cardiac regulatory myosin light chain (MYL2) founder mutation carriers. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(23):1815-1822. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHV522

- Wang S, Cui H, Song C, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(5):694-701. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HRTHM.2018.12.017

- Miller CAS, Maron MS, Estes NAM, et al. Safety, Side Effects and Relative Efficacy of Medications for Rhythm Control of Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123(11):1859-1862. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2019.02.051

- Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Kardiologia Polska (Polish Heart Journal). 2014;72(11):1054-1126.