Thời gian điều trị kháng tiểu kép có thể ngắn hơn đối với stent DES thế hệ mới. Một phân tích trên 5054 bệnh nhân có đặt stent XIENCE V tại Hoa Kỳ đã cho thấy, trong thế giới thực, ngưng kháng tiểu cầu kép an toàn sau 1 tháng nếu bệnh nhân thuộc nhóm nguy cơ chuẩn (chỉ định đặt stent on label) và sau 6 tháng nếu không chọn lọc bệnh nhân (all-comers).

TS.BS. Hoàng Văn Sỹ

BV Chợ Rẫy

{article 1087}• {link}{title}{/link}{/article}

Phân tích kết luận rằng stent DES thế hệ mới thực sự tăng sự an toàn về biến cố này[35]. Phân tích của Stone và cs trên 11219 bệnh nhân có đặt stent thuộc nhóm stent XIENCE V đã cho thấy, huyết tắc trong stent trong 2 năm không thường xảy ra, với tỉ lệ 0,75%. Khoảng 50% biến cố xảy ra trong 30 ngày đầu tiên. Hầu hết, chiếm 80% cơn huyết tắc trong stent trong 2 năm xảy ra khi bệnh nhân vẫn đang uống kháng tiểu cầu kép. Tỉ lệ huyết tắc trong stent ở bệnh nhân ngưng kháng tiểu cầu kép tại bất cứ thời điểm nào cũng tương tự với bệnh nhân không ngưng kháng tiểu cầu kép bao giờ[35]. Naidu và cs[36]đề xuất kháng tiểu cầu kép ngưng sau 30 ngày không làm tăng tỉ lệ huyết tắc trong stent trong năm đầu sau thủ thuật khi sử dụng stent XIENCE V EES. Hơn nữa, phân tích gộp gần đây của Mehran và cs[37]cũng cho thấy huyết tắc trong stent có tỉ lệ rất thấp, 0,19% khi ngưng kháng tiểu cầu kép sau 1 tháng và không có sự khác biệt so với nhóm bệnh nhân không ngưng kháng tiểu cầu kép bao giờ, 0,26% trên bệnh nhân đặt stent XIENCE V EES. Tỉ lệ huyết tắc trong stent XIENCE V EES rất thấp và do vậy tại Châu Âu, stent XIENCE V và XIENCE PRIME nhận CE mark 3 tháng với kháng tiểu cầu kép. Tuy nhiên không nên lẫn lộn về thời gian tối ưu của kháng tiểu cầu kép sau stent DES. Thử nghiệm RESET đã cho thấy, kháng tiểu cầu kép 3 tháng so với 12 tháng ở bệnh nhân đặt stent zotarolimus (Endeavor) không khác biệt về biến cố tim mạch. Tuy nhiên cần lưu ý, Endeavor có thời gian phóng thích thuốc rất nhanh, trong 2 tuần, trong khi stent thế hệ mới Resolute phóng thích thuốc chậm hơn[38].

Sự phối hợp aspirin với một thuốc nhóm thienopyridine như clopidogrel hay ticlopidine trong các thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên đã cho thấy giảm tỉ lệ huyết tắc trong stent so với chỉ điều trị aspirin đơn độc hay aspirin phối hợp với warfarin[39-41]. Ticlodipine được thay thế bởi clopidogrel do tác dụng phụ của ticlopidine. Tuy nhiên, clopidogel cũng có những hạn chế nhất định.

Clopidogrel là một tiền chất, cần phải chuyển hóa thành dạng hoạt động qua men CYP2C19 để có hiệu quả ức chế tiểu cầu. Trong thể đa dạng, gen mã hóa CYP2C19 cũng mã hóa phản ứng tiểu cầu cao đối với clopidogrel, kết hợp với biến cố tim mạch ở bệnh nhân có can thiệp mạch vành. Hiện tại, giá trị lâm sàng của xét nghiệm đa hình dạng CYP2C19 hay hoạt tính tiểu cầu chưa chắc chắn. Sự kháng clopidogrel có thể do sự thay đổi của một gen mã hóa cytochrome P450 tại gan, đặc biệt là gen CYP2C19[42]. Kháng clopidogrel và ngưng clopidogrel trong vòng 6 tháng đầu sau đặt stent là một trong các yếu tố nguy cơ bị huyết tắc trong stent[30]. Một phần tư bệnh nhân có thể kháng với clopidogrel[43, 44]. Một phân tích gộp trên 3000 bệnh nhân đã cho thấy hoạt tính tiểu cầu cao với P2YC12 Reaction Unit (PRU) ≥ 230 được kết hợp với huyết tắc trong stent (HR=3,11; 95% CI:1,50–6,46; P=0,002)[45]. Thử nghiệm Gravitas đã cho thấy không có lợi ích khi gấp đôi liều clopidogrel từ 75 mg lên 150 mg mỗi ngày sau can thiệp mạch vành ở bệnh nhân có hoạt tính tiểu cầu cao khi đang điều trị clopidogrel[46]. Sự tương tác thuốc có thể làm giảm hiệu quả của clopidogrel. Các thuốc chuyển hóa qua hệ thống men CYP2C19 tại gan như thuốc ức chế bơm proton được lưu ý có thể tương tác với clopidogrel. Tuy nhiên nghiên cứu COGENT đã cho thấy không có sự tương tác về tim mạch rõ ràng giữa hai thuốc[47, 48]. Hạn chế khác của clopidogrellà khởi phát tác dụng chậm, cần vài giờ sau uống và đáp ứng thay đổi tùy theo bệnh nhân.

Liệu pháp kháng tiểu cầu kép aspirin và clopidogrel được xem là chế độ kháng tiểu cầu chuẩn sau can thiệp mạch vành. Tuy nhiên trên bệnh nhân nguy cơ cao hơn như hội chứng mạch vành cấp, bị huyết tắc trong stent dù đang đều trị kháng tiểu cầu kép liên tục nên xem xét điều chỉnh chế độ thuốc. Các thuốc kháng tiểu cầu thế hệ mới như prasugrel và ticagrelor là những thuốc có hiệu lực mạnh trong việc giảm nguy cơ huyết tắc trong stent. Bệnh nhân không đáp ứng với clopidogrel cũng đáp ứng tốt với các thuốc thế hệ mới này. Trong bệnh nhân với hội chứng mạch vành cấp, tỉ lệ huyết tắc trong stent giảm khi thay thế clopidogrel bằng các thuốc này, tuy nhiên cần xem xét đến nguy cơ xuất huyết[49, 50].

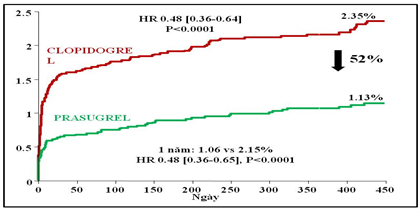

Prasugrel cũng là một tiền chất, cần chuyển hóa thành dạng hoạt tính bởi men P450. Khởi phát tác dụng nhanh hơn clopidogrel. Thử nghiệm TRITON-TIMI 38 thực hiện trên 12844 bệnh nhân với ít nhất một stent mạch vành được đặt trong 95% bệnh nhân cũng đã cho thấy, huyết tắc trong stent chắc chắn haycó khả năng tại thời điểm 1 năm trong nhóm prasugrel thấp hơn đáng kể so với nhóm clopidogrel,1,06% so với 2,15% (HR=0,48; 95% CI:0,36-0,65; P<0,0001); ngay cả huyết tắc trong stent sớm và muộn cũng thấp hơn, lần lượt, giảm nguy cơ 59% (0,64%so với 1,56%; p<0,0001) và 40% (0,49%so với 0,82%; p=0,03). Prasugrel làm giảm huyết tắc trong stent nhiều hơn so với clopidogrel ở cả bệnh nhân đặt stent BMS (n=6461;1,77%so với 2,84%; HR=0,63; 95%CI:0,45-0,89; p=0,007) và stent DES (n=5743; 1,13%so với 2,68%; HR=0,41; 95% CI:0,27-0,63; p<0,0001). Nghiên cứu TRITON-TMI 38 cũng cho thấy tỉ lệ xuất huyết cao hơn trong nhóm sử dụng prasugrel không phẫu thuật bắc cầu chủ vành. Xuất huyết chính trong nhóm prasugrel 2,4% so với 1,8%(HR=1,32; 95% CI:1,03-1,68;P=0,03); xuất huyết cần truyền máu cao hơn, 4,0% so với 3,0%(HR=1,34;95%CI:1,11-1,63; P<0,001). Cứ mỗi 1000 bệnh nhân điều trị với prasugrel sẽ làm giảm 12 bệnh nhân bị huyết tắc trong stent và 15 bệnh nhân bị biến cố tim mạch, nhưng tăng 5 bệnh nhân bị biến chứng xuất huyết chính[1].

Biểu đồ 2. Tỉ lệ huyết khối stent chắc chắn hay có khả năng trong nghiên cứu TRITON-TIMI 38

Ticagrelor là một thuốc ức chế không cạnh tranh có phục hồi thụ thể P2Y12 bằng một liên kết không phải liên kết cộng hóa trị tại vị trí khác với ADP trên thụ thể P2Y12,do vậykhông ảnh hưởng tớiviệc ADP gắn với thụ thể.Khác với thienopyridine như clopidogrelhay prasugrel ức chế cạnh tranh không hồi phục bằng liên kết cộng hóa trị trên thụ thể P2Y12, do vậy ngăn chặn vĩnh viễn ADP hoạt hóa tiểu cầu. Ticagrelor có hiệu lực ức chế tiểu cầu mạnh hơn và ổn định hơn clopidogrel. Nghiên cứu PLATO trên 18624 bệnh nhân hội chứng mạch vành cấp, trong đó có 11289 bệnh nhân có ít nhất một stent mạch vành đã cho thấy tỉ lệ huyết tắc trong stent trong nhóm ticagrelor thấp hơn so với nhóm clopidogrel.

Bảng 3. Tỉ lệ huyết tắc trong stent trong nghiên cứu PLATO

|

Huyết khối trong stent, n (%) |

Ticagrelor |

Clopidogrel (n=5,649) |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

|

− Chắc chắn − Có khả năng hoặc chắc chắn − Có thể, có khả năng hoặc chắc chắn |

71 (1,3) 118 (2,1) 155 (2,8) |

106 (1,9) 158 (2,8) 202 (3,6) |

0,67 (0,50–0,91) 0,75 (0,59–0,95) 0,77 (0,62–0,95) |

0,009 0,02 0.01 |

Ticagrelor, so với clopidogrel, làm giảm nguy cơ huyết khối stent trong hội chứng mạch vành cấp bất chấp đặc tính lâm sàng của bệnh nhân cũng như loại stent hay phương thức trị liệu. Không có sự khác biệt có ý nghĩa về tỷ lệ xuất huyết nặng chung, 11,6% so với 11,2% với p>0,05; không tăng tỷ lệ xuất huyết đe dọa tính mạng hay gây tử vong, 5,8% so với 5,8% với p>0,05 giữa hai thuốc. Tuy nhiên, ticagrelor tăng tần suất ngưng xoang trong tuần đầu, nhưng không có ý nghĩa về mặt lâm sàng; tăng tần suất khó thở, 13,8% so với 7,8%, p<0,001, nhưng thường khó thở mức độ nhẹ tới trung bình và thường một cơn duy nhất sau bắt đầu điều trị. Tuy vậy cũng cần thận trọng trên bệnh nhân có tiền căn hen hay COPD[51].

KẾT LUẬN

Huyết tắc trong stent là một biến chứng có tần suất thấp sau can thiệp đặt stent mạch vành, đặc biệt là stent DES. Tuy nhiên, đây là biến chứng nặng nề, tỉ lệ tử vong cao, gần 50% bệnh nhân bị huyết tắc trong stent tử vong.

Có nhiều yếu tố liên quan tới nguy cơ bị huyết tắc trong stent. Việc ngưng sớm kháng tiểu cầu kép là một trong những yếu tố nguy cơ mạnh nhất tiên lượng huyết tắc trong stent. Thời gian tối ưu của chế độ kháng tiểu cầu kép vẫn chưa được xác định. Nói chung các hướng dẫn khuyến cáo lý tưởng nên kéo dài tới 12 tháng.

Hầu hết huyết tắc trong stent xảy ra khi bệnh nhân vẫn còn đang điều trị kháng tiểu cầu kép. Những bệnh nhân nguy cơ cao như hội chứng mạch vành cấp hay tiền căn bị huyết tắc trong stent nên chuyển sang điều trị các thuốc kháng tiểu cầu thế hệ mới, là các thuốc có tác dụng ức chế tiểu cầu nhanh hơn, mạnh hơn như prasugrel hay ticagrelor. Prasugrel có nguy cơ xuất huyết tăng cao gấp 2 lần, trong khi ticagrelor không tăng nguy cơ xuất huyết so với thuốc clopidogrel.

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

1. Wiviott, S.D., et al., Intensive oral antiplatelet therapy for reduction of ischaemic events including stent thrombosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with percutaneous coronary intervention and stenting in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial: a subanalysis of a randomised trial. Lancet, 2008. 371(9621): p. 1353-63.

2. Cutlip, D.E., et al., Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation, 2007. 115(17): p. 2344-51.

3. Mauri, L., et al., Stent thrombosis in randomized clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med, 2007. 356(10): p. 1020-9.

4. Gupta, S. and M.M. Gupta, Stent thrombosis. J Assoc Physicians India, 2008. 56: p. 969-79.

5. Awata, M., et al., Serial angioscopic evidence of incomplete neointimal coverage after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: comparison with bare-metal stents. Circulation, 2007. 116(8): p. 910-6.

6. Cutlip, D.E., et al., Stent thrombosis in the modern era: a pooled analysis of multicenter coronary stent clinical trials. Circulation, 2001. 103(15): p. 1967-71.

7. Windecker, S. and B. Meier, Late coronary stent thrombosis. Circulation, 2007. 116(17): p. 1952-65.

8. van Werkum, J.W., et al., Long-term clinical outcome after a first angiographically confirmed coronary stent thrombosis: an analysis of 431 cases. Circulation, 2009. 119(6): p. 828-34.

9. Jensen, L.O., et al., Stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and death after drug-eluting and bare-metal stent coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007. 50(5): p. 463-70.

10. de la Torre-Hernandez, J.M., et al., Drug-eluting stent thrombosis: results from the multicenter Spanish registry ESTROFA (Estudio ESpanol sobre TROmbosis de stents FArmacoactivos). J Am Coll Cardiol, 2008. 51(10): p. 986-90.

11. Machecourt, J., et al., Risk factors for stent thrombosis after implantation of sirolimus-eluting stents in diabetic and nondiabetic patients: the EVASTENT Matched-Cohort Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007. 50(6): p. 501-8.

12. Spaulding, C., et al., Sirolimus-eluting versus uncoated stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med, 2006. 355(11): p. 1093-104.

13. Kastrati, A. and A. Schomig, Drug-eluting stents is their future as bright as their past? J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007. 50(2): p. 146-8.

14. Wenaweser, P., et al., Incidence and correlates of drug-eluting stent thrombosis in routine clinical practice. 4-year results from a large 2-institutional cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2008. 52(14): p. 1134-40.

15. Stone, G.W., et al., Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents: two-year clinical follow-up from the Clinical Evaluation of the Xience V Everolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System in the Treatment of Patients with de novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions (SPIRIT) III trial. Circulation, 2009. 119(5): p. 680-6.

16. Stone, G.W., et al., Randomized comparison of everolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. 2-year follow-up from the SPIRIT (Clinical Evaluation of the XIENCE V Everolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System) IV trial, in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011. p. 19-25.

17. Kedhi, E., et al., Second-generation everolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in real-life practice (COMPARE): a randomised trial, in Lancet. 2010. p. 201-9.

18. Silber, S., et al., Unrestricted randomised use of two new generation drug-eluting coronary stents: 2-year patient-related versus stent-related outcomes from the RESOLUTE All Comers trial, in Lancet. 2011. p. 1241-7.

19. de la Torre Hernandez, J.M. and S. Windecker, Very late stent thrombosis with newer drug-eluting stents: no longer an issue?, in Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2012. p. 595-8.

20. de la Torre Hernandez, J.M., et al., Thrombosis of second-generation drug-eluting stents in real practice results from the multicenter Spanish registry ESTROFA-2 (Estudio Espanol Sobre Trombosis de Stents Farmacoactivos de Segunda Generacion-2), in JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010. p. 911-9.

21. Daemen, J., et al., Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet, 2007. 369(9562): p. 667-78.

22. Iakovou, I., et al., Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA, 2005. 293(17): p. 2126-30.

23. Kuchulakanti, P.K., et al., Correlates and long-term outcomes of angiographically proven stent thrombosis with sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. Circulation, 2006. 113(8): p. 1108-13.

24. Kotani, J., et al., Incomplete neointimal coverage of sirolimus-eluting stents: angioscopic findings. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006. 47(10): p. 2108-11.

25. Obata, J.E., et al., Sirolimus-eluting stent implantation aggravates endothelial vasomotor dysfunction in the infarct-related coronary artery in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007. 50(14): p. 1305-9.

26. Joner, M., et al., Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006. 48(1): p. 193-202.

27. Sudhir, K., et al., Risk factors for coronary drug-eluting stent thrombosis: influence of procedural, patient, lesion, and stent related factors and dual antiplatelet therapy, in ISRN Cardiol. 2013. p. 748736.

28. Harold, J.G., et al., ACCF/AHA/SCAI 2013 Update of the Clinical Competence Statement on Coronary Artery Interventional Procedures: a Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians Task Force on Clinical Competence and Training (Writing Committee to Revise the 2007 Clinical Competence Statement on Cardiac Interventional Procedures), in Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013. p. E69-111.

29. Wijns, W., et al., Guidelines on myocardial revascularization, in Eur Heart J. 2010. p. 2501-55.

30. Airoldi, F., et al., Incidence and predictors of drug-eluting stent thrombosis during and after discontinuation of thienopyridine treatment. Circulation, 2007. 116(7): p. 745-54.

31. Tanzilli, G., et al., Effectiveness of two-year clopidogrel + aspirin in abolishing the risk of very late thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation (from the TYCOON [two-year ClOpidOgrel need] study). Am J Cardiol, 2009. 104(10): p. 1357-61.

32. Valgimigli, M., et al., Randomized comparison of 6- versus 24-month clopidogrel therapy after balancing anti-intimal hyperplasia stent potency in all-comer patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention Design and rationale for the PROlonging Dual-antiplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia study (PRODIGY), in Am Heart J. 2010. p. 804-11.

33. Valgimigli, M., et al., Short- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a randomized multicenter trial, in Circulation. 2012. p. 2015-26.

34. Mehran, R., et al., Cessation of dual antiplatelet treatment and cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PARIS): 2 year results from a prospective observational study. Lancet. 382(9906): p. 1714-22.

35. Krucoff, M.W., et al., A new era of prospective real-world safety evaluation primary report of XIENCE V USA (XIENCE V Everolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System condition-of-approval post-market study), in JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011. p. 1298-309.

36. Naidu, S.S., et al., Contemporary incidence and predictors of stent thrombosis and other major adverse cardiac events in the year after XIENCE V implantation: results from the 8,061-patient XIENCE V United States study, in JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012. p. 626-35.

37. R.Mehran, J.B.H., D. R. Rutledge,W. L. Lombardi, and M. W. Krucoff, Prevalence and predictors of dual antiplatelet therapy non-compliance after drug-eluting stent placement: one year-results from XIENCE V studies. 2013. p. Abstract presented at EuroPCR, Paris, France.

38. Meier, P. and A.J. Lansky, Optimal duration of clopidogrel therapy: the shorter the longer?, in Eur Heart J. 2013. p. 1705-7.

39. Schomig, A., et al., A randomized comparison of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy after the placement of coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med, 1996. 334(17): p. 1084-9.

40. Bertrand, M.E., et al., Double-blind study of the safety of clopidogrel with and without a loading dose in combination with aspirin compared with ticlopidine in combination with aspirin after coronary stenting : the clopidogrel aspirin stent international cooperative study (CLASSICS). Circulation, 2000. 102(6): p. 624-9.

41. Mehta, S.R., et al., Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet, 2001. 358(9281): p. 527-33.

42. Simon, T., et al., Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med, 2009. 360(4): p. 363-75.

43. Lau, W.C., et al., Contribution of hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 metabolic activity to the phenomenon of clopidogrel resistance. Circulation, 2004. 109(2): p. 166-71.

44. Gurbel, P.A., et al., Clopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pretreatment platelet reactivity. Circulation, 2003. 107(23): p. 2908-13.

45. Brar, S.S., et al., Impact of platelet reactivity on clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. A collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data, in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011. p. 1945-54.

46. Price, M.J., et al., Standard- vs high-dose clopidogrel based on platelet function testing after percutaneous coronary intervention: the GRAVITAS randomized trial, in JAMA. 2011. p. 1097-105.

47. O’Donoghue, M.L., et al., Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet, 2009. 374(9694): p. 989-97.

48. Bhatt, D.L., et al., Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease, in N Engl J Med. 2011. p. 1909-17.

49. Cannon, C.P., et al., Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes (PLATO): a randomised double-blind study, in Lancet. 2010. p. 283-93.

50. Montalescot, G., et al., Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2009. 373(9665): p. 723-31.

51. Steg, P.G., et al., Stent thrombosis with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: an analysis from the prospective, randomized PLATO trial, in Circulation. 2013. p. 1055-65.