TS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

- Vấn đề quan trọng thứ 6

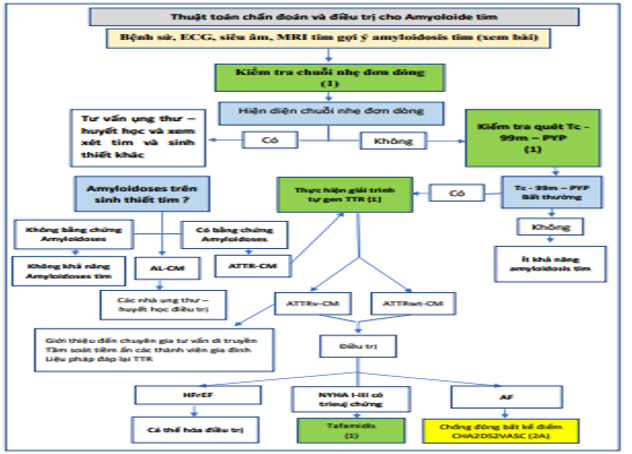

Bệnh tim amyloid có những khuyến cáo mới để điều trị. Các chiến lược cụ thể để chẩn đoán và điều trị bệnh amyloidosis tim được khuyến cáo (Hình 5). Ở những bệnh nhân có nghi ngờ lâm sàng về bệnh amyloidosis tim, nên kiểm tra chuỗi ánh sáng đơn dòng trong huyết thanh và nước tiểu bằng điện di cố định miễn dịch trong huyết thanh và nước tiểu và chuỗi ánh sáng tự do trong huyết thanh. Nếu không có bằng chứng về chuỗi ánh sáng đơn dòng trong huyết thanh hoặc nước tiểu, nên xạ hình xương để xác nhận sự hiện diện của amyloidosis tim transthyretin. Nếu bệnh amyloidosis tim do transthyretin được xác định, nên giải trình tự di truyền của gen TTR để phân biệt biến thể di truyền với amyloidosis tim do transthyretin loại hoang dã vì xác nhận một biến thể di truyền sẽ kích hoạt tư vấn di truyền và sàng lọc tiềm năng của các thành viên trong gia đình. Liệu pháp ổn định tetramer transthyretin (tafamidis) được khuyến cáo ở một số bệnh nhân mắc chứng amyloidosis tim transthyretin kiểu hoang dã hoặc biến thể. Chống đông máu là một chiến lược điều trị hợp lý để giảm nguy cơ đột quỵ ở bệnh nhân amyloidosis tim và AF.

Hình 5. Thuật toán chẩn đoán và Điều trị Amyloidosis Transthyretin Tim. Màu sắc tương ứng với COR trong Bảng 1. AF: rung nhĩ; AL-CM, bệnh cơ tim thể amyloid; ATTR-CM, bệnh cơ tim amyloid transthyretin; ATTRv, biến thể transthyretin amyloidosis; ATTRwt, bệnh amyloidosis transthyretin kiểu hoang dã; CHA2DS2-VASc, suy tim sung huyết, tăng huyết áp, ≥75 tuổi, đái tháo đường, đột quỵ hoặc cơn thiếu máu não thoáng qua (TIA), bệnh mạch máu, tuổi từ 65 đến 74, giới tính; ECG: điện tâm đồ; H / CL, tim đến lồng ngực hai bên; HFrEF, suy tim giảm phân suất tống máu; IFE, điện di cố định miễn dịch; MRI, chụp cộng hưởng từ; NYHA, Hiệp hội Tim mạch New York; PYP, pyrophosphat; Tc, tecneti; và TTR: transthyretin.

Các khuyến cáo cho chẩn đoán Amyloidosis tim

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ các khuyến nghị được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

|

I |

B-NR |

1. Những bệnh nhân có nghi ngờ lâm sàng về bệnh amyloidosis tim ∗ (94-98) nên được kiểm tra chuỗi nhẹ đơn dòng trong huyết thanh và nước tiểu bằng điện di cố định miễn dịch trong huyết thanh và nước tiểu và chuỗi nhẹ tự do trong huyết thanh (99). |

|

1 |

B-NR |

2. Ở những bệnh nhân có nghi ngờ lâm sàng cao về amyloidosis tim, không có bằng chứng về chuỗi nhẹ đơn dòng trong huyết thanh hoặc nước tiểu, nên thực hiện xạ hình xương để xác nhận sự hiện diện của amyloidosis tim do transthyretin (100). |

|

1 |

B-NR |

3. Ở những bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán amyloidosis tim do transthyretin, nên xét nghiệm di truyền với giải trình tự gen TTR để phân biệt biến thể di truyền với bệnh amyloidosis tim do transthyretin loại hoang dã (101). |

∗ Độ dày thành thất trái ≥14 mm kết hợp với mệt mỏi, khó thở hoặc phù, đặc biệt trong bối cảnh có sự chênh lệch giữa độ dày thành trên siêu âm tim và điện thế QRS trên ECG, và trong bệnh cảnh hẹp eo động mạch chủ, HFpEF, hội chứng ống cổ tay, hẹp cột sống, và bệnh đa dây thần kinh tự trị hoặc cảm giác.

Khuyến nghị điều trị bệnh Amyloidosis tim

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ các khuyến nghị được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

|

I |

B-R |

1. Ở một số bệnh nhân được lựa chọn bị amyloidosis do transthyretin dạng hoang dã hoặc biến thể và các triệu chứng HF NYHA từ I đến III, liệu pháp ổn định tetramer transthyretin (tafamidis) được chỉ định để giảm tử suất và bệnh suất do tim mạch (102). |

|

2a |

C-LD |

2. Ở những bệnh nhân bị amyloidosis tim và AF, kháng đông là hợp lý để giảm nguy cơ đột quỵ bất kể điểm CHA2DS2-VASc (suy tim sung huyết, tăng huyết áp, ≥75 tuổi, đái tháo đường, đột quỵ hoặc cơn thiếu máu cục bộ thoáng qua [TIA], bệnh mạch máu, tuổi từ 65 đến 74, loại giới tính) (103.104). |

2. Vấn đề quan trọng thứ 7

Bằng chứng hỗ trợ áp lực đổ đầy bị tăng lên là quan trọng để chẩn đoán HF nếu LVEF> 40% (Bảng 2). Các dấu hiệu và triệu chứng của HF không đặc hiệu và do đó chẩn đoán HF cần có bằng chứng hỗ trợ. Tăng áp lực đổ đầy tim là một đặc điểm của HF, và điều này được giả định ở những bệnh nhân có LVEF ≤40%. Tuy nhiên, nếu LVEF từ 41% đến 49% (giảm nhẹ) hoặc ≥50% (được bảo toàn), cần có bằng chứng về việc tăng áp lực đổ đầy LV tự phát hoặc có thể cho phép để xác định chẩn đoán HF. Bằng chứng cho việc tăng áp lực đổ đầy có thể thu được từ không xâm lấn (ví dụ, peptit natri lợi niệu, chức năng tâm trương trên hình ảnh) hoặc xét nghiệm xâm lấn (ví dụ, đo huyết động).

Bảng 2 Phân loại HF dựa vào LVEF

| Loại theo LVEF | Tiêu chuẩn |

| HFrEF (HF với EF giảm) | ▪ LVEF ≤ 40% |

| HFimEF (HF với EF được cải thiện | ▪ LVEF trước đó ≤40% và lần đo tiếp theo LVEF> 40% |

| HFmrEF (HF với EF giảm nhẹ) | ▪ LVEF 41% –49%

▪ Bằng chứng về việc tăng áp lực đổ đầy LV tự phát hoặc có thể cho thấy (ví dụ, peptide bài niệu natri tăng cao, đo huyết động không xâm lấn và xâm lấn) |

| HFpEF (HF với EF bảo tồn) | ▪ LVEF ≥50%

▪ Bằng chứng về việc tăng áp lực đổ đầy LV tự phát hoặc có thể bị thúc đẩy (ví dụ, peptide natri lợi niệu tăng cao, đo huyết động không xâm lấn và xâm lấn) |

| Vui lòng xem Phụ lục 1 để biết các ngưỡng đề xuất đối với bệnh tim cấu trúc và bằng chứng về việc tăng áp lực đổ đầy.

HF: suy tim; LV: thất trái; và LVEF: phân suất tống máu thất trái. |

|

3. Vấn đề quan trọng thứ 8

Những bệnh nhân bị HF giai đoạn nặng muốn kéo dài thời gian sống sót nên được chuyển đến một nhóm chuyên về HF. Một nhóm chuyên khoa HF, thường đặt tại một trung tâm HF nâng cao, xem xét việc quản lý HF, đánh giá sự phù hợp với các liệu pháp HF nâng cao (ví dụ: thiết bị trợ giúp thất trái, ghép tim) và sử dụng dịch vụ chăm sóc giảm nhẹ gồm thuốc inotrop giảm nhẹ phù hợp với mục tiêu chăm sóc của bệnh nhân.

Khuyến cáo cho giới thiệu chuyên khoa cho HF nâng cao

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

|

1 |

C-CD |

1 C-LD

1. Ở các bệnh nhân HF gia tăng, khi phù hợp với mục tiêu chăm sóc của bệnh nhân, nên chuyển tuyến kịp thời đến chăm sóc chuyên khoa HF để xem xét việc quản lý HF và đánh giá sự phù hợp với các liệu pháp HF nâng cao (ví dụ: thiết bị trợ giúp thất trái, ghép tim, chăm sóc giảm nhẹ, và inotrope giảm nhẹ) (105-110). |

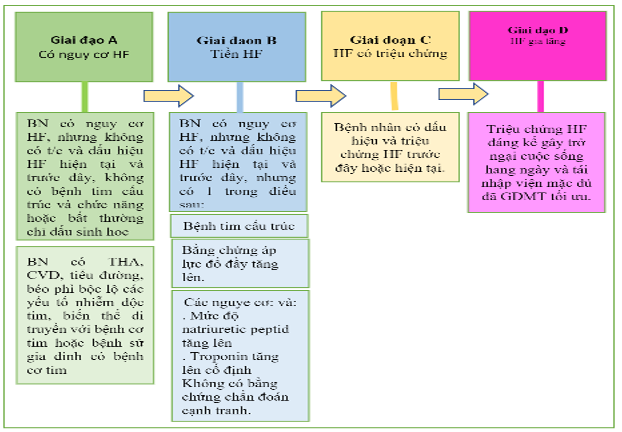

4. Vấn đề quan trọng thứ 9

Phòng ngừa tiên phát là quan trọng đối với những người có nguy cơ bị HF (giai đoạn A) hoặc tiền HF (giai đoạn B). Các giai đoạn của HF đã được sửa đổi để nhấn mạnh các thuật ngữ mới là “có nguy cơ mắc HF” (at-risk for HF) đối với giai đoạn A và “tiền HF” đối với giai đoạn B (Hình 6, Bảng 3). Trong hướng dẫn đầy đủ, phòng ngừa tiên phát gồm tất cả các chiến lược chăm sóc sức khỏe nhằm ngăn ngừa sự phát triển của HF có triệu chứng (giai đoạn C). Nên có thói quen sống lành mạnh, chẳng hạn như duy trì hoạt động thể chất thường xuyên, duy trì cân nặng bình thường và chế độ ăn uống lành mạnh. Huyết áp cần được kiểm soát theo các hướng dẫn thực hành lâm sàng đã được công bố. SGLT2i được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân tiểu đường loại 2 và bệnh tim mạch đã hình thành hoặc có nguy cơ tim mạch cao. Tầm soát trên cơ sở chỉ dấu sinh học natriuretic peptide tiếp theo bằng chăm sóc theo nhóm, gồm cả bác sĩ chuyên khoa tim mạch, có thể hữu ích để ngăn ngừa sự phát triển của rối loạn chức năng thất trái (tâm thu hoặc tâm trương) hoặc HF mới khởi phát (tiền HF, giai đoạn B). Điểm nguy cơ đa biến đã được xác thực cũng có thể hữu ích để ước tính nguy cơ biến cố HF. Ở những bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng với LVEF ≤40% (trước HF, giai đoạn B), ACEi, ARB, thuốc chẹn beta dựa trên bằng chứng, statin và cấy máy khử rung tim được khuyến cáo ở một số bệnh nhân nhất định.

Hình 6. Các giai đoạn của HF theo ACC / AHA

Hình 6. Các giai đoạn của HF theo ACC / AHA

Các giai đoạn HF theo ACC / AHA được hiển thị. ACC: Trường Môn Tim Mạch Học Hoa Kỳ; AHA: Hiệp hội Tim mạch Hoa Kỳ; CVD, bệnh tim mạch; GDMT, liệu pháp y tế theo hướng dẫn; và HF, suy tim. BN: bệnh nhân. T/C: triệu chứng.

Bảng 3. Các giai đoạn HF

| Các giai đoạn | Định nghĩa và tiêu chuẩn |

| Giai đoạn A. Nguy cơ cho HF | Có nguy cơ HF nhưng không có triệu chứng, bệnh tim cấu trúc hoặc chỉ dấu sinh học tim về căng giãn hoặc chấn thương (ví dụ: bệnh nhân cao huyết áp, CVD xơ vữa động mạch, tiểu đường, hội chứng chuyển hóa và béo phì, tiếp xúc với các tác nhân gây độc tim, biến thể di truyền của bệnh cơ tim hoặc tiền sử gia đình dương tính của bệnh cơ tim). |

| Tiền HF | Không có triệu chứng hoặc dấu hiệu của HF và bằng chứng của một trong những điều sau: |

| Bệnh tim cấu trúc ∗ | |

| ▪ Giảm chức năng tâm thu thất trái hoặc phải | |

| ▪ Giảm phân suất tống máu, giảm sức căng (strain) | |

| ▪ Phì đại thất | |

| ▪ Giãn lớn buồng tim | |

| ▪ Các bất thường về chuyển động thành | |

| ▪ Bệnh van tim | |

| Bằng chứng về việc tăng áp lực đổ đầy ∗ | |

| ▪ Bằng các phép đo huyết động xâm lấn | |

| ▪ Bằng hình ảnh không xâm lấn cho thấy áp lực đổ đầy tăng cao (ví dụ, siêu âm tim Doppler) | |

| Bệnh nhân có các yếu tố nguy cơ và | |

| ▪ Tăng mức độ peptit lợi tiểu natri loại B ∗ hoặc | |

| ▪ Tăng liên tục troponin tim | |

| trong trường hợp không có các chẩn đoán cạnh tranh dẫn đến tăng các dấu ấn sinh học như hội chứng mạch vành cấp, suy thận, thuyên tắc phổi hoặc viêm cơ tim | |

| Giai đoạn C: HF có triệu chứng | Bệnh tim cấu trúc với các triệu chứng hiện tại hoặc trước đây của HF. |

| Giai đoạn D: HF tiến triển (advanced) | Các triệu chứng HF đáng kể gây trở ngại cho cuộc sống hàng ngày và nhập viện tái phát mặc dù đã cố gắng tối ưu hóa GDMT. |

| CKD: bệnh thận mãn tính; CVD: bệnh tim mạch; GDMT: điều trị y học theo hướng dẫn và HF: suy tim.

∗ Để biết các ngưỡng thay đổi cấu trúc tim, chức năng, tăng áp lực làm đầy và và chỉ dấu sinh học, hãy tham khảo Phụ lục 1. |

|

Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân có nguy cơ mắc bệnh HF (Giai đoạn A: Phòng ngừa ban đầu)

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ các khuyến cáo được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

|

1

|

A |

1. Ở bệnh nhân THA, huyết áp nên được kiểm soát theo GDMT cho THA để ngăn ngừa HF có triệu chứng (46,111-118). |

|

1 |

A |

2. Ở các bệnh nhân tiểu đường loại 2 và bệnh tim mạch đã xác lập hoặc có nguy cơ tim mạch cao, nên sử dụng SGLT2i để ngăn ngừa nhập viện vì HF (119-121). |

|

1 |

B-NR |

3. Trong dân số nói chung, thói quen lối sống lành mạnh như hoạt động thể chất thường xuyên, duy trì cân nặng bình thường, chế độ ăn uống lành mạnh và tránh hút thuốc là hữu ích để giảm nguy cơ HF trong tương lai (122-130). |

|

2a |

B-A |

4. Đối với các bệnh nhân có nguy cơ phát triển HF, sàng lọc dựa trên dấu ấn sinh học natriuretic peptide, sau đó là chăm sóc theo nhóm, bao gồm cả chuyên gia tim mạch tối ưu hóa GDMT, có thể hữu ích để ngăn ngừa sự phát triển của rối loạn chức năng LV (tâm thu hoặc tâm trương) hoặc HF mới khởi phát (131,132). |

|

2a |

B–NR |

5. Trong dân số nói chung, điểm số nguy cơ đa biến đã được xác nhận có thể hữu ích để ước tính nguy cơ biến cố HF có thể xảy ra (133-135). |

Các khuyến cáo để quản lý giai đoạn B: Ngăn ngừa hội chứng suy tim lâm sàng ở bệnh nhân tiền HF

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ các khuyến nghị được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

|

1

|

A |

1. Ở các bệnh nhân có LVEF ≤40%, ACEi nên được sử dụng để ngăn ngừa HF có triệu chứng và giảm tỷ lệ tử vong (15,17,136,137). |

|

1 |

A |

2. Ở các bệnh nhân có tiền sử nhồi máu cơ tim hoặc hội chứng vành cấp mới đây hoặc từ lâu, nên sử dụng statin để ngăn ngừa HF có triệu chứng và các biến cố tim mạch có hại (138-142). |

|

1 |

B-NR |

3. Ở các bệnh nhân bị nhồi máu cơ tim mới đây và LVEF ≤40% không dung nạp ACEi, ARB nên được sử dụng để ngăn ngừa HF có triệu chứng và giảm tỷ lệ tử vong (143). |

|

1 |

B-R |

4. Ở các bệnh nhân có tiền sử nhồi máu cơ tim mới đây hoặc từ lâu hoặc hội chứng mạch vành cấp và LVEF ≤ 40%, nên sử dụng thuốc chẹn beta dựa trên bằng chứng để giảm tỷ lệ tử vong (144-146). |

|

1 |

B-R |

5. Ở các bệnh nhân ít nhất 40 ngày sau nhồi máu cơ tim với LVEF ≤30% và NYHA class I có triệu chứng trong khi điều trị GDMT và có kỳ vọng sống sót có ý nghĩa trong > 1 năm, cấy máy khử rung tim được khuyến cáo để phòng ngừa đột tử do tim tiên phát để giảm tử suất toàn bộ (147). |

|

1 |

C-LD |

6. Ở các bệnh nhân có LVEF ≤ 40%, beta blockers nên được sử dụng để ngăn chặn HF có triệu chứng (145,146). |

|

3: Có hại |

B-R |

7. Ở các bệnh nhân có LVEF <50%, không nên sử dụng thiazolidinediones vì chúng làm tăng nguy cơ HF, kể cả nhập viện (148). |

|

3: Có hại |

C-LD |

8. Ở các bệnh nhân có LVEF <50%, thuốc chẹn kênh canxi nondihydropyridine với tác dụng inotrop âm tính có thể có hại (149,150) |

5. Vấn đề quan trọng thứ 10

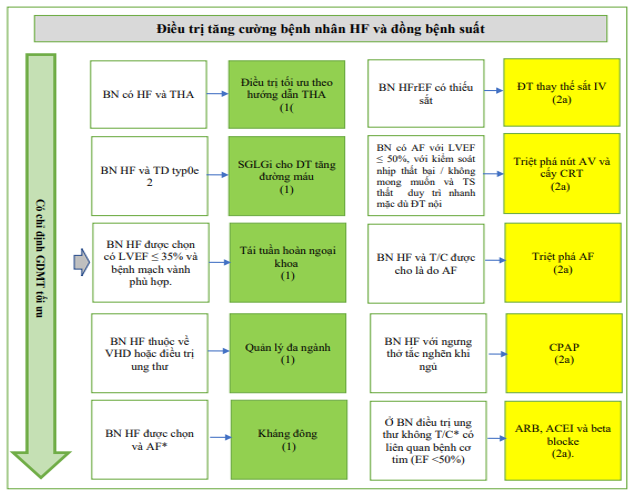

Các khuyến cáo điều trị cụ thể được cung cấp cho bệnh nhân HF và một số bệnh đi kèm (Hình 7). Các khuyến cáo được cung cấp cho một số bệnh nhân HF và thiếu sắt, thiếu máu, tăng huyết áp, rối loạn giấc ngủ, tiểu đường type 2, AF, bệnh động mạch vành và bệnh ác tính.

Hỉnh 7. Khuyến cáo điều trị bệnh nhân HF và các bệnh đi kèm được chọn

Màu sắc tương ứng với COR trong Bảng 1. Các khuyến cáo về điều trị cho bệnh nhân HF và một số bệnh đi kèm được hiển thị. ∗ Bệnh nhân HF mãn tính với AF kịch phát – vĩnh viễn – dai dẳng và điểm CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 (đối với nam) và ≥3 (đối với nữ). ACEi: chất ức chế men chuyển; AF: rung nhĩ; ARB: thuốc chẹn thụ thể angiotensin; AV, nhĩ thất; CHA2DS2-VASc, suy tim sung huyết, tăng huyết áp, tuổi ≥75, đái tháo đường, đột quỵ hoặc cơn thoáng thiếu máu cục bộ [TIA], bệnh mạch máu, tuổi từ 65 đến 74, giới tính; CPAP, thở áp lực dương liên tục; CRT, liệu pháp tái đồng bộ tim; EF, phân suất tống máu; GDMT, liệu pháp y tế theo hướng dẫn; HF, suy tim; HFrEF, suy tim với giảm phân suất tống máu; IV, tiêm tĩnh mạch; LVEF, phân suất tống máu thất trái; NYHA, Hiệp hội Tim mạch New York; SGLT2i, chất ức chế natri-glucose cotransporter 2; và VHD, bệnh van tim.

Các khuyến nghị về quản lý các bệnh đi kèm ở bệnh nhân bị HF

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ các khuyến nghị được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

| Quản lý thiếu máu hoặc thiếu sắt | ||

| 2a | B-R | 1. Ở các bệnh nhân HFrEF và thiếu sắt có hoặc không kèm theo thiếu máu, thay thế sắt qua đường tĩnh mạch là hợp lý để cải thiện tình trạng chức năng và chất lượng cuộc sống (151-154). |

| 3: Có hại | B-R | 2. Ở bệnh nhân HF và thiếu máu, không nên sử dụng các chất kích thích erythropoietin để cải thiện bệnh suất và tử suất (155,156). |

| Quản lý tăng huyết áp | ||

| 1 | C-LD | 3. Ở bệnh nhân HFrEF và tăng huyết áp, chuẩn liều GDMT đến liều mục tiêu dung nạp tối đa được khuyến cáo (157-159). |

| Quản lý rồi loạn giấc ngủ | ||

| 2a | B-R | 4. Ở bệnh nhân HF và ngưng thở khi ngủ do tắc nghẽn, áp lực đường thở dương liên tục có thể hợp lý để cải thiện chất lượng giấc ngủ và giảm buồn ngủ ban ngày (160-163). |

| 2a | C-LD | 5. Ở những bệnh nhân bị HF và nghi ngờ có rối loạn nhịp thở khi ngủ, đánh giá giấc ngủ chính thức là hợp lý để xác định chẩn đoán và phân biệt giữa chứng ngưng thở khi ngủ do tắc nghẽn và trung ương (160,164). |

| 3: Có hại | B-R | 6. Ở bệnh nhân NYHA độ II đến IV HFrEF và ngưng thở khi ngủ trung ương, thông khí cơ chế cơ học thích ứng gây hại (162,163). |

| Quản lý tiểu đường | ||

| 1 | A | 7. Ở bệnh nhân HF và đái tháo đường týp 2, việc sử dụng SGLT2i được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát tăng đường huyết và giảm tử suất và bệnh suất liên quan đến HF (31,32,165,166). |

Khuyến cáo về Quản lý AF trong HF

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ các khuyến cáo được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

| 1 | A | 1. Bệnh nhân HF mãn tính với AF kịch phát – vĩnh viễn – dai dẳng và điểm CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 (đối với nam) và ≥3 (đối với nữ) nên được điều trị chống đông máu kéo dài (167-171). |

| 1 | A | 2. Đối với bệnh nhân HF mãn tính với AF kịch phát – vĩnh viễn – dai dẳng, thuốc chống đông máu đường uống tác dụng trực tiếp được khuyến cáo thay vì warfarin ở những bệnh nhân đủ điều kiện (168-176). |

| 2a | B-R | 3. Đối với bệnh nhân HF và các triệu chứng do AF, triệt phá AF là hợp lý để cải thiện các triệu chứng và chất lượng cuộc sống (177-180). |

| 2a | B-R | 4. Đối với những bệnh nhân có AF và LVEF ≤50%, nếu chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp không thành công hoặc không được mong muốn, và tần số thất vẫn nhanh mặc dù điều trị thuốc, triệt phá nút nhĩ thất với cấy thiết bị điều trị tái đồng bộ tim là hợp lý (181-188) . |

| 2a | B-NR | 5. Đối với bệnh nhân HF mãn tính và AF kịch phát – vĩnh viễn – dai dẳng, liệu pháp chống đông máu kéo dài là hợp lý cho nam và nữ mà không có thêm các yếu tố nguy cơ (189-192). |

Khuyến cáo về tái tuần hoàn cho bệnh động mạch vành

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ khuyến nghị được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

| 1 | B-R | 1. Ở một số bệnh nhân HF được chọn, EF giảm (EF ≤35%) và giải phẫu mạch vành phù hợp, phẫu thuật tái thông mạch cộng với GDMT có lợi để cải thiện các triệu chứng, nhập viện vì tim mạch và tử vong lâu dài do mọi nguyên nhân (193-200). |

Khuyến cao cho Tim mạch-Ung thư

Các nghiên cứu tham khảo hỗ trợ các khuyến nghị được tóm tắt trong Phần bổ sung dữ liệu trực tuyến.

| COR | LOE | Các khuyến cáo |

| 1 | B-NR | 1. Ở các bệnh nhân phát triển bệnh cơ tim liên quan đến điều trị ung thư hoặc HF, một cuộc thảo luận đa ngành liên quan đến bệnh nhân về tỷ lệ nguy cơ-lợi ích của việc gián đoạn, ngừng hoặc tiếp tục điều trị ung thư được khuyến cáo để cải thiện việc quản lý (201,202). |

| 2a | B-NR

|

2. Ở các bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng với bệnh cơ tim liên quan đến điều trị ung thư (EF <50%), ARB, ACEi và thuốc chẹn beta là hợp lý để ngăn chặn sự tiến triển thành HF và cải thiện chức năng tim (202-204). |

| 2a | B-NR | 3. Ở các bệnh nhân có các yếu tố nguy cơ tim mạch hoặc bệnh tim đã biết đang được xem xét điều trị ung thư có khả năng gây độc cho tim, việc đánh giá chức năng tim trước trị liệu là hợp lý để thiết lập chức năng tim cơ bản và hướng dẫn lựa chọn liệu pháp điều trị ung thư (202,205-216). |

| 2a | B-NR | 4. Ở các bệnh nhân có các yếu tố nguy cơ tim mạch hoặc bệnh tim đã biết đang được điều trị bằng thuốc chống ung thư có thể gây độc cho tim, việc theo dõi chức năng tim là hợp lý để xác định sớm bệnh cơ tim do thuốc (202.204.206.208). |

| 2b | B-R | 5. Ở các bệnh nhân có nguy cơ mắc bệnh cơ tim liên quan đến điều trị ung thư, việc bắt đầu dùng thuốc chẹn beta và ACEi / ARB để phòng ngừa tiên phát bệnh cơ tim do thuốc không có lợi ích chắc chắn (217-228). |

| 2b | C-LD | 6. Ở các bệnh nhân đang được xem xét điều trị có khả năng gây độc cho tim, đo troponin tim hàng loạt có thể hợp lý để phân tầng nguy cơ hơn nữa (229-232). |

PHỤ LỤC – DỮ LIỆU BỔ SUNG

Phụ lục 1

Phụ lục cho Bảng 2 và 3: Ngưỡng đề xuất cho bệnh tim cấu trúc và bằng chứng về việc gia tăng áp lực đổ đầy.

| Hình thái học | ▪ LAVI ≥29 mL/m2 |

| ▪ LVMI >116/95 g/m2 | |

| ▪ RWT >0.42 | |

| ▪ LV wall thickness ≥12 mm | |

| Chức năng tâm thu thất | ▪ LVEF <50% |

| ▪ GLS <16% | |

| Chức năng tâm trương thất | ▪ E / eʹ trung bình ≥15 khi tăng áp lực đổ đầy |

| ▪ eʹ vách <7 cm / s | |

| ▪ eʹ bên <10 cm / s | |

| ▪ Vận tốc TR > 2,8 m / s | |

| ▪ Áp lực tâm thu PA được ước tính > 35 mm Hg | |

| Chỉ dấu sinh học | ▪ BNP ≥35 pg / mL ∗ |

| ▪ NT-proBNP ≥125 pg / mL ∗ |

AF: rung nhĩ; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; CKD: bệnh thận mãn tính; GLS, Sức căng theo chiều dọc toàn bộ; HF: suy tim; LAVI, chỉ số thể tích nhĩ trái; LVMI, chỉ số khối cơ thất trái; NT-proBNP: natriuretic peptide tests; PA, động mạch phổi; RWT, độ dày thành tương đối; và TR: hở van ba lá.

∗ Các đường cắt cung cấp mức natriuretic peptide có thể có độ đặc hiệu thấp hơn, đặc biệt ở bệnh nhân lớn tuổi hoặc bệnh nhân AF hoặc suy thận. Thông thường, các giá trị ngưỡng cao hơn được khuyến cáo để chẩn đoán HF ở những bệnh nhân này. Các ngưỡng natriuretic peptide được chọn để sàng lọc dân số cho tiền HF (giai đoạn B HF) có thể <99% giới hạn tham chiếu và cần được xác định theo dân số có nguy cơ.

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO (Xem đầy đủ trên http://www.timmachhoc.vn)

1.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al.. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.Circulation. 2013; 128:e240–e327.LinkGoogle Scholar

2.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al.. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America.Circulation. 2017; 136:e137–e161.LinkGoogle Scholar

3.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al.. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.Circulation. 2019; 140:e596–e646.LinkGoogle Scholar

4.Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al.. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.Circulation. 2021; 143:e72-e227.LinkGoogle Scholar

5.Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al.. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.Circulation. Published online April 1, 2022. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063Google Scholar

6.ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Methodology manual and policies from the ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2010, American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association; 2010.Accessed June 3, 2020. https://www.acc.org/guidelines/about-guidelines-and-clinical-documents/methodology and https://professional.heart.org/-/media/phd-files/guidelines-and-statements/methodology_manual_and_policies_ucm_319826.pdfGoogle Scholar

7.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al.. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure.N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:993–1004.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

8.Wachter R, Senni M, Belohlavek J, et al.. Initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in haemodynamically stabilised heart failure patients in hospital or early after discharge: primary results of the randomised TRANSITION study.Eur J Heart Fail. 2019; 21:998–1007.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

9.Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, et al.. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in acute decompensated heart failure.N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:539–548.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

10.Desai AS, Solomon SD, Shah AM, et al.. Effect of sacubitril-valsartan vs enalapril on aortic stiffness in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial.JAMA. 2019; 322:1077–1084.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

11.Wang Y, Zhou R, Lu C, et al.. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitor on cardiac reverse remodeling: meta-analysis.J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e012272.Google Scholar

12.Consensus Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS).N Engl J Med. 1987; 316:1429–1435.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

13.SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure.N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:293–302.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

14.Packer M, Poole-Wilson PA, Armstrong PW, et al.. Comparative effects of low and high doses of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril, on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure. ATLAS Study Group. Circulation. 1999; 100:2312–2318.LinkGoogle Scholar

15.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moyé LA, et al.. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction: results of the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Trial. The SAVE Investigators.N Engl J Med. 1992; 327:669–677.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

16.Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators.Lancet. 1993; 342:821–828.MedlineGoogle Scholar

17.Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlsen JE, et al.. A clinical trial of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group.N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:1670–1676.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

18.Garg R, Yusuf S. Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on ACE Inhibitor Trials.JAMA. 1995; 273:1450–1456.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

19.Woodard-Grice AV, Lucisano AC, Byrd JB, et al.. Sex-dependent and race-dependent association of XPNPEP2 C-2399A polymorphism with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema.Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010; 20:532–536.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

20.Cohn JN, Tognoni G, Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure.N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1667–1675.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

21.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al.. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both.N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:1893–1906.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

22.Konstam MA, Neaton JD, Dickstein K, et al.. Effects of high-dose versus low-dose losartan on clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure (HEAAL study): a randomised, double-blind trial.Lancet. 2009; 374:1840–1848.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

23.ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, et al.. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events.N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:1547–1559.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

24.Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo K, et al.. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial.Lancet. 2008; 372:1174–1183.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

25.Cardiac Insufficiency Authors.The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial.Lancet. 1999; 353:9–13.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

26.Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF).Lancet. 1999; 353:2001–2007.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

27.Packer M, Fowler MB, Roecker EB, et al.. Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study.Circulation. 2002; 106:2194–2199.LinkGoogle Scholar

28.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al.. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure.N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:709–717.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

29.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al.. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction.N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:1309–1321.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

30.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al.. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms.N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:11–21.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

31.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al.. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1995–2008.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

32.Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al.. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure.N Engl J Med. 2020; 383:1413–1424.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

33.Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al.. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction.N Engl J Med. 2021; 385:1451–1461.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

34.Cleland JGF, Bunting KV, Flather MD, et al.. Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: an individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials.Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:26–35.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

35.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al.. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1609–1620.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

36.Halliday BP, Wassall R, Lota AS, et al.. Withdrawal of pharmacological treatment for heart failure in patients with recovered dilated cardiomyopathy (TRED-HF): an open-label, pilot, randomised trial.Lancet. 2019; 393:61–73.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

37.Nilsson BB, Lunde P, Grogaard HK, et al.. Long-term results of high-intensity exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in revascularized patients for symptomatic coronary artery disease.Am J Cardiol. 2018; 121:21–26.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

38.Solomon SD, Claggett B, Desai AS, et al.. Influence of ejection fraction on outcomes and efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan (lcz696) in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial.Circ Heart Fail. 2016; 9:e002744.LinkGoogle Scholar

39.Tsuji K, Sakata Y, Nochioka K, et al.. Characterization of heart failure patients with mid-range left ventricular ejection fraction-a report from the CHART-2 Study.Eur J Heart Fail. 2017; 19:1258–1269.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

40.Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M al CBLe. Sacubitril/valsartan across the spectrum of ejection fraction in heart failure.Circulation. 2020; 141:352–361.LinkGoogle Scholar

41.Zheng SL, Chan FT, Nabeebaccus AA, et al.. Drug treatment effects on outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Heart. 2018; 104:407–415.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

42.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, et al.. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:1383–1392.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

43.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, et al.. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial.Circulation. 2015; 131:34–42.LinkGoogle Scholar

44.Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood-pressure-lowering treatment in hypertension: 9. Discontinuations for adverse events attributed to different classes of antihypertensive drugs: meta-analyses of randomized trials.J Hypertens. 2016; 34:1921–1932.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

45.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al.. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial.JAMA. 2016; 315:2673–2682.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

46.Group SR, Wright JT, Williamson JD, et al.. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control.N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2103–2116.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

47.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, et al.. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial.Lancet. 2003; 362:777–781.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

48.Lund LH, Claggett B, Liu J, et al.. Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction in CHARM: characteristics, outcomes and effect of candesartan across the entire ejection fraction spectrum.Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; 20:1230–1239.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

49.Redfield MM, Anstrom KJ, Levine JA, et al.. Isosorbide mononitrate in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2314–2324.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

50.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, et al.. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial.JAMA. 2013; 309:1268–1277.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

51.Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, et al.. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and Task Force on Practice Guidelines.Circulation. 2014; 129:2329–2345.LinkGoogle Scholar

52.Banka G, Heidenreich PA, Fonarow GC. Incremental cost-effectiveness of guideline-directed medical therapies for heart failure.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:1440–1446.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

53.Dasbach EJ, Rich MW, Segal R, et al.. The cost-effectiveness of losartan versus captopril in patients with symptomatic heart failure.Cardiology. 1999; 91:189–194.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

54.Glick H, Cook J, Kinosian B, et al.. Costs and effects of enalapril therapy in patients with symptomatic heart failure: an economic analysis of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Treatment Trial.J Card Fail. 1995; 1:371–380.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

55.Paul SD, Kuntz KM, Eagle KA, et al.. Costs and effectiveness of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in patients with congestive heart failure.Arch Intern Med. 1994; 154:1143–1149.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

56.Reed SD, Friedman JY, Velazquez EJ, et al.. Multinational economic evaluation of valsartan in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT).Am Heart J. 2004; 148:122–128.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

57.Shekelle P, Morton S, Atkinson S, et al.. Pharmacologic management of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction: effect in female, black, and diabetic patients, and cost-effectiveness.Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2003:1–6.Google Scholar

58.Tsevat J, Duke D, Goldman L, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of captopril therapy after myocardial infarction.J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995; 26:914–919.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

59.Gaziano TA, Fonarow GC, Claggett B, et al.. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.JAMA Cardiol. 2016; 1:666–672.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

60.Gaziano TA, Fonarow GC, Velazquez EJ, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of sacubitril-valsartan in hospitalized patients who have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.JAMA Cardiol. 2020; 5:1236–1244.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

61.King JB, Shah RU, Bress AP, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of sacubitril-valsartan combination therapy compared with enalapril for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2016; 4:392–402.Google Scholar

62.Sandhu AT, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Owens DK, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of implantable pulmonary artery pressure monitoring in chronic heart failure.J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2016; 4:368–375.Google Scholar

63.Caro JJ, Migliaccio-Walle K, O’Brien JA, et al.. Economic implications of extended-release metoprolol succinate for heart failure in the MERIT-HF trial: a US perspective of the MERIT-HF trial.J Card Fail. 2005; 11:647–656.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

64.Delea TE, Vera-Llonch M, Richner RE, et al.. Cost effectiveness of carvedilol for heart failure.Am J Cardiol. 1999; 83:890–896.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

65.Gregory D, Udelson JE, Konstam MA. Economic impact of beta blockade in heart failure.Am J Med 2001;110(suppl 7A):74S–80S.MedlineGoogle Scholar

66.Vera-Llonch M, Menzin J, Richner RE, et al.. Cost-effectiveness results from the US Carvedilol Heart Failure Trials Program.Ann Pharmacother. 2001; 35:846–851.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

67.Glick HA, Orzol SM, Tooley JF, et al.. Economic evaluation of the randomized aldactone evaluation study (RALES): treatment of patients with severe heart failure.Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2002; 16:53–59.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

68.Weintraub WS, Zhang Z, Mahoney EM, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of eplerenone compared with placebo in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure.Circulation. 2005; 111:1106–1113.LinkGoogle Scholar

69.Zhang Z, Mahoney EM, Kolm P, et al.. Cost effectiveness of eplerenone in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction who were taking both ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers: subanalysis of the EPHESUS.Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010; 10:55–63.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

70.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Tam SW, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of fixed-dose combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine therapy for blacks with heart failure.Circulation. 2005; 112:3745–3753.LinkGoogle Scholar

71.Al-Khatib SM, Anstrom KJ, Eisenstein EL, et al.. Clinical and economic implications of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-II.Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142:593–600.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

72.Cowie MR, Marshall D, Drummond M, et al.. Lifetime cost-effectiveness of prophylactic implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator in patients with reduced left ventricular systolic function: results of Markov modelling in a European population.Europace. 2009; 11:716–726.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

73.Mark DB, Nelson CL, Anstrom KJ, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of defibrillator therapy or amiodarone in chronic stable heart failure: results from the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT).Circulation. 2006; 114:135–142.LinkGoogle Scholar

74.Mushlin AI, Hall WJ, Zwanziger J, et al.. The cost-effectiveness of automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators: results from MADIT. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial.Circulation. 1998; 97:2129–2135.LinkGoogle Scholar

75.Sanders GD, Hlatky MA, Owens DK. Cost-effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators.N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1471–1480.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

76.Zwanziger J, Hall WJ, Dick AW, et al.. The cost effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT)-II.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:2310–2318.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

77.Feldman AM, de Lissovoy G, Bristow MR, et al.. Cost effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy in the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) trial.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:2311–2321.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

78.Gold MR, Padhiar A, Mealing S, et al.. Economic value and cost-effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy among patients with mild heart failure: projections from the REVERSE long-term follow-up.J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2017; 5:204–212.Google Scholar

79.Heerey A, Lauer M, Alsolaiman F, et al.. Cost effectiveness of biventricular pacemakers in heart failure patients.Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2006; 6:129–137.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

80.Nichol G, Kaul P, Huszti E, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with symptomatic heart failure.Ann Intern Med. 2004; 141:343–351.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

81.Noyes K, Veazie P, Hall WJ, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy in the MADIT-CRT trial.J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013; 24:66–74.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

82.Woo CY, Strandberg EJ, Schmiegelow MD, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of adding cardiac resynchronization therapy to an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator among patients with mild heart failure.Ann Intern Med. 2015; 163:417–426.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

83.Parizo JT, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Salomon JA, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for treatment of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.JAMA Cardiol. 2021; 6:926–935.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

84.Isaza N, Calvachi P, Raber I, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4:e2114501.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

85.Long EF, Swain GW, Mangi AA. Comparative survival and cost-effectiveness of advanced therapies for end-stage heart failure.Circ Heart Fail. 2014; 7:470–478.LinkGoogle Scholar

86.Kazi DS, Bellows BK, Baron SJ, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of tafamidis therapy for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy.Circulation. 2020; 141:1214–1224.LinkGoogle Scholar

87.Baras Shreibati J, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Banerjee D, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of left ventricular assist devices in ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure.J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2017; 5:110–119.Google Scholar

88.Mahr C, McGee E, Cheung A, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of thoracotomy approach for the implantation of a centrifugal left ventricular assist device.ASAIO J. 2020; 66:855–861.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

89.Rogers JG, Bostic RR, Tong KB, et al.. Cost-effectiveness analysis of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy.Circ Heart Fail. 2012; 5:10–16.LinkGoogle Scholar

90.Silvestry SC, Mahr C, Slaughter MS, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of a small intrapericardial centrifugal left ventricular assist device.ASAIO J. 2020; 66:862–870.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

91.Martinson M, Bharmi R, Dalal N, et al.. Pulmonary artery pressure-guided heart failure management: US cost-effectiveness analyses using the results of the CHAMPION clinical trial.Eur J Heart Fail. 2017; 19:652–660.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

92.Schmier JK, Ong KL, Fonarow GC. Cost-effectiveness of remote cardiac monitoring with the cardiomems heart failure system.Clin Cardiol. 2017; 40:430–436.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

93.Lindenfeld J, Zile MR, Desai AS, et al.. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF): a randomised controlled trial.Lancet. 2021; 398:991–1001.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

94.Castano A, Narotsky DL, Hamid N, et al.. Unveiling transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and its predictors among elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement.Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:2879–2887.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

95.Gonzalez-Lopez E, Gallego-Delgado M, Guzzo-Merello G, et al.. Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.Eur Heart J. 2015; 36:2585–2594.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

96.Sperry BW, Reyes BA, Ikram A, et al.. Tenosynovial and cardiac amyloidosis in patients undergoing carpal tunnel release.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:2040–2050.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

97.Westermark P, Westermark GT, Suhr OB, et al.. Transthyretin-derived amyloidosis: probably a common cause of lumbar spinal stenosis.Ups J Med Sci. 2014; 119:223–228.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

98.Maurer MS, Hanna M, Grogan M, et al.. Genotype and phenotype of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: THAOS (Transthyretin Amyloid Outcome Survey).J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68:161–172.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

99.Muchtar E, Gertz MA, Kyle RA, et al.. A modern primer on light chain amyloidosis in 592 patients with mass spectrometry-verified typing.Mayo Clin Proc. 2019; 94:472–483.MedlineGoogle Scholar

100.Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, et al.. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis.Circulation. 2016; 133:2404–2412.LinkGoogle Scholar

101.Brown EE, Lee YZJ, Halushka MK, et al.. Genetic testing improves identification of transthyretin amyloid (ATTR) subtype in cardiac amyloidosis.Amyloid. 2017; 24:92–95.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

102.Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, et al.. Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy.N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:1007–1016.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

103.El-Am EA, Dispenzieri A, Melduni RM, et al.. Direct current cardioversion of atrial arrhythmias in adults with cardiac amyloidosis.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73:589–597.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

104.Feng D, Syed IS, Martinez M, et al.. Intracardiac thrombosis and anticoagulation therapy in cardiac amyloidosis.Circulation. 2009; 119:2490–2497.LinkGoogle Scholar

105.Crespo-Leiro MG, Metra M, Lund LH, et al.. Advanced heart failure: a position statement of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology.Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; 20:1505–1535.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

106.Fang JC, Ewald GA, Allen LA, et al.. Advanced (stage D) heart failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee.J Card Fail. 2015; 21:519–534.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

107.Greenberg B, Fang J, Mehra M, et al.. Advanced heart failure: trans-atlantic perspectives on the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology position statement.Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; 20:1536–1539.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

108.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al.. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.Circulation. 2009; 119:e391–e479.LinkGoogle Scholar

109.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al.. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America.Circulation. 2016; 134:e282–e293.MedlineGoogle Scholar

110.Thomas R, Huntley A, Mann M, et al.. Specialist clinics for reducing emergency admissions in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.Heart. 2013; 99:233–239.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

111.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al.. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older.N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:1887–1898.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

112.Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al.. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Lancet. 2016; 387:957–967.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

113.Kostis JB, Davis BR, Cutler J, et al.. Prevention of heart failure by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1997; 278:212–216.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

114.Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al.. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators.Lancet. 1997; 350:757–764.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

115.Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure-lowering treatment. 6. Prevention of heart failure and new-onset heart failure–meta-analyses of randomized trials.J Hypertens. 2016; 34:373–384.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

116.Upadhya B, Rocco M, Lewis CE, et al.. Effect of intensive blood pressure treatment on heart failure events in the Systolic Blood Pressure Reduction Intervention Trial.Circ Heart Fail. 2017; 10:e003613.LinkGoogle Scholar

117.Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al.. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure.JAMA. 1996; 275:1557–1562.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

118.Butler J, Kalogeropoulos AP, Georgiopoulou VV, et al.. Systolic blood pressure and incident heart failure in the elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study and the Health, Ageing and Body Composition Study.Heart. 2011; 97:1304–1311.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

119.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al.. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes.N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:644–657.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

120.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al.. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes.N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:347–357.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

121.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al.. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes.N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2117–2128.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

122.Del Gobbo LC, Kalantarian S, Imamura F, et al.. Contribution of major lifestyle risk factors for incident heart failure in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study.J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2015; 3:520–528.Google Scholar

123.Wang Y, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, et al.. Lifestyle factors in relation to heart failure among Finnish men and women.Circ Heart Fail. 2011; 4:607–612.LinkGoogle Scholar

124.Young DR, Reynolds K, Sidell M, et al.. Effects of physical activity and sedentary time on the risk of heart failure.Circ Heart Fail. 2014; 7:21–27.LinkGoogle Scholar

125.Hu G, Jousilahti P, Antikainen R, et al.. Joint effects of physical activity, body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio on the risk of heart failure.Circulation. 2010; 121:237–244.LinkGoogle Scholar

126.Folsom AR, Shah AM, Lutsey PL, et al.. American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7: avoiding heart failure and preserving cardiac structure and function.Am J Med. 2015; 128:970–976.e972.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

127.Tektonidis TG, Åkesson A, Gigante B, et al.. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced risk of heart failure in men.Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18:253–259.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

128.Levitan EB, Wolk A, Mittleman MA. Consistency with the DASH diet and incidence of heart failure.Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:851–857.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

129.Levitan EB, Wolk A, Mittleman MA. Relation of consistency with the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet and incidence of heart failure in men aged 45 to 79 years.Am J Cardiol. 2009; 104:1416–1420.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

130.Lara KM, Levitan EB, Gutierrez OM, et al.. Dietary patterns and incident heart failure in US adults without known coronary disease.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73:2036–2045.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

131.Ledwidge M, Gallagher J, Conlon C, et al.. Natriuretic peptide-based screening and collaborative care for heart failure: the STOP-HF randomized trial.JAMA. 2013; 310:66–74.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

132.Huelsmann M, Neuhold S, Resl M, et al.. PONTIAC (NT-proBNP selected prevention of cardiac events in a population of diabetic patients without a history of cardiac disease): a prospective randomized controlled trial.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:1365–1372.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

133.Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, et al.. Profile for estimating risk of heart failure.Arch Intern Med. 1999; 159:1197–1204.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

134.Butler J, Kalogeropoulos A, Georgiopoulou V, et al.. Incident heart failure prediction in the elderly: the health ABC heart failure score.Circ Heart Fail. 2008; 1:125–133.LinkGoogle Scholar

135.Agarwal SK, Chambless LE, Ballantyne CM, et al.. Prediction of incident heart failure in general practice: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study.Circ Heart Fail. 2012; 5:422–429.LinkGoogle Scholar

136.SOLVD InvestigatorsYusuf S, Pitt B, et al.. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions.N Engl J Med. 1992; 327:685–691.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

137.Jong P, Yusuf S, Rousseau MF, et al.. Effect of enalapril on 12-year survival and life expectancy in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a follow-up study.Lancet. 2003; 361:1843–1848.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

138.Afilalo J, Majdan AA, Eisenberg MJ. Intensive statin therapy in acute coronary syndromes and stable coronary heart disease: a comparative meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.Heart. 2007; 93:914–921.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

139.Heart Protection Study Collaborative GroupEmberson JR, Ng LL, et al.. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, vascular disease risk, and cholesterol reduction among 20 536 patients in the MRC/BHF heart protection study.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49:311–319.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

140.Preiss D, Campbell RT, Murray HM, et al.. The effect of statin therapy on heart failure events: a collaborative meta-analysis of unpublished data from major randomized trials.Eur Heart J. 2015; 36:1536–1546.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

141.Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Cannon CP, et al.. Intensive statin therapy and the risk of hospitalization for heart failure after an acute coronary syndrome in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 study.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:2326–2331.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

142.Strandberg TE, Holme I, Faergeman O, et al.. Comparative effect of atorvastatin (80 mg) versus simvastatin (20 to 40 mg) in preventing hospitalizations for heart failure in patients with previous myocardial infarction.Am J Cardiol. 2009; 103:1381–1385.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

143.Velazquez EJ, Pfeffer MA, McMurray JV, et al.. VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial: baseline characteristics in context.Eur J Heart Fail. 2003; 5:537–544.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

144.Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial.Lancet. 2001; 357:1385–1390.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

145.Exner DV, Dries DL, Waclawiw MA, et al.. Beta-adrenergic blocking agent use and mortality in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a post hoc analysis of the studies of left ventricular dysfunction.J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33:916–923.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

146.Vantrimpont P, Rouleau JL, Wun CC, et al.. Additive beneficial effects of beta-blockers to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) Study. SAVE Investigators.J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997; 29:229–236.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

147.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al.. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction.N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:877–883.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

148.Dargie HJ, Hildebrandt PR, Riegger GA, et al.. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the effects of rosiglitazone on echocardiographic function and cardiac status in type 2 diabetic patients with New York Heart Association functional class I or II heart failure.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49:1696–1704.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

149.Multicenter Diltiazem Postinfarction Trial Research Group. The effect of diltiazem on mortality and reinfarction after myocardial infarction.N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:385–392.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

150.Goldstein RE, Boccuzzi SJ, Cruess D, et al.. Diltiazem increases late-onset congestive heart failure in postinfarction patients with early reduction in ejection fraction.Circulation. 1991; 83:52–60.LinkGoogle Scholar

151.Anker SD, Comin Colet J, Filippatos G, et al.. Ferric carboxymaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency.N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:2436–2448.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

152.Ponikowski P, van Veldhuisen DJ, Comin-Colet J, et al.. Beneficial effects of long-term intravenous iron therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in patients with symptomatic heart failure and iron deficiencydagger.Eur Heart J. 2015; 36:657–668.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

153.Beck-da-Silva L, Piardi D, Soder S, et al.. IRON-HF study: a randomized trial to assess the effects of iron in heart failure patients with anemia.Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168:3439–3442.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

154.Ponikowski P, Kirwan BA, Anker SD, et al.. Ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency at discharge after acute heart failure: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial.Lancet. 2020; 396:1895–1904.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

155.Swedberg K, Young JB, Anand IS, et al.. Treatment of anemia with darbepoetin alfa in systolic heart failure.N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:1210–1219.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

156.Kang J, Park J, Lee JM, et al.. The effects of erythropoiesis stimulating therapy for anemia in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials.Int J Cardiol. 2016; 218:12–22.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

157.Banach M, Bhatia V, Feller MA, et al.. Relation of baseline systolic blood pressure and long-term outcomes in ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate heart failure.Am J Cardiol. 2011; 107:1208–1214.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

158.Lee TT, Chen J, Cohen DJ, et al.. The association between blood pressure and mortality in patients with heart failure.Am Heart J. 2006; 151:76–83.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

159.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al.. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.Hypertension. 2018; 71:e13–e115.LinkGoogle Scholar

160.Arzt M, Schroll S, Series F, et al.. Auto-servoventilation in heart failure with sleep apnoea: a randomised controlled trial.Eur Respir J. 2013; 42:1244–1254.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

161.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Fiuzat M, et al.. Cardiovascular outcomes with minute ventilation-targeted adaptive servo-ventilation therapy in heart failure: the CAT-HF trial.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:1577–1587.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

162.Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al.. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure.N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:1095–1105.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

163.Yamamoto S, Yamaga T, Nishie K, et al.. Positive airway pressure therapy for the treatment of central sleep apnoea associated with heart failure.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019; 12:CD012803.MedlineGoogle Scholar

164.Arzt M, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al.. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP).Circulation. 2007; 115:3173–3180.LinkGoogle Scholar

165.Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al.. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials.Lancet. 2020; 396:819–829.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

166.Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O, et al.. Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus.Circulation. 2019; 139:2528–2536.LinkGoogle Scholar

167.Mason PK, Lake DE, DiMarco JP, et al.. Impact of the CHA2DS2-VASc score on anticoagulation recommendations for atrial fibrillation.Am J Med. 2012; 125:603e601–603e606.CrossrefGoogle Scholar

168.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al.. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1139–1151.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

169.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al.. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:883–891.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

170.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al.. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:981–982.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

171.Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al.. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:2093–2104.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

172.Ferreira J, Ezekowitz MD, Connolly SJ, et al.. Dabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and symptomatic heart failure: a subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trial.Eur J Heart Fail. 2013; 15:1053–1061.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

173.McMurray JJ, Ezekowitz JA, Lewis BS, et al.. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, heart failure, and the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial.Circ Heart Fail. 2013; 6:451–460.LinkGoogle Scholar

174.Siller-Matula JM, Pecen L, Patti G, et al.. Heart failure subtypes and thromboembolic risk in patients with atrial fibrillation: the PREFER in AF-HF substudy.Int J Cardiol. 2018; 265:141–147.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

175.Magnani G, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, et al.. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: insights from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48.Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18:1153–1161.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

176.Savarese G, Giugliano RP, Rosano GM, et al.. Efficacy and safety of novel oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a meta-analysis.J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2016; 4:870–880.Google Scholar

177.Di Biase L, Mohanty P, Mohanty S, et al.. Ablation versus amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with congestive heart failure and an implanted device: results from the AATAC multicenter randomized trial.Circulation. 2016; 133:1637–1644.LinkGoogle Scholar

178.Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, et al.. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure.N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:417–427.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

179.Chen S, Purerfellner H, Meyer C, et al.. Rhythm control for patients with atrial fibrillation complicated with heart failure in the contemporary era of catheter ablation: a stratified pooled analysis of randomized data.Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:2863–2873.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

180.Packer DL, Piccini JP, Monahan KH, et al.. Ablation versus drug therapy for atrial fibrillation in heart failure: results from the CABANA trial.Circulation. 2021; 143:1377–1390.LinkGoogle Scholar

181.Wood MA, Brown-Mahoney C, Kay GN, et al.. Clinical outcomes after ablation and pacing therapy for atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis.Circulation. 2000; 101:1138–1144.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

182.Brignole M, Menozzi C, Gianfranchi L, et al.. Assessment of atrioventricular junction ablation and VVIR pacemaker versus pharmacological treatment in patients with heart failure and chronic atrial fibrillation: a randomized, controlled study.Circulation. 1998; 98:953–960.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

183.Doshi RN, Daoud EG, Fellows C, et al.. Left ventricular-based cardiac stimulation post AV nodal ablation evaluation (the PAVE study).J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005; 16:1160–1165.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

184.Brignole M, Gammage M, Puggioni E, et al.. Comparative assessment of right, left, and biventricular pacing in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation.Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:712–722.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

185.Brignole M, Botto G, Mont L, et al.. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients undergoing atrioventricular junction ablation for permanent atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial.Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:2420–2429.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

186.Brignole M, Pokushalov E, Pentimalli F, et al.. A randomized controlled trial of atrioventricular junction ablation and cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and narrow QRS. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:3999–4008.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

187.Chatterjee NA, Upadhyay GA, Ellenbogen KA, et al.. Atrioventricular nodal ablation in atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of biventricular vs. right ventricular pacing mode.Eur J Heart Fail. 2012; 14:661–667.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

188.Prabhu S, Taylor AJ, Costello BT, et al.. Catheter ablation versus medical rate control in atrial fibrillation and systolic dysfunction: the CAMERA-MRI study.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70:1949–1961.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

189.Freudenberger RS, Hellkamp AS, Halperin JL, et al.. Risk of thromboembolism in heart failure: an analysis from the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HEFT).Circulation. 2007; 115:2637–2641.LinkGoogle Scholar

190.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al.. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).Eur Heart J. 2010; 31:2369–2429.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

191.Melgaard L, Gorst-Rasmussen A, Lane DA, et al.. Assessment of the CHA2DS2-VASc score in predicting ischemic stroke, thromboembolism, and death in patients with heart failure with and without atrial fibrillation.JAMA. 2015; 314:1030–1038.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

192.Mogensen UM, Jhund PS, Abraham WT, et al.. Type of atrial fibrillation and outcomes in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70:2490–2500.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

193.Caracciolo EA, Davis KB, Sopko G, et al.. Comparison of surgical and medical group survival in patients with left main equivalent coronary artery disease. Long-term CASS experience. Circulation. 1995; 91:2335–2344.LinkGoogle Scholar

194.Howlett JG, Stebbins A, Petrie MC, et al.. CABG improves outcomes in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: 10-year follow-up of the STICH Trial.J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2019; 7:878–887.Google Scholar

195.Mark DB, Knight JD, Velazquez EJ, et al.. Quality-of-life outcomes with coronary artery bypass graft surgery in ischemic left ventricular dysfunction: a randomized trial.Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161:392–399.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

196.Park S, Ahn JM, Kim TO, et al.. Revascularization in patients with left main coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76:1395–1406.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

197.Petrie MC, Jhund PS, She L, et al.. Ten-year outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting according to age in patients with heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction: an analysis of the extended follow-up of the STICH Trial (Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure).Circulation. 2016; 134:1314–1324.LinkGoogle Scholar

198.Tam DY, Dharma C, Rocha R, et al.. Long-term survival after surgical or percutaneous revascularization in patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary disease.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76:1153–1164.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

199.Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al.. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction.N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:1607–1616.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

200.Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, et al.. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:1511–1520.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

201.Wang SY, Long JB, Hurria A, et al.. Cardiovascular events, early discontinuation of trastuzumab, and their impact on survival.Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014; 146:411–419.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

202.Guarneri V, Lenihan DJ, Valero V, et al.. Long-term cardiac tolerability of trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience.J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:4107–4115.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

203.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Lamantia G, et al.. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: clinical relevance and response to pharmacologic therapy.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:213–220.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

204.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Bacchiani G, et al.. Early detection of anthracycline cardiotoxicity and improvement with heart failure therapy.Circulation. 2015; 131:1981–1988.LinkGoogle Scholar

205.Chavez-MacGregor M, Zhang N, Buchholz TA, et al.. Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity among older patients with breast cancer.J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:4222–4228.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

206.Goldhar HA, Yan AT, Ko DT, et al.. The temporal risk of heart failure associated with adjuvant trastuzumab in breast cancer patients: a population study.J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016; 108:djv301.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

207.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Shannon T, et al.. Incidence and predictors of congestive heart failure after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation.Blood. 2011; 118:6023–6029.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

208.Henry ML, Niu J, Zhang N, et al.. Cardiotoxicity and cardiac monitoring among chemotherapy-treated breast cancer patients.J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2018; 11:1084–1093.CrossrefGoogle Scholar

209.Wang L, Tan TC, Halpern EF, et al.. Major cardiac events and the value of echocardiographic evaluation in patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy.Am J Cardiol. 2015; 116:442–446.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

210.Seferina SC, de Boer M, Derksen MW, et al.. Cardiotoxicity and cardiac monitoring during adjuvant trastuzumab in daily Dutch practice: a study of the Southeast Netherlands Breast Cancer Consortium.Oncologist. 2016; 21:555–562.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

211.Abu-Khalaf MM, Safonov A, Stratton J, et al.. Examining the cost-effectiveness of baseline left ventricular function assessment among breast cancer patients undergoing anthracycline-based therapy.Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019; 176:261–270.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

212.Truong SR, Barry WT, Moslehi JJ, et al.. Evaluating the utility of baseline cardiac function screening in early-stage breast cancer treatment.Oncologist. 2016; 21:666–670.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

213.Jeyakumar A, DiPenta J, Snow S, et al.. Routine cardiac evaluation in patients with early-stage breast cancer before adjuvant chemotherapy.Clin Breast Cancer. 2012; 12:4–9.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

214.Steuter J, Bociek R, Loberiza F, et al.. Utility of prechemotherapy evaluation of left ventricular function for patients with lymphoma.Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015; 15:29–34.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

215.Conrad AL, Gundrum JD, McHugh VL, et al.. Utility of routine left ventricular ejection fraction measurement before anthracycline-based chemotherapy in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.J Oncol Pract. 2012; 8:336–340.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

216.O’Brien P, Matheson K, Jeyakumar A, et al.. The clinical utility of baseline cardiac assessments prior to adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019; 174:357–363.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

217.Akpek M, Ozdogru I, Sahin O, et al.. Protective effects of spironolactone against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy.Eur J Heart Fail. 2015; 17:81–89.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

218.Avila MS, Ayub-Ferreira SM, de Barros Wanderley MR, et al.. Carvedilol for prevention of chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity: the CECCY trial.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71:2281–2290.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

219.Bosch X, Rovira M, Sitges M, et al.. Enalapril and carvedilol for preventing chemotherapy-induced left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with malignant hemopathies: the OVERCOME trial (preventiOn of left Ventricular dysfunction with Enalapril and caRvedilol in patients submitted to intensive ChemOtherapy for the treatment of Malignant hEmopathies).J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:2355–2362.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

220.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Sandri MT, et al.. Prevention of high-dose chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity in high-risk patients by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition.Circulation. 2006; 114:2474–2481.LinkGoogle Scholar

221.Guglin M, Krischer J, Tamura R, et al.. Randomized trial of lisinopril versus carvedilol to prevent trastuzumab cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73:2859–2868.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

222.Gulati G, Heck SL, Ree AH, et al.. Prevention of cardiac dysfunction during adjuvant breast cancer therapy (PRADA): a 2 x 2 factorial, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of candesartan and metoprolol.Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:1671–1680.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

223.Kalay N, Basar E, Ozdogru I, et al.. Protective effects of carvedilol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:2258–2262.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

224.Pituskin E, Mackey JR, Koshman S, et al.. Multidisciplinary approach to novel therapies in cardio-oncology research (MANTICORE 101-Breast): a randomized trial for the prevention of trastuzumab-associated cardiotoxicity.J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35:870–877.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

225.Shah P, Garris R, Abboud R, et al.. Meta-analysis comparing usefulness of beta blockers to preserve left ventricular function during anthracycline therapy.Am J Cardiol. 2019; 124:789–794.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

226.Cardinale D, Ciceri F, Latini R, et al.. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: a multicenter randomised trial comparing two strategies for guiding prevention with enalapril: the International CardioOncology Society-one trial.Eur J Cancer. 2018; 94:126–137.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

227.Vaduganathan M, Hirji SA, Qamar A, et al.. Efficacy of neurohormonal therapies in preventing cardiotoxicity in patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy.J Am Coll Cardiol CardioOnc. 2019; 1:54–65.Google Scholar

228.Wittayanukorn S, Qian J, Westrick SC, et al.. Prevention of trastuzumab and anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or beta-blockers in older adults with breast cancer.Am J Clin Oncol. 2018; 41:909–918.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

229.Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Colombo A, et al.. Prognostic value of troponin I in cardiac risk stratification of cancer patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy.Circulation. 2004; 109:2749–2754.LinkGoogle Scholar

230.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Torrisi R, et al.. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: clinical and prognostic implications of troponin I evaluation.J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:3910–3916.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

231.Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Martinoni A, et al.. Left ventricular dysfunction predicted by early troponin I release after high-dose chemotherapy.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 36:517–522.CrossrefMedlineGoogle Scholar

232.Zardavas D, Suter TM, Van Veldhuisen DJ, et al.. Role of troponins I and T and N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide in monitoring cardiac safety of patients with early-stage human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer receiving trastuzumab: a herceptin adjuvant study cardiac marker substudy.J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35:878–884.MedlineGoogle Scholar