TS. BS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

7.1.3.1.3. Ngăn ngừa đột tử tim thứ phát và quản lý rồi loạn nhịp thất.

Ba thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên (AVID, CASH, và CIDS) đã so sánh liệu pháp ICD và điều trị nội khoa để phòng ngừa thứ phát ở bệnh nhân sau khi CA được cứu thoát hoặc VT không dung nạp. [349.351.352] Ba thử nghiệm thu nhận tổng cộng 1963 bệnh nhân trong đó chỉ có 292 (14,8%) có nguyên nhân không phải do thiếu máu cục bộ. Việc giảm đáng kể tỷ lệ tử vong do bất kỳ nguyên nhân nào ở bệnh nhân mắc ICD đã được chứng minh, điều này gần như hoàn toàn do giảm 50% tỷ lệ tử vong do rối loạn nhịp tim. [352] Trong phân nhóm bệnh nhân mắc bệnh cơ tim, có xu hướng tương tự nhưng không đáng kể trong việc giảm tử vong. [352] RCT đã loại trừ những bệnh nhân có VT dung nạp được về mặt huyết động. Ở bệnh nhân DCM, chất nền VT ít được xác định rõ ràng hơn và cần phải xem xét tiến triển của bệnh. Do đó, mặc dù thiếu dữ liệu, nhóm chuyên gia này chia sẻ quan điểm rằng ICD cũng nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân DCM có VT dung nạp huyết động.

Tối ưu hóa lập trình ICD (xem Phần 6.2.3.1) có thể làm giảm các cú sốc ICD được cung cấp để đáp ứng với VT, nhưng thường cần phải điều trị bổ sung để giảm các đợt VA có triệu chứng. Trong thử nghiệm OPTIC, [412] bệnh nhân được cấy ICD trong vòng 21 ngày kể từ VT/VF được chọn ngẫu nhiên dùng amiodarone cộng với thuốc chẹn beta, sotalol đơn thuần hoặc thuốc chẹn beta đơn thuần. Tỷ lệ sốc ICD sau 1 năm lần lượt là 10,3%, 24,3% và 38,5%. Hiệu quả cao hơn của amiodarone cộng với thuốc chẹn beta so với sotalol cần phải được cân nhắc với tỷ lệ tác dụng phụ liên quan đến thuốc cao hơn trên cơ sở từng cá nhân. [318] Mặc dù chỉ có dữ liệu hạn chế, thuốc chẹn kênh natri có thể kiểm soát VT trong SHD và có thể có lợi ở những người nhận ICD mà không bị suy tim tiến triển. Phần lớn SMVT là do vào lại liên quan đến sẹo, có thể được điều trị bằng cách cắt bỏ qua catheter. Kết quả triệt phá cấp thời đã được báo cáo là tương tự đối với CAD và DCM. [497,663] Tuy nhiên, tỷ lệ tái phát VT thường cao hơn ở bệnh nhân DCM (tỷ lệ sống sót không có VT là 40,5% ở DCM so với 57% ở CAD sau 1 năm). [497] Sau nhiều thủ thuật ở 36% bệnh nhân, không bị VT lâu dài có thể đạt được ở 69% trường hợp trong một đoàn hệ hồi cứu, một trung tâm gồm 282 bệnh nhân được điều trị từ năm 1999 đến năm 2014. [664]

Triệt phá thượng tâm mạc là cần thiết trong 27–30% các thủ thuật. [497,664] Kết quả đặc biệt kém và các chiến lược cứu trợ (triệt phá bằng ethanol qua vành, triệt phá lưỡng cực, triệt phá bằng phẫu thuật) có thể được yêu cầu ở những bệnh nhân có đột biến gây bệnh (gen LMNA) và ở những người có vị trí chất nền sâu xuyên thành, trước vách ngăn. [499,665,666] Do tính phức tạp của quy trình triệt phá, bệnh nhân DCM chỉ nên được điều trị tại các trung tâm chuyên khoa.

Bảng khuyến cáo 28 — Các khuyến cáo phân tầng nguy cơ, ngăn ngừa đột tử tim và điều trị rồi loạn nhịp thất trong bệnh cơ tim giãn / bệnh cơ tim giảm động không giãn

| Recommendation | Classa | Levelb |

| Đánh giá chẩn đoán và khuyến cáo chung | ||

| Xét nghiệm di truyền (bao gồm ít nhất các gen LMNA, PLN, RBM20 và FLNC) được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân DCM/HNDCM và chậm dẫn truyền AV ở độ tuổi 50 hoặc những người có tiền sử gia đình DCM/HNDCM hoặc SCD ở người thân thế hệ thứ nhất (ở độ tuổi < 50) .[641–645] |

I |

B |

| CMR với LGE nên được xem xét ở bệnh nhân DCM/HNDCM để đánh giá nguyên nhân và nguy cơ VA/SCD. [129,651,667] |

IIa |

B |

| Xét nghiệm di truyền (gồm ít nhất các gen LMNA, PLN, RBM 20 và FLNC) nên được xem xét để phân tầng nguy cơ ở những bệnh nhân DCM/HNDCM dường như lẻ tẻ, xuất hiện ở độ tuổi trẻ hoặc có dấu hiệu nghi ngờ về nguyên nhân di truyền. [641–645] |

IIa |

C |

| Việc tham gia tập luyện cường độ cao gồm các môn thể thao cạnh tranh không được khuyến khích đối với những người DCM/HNDCM và đột biến LMNA. [655] |

III |

C |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ và phòng ngừa SCD tiên phát | ||

| Việc cấy ICD nên được cân nhắc ở những bệnh nhân mắc DCM/HNDCM, suy tim có triệu chứng (NYHA độ II–III) và LVEF<35% sau ≥ 3 tháng điều trị OMT. [357,359,635,650] |

IIa |

A

|

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở các bệnh nhân DCM/HNDCM có đột biến gây bệnh ở gen LMNA, nếu nguy cơ 5 năm đe dọa tính mạng được ước tính ≥10%c và có sự hiện diện của NSVT hoặc LVEF < 50% hoặc chậm dẫn truyền AV. [80,652,653] |

IIa |

B |

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở các bệnh nhân DCM/HNDCM có LVEF < 50% và ≥2 yếu tố nguy cơ (ngất, LGE trên CMR, SMVT cảm ứng ở PES, các đột biến gây bệnh ở các gen LMNA, d PLN, FLNC và RBM20). |

IIa |

C |

| Ở bệnh nhân DCM/HNDM, nên xem xét đánh giá điện sinh lý khi ngất vẫn không giải thích được sau khi đánh giá không xâm lấn. [661,668] |

IIa |

C |

| Ngăn ngừa SCD thứ phát và điều trị VAs | ||

| Cấy ICD được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân có DCM/HNDCM, những người sống sót sau SCA do VT/ VF hoặc trải qua SMVT không dung nạp huyết động. [349,351,352] |

I |

B |

| Triệt phá ở các trung tâm chuyên khoa nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân DCM/HNDCM và SMVT tái phát có triệu chứng hoặc ICD sốc cho SMVT, ở những người AADs không hiệu quả, chống chỉ định, hoặc không dung nạp. [481,497,664,669] |

IIa |

C |

| Việc bổ sung uống amiodarone hoặc thay thế thuốc chẹn beta bằng sotalol nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có DCM/HNDCM và ICD có trải nghiệm VA tái phát, có triệu chứng mặc dù đã lập trình thiết bị và điều trị thuốc chẹn beta tối ưu. [318] |

IIa |

B |

| Việc cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân mắc DCM/HNDCM và SMVT dung nạp được về mặt huyết động. |

IIa |

C |

| Quản lý người thân của bệnh nhân hoặc nạn nhân SCD với DCM/HNDCM | ||

| Ở người thân thế hệ thứ nhất của bệnh nhân DCM/HNDCM, ECG và siêu âm tim được khuyến nghị nếu:

• bệnh nhân đầu tiên được chẩn đoán < 50 tuổi hoặc có các đặc điểm lâm sàng gợi ý nguyên nhân di truyền, hoặc • có tiền sử gia đình mắc bệnh này. DCM / HNDCM hoặc SD sớm không mong muốn. [646] |

I |

C |

| Ở người thân thế hệ thứ nhất của bệnh nhân có DCM/HNDCM rõ ràng lẻ tẻ, ECG và siêu âm tim có thể được xem xét. [646] |

IIb |

C |

AAD: thuốc chống loạn nhịp tim; AV: nhĩ thất; CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; DCM: bệnh cơ tim giãn; ECG: điện tâm đồ; HNDCM: bệnh cơ tim giảm động không giãn giảm; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LGE: tăng cường gadolinium muộn; LVEF: phân suất tống máu thất trái; NSVT: nhịp nhanh thất tạm thời; NYHA: Hiệp hội Tim mạch New York; OMT: liệu pháp nội khoa tối ưu; PES: kích thích điện được lập trình; SCA: ngừng tim đột ngột; SCD: đột tử do tim; SD: đột tử; SMVT: nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VF: rung tâm thất; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

c Dựa trên công cụ tính nguy cơ https://lmna-risk-vta.fr/

d Xem các khuyến cáo cụ thể cho LMNA

7.1.3.2. Bệnh cơ tim thất phải gây rồi loạn nhịp

Bệnh cơ tim thất phải gây rồi loạn nhịp (Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy:ARVC) là bệnh di truyền được đặc trưng bằng thay thế cơ tim bằng xơ mỡ. [670] Tỷ lệ lưu hành phạm vi từ 1/1000 đến 1/5000 các thể, nam giới chiếm ưu thế trong số những mẫu thử. [671] Các bệnh nhân SCD / VF khi biểu hiện lần đầu tiên là người trẻ điển hình (tuổi trung bình 23 tuổi [phạm vi 13-57] so với những người biểu hiện bằng SMVT (tuổi trung bình 36 [phạm vi14-78]. [672]

ARVC được gây ra do các đột biến gây bệnh ở các gen desmosomal và ít phổ biến hơn ở các gen không desmosomal. Xét nghiệm di truyền được chỉ định và xác định đột biến (tối đa 73% mẫu thử) là tiêu chí chính để chẩn đoán. [116,671] Trong 4–16% đột biến phức hợp/digenic được tìm thấy, có liên quan đến nguy cơ gia tăng VA ở độ tuổi trẻ hơn. [672,673] Tỷ lệ xâm nhập của bệnh ở họ hàng thế hệ thứ nhất là 28–58%, [674,675] hỗ trợ việc đánh giá lâm sàng thường xuyên cho họ hàng.

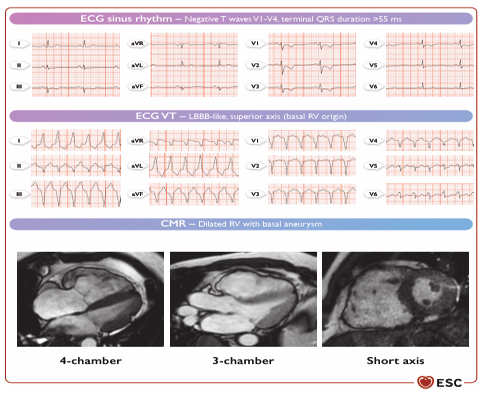

ARVC được đặc trưng bằng sự tham gia chiếm ưu thế của RV. Tiêu chí của lực lượng đặc nhiệm chẩn đoán quốc tế sửa đổi năm 2010 dựa trên chiến lược đa thông số [116] (Hình 21). Đặc tính mô bằng CMR không được đưa vào. Tuy nhiên, thâm nhiễm mỡ RV và LVLGE thường được quan sát thấy (lần lượt ở 29–53% và 35,5–45% mẫu thử) và có thể xuất hiện trước khi bệnh nhân đáp ứng các tiêu chí chẩn đoán hình ảnh chính. [676–678] Cả sự thay đổi chuyển động của thành và các bất thường tín hiệu trước/sau tương phản đều được đề xuất để nâng cao độ chính xác chẩn đoán của CMR đối với ARVC. [679] Việc xác định sự liên quan hai tâm thất và ưu thế trái ở bệnh nhân ARVC [680,681] gần đây đã dẫn đến thuật ngữ được đề xuất “bệnh cơ tim gây loạn nhịp”. [68]

Hình 21. Đặc điểm điển hình của bệnh cơ tim thất phải gây loạn nhịp liên quan đến rối loạn nhịp thất.

CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; ECG: điện tâm đồ; LBBB: block nhánh trái; RV: tâm thất phải; VT: nhịp nhanh thất. ECG sinus – Negative T waves V1-V4, terminal QRS duration > 55 ms: ECG xoang – Các song T âm ở V1-V4. Khoảng thời gian QRS kết thúc > 55 ms. Dilated RV with basal aneurysm: RV giãn với phình ở nền. chamber: buồng.

Hạn chế gắng sức cường độ cao được coi là công cụ phòng ngừa ở bệnh nhân ARVC bị ảnh hưởng lâm sàng nhằm giảm nguy cơ mắc bệnh mạch vành và tiến triển bệnh. [683–685] Việc hạn chế chơi thể thao có mang lại lợi ích cho tất cả những người mang đột biến không có biểu hiện bệnh hay không vẫn chưa được đánh giá trong các đoàn hệ tiền cứu, nhưng việc tránh tập luyện cường độ cao, cạnh tranh dường như là hợp lý. [686,687] SCD và VA xảy ra không cân xứng trong quá trình gắng sức ở những bệnh nhân bị ảnh hưởng, và truyền isoproterenol liều cao có thể gây ra PVT ở 0,90% bệnh nhân ARVC, hỗ trợ vai trò kích thích giao cảm đối với rối loạn nhịp tim. [152,688,689] Tuy nhiên, liệu thuốc chẹn beta có thể ngăn ngừa VA tự phát hay không vẫn chưa rõ ràng. Dữ liệu hạn chế cho thấy vai trò có lợi tiềm tàng của atenolol. [690]

7.1.3.2.1. Phân tầng nguy cơ

Ở những bệnh nhân ARVC không được cấy ICD, CA xảy ra ở 4,6–6,1%, trong khi 23% bệnh nhân trải qua SMVT không gây tử vong trong thời gian theo dõi trung bình 8–11 năm. [691–694]

Liệu SMVT có nguy hiểm đến tính mạng hay không phụ thuộc vào độ dài chu kỳ VT, chức năng tim và hoàn cảnh xảy ra VT. Trong số các bệnh nhân ARVC xác định / có thể xảy ra được coi là có nguy cơ VA trung gian, 23–48% sẽ được can thiệp ICD thích hợp trong thời gian theo dõi trung bình 4,7 năm. Trong 16–19% trường hợp, can thiệp ICD được kích hoạt bằng VT nhanh ≥250 lần / phút. hoặc VF, được coi là đại diện cho một biến cố đe dọa tính mạng. [695–698] Trong một nhóm lớn gồm 864 bệnh nhân ARVC (38,8% có VA trước), 43% có VT/VF trong thời gian theo dõi trung bình 5,75 năm, nhưng chỉ 10,8% là biến cố có khả năng đe dọa tính mạng. Vì vậy, ở 3 trong 4 bệnh nhân ARVC, liệu pháp ICD là phù hợp nhưng có thể không được coi là cứu sống tức thời. Điều này có liên quan vì các thuật toán và mô hình dự đoán nguy cơ dựa trên các điểm cuối rối loạn nhịp tim kết hợp, thường tương đương với các chỉ định ICD để ngăn ngừa SCD. Điều này đặc biệt quan trọng đối với những bệnh nhân ARVC trẻ tuổi có nguy cơ mắc các biến chứng liên quan đến ICD suốt đời. [695,699]

Các nghiên cứu ngẫu nhiên về điều trị ICD để phòng ngừa thứ phát còn thiếu, nhưng tỷ lệ điều trị ICD thích hợp cao được kích hoạt bằng các cơn VT/VF nhanh ở bệnh nhân được cấy sau CA hoặc VT dung nạp kém về mặt huyết động gợi ý lợi ích sống sót từ ICD. [700] Ở những bệnh nhân có VT dung nạp huyết động, lợi ích sống sót từ ICD là ít rõ ràng hơn. [691.700–702] Việc xác định bệnh nhân ARVC có nguy cơ mắc SCD là khó khăn, và bằng chứng hỗ trợ các yếu tố nguy cơ đối với VA đe dọa tính mạng là giới hạn. Ngất do loạn nhịp tim là yếu tố dự đoán cho các biến cố tiếp theo ở hầu hết loạt bệnh nhân mắc ARVC rõ ràng (HR gộp 3,67; CI 2,75–4,9) [81.696.701.703] và ở những bệnh nhân này, nên xem xét ICD. Rối loạn chức năng RV và LV có liên quan đến nguy cơ rối loạn nhịp tim cao hơn. [675,704] Các giá trị ngưỡng rất khó xác định, nhưng ở những bệnh nhân bị rối loạn chức năng RV nặng (thay đổi diện tích phân số RV ≤17% hoặc phân suất tống máu RV ≤35%), nên xem xét sử dụng ICD. Tương tự như vậy, bệnh nhân ARVC có tổn thương LV đáng kể (LVEF ≤ 35%) nên được điều trị theo khuyến cáo DCM hiện hành về cấy ICD. Có dữ liệu mâu thuẫn về giá trị tiên đoán độc lập của NSVT đối với các biến cố loạn nhịp dai dẳng tiếp theo. [695,696,701] Tương tự như vậy, vai trò của PES trong phân tầng nguy cơ, đặc biệt ở những bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng, chưa được xác định rõ ràng. [695,696,705] Trong một loạt bài bao gồm chủ yếu là các bệnh nhân có triệu chứng, cả NSVT và PES dương tính đều dự đoán độc lập các biến cố loạn nhịp tim, trong khi các loạt khác báo cáo độ chính xác chẩn đoán thấp. [696] Dự đoán nguy cơ dựa trên một tham số duy nhất không xem xét tác động kết hợp tiềm ẩn và tương tác giữa các yếu tố. Do đó, mặc dù thiếu dữ liệu hỗ trợ, nhóm chuyên gia này ủng hộ nên xem xét cấy ICD [706] ở bệnh nhân ARVC có triệu chứng với rối loạn chức năng RV vừa phải (< 40%) và/hoặc LV (< 45%) và những người có NSVT hoặc có thể tạo ra SMVT trong PES. Một mô hình nguy cơ được xác nhận mang tính nội khoa gần đây đã được phát triển từ 528 bệnh nhân có ARVC xác định và không có VA trước đó, bao gồm tuổi, giới tính, ngất do loạn nhịp, NSVT, gánh nặng PVC, các chuyển đạo có sóng T đảo ngược và phân suất tống máu RV, để dự đoán bất kỳ VA dai dẳng nào (c- index 0,77). [81] Ngoài ra, một mô hình dự đoán cho VA cụ thể đe dọa tính mạng đã được quảng bá dựa trên 864 bệnh nhân ARVC, với các yếu tố dự đoán gồm giới tính nam, tuổi, số lượng PVC 24 giờ và các chuyển đạo sóng T đảo ngược (c-index 0,74). [702] Tuy nhiên, cần có các nghiên cứu xác nhận trước khi các mô hình nguy cơ này có thể được khuyến cáo sử dụng trên lâm sàng.

7.1.3.2.2. Điều trị

Có tới 97,4% tổng số các cơn VA ở người nhận ARVC mang ICD là SMVT. Tỷ lệ cắt cơn rất cao tính theo ATP (92% tổng số cơn) không phụ thuộc vào độ dài chu kỳ VT hỗ trợ mạnh mẽ cho các thiết bị có khả năng ATP. [698] S-ICD (Subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator) làm giảm các biến chứng liên quan đến điện cực và đã được chứng minh là có hiệu quả gây sốc cắt các VA ở các nhóm nhỏ bệnh nhân ARVC trong thời gian theo dõi ngắn hạn. [707]

Điều trị bổ sung thường được đòi hỏi để ức chế VA. Mặc dù dữ liệu lâm sàng chưa được xác nhận nhưng thuốc chẹn beta được khuyến cáo là liệu pháp đầu tiên ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng.

Dữ liệu về AAD để ngăn ngừa VT tái phát được giới hạn ở các nghiên cứu quan sát và đăng ký nhỏ. Nhìn chung, liệu pháp AAD có hiệu quả hạn chế. Mặc dù sotalol có hiệu quả trong việc ngăn ngừa khả năng tạo ra VT, [708] nó không ức chế được chứng rối loạn nhịp tim có ý nghĩa lâm sàng. [690,708] Điều trị bằng amiodarone hoặc thuốc nhóm 1 có liên quan đến xu hướng tái phát VT thấp hơn so với sotalol. [709] Việc bổ sung flecainide vào thuốc chẹn beta / sotalol có lợi trong một nhóm thuần tập nhỏ. [710] Triệt phá qua catheter cung cấp một giải pháp thay thế. Triệt phá chất nền thượng tâm mạc và nội tâm mạc bổ trợ, nếu cần, có liên quan đến khả năng sống sót thoát khỏi VT đầy hứa hẹn. Những nguy cơ tiềm ẩn về thủ tục, tác dụng phụ của thuốc và sở thích của bệnh nhân cần được xem xét. [482]

Bảng khuyến cáo 29 — Khuyến cáo cho chẩn đoán, phân tầng nguy cơ, ngăn ngừa đột tử tim, và điều trị rồi loạn nhịp thất trong bệnh cơ tim thất phải gây rối loạn nhịp

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Đánh giá chẩn đoán và khuyến cáo chung | ||

| Ở những bệnh nhân nghi ngờ ARVC, CMR được khuyến cáo. [676–678] | I | B |

| Ở những bệnh nhân nghi ngờ hoặc chẩn đoán xác định ARVC, nên tư vấn và xét nghiệm di truyền. [672,673] | I | B |

| Tránh gắng sức cường độ cao được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán xác định ARVC. [683–685] | I | B |

| Việc tránh gắng sức cường độ cao có thể được xem xét ở những người mang đột biến gây bệnh liên quan đến ARVC và không có kiểu hình. [683,687] | IIb | C |

| Điều trị chẹn beta có thể được xem xét ở tất cả các bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán xác định ARVC. | IIb | C |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ và phòng ngừa SCD tiên phát | ||

| Cấy ICD nên được cân nhắc ở những bệnh nhân có ARVC xác định và ngất do rối loạn nhịp tim. [696,701,711–713] | IIa | B |

| Cấy ICD nên được cân nhắc ở những bệnh nhân ARVC xác định và rối loạn chức năng tâm thu RV hoặc LV nặng. [675,691] | IIa | C |

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng với ARVC xác định, rối loạn chức năng thất phải hoặc trái vừa phải, và NSVT hoặc không thể tạo ra SMVT ở PES. [695,696,701,703,705] | IIa | C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân ARVC và các triệu chứng rất nghi ngờ VA, PES có thể được xem xét để phân tầng nguy cơ. [695,705] | IIb | C |

| Dự phòng SCD thứ phát và điều trị VAs | ||

| Cấy ICD được khuyến cáo ở bệnh nhân ARVC với VT hoặc VF không dung nạp về mặt huyết động. [700] | I | C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân mắc ARVC và VA tạm thời hoặc dai dẳng, nên điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn beta. | I | C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân ARVC và SMVT có triệu chứng, tái phát hoặc ICD phát sốc, mặc dù đã dùng thuốc chẹn beta, triệt phá qua catheter ở các trung tâm chuyên sâu nên được xem xét. [482,709,714] | I | C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân ARVC có chỉ định cấy ICD, nên xem xét một thiết bị có khả năng lập trình ATP cho SMVT với tần số cao. [698] | IIa | C |

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân ARVC có SMVT dung nạp huyết động. [692] | IIa | C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân ARVC và VT có triệu chứng tái phát, mặc dù đã dùng thuốc chẹn beta, điều trị AAD nên được xem xét. [709,710] | IIa | C |

| Quản lý thân nhân bệnh nhân ARVC | ||

| Ở các người thân thế hệ thứ nhất của bệnh nhân ARVC, điện tâm đồ và siêu âm tim được khuyến cáo. [675] | I | C |

AAD: thuốc chống loạn nhịp tim; ARVC: bệnh cơ tim thất phải gây loạn nhịp; ATP: tạo nhịp tim chống nhịp nhanh; CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; ECG: điện tâm đồ; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LV: tâm thất trái; NSVT: nhịp nhanh thất tạm thời; PES: kích thích điện được lập trình; RV: tâm thất phải; SCD: đột tử do tim; SMVT: nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

b Class khuyến cáo.

c Hướng dẫn ESC năm 2020 về tim mạch thể thao và gắng sức ở bệnh nhân mắc bệnh tim mạch. [4]

d Tiền ngất hoặc đánh trống ngực gợi ý VA

7.1.3.3. Bệnh cơ tim phì đại (HCM)

HCM được đặc trưng bởi sự tăng độ dày thành LV mà không giải thích được bằng tình trạng tải trọng bất thường (chẳng hạn như tăng huyết áp hoặc bệnh van tim). [128,715] Do bệnh sử tự nhiên và cách quản lý khác nhau tùy theo nguyên nhân cơ bản của LVH, việc chẩn đoán là hết sức quan trọng (xem Phần 7.1.3.5) và bao gồm CMR và xét nghiệm di truyền. [716–725] HCM thường được gây ra do đột biến di truyền trội trên nhiễm sắc thể thường, hỗ trợ sàng lọc tim ở những người thân thế hệ thứ nhất, song song với xét nghiệm di truyền ở bệnh nhân đầu tiên. Đột biến gen sarcomeric được xác định ở 30–60%, thường gặp nhất ở những bệnh nhân trẻ hơn khi được chẩn đoán hoặc có tiền sử gia đình mắc bệnh HCM. [646,722]

Tỷ lệ mắc bệnh HCM ước tính ở người lớn là 1 trên 500. [726] Ở trẻ em, tỷ lệ này thấp hơn nhiều.

Tỷ lệ tử vong hàng năm liên quan đến HCM là 1–2% trong hầu hết các nghiên cứu với các chiến lược quản lý hiện đại, [128,715] và có thể thấp tới 0,5%. [727] Tỷ lệ SCD hoặc liệu pháp ICD thích hợp hàng năm là khoảng 0,8% nhưng phần lớn phụ thuộc vào tuổi và hồ sơ nguy cơ. [85,728–730] Bệnh nhân HCM có nguy cơ bị suy tim, rung nhĩ và đột quỵ. [128,715] Hầu hết các trường hợp tử vong liên quan đến HCM ở độ tuổi dưới 60 tuổi đều xảy ra đột ngột, trong khi bệnh nhân lớn tuổi tử vong thường xuyên hơn vì đột quỵ hoặc suy tim. [731] SCD thường liên quan đến VA, có thể là hậu quả của thiếu máu cục bộ, tắc nghẽn đường ra thất trái (LVOT), hoặc rối loạn nhịp trên thất. SCD cũng có thể được kích hoạt do tập thể dục và việc tham gia các môn thể thao cạnh tranh không được khuyến khích. [732] Tuy nhiên, dữ liệu gần đây cho thấy ngay cả việc gắng sức mạnh mẽ ở bệnh nhân HCM không có dấu hiệu nguy cơ cũng có thể không liên quan đến VA. [733,734]

7.1.3.3.1. Phân tầng nguy cơ và ngăn ngừa đột tử tim tiên phát.

Trong phòng ngừa tiên phát, thách thức vẫn là xác định nhóm tương đối nhỏ bệnh nhân có nguy cơ SCD cao nhất. NSVT được xác định bằng theo dõi ECG liên tục (24/48h) ở 20–25% bệnh nhân. [128,715] Tỷ lệ lưu hành của NSVT tăng theo tuổi và tương quan với độ dày thành LV và LGE trên CMR. [716–721,735] Giá trị tiên lượng của NSVT đối với SCD là quan trọng hơn ở bệnh nhân trẻ (< 30 tuổi). [735] Mối quan hệ giữa thời gian, tần suất hoặc tỷ lệ NSVT và tiên lượng HCM vẫn chưa rõ ràng. [735]

NSVT được ghi nhận trong test gắng sức là rất hiếm, nhưng có liên quan đến nguy cơ SCD cao hơn. [732] Các yếu tố nguy cơ bổ sung đã được xác định và điểm phân tầng nguy cơ SCD 5 năm dựa trên bảy yếu tố (tuổi, độ dày thành LV, kích thước LA, độ dốc LVOT, NSVT, ngất không giải thích được và tiền sử gia đình về SCD) đã được phát triển [732] 85] (HCM Risk-SCD: https://doc2do.com/hcm/web HCM.html) và được xác nhận bên ngoài. [85,728,729] Máy tính không được thiết kế để sử dụng cho các vận động viên ưu tú, hoặc những người mắc các bệnh về chuyển hóa hoặc thâm nhiễm, hoặc sau phẫu thuật cắt bỏ cơ hoặc triệt phá vách bằng alcohol. [85]

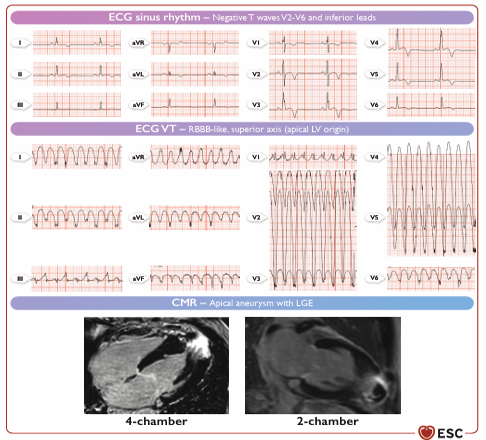

Các yếu tố bổ sung không được mô hình Nguy cơ – SCD nắm bắt cũng nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ được tính toán ở mức trung bình hoặc thấp, gồm rối loạn chức năng tâm thu LV, chứng phình mỏm, LGE lan rộng trên CMR và sự hiện diện của một hoặc nhiều đột biến sarcomeric (Hình 22). [716,717,722,736–739] LGE lan rộng trên CMR được xác định là ≥15% khối lượng LV đã được đề xuất là yếu tố dự báo tốt về SCD ở người lớn. Tuy nhiên, các ngưỡng có thể khó sử dụng vì việc định lượng LGE phụ thuộc vào việc thu nhận CMR, loại và mức độ tương phản.

Đánh giá lại định kỳ là bắt buộc như một phần của đánh giá theo chiều dài của bệnh nhân. VA do PES gây ra được coi là không đặc hiệu, mặc dù đã có báo cáo các kết quả trái ngược nhau. [740,741]

Hình 22. Đặc điểm điển hình của bệnh cơ tim phì đại liên quan đến nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng.

CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; ECG: điện tâm đồ; LGE: tăng cường gadolinium muộn; LV: thất trái; RBBB: block nhánh phải; VT: nhịp nhanh thất. ECG sinus – Negative T waves V1-V4 and inferior leads: ECG xoang – Các sóng T âm ở V1-V4 và các chuyển đạo dưới. Apical aneurysm with LGE: Phình mỏm với gia tang galodium trễ. chamber: buồng.

Ở trẻ em, có rất ít dữ liệu về phòng ngừa tiên phát cho đến khi có sự phát triển gần đây về điểm số và các công cụ tính toán nguy cơ liên quan. [83,84] Điểm số Nguy cơ – Trẻ em trong HCM [84] đã được phát triển và xác thực mang tính bên ngoài [742] đặc biệt ở trẻ em mắc HCM (1–16 tuổi) và gồm ngất không giải thích được, độ dày thành LV tối đa, đường kính nhĩ trái lớn , độ dốc LVOT thấp và NSVT (https://hcmriskkids.org). Ngược lại với người lớn, gồm cả tuổi và tiền sử gia đình về SCD không cải thiện hiệu suất của mô hình nhi khoa. Những bệnh nhân có VF trước đó hoặc VT dai dẳng, các lỗi chuyển hóa bẩm sinh đã biết và các nguyên nhân hội chứng của HCM đã được loại trừ. Giá trị tiên đoán của LGE ở trẻ em ít được xác định rõ ràng, mặc dù dữ liệu sơ bộ đã được báo cáo. [74]

7.1.3.3.2. Điều trị để ngăn ngừa tái phát rối loạn nhịp thất.

Bệnh nhân sống sót sau CA do VT/VF hoặc VT không dung nạp về mặt huyết động vẫn có nguy cơ cao bị VA đe dọa tính mạng trong tương lai và sẽ được hưởng lợi từ liệu pháp ICD. [128,744–746]

Không có RCT nào trong HCM hoặc nghiên cứu đoàn hệ hỗ trợ vai trò quan trọng của thuốc trong phòng ngừa SCD. [128,715,747] Amiodarone có thể làm giảm VA nhưng có kết quả trái ngược nhau về phòng ngừa SCD. [747,748] Disopyramide và thuốc chẹn beta có hiệu quả để kiểm soát các triệu chứng và tắc nghẽn LVOT, nhưng không có bằng chứng nào cho thấy chúng làm giảm nguy cơ SCD. [128,715] Tương tự, phẫu thuật cắt bỏ cơ hoặc triệt phá bằng alcohol không được khuyến cáo với mục đích giảm nguy cơ SCD ở bệnh nhân tắc nghẽn LVOT. [128,715] Sau khi cấy ICD để phòng ngừa tiên phát hoặc thứ phát, phân nhóm VA được ghi nhận phổ biến nhất là SMVT, và ATP thành công trong 69–76,5% trong tất cả các giai đoạn. [749–751] Mặc dù thiếu dữ liệu về hiệu quả của thuốc, AAD (thuốc chẹn beta, amiodarone, sotalol, thuốc chẹn kênh natri) nên được xem xét ở bệnh nhân HCM có VA có triệu chứng. Triệt phá qua catheter cũng có thể được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân HCM được chọn lọc kỹ với SMVT, trong đó AAD không hiệu quả, chống chỉ định hoặc không dung nạp, do kết quả sau khi triệt phá kém hơn so với các nguyên nhân không do thiếu máu cục bộ khác. [752–754]

Bảng khuyến cáo 30 — Các khuyến cáo phân tầng nguy cơ, ngăn ngừa đột tử tim và điều trị rối loạn nhịp thất trong bệnh cơ tim phì đại

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Đánh giá chẩn đoán và các khuyến cáo chung | ||

| CMR với LGE được khuyến cáo ở bệnh nhân HCM để chẩn đoán.[716–718] | I | B |

| Tư vấn và xét nghiệm di truyền được khuyến cáo ở bệnh nhân HCM. [721–725] | I | B |

| Việc tham gia luyện tập cường độ cao có thể được xem xét đối với bệnh nhân HCM trưởng thành không có triệu chứng và không có dấu hiệu nguy cơ. [733] | IIb | C |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ và ngăn ngừa SCD tiên phát | ||

| Đánh giá nguy cơ SCD trong 5 năm được đánh giá ở lần đánh giá đầu tiên và ở khoảng thời gian 1-3 năm hoặc khi có sự thay đổi về tình trạng lâm sàng được khuyến cáo. | I | C |

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân từ 16 tuổi trở lên với ước tính nguy cơ SD trong 5 năm ≥6%.c, [85,728,729] | IIa | B |

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở bệnh nhân HCM từ 16 tuổi trở lên với nguy cơ SCD trung bình 5 năm (≥4 đến > 6%) c và với (a) LGE đáng kể trên CMR (thường ≥15% khối lượng LV); hoặc (b) LVEF < 50%; hoặc (c) phản ứng huyết áp bất thường trong quá trình thử nghiệm gắng sứcd; hoặc (d) phình mỏm LV; hoặc (e) sự hiện diện của đột biến gây bệnh sarcomeric. [716,717,722,736–739] | IIa | B |

| Ở trẻ em dưới 16 tuổi bị HCM và ước tính nguy cơ SD trong 5 năm ≥6% (dựa trên thang điểm nguy cơ HCM-Kidse), nên cân nhắc cấy ICD. [84,742] | IIa | B |

| Cấy ICD có thể được xem xét ở bệnh nhân HCM từ 16 tuổi trở lên với ước tính nguy cơ SCD trong 5 năm từ ≥4 đến ,6%.c, [85,728,729] | IIb | B |

| Cấy ICD có thể được xem xét ở bệnh nhân HCM từ 16 tuổi trở lên với nguy cơ SCD 5 năm ước tính thấp (,4%) c và với (a) LGE đáng kể trên CMR (thường ≥15% khối lượng LV); hoặc (b) LVEF < 50%; hoặc (c) phình mỏm LV. [716,717,722,736–739] | IIb | B |

| Ngăn ngừa SCD và điều trị VAs | ||

| Khuyến cáo cấy ICD ở các bệnh nhân HCM có VT không dung nạp huyết động hoặc V.F. [744–746] | I | B |

| Ở bệnh nhân HCM biểu hiện với SMVT dung nạp huyết động, ICD

cấy ghép nên được xem xét. |

IIa | C |

| Ở bệnh nhân HCM và VA tái phát, có triệu chứng, hoặc liệu pháp ICD tái phát, điều trị AAD nên được xem xét. | IIa | C |

| Triệt phá qua catheter ở các trung tâm chuyên khoa có thể được được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân được chọn với HCM và SMVT có triệu chứng, tái phát hoặc ICD sốc cho SMVT, ở họ AAD không hiệu quả, chống chỉ định, hoặc không dung nạp. [753,754] |

IIb |

C |

| Quản lý người thân của các bệnh nhân HCM | ||

| Khuyến cáo là ECG và siêu âm tim cho thân nhân thế hệ thứ nhất của bệnh nhân HCM. | I | C |

AAD: thuốc chống loạn nhịp tim; CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; ECG:

điện tâm đồ; HCM: bệnh cơ tim phì đại; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LGE: tăng cường gadolinium muộn; LV: tâm thất trái; LVEF:

Phần phân suất tống máu thất trái; SCD: đột tử do tim; SD: đột tử;

SMVT: nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất;

VF: rung tâm thất; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

c Dựa trên nguy cơ SCD trong HCM: https://doc2do.com/hcm/webHCM.html

d Được định nghĩa là không tăng được huyết áp tâm thu ít nhất 20 mmHg từ lúc nghỉ đến khi đạt đỉnh gắng sức, hoặc giảm 0,20 mmHg so với áp suất đỉnh.

e Dựa trên thang điểm nguy cơ trẻ em HCM: https://hcmriskkids.org

7.1.3.4. Bệnh thất trái không đông đặc Left ventricular non-compaction

Bệnh thất trái không đông đặc (left ventricular non – compaction: LVNC) gồm một nhóm bệnh không đồng nhất. Việc chẩn đoán là một thách thức và nhiều tiêu chuẩn chẩn đoán khác nhau đã được đề xuất. Hiệu suất xét nghiệm di truyền ở chỉ số bệnh nhân là thấp. [755]

Kiểu hình hình thái không nén dựa trên các thông số hình ảnh cũng có thể xuất hiện ở quần thể khỏe mạnh. [756] Một phân tích tổng hợp gồm 2501 bệnh nhân LVNC cho thấy nguy cơ tử vong do tim mạch tương tự như bệnh nhân DCM, không liên quan đến mức độ bề dầy (trabeculation).[757] Phát hiện xơ hóa khu trú dựa trên CMR bằng LGE trong LVNC với khả năng tống máu được bảo tồn có liên quan đến các biến cố tim nghiêm trọng (tử vong do sảy thai, điều trị bằng ICD, ghép tim [HTX]/LVAD) trong một phân tích tổng hợp khác bao gồm 574 bệnh nhân (OR 6.1; CI 2.1– 17,5;P , 0,001).[758] Sự kết hợp của tiêu chí CMR với kiểu gen có hệ thống có thể khắc phục được những điều không chắc chắn hiện tại về phân tầng nguy cơ.[759]

Bảng khuyến cáo bảng 31 — Khuyến cáo cầy máy khử rung tim trong bệnh thất trái không đông đặc

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh cơ tim LVNC kiểu hình dựa trên CMR hoặc siêu âm tim, cấy ICD để phòng ngừa tiên phát SCD nên được xem xét tuân theo khuyến cáo như bệnh DCM/ HNDCM. |

IIa |

C |

CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; DCM: bệnh cơ tim giãn; HNĐCM: bệnh cơ tim giảm động không giãn; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LVNC: không đông đặc thất trái; SCD: đột tử do tim.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng

Kiểu hình của bệnh cơ tim hạn chế (Restrictive cardiomyopathy: RCM) rất hiếm và có thể là hậu quả của nhiều nguyên nhân khác nhau, gồm các rối loạn thâm nhiễm (ví dụ bệnh amyloidosis) và bệnh dự trữ (ví dụ bệnh Andersen–Fabry), việc xác định bệnh này là rất quan trọng để hướng dẫn điều trị. Suy tim là một trong những triệu chứng hàng đầu trong RCM nguyên phát và thứ phát. [760]

Trong bệnh Fabry, phần lớn các trường hợp tử vong do tim mạch được báo cáo đã được phân loại là SCD trong tổng quan hệ thống gần đây của 13 nghiên cứu bao gồm 4185 bệnh nhân. [761] Tuổi cao hơn, giới tính nam, LVH, LGE và NSVT đã được xác định là các yếu tố nguy cơ tiềm ẩn liên quan đến các biến cố SCD. Tuy nhiên, tỷ lệ SCD được báo cáo chỉ ở 11 nghiên cứu, bao gồm 623 bệnh nhân. Bản chất hồi cứu, quan sát của hầu hết các nghiên cứu nhỏ, đơn trung tâm này và số tử vong do tim mạch thấp (36/623) và SCD (30/623) hiện không cho phép hướng dẫn cấy ICD phòng ngừa tiên phát. [761]

Bệnh amyloidosis có thể được gây ra do các protein tiền thân không được gấp nếp khác nhau dẫn đến sự lắng đọng trong mô và các cơ quan. Bệnh amyloid tim chủ yếu liên quan đến amyloid chuỗi nhẹ hoặc amyloid transthyretin. Loại thứ hai có thể được chia thành loại hoang dã, còn được gọi là amyloid tuổi già, thường phức tạp hơn do chậm dẫn truyền AV và rối loạn nhịp nhĩ, và amyloid do đột biến gây bệnh ở gen TTR. Biểu hiện của bệnh phụ thuộc vào đột biến. Bất chấp những tiến bộ trong điều trị bệnh amyloidosis chuỗi nhẹ, kết quả vẫn còn thấp ở những bệnh nhân có biểu hiện liên quan đến tim. [762] Nguyên nhân tử vong là suy tim tiến triển, rối loạn chức năng thần kinh tự động, và phân ly điện cơ. [762,763] Lợi ích của việc cấy ICD phòng ngừa tiên phát ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh amyloidosis tim là không chắc chắn. Hiện tại, ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có VT không dung nạp về mặt huyết động sau khi thảo luận cẩn thận về các nguy cơ tranh chấp giữa tử vong không do loạn nhịp và tử vong không do tim.

Bảng khuyến cáo 32 — Các khuyến cáo cấy máy khử rung tim ở các bệnh nhân bệnh amyloidosis tim

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có amyloidosis chuỗi nhẹ hoặc liên quan đến transthyretin bệnh amyloidosis tim và VT huyết động không dung nạp được. |

IIa |

C |

ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

a Class khuyến cáo

b Mức độ bằng chứng

7.1.3.6. Rối loạn thần kinh cơ

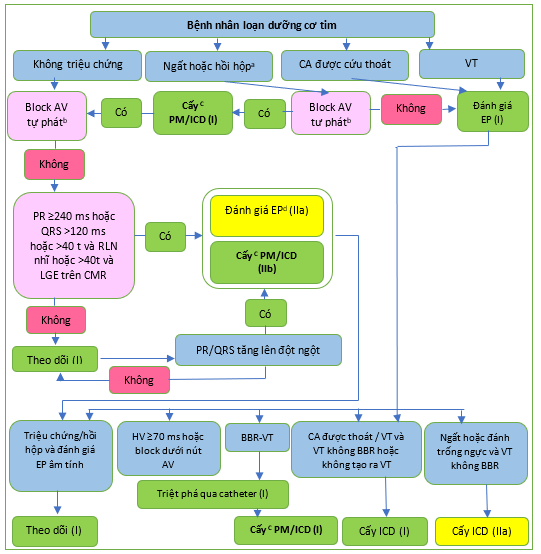

Sơ đồ phân tầng nguy cơ, phòng ngừa SCD và điều trị VA trong bệnh loạn dưỡng cơ được trình bày trong Hình 23.

Hình 23. Thuật toán phân tầng nguy cơ, phòng ngừa đột tử do tim và điều trị rối loạn nhịp thất trong bệnh loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ.

Hình 23. Thuật toán phân tầng nguy cơ, phòng ngừa đột tử do tim và điều trị rối loạn nhịp thất trong bệnh loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ.

AV: nhĩ thuất; BBR-VT: nhịp nhanh thất vào lại bó nhánh; CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; EP: nghiên cứu điện sinh lý xâm lấn; HV: Khoảng cách từ His đến thất; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LGE: gadolinium tăng cường muộn; N: Không; VT: nhịp nhanh thất, Y, Có. a Ngất hoặc đánh trống ngực rất nghi ngờ nguồn gốc rối loạn nhịp tim. b Block AV tự phát: block AV độ 3 hoặc độ 2 cao cấp.

Các yếu tố ủng hộ việc cấy ICD: tuổi, [5,6,11] sự mở rộng CTG, [6–9,13,16] đột tử (SD) hoặc tiền sử gia đình mắc SD, [5] bất thường dẫn truyền ECG, [16] PR kéo dài, [13] block nhánh trái, [5] rối loạn nhịp nhĩ, [6,16] VT tạm thời, [5] rối loạn chức năng LV, [17] LGE đáng kể trong CMR. [14,15,18] d Tiếp tục quản lý theo kết quả đánh giá EP.

Chứng loạn nhịp tim thường gặp và thường là biểu hiện đầu tiên của rối loạn thần kinh cơ. [764] Chứng loạn dưỡng cơ là chứng loạn dưỡng cơ phổ biến nhất ở người trưởng thành (tỷ lệ mắc là 1 trên 8000). Chứng loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ là hậu quả của sự mở rộng lặp lại trinucleotide ở phần cuối của gen DMPK, dẫn đến việc ghép sai SCN5A và làm chậm hệ thống dẫn truyền tim và rối loạn nhịp tim. Bệnh loạn dưỡng Duchenne cũng có tỷ lệ mắc cao (1 trên 3500 ca bé trái sinh). Vì hầu hết bệnh nhân chết trước 20 tuổi nên hiếm khi xảy ra ở tuổi trưởng thành. Các rối loạn thần kinh cơ khác, chẳng hạn như bệnh loạn dưỡng Becker (1 trên 100.000 ca sinh con trai) và bệnh loạn dưỡng cơ mặt vai (1 trong 100.000), ít gặp hơn. Hầu hết các rối loạn này có liên quan đến rối loạn dẫn truyền và nhịp tim, một số đe dọa tính mạng và có cơ chế phù hợp với liệu pháp chống loạn nhịp cụ thể. [17] Nên cân nhắc điều trị chống loạn nhịp tim vì chức năng cơ bắp và tuổi thọ thường chỉ bị giới hạn ở mức độ vừa phải. [765] Thông thường nên điều trị những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh thần kinh cơ sống sót sau CA hoặc có VA hoặc rối loạn chức năng tâm thất theo cách tương tự như những bệnh nhân không có biểu hiện ngoài tim. Tuy nhiên, lợi ích của việc cấy ICD phải được cân bằng với tiên lượng chung ở một số phân nhóm, chẳng hạn như chứng loạn dưỡng Duchenne.

Các triệu chứng có thể là kết quả của nhịp tim chậm hoặc nhịp tim nhanh và cần phải đánh giá điện sinh lý xâm lấn trừ khi có nguyên nhân, chẳng hạn như block AV, đã được ghi nhận trên lâm sàng. [153] Sự gia tăng đột ngột khoảng PR và thời gian QRS có liên quan đến block AV và SCD trong chứng loạn dưỡng cơ mặc dù không có triệu chứng và nên xem xét đánh giá điện sinh lý. [766,767] Khoảng HV ≥70 ms sẽ nhắc nhở việc cấy máy tạo nhịp tim bất kể triệu chứng. Việc tạo ra BBR-VT ở bệnh nhân có triệu chứng ủng hộ mạnh mẽ BBR-VT (ESC CardioMed chương 42.5) [768] như một nguyên nhân cơ bản của các triệu chứng và khuyến cáo triệt phá nhánh phải. [153] Sau khi triệt phá nhánh bó, nguy cơ block AV khi theo dõi được coi là đặc biệt cao do bệnh His–Purkinje tiến triển và cần phải cấy máy tạo nhịp tim. Khoảng PR hoặc QRS kéo dài, [13,16,80] rối loạn nhịp nhĩ đồng thời, [6,16,80] và LGE trong CMR [14,15,18] ở bệnh nhân trên 40 tuổi đều có liên quan đến block AV và SCD trong theo dõi trong chứng loạn dưỡng cơ. Theo đó, việc cấy máy tạo nhịp tim có thể được xem xét ngay cả khi không có triệu chứng. Mặc dù thiếu dữ liệu, việc cấy ICD thay vì máy tạo nhịp tim có thể được ưu tiên ở bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng cơ, với các yếu tố nguy cơ bổ sung cho VA và SCD (Hình 23). Cấy máy tạo nhịp tim vĩnh viễn cũng có thể được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân mắc hội chứng Kearns–Sayre, Emery–Dreiffus, hoặc loạn dưỡng cơ vùng chi – gốc chi (limb-girdle) với bất kỳ mức độ block nhĩ thất nào vì nguy cơ đáng kể tiến triển nhanh chóng thành block toàn bộ. Ở những bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng cơ chi- gốc chi type 1B hoặc loạn dưỡng cơ Emery–Dreifuss có chỉ định tạo nhịp hoặc LGE đáng kể trên CMR, nên xem xét cấy ICD. [769]

Cấy ICD thay vì máy tạo nhịp tim cũng có thể được xem xét ở bệnh nhân Duchenne/Becker, khi có LGE đáng kể trên CMR. [770,771] Tuy nhiên, tiên lượng chung của những bệnh này cần được xem xét. Ở những bệnh nhân sống sót sau CA do SMVT, cấy ICD được khuyến cáo khi các VT khác ngoài BBR-VT (ví dụ: VT liên quan đến sẹo) có thể tạo ra được hoặc nếu VT không thể tạo ra được. Bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ có ngất có thể do VA, ngay cả khi không tạo ra được, và những người có đánh trống ngực và tạo ra không phải BBR-VT được coi là có nguy cơ mắc SCD do loạn nhịp, và ICD nên được xem xét.

Do tính chất tiến triển, nên theo dõi ECG hàng năm, ngay cả trong giai đoạn tiềm ẩn của bệnh khi bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng và ECG bình thường. [6,13] Do tiến triển chậm và thực tế là những thay đổi đáng kể thường được phản ánh trên ECG bề mặt, đánh giá điện sinh lý nối tiếp để đánh giá dẫn truyền AV và tạo ra rối loạn nhịp tim không được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân không nghi ngờ rối loạn nhịp hoặc tiến triển rối loạn dẫn truyền ECG. [767,772]

Bảng khuyến cáo 33 – Khuyến cáo về phân tầng nguy cơ, phòng ngừa đột tử do tim và điều trị rối loạn nhịp thất trong các bệnh thần kinh cơ

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Các khuyến cáo chung | ||

| Theo dõi hàng năm với ít nhất một ECG 12 chuyển đạo được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân bị bệnh loạn dưỡng cơ, ngay cả trong giai đoạn tiềm ẩn của bệnh. [6,13] |

I |

C |

| Người ta khuyến cáo những bệnh nhân bị rối loạn thần kinh cơ có VA hoặc rối loạn chức năng tâm thất được điều trị theo cách tương tự cách điều trị rối loạn nhịp tim cho bệnh nhân không có rối loạn thần kinh cơ. [17,765] |

I |

C |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ, dự phòng SCD tiên phát và thứ phát | ||

| Đánh giá điện sinh lý xâm lấn được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân bị loạn dững trương lực cơ và đánh trống ngực hoặc ngất gợi ý VA hoặc sống sót sau CA.[153] |

I |

C |

| Cấy ICD được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ và SMVT hoặc CA được thoát không do BBR-VT gây ra. [766[ |

I |

C |

| Đánh giá điện sinh lý xâm lấn nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân mắc chứng loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ và tăng khoảng PR hoặc thời gian QRS đột ngột.[766,767] |

IIa |

B |

| Đánh giá điện sinh lý xâm lấn nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân mắc chứng loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ và khoảng PR ≥240 ms hoặc thời gian QRS ≥120 ms hoặc những người trên 40 tuổi và bị rối loạn nhịp trên thất hoặc những người trên 40 tuổi và có LGE đáng kể trên CMR.c , [5,14,16,766] |

IIa |

B |

| Ở bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng cơ không có AV chậm dẫn truyền và ngất rất đáng nghi ngờ đối với VA, nên xem xét cấy ICD. [766] |

IIa |

C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ có đánh trống ngực rất nghi ngờ VA và gây ra non-BBR-VT, cấy ICD nên được xem xét. [766] |

IIa |

C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân mắc chứng loạn dưỡng cơ chi-vòng lưng (girdle) type 1B hoặc Emery– Dreifuss và có chỉ định tạo nhịp, nên cân nhắc cấy ICD.[769] |

IIa |

C |

| Cấy ICD có thể được xem xét ở bệnh nhân bị cơ Duchenne/Becker chứng loạn dưỡng và LGE đáng kể trong CMR.[770,771] |

IIb |

C |

| Cấy ICD hơn máy tạo nhịp vĩnh viễn có thể được xem xét ở bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng trương lực cơ với nhiều yếu tố nguy cơ bổ xung d đối với VA và SCD. |

IIb |

C |

| Ở bệnh nhân loạn dưỡng cơ, đánh giá điện sinh lý một loạt dẫn truyền AV và tạo ra rối loạn nhịp tim không được khuyến cáo nếu không có nghi ngờ rối loạn nhịp tim hoặc tiến triển rối loạn dẫn truyền ECG.[772] |

III |

C |

| Quản lý VA | ||

| Ở những bệnh nhân BBR-VT có triệu chứng, triệt phá qua catheter được khuyến cáo.e, [153,474,475,477] | I | C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân bị loạn dưỡng cơ trải qua triệt phát BBR-VT, cấy máy tạo nhịp/ICD được khuyến cáo. [153] | I | C |

AV: nhĩ thất; BBR-VT: nhịp nhanh thất vào lại bó nhánh; CA: ngừng tim; CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; ECG: điện tâm đồ; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LBBB: block nhánh bỏ trái; LGE: gadolinium gia tăng muộn; LV: thất trái; SCD: đột tử do tim; SD: đột ngột; SHD, bệnh tim cấu trúc; SMVT, nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng; VA, rối loạn nhịp thất; VT, nhịp nhanh thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

c Mức độ bằng chứng C.

d Các yếu tố ủng hộ việc cấy ICD: Tuổi, [5,6,11] CTG mở rộng, [6–9,13,16] SD hoặc tiền sử gia đình SD, [5] bất thường dẫn truyền ECG, [16] PR kéo dài, [13] LBBB, [5 ] loạn nhịp nhĩ, [6,16] VT tạm thời, [5] rối loạn chức năng LV, [17] bất thường cấu trúc trên

CMR. [14,15,18]

e Trong các tình trạng tim khác (ví dụ như thay van động mạch chủ) bằng BBR-VT, triệt phá qua catheter được khuyến cáo.

(Còn nữa…)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

- Connolly SJ, Hallstrom AP, Cappato R, Schron EB, Kuck KH, Zipes DP, et al. Meta-analysis of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator secondary prevention trials. AVID, CASH and CIDS studies. Antiarrhythmics vs Implantable Defibrillator study. Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg. Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study. Eur Heart J2000; 21: 2071–2078.

- Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, DaubertJP, Higgins SL, KleinH, etal. Improved survival with animplanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1933–1940.

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, etal. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillat or in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl JMed2002;346: 877–883.

- Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1882–1890.

- Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, etal. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter – defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl JMed 2005; 352: 225–237.

- Zabel M, Willems R, Lubinski A, Bauer A, Brugada J, Conen D, etal. Clinical effectiveness of primary prevention implantable cardioverter – defibrillators: results of the EU-CERT-ICD controlled multicentre cohort study. Eur Heart J 2020;41: 3437–3447.

- Schrage B, Uijl A, Benson L, Westermann D, Ståhlberg M, Stolfo D, et al. Association between use of primary – prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillators and mortality in patients with heart failure: aprospective propensity score-matched analysis from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Circulation 2019; 140:1530–1539.

- Køber L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, Haarbo J, Videbæk L, Korup E, etal. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1221–1230.

- Jukema JW, Timal RJ, Rotmans JI, Hensen LCR, Buiten MS, deBie MK, et al. Prophylacticuse of implantable cardioverter – defibrillators in the prevention of sudden cardiac death in dialysis patients. Circulation 2019;139: 2628–2638. 361. Sticherling C, Arendacka B, Svendsen JH, Wijers S, Friede T, Stockinger J, etal. Sex differences in outcomes of primary prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy: combined registry data from eleven European countries. Europace 2018;20: 963–970.

- Junttila MJ, Pelli A, Kenttä TV, Friede T, Willems R, Bergau L, etal. Appropriate shocks and mortality in patients with versus without diabetes with prophylactic implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Diabetes Care 2020;43: 196–200.

- Koller MT, Schaer B, Wolbers M, Sticherling C, Bucher HC, Osswald S. Death with out prior appropriate implantable cardioverter – defibrillator therapy: acompeting risks tudy. Circulation 2008;117: 1918–1926.

- ClelandJ GF, Halliday BP, Prasad SK. Selecting patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy for ICDs: myocardial function, fibrosis, and what’s attached? J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70: 1228–1231.

- Younis A, Goldberger JJ, Kutyifa V, Zareba W, Polonsky B, Klein H, etal. Predicted benefit of an implantable cardioverter- defibrillator: the MADIT-ICD benefit score. Eur Heart J2021;42: 1676–1684.

- Knops RE, OldeNordkamp LRA, Delnoy P-PHM, Boersma LVA, Kuschyk J, El-Chami MF, etal. Subcutaneous or transvenous defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 526–536. 367.ClelandJGF, DaubertJ-C, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D,KappenbergerL, etal. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med2005; 352:1539–1549.

- Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2140–2150.

- Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Klein H, Brown MW, Daubert JP, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 1329–1338.

- Masri A, Altibi AM, Erqou S, Zmaili MA, Saleh A, Al-Adham R, etal. Wearable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy for the prevention of sudden cardiac death: as ystematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5: 152–161.

- Garcia R, Combes N, Defaye P, Narayanan K, Guedon-Moreau L, Boveda S, etal. Wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with a transient risk of sudden cardiac death: the WEARIT-France cohort study. Europace 2021; 23:73–81.

- Olgin JE, Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Wranicz J, Malik R, Morin DP, etal. Wearable cardioverter-defibrillator after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2018;

379: 1205–1215.

- Scott PA, Silberbauer J, McDonagh TA, Murgatroyd FD. Impact of prolonged implantable cardioverter – defibrillator arrhythmia detection times on outcomes: a meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm 2014; 11:828–835. 374. Tan VH, Wilton SB, Kuriachan V, Sumner GL, Exner DV. Impact of programming strategies aimedat reducing non essential implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapies onmortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014; 7:164–170.

- Saeed M, HannaI, Robotis D, Styperek R, Polosajian L, Khan A, etal. Programming implantable cardioverter – defibrillators in patients with primaryprevention indication to prolong time to first shock: results from the PROVIDE study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25: 52–59. 376. Wilkoff BL, Fauchier L, Stiles MK, Morillo CA, Al-Khatib SM, Almendral J, etal. 2015 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on optimal implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming and testing. Europace 2016;18: 159–183.

- Stiles MK, Fauchier L, Morillo CA, Wilkoff BL, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS focused update to 2015 expert consensus statement on optimal implantable cardioverter – defibrillator programming and testing. Europace 2019;21: 1442–1443.

- Barsheshet A, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Jons C, Glikson M, Klein HU, etal. Long-term implications of cumulative right ventricular pacing among patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm2 011;8: 212–218.

- Wilkoff BL, Cook JR, Epstein AE, Greene HL, Hallstrom AP, Hsia H, et al. Dual-chamber pacing or ventricular back up pacing in patients with an implantable defibrillator: the Dual Chamber and VVI Implantable Defibrillator (DAVID) Trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 3115–3123.

- Olshansky B, Day JD, Moore S, Gering L, Rosenbaum M, McGuireM, etal. Is dual chamber programming inferior to single-chamber programming in an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator? Results of the INTRINSIC RV (Inhibition of Unnecessary RV Pacing With AVSH in ICDs) study. Circulation 2007;115: 9–16.

- Hindricks G, Küh lM, Dagres N. The implantable cardioverter defibrillator, conclusions on sudden cardiac death, and future perspective. ESC Cardio Med. 3rded. Oxford University Press; 2022, p2370–2376.

- Gasparini M, Proclemer A, Klersy C, Kloppe A, Ferrer JBM, Hersi A, etal. Effect of long-detection interval vs standard – detection interval for implantable cardioverter defibrillators on antitachycardia pacing and shock delivery: the ADVANCE III randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309: 1903–1911.

- Moss AJ, Schuger C, Beck CA, Brown MW, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, et al. Reduction in inappropriate therapy and mortality through ICD programming. N Engl J Med 2012;367: 2275–2283.

- Wilkoff BL, Ousdigian KT, Sterns LD, Wang ZJ, Wilson RD, Morgan JM, etal. A comparison of empiric to physician-tailored programming of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the prospective randomized multicenter EMPIRIC trial. J am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48: 330–339.

- Wilkoff BL, Williamson BD, Stern RS, Moore SL, Lu F, Lee SW, etal. Strategicpro gramming of detection and therapy parameters in implantable cardioverter defibrillators reduces shocks inprimary prevention patients: results fromthe PREPARE (PrimaryPreventionParameters Evaluation) study. J AmColl Cardiol 2008;52: 541–550.

- Gilliam FR, Hayes DL, Boehmer JP, Day J, Heidenreich PA, Seth M, etal. Real world evaluation of dual-zone ICD and CRT-D programming compared to single-zone programming: the ALTITUDEREDUCES study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2011; 22:1023–1029.

- Hernandez-Ojeda J, Arbelo E, Borras R, Berne P, Tolosana JM, Gomez-Juanatey A, etal. Patients with Brugada syndrome and implanted cardioverter-defibrillators: long-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70: 1991–2002.

- Gold MR, Weiss R, Theuns DAMJ, Smith W, Leon A, Knight BP, etal. Use of adis crimination algorithm to reduce inappropriate shocks with a subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2014;11: 1352–1358.

- Mesquita J, Cavaco D, Ferreira A, Lopes N, Santos PG, Carvalho MS, et al. Effectiveness of subcutaneous implantable cardioverter – defibrillators and determinants of inappropriate shock delivery. Int J Cardiol 2017;232: 176–180. 390. Gold MR, Lambiase PD, El-Chami MF, Knops RE, Aasbo JD, Bongiorni MG, etal. Primary results from the understanding outcomes with the S-ICD in primary prevention patients with lowe jection fraction (UNTOUCHED) trial. Circulation 2021; 143:7–17.

- Wathen MS, DeGroot PJ, Sweeney MO, Stark AJ, Otterness MF, Adkisson WO, etal. Prospective randomized multicenter trial of empirical antitachycardia pacing versus shocks for spontaneous rapid ventricular tachycardia in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: Pacing Fast Ventricular Tachycardia Reduces Shock Therapies (PainFREERxII) trial results. Circulation 2004;110: 2591–2596.

- Gulizia MM, Piraino L, Scherillo M, Puntrello C, Vasco C, Scianaro MC, etal. A randomized study to compareramp versus burst antitachycardia pacing therapies to treat fast ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: the PITAGORA ICD trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2009; 2: 146–153.

- Saxon LA, Hayes DL, Gilliam FR, Heidenreich PA, Day J, Seth M, etal. Long-term outcome after ICD and CRT implantation and influence of remotedevice follow up: the ALTITUDE survival study. Circulation 2010; 122: 2359–2367.

- Varma N, Piccini JP, Snell J, Fischer A, Dala lN, Mittal S. The relationship between level of adherence to automatic wireless remote monitoring and survival in pacemake rand defibrillator patients. J am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65: 2601–2610.

- Guédon-Moreau L, Kouakam C, Klug D, Marquié C, Brigadeau F, Boulé S, etal. Decreaseddelivery of inappropriate shocks achieved by remote monitoring of ICD: a substudy of the ECOST trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25: 763–770.

- Varma N, Michalski J, Epstein AE, Schweikert R. Automatic remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter – defibrillator lead and generator performance: the Lumos-T Safely Red Uce SRouTine Of ficeDevice Follow-Up (TRUST) trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010;3: 428–436.

- Ploux S, Swerdlow CD, Strik M, Welte N, Klotz N, Ritter P, etal. Toward seradication of inappropriate therapies for ICD lead failure by combining comprehensive remote monitoring and lead noise alerts. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2018;29: 1125–1134.

- Ellenbogen KA, Gunderson BD, Stromberg KD, Swerdlow CD. Performance of Lead Integrity Alert to assist in the clinical diagnosis of implantable cardioverter defibrillator lead failures: analysis of different implantable cardioverter defibrillator leads. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6: 1169–1177.

- Swerdlow CD, Gunderson BD, Ousdigian KT, Abeyratne A, Sachanandani H, Ellenbogen KA. Downloadable software algorithm reduces inappropriate shocks caused by implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead fractures: aprospective study. Circulation 2010;122: 1449–1455.

- Ruwald MH, Abu-Zeitone A, Jons C, Ruwald A-C, McNitt S, Kutyifa V, etal. Impact of carvedilol and metoprolol on inappropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy: the MADIT-CRT trial (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:1343–1350.

- Miyazaki S, Taniguchi H, Kusa S, Komatsu Y, Ichihara N, Takagi T, etal. Catheter ablation of atrial tachyarrhythmias causing inappropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks. Europace 2015; 17:289–294.

- Mainigi SK, Almuti K, Figueredo VM, Guttenplan NA, Aouthmany A, Smukler J, etal. Usefulness of radiofrequency ablation of supraventricular tachycardia to decrease inappropriate shocks from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. AmJ Cardiol 2012;109: 231–237.

- Kosiuk J, Nedios S, Darma A, Rolf S, Richter S, Arya A, etal. Impact of single atrial fibrillation catheter ablation on implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapies in patients with ischaemic and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. Europace 2014;16: 1322–1326.

- Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan A, etal. Early rhythm control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. NEngl J Med 2020;383: 1305–1316.

- Gasparini M, Kloppe A, Lunati M, Anselme F, Landolina M, Martinez-Ferrer JB, etal. Atrioventricular junction ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy: positive impact on ventricular arrhythmias, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies and hospitalizations: atrioventricular junction ablation in CRT patients with AF. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 1472–1481.

- Gasparini M, Galimberti P. Ratecontro l: ablation and device therapy (ablateand pace). ESC Cardio Med. 3rded. Oxford University Press; 2022, p2159–2162.

- Kitamura T, Fukamizu S, Kawamura I, Hojo R, Aoyama Y, Komiyama K, et al. Long-term efficacy of catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome and an implantable cardioverter – defibrillator to prevent inappropriate shock therapy. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13:1455–1459.

- Magyar-Russe llG, Thombs BD, Cai JX, Baveja T, Kuhl EA, Singh PP, etal. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in adults with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a systematic review. JP sychosom Res2011;71: 223–231.

- Tzeis S, Kolb C, Baumert J, Reents T, Zrenner B, Deisenhofer I, etal. Effect of depression on mortality in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients — findings from the prospective LICADstudy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011;34: 991–997.

- Andersen CM, Theuns DAMJ, Johansen JB, Pedersen SS. Anxiety, depression, ventricular arrhythmias and mortality in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: 7years’ follow-up of the MIDAS cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020; 66: 154–160.

- Berg SK, Thygesen LC, Svendsen JH, Christensen AV, Zwisler A- D. Anxietypre dicts mortality in ICD patients: results from the cross-sectional national Copen Heart ICD survey with register follow-up. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014; 37:1641–1650.

- Thylén I, Moser DK, Strömberg A, Dekker RA, Chung ML. Concerns about implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks mediate the relationship between actual shocks and psychological distress. Europace 2016; 18:828–835.

- Pedersen SS, van Domburg RT, Theuns DAMJ, Jordaens L, Erdman RAM. Concerns about the implantable cardioverter defibrillator: a determinant of anxiety and depressive symptoms independent of experienced shocks. AmHeart J 2005;149: 664–669.

- Frizelle DJ, Lewin B, Kaye G, Moniz-Cook ED. Development of a measure of the concerns held by people with implanted cardioverter defibrillators: the ICD C. Br J Health Psychol 2006;11: 293–301.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67: 361–370.

- Frydensberg VS, Johansen JB, Möller S, Riahi S, Wehberg S, Haarbo J, etal. Anxiety and depression symptoms in Danish patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: prevalence and association with indication and sex up to2 years of follow-up (data from the national DEFIB-WOMEN study). Europace 2020;22: 1830–1840.

- Hoogwegt MT, Kupper N, Theuns DAMJ, Zijlstra WP, Jordaens L, Pedersen SS. Under treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: impact on health status. Health Psychol 2012;31: 745–753.

- Lane DA, Aguinaga L, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Dan G-A,Hills MT, etal. Cardiac tachyarrhythmias and patient values and preferences for their management: the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulación Cardíaca y Electrofisiología (SOLEACE). Europace 2015; 17: 1747–1769.

- Dunbar SB, Dougherty CM, Sears SF, Carroll DL, Goldstein NE, Mark DB, etal. Educational andpsychological interventions to improve outcomes for recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and their families: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;126: 2146–2172.

- Sears SF, SowellL DV, Kuhl EA, Kovacs AH, Serber ER, Handberg E, etal. The ICD shock and stress management program: a randomized trial of psychosocial treatment tooptimizequalityof life in ICDpatients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007; 30:858–864.

- Berg SK, Rasmussen TB, Herning M, Svendsen JH, Christensen AV, Thygesen LC. Cognitive behavioural therapy significantly reduces anxiety inpatientswith implanted cardioverter defibrillator compared with usual care: findings fromthe Screen-ICD randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;27: 258–268.

- Schulz SM, Ritter O, Zniva R, Nordbeck P, Wacker C, Jack M, etal. Efficacy of a web-based intervention for improving psychosocial well- being in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: the randomized controlled ICD- FORUM trial. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 1203–1211.

- Vanden Broek KC, Tekle FB, Habibović M, Alings M, vanderVoort PH, Denollet J. Emotional distress, positive affect, and mortality in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Int J Cardiol 2013; 165: 327–332.

- Hauptman PJ, Chibnall JT, Guild C, Armbrecht ES. Patient perceptions, physician communication, and the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:571–577.

- Cikes M, Jakus N, Claggett B, Brugts JJ, Timmermans P, Pouleur A-C, etal. Cardiac implantable electronic devices with a defibrillator component and all-cause mortality in left ventricular assist device carriers: results from the PCHF-VAD registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 1129–1141.

- Galand V, Flécher E, Auffret V, Boulé S, Vincentelli A, Dambrin C, etal. Predictors and clinical impact of late ventricular arrhythmias in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018; 4: 1166–1175.

- Nakahara S, Chien C, Gelow J, Dalouk K, Henrikson CA, Mudd J, etal. Ventricular arrhythmias after left ventricular assist device. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013; 6: 648–654. 428. Clerkin KJ, Topkara VK, Demmer RT, Dizon JM, Yuzefpolskaya M, Fried J A, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device: a nanalysis of the INTERMACS registry. JACC Heart Fail 2017; 5: 916–926. 429. Oz MC, Rose EA, Slater J, Kuiper JJ, Catanese KA, Levin HR. Malignant ventricular arrhythmias are well tolerated in patients receiving long-term left ventricular assist devices. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24: 1688–1691. 430. Potapov EV, Antonides C, Crespo-Leiro MG, Combes A, Färber G, Hannan MM, etal. 2019 EACTS Expert Consensus on long-term mechanical circulatory support. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 56:230–270.

- Makki N, Mesubi O, Steyers C, Olshansky B, Abraham WT. Meta-analysis of the relation of ventricular arrhythmias to all-cause mortality after implantation of a left ventricular assist device. Am J Cardiol 2015;1 16:1385–1390.

- Yoruk A, Sherazi S, Massey HT, Kutyifa V, McNitt S, Hallinan W, etal. Predictors and clinical relevance of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ambulatory patients with a continuous flow left ventricular assist device. Heart Rhythm 2016;13: 1052–1056.

- Bedi M, Kormos R, Winowich S, McNamara DM, Mathier MA, Murali S. Ventricular arrhythmias during left ventricular assistdevicesupport. AmJ Cardiol 2007; 99: 1151–1153.

- Brenyo A, Rao M, Koneru S, Hallinan W, Shah S, Massey HT, etal. Risk of mortality for ventricular arrhythmia in ambulatory LVAD patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012; 23: 515–520.

- Vakil K, Kazmirczak F, Sathnur N, Adabag S, Cantillon DJ, Kiehl EL, etal. Implantable cardioverter – defibrillator use in patients with left ventricular assist devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2016; 4: 772–779.

- Refaat MM, Tanaka T, Kormos RL, McNamara D, Teuteberg J, Winowich S, etal. Survivalbenefit of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in left ventricular assist device-supported heart failure patients. J Card Fail 2012;18: 140–145.

- Cantillon DJ, Tarakji KG, Kumbhani DJ, Smedira NG, Starling RC, Wilkoff BL. Improved survival among ventricular assist device recipients with a concomitant implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2010;7: 466–471.

- Joyce E, Starling RC. HFrEF other treatment: ventricular assist devices. ESC Cardio Med. 3rded. Oxford University Press; 2022, p1884–1889. 439. Younes A, Al-Kindi SG, Alajaji W, Mackall JA, Oliveira GH. Presence of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and wait- list mortality of patients supported with left ventricular assist devices asbridge toheart transplantation. Int J Cardiol 2017; 231:211–215.

- Agrawa lS, Garg L, Nanda S, Sharma A, Bhatia N, Manda Y, etal. The role of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with continuous flow left ventricular assist devices–ameta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2016; 222: 379–384.

- Blomström-Lundqvist C, Traykov V, Erba PA, Burri H, Nielsen JC, Bongiorni MG, etal. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus docu menton how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID)incol laborationwiththeEuropeanAssociationforCardio-ThoracicSurgery(EACTS). Europace2020;22: 515–549.

- Burri H, Starck C, Auricchio A, Biffi M, Burri M, D’Avila A, etal. EHRA expertcon sensus statement and practical guide on optimal implantation technique for conventional pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: endorsedby the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin-AmericanHeart RhythmSociety (LAHRS). Europace 2021;23: 983–1008.

- Tarakji KG, Mittal S, Kennergren C, Corey R, Poole JE, Schloss E, etal. Antibacterial envelope to prevent cardiac implantable device infection. N Engl J Med 2019;380: 1895–1905. 444. Atti V, Turagam MK, Garg J, Koerber S, Angirekula A, Gopinathannair R, et al. Subclavian and axillary vein access versus cephalicvein cutdown or cardiac implantable electronic device implantation: ameta-analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2020;6: 661–671.

- BenzAP, Vamos M, Erath JW, Hohnloser SH. Cephalicvs. Subclavian lead implantation in cardiac implantable electronic devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace2019;21: 121–129.

446.ChanN-Y, Kwong N-P, Cheong A-P. Venous access and long-term pacemaker lead failure: comparing contrast-guided axillary vein puncture with subclavian puncture and cephalic cutdown. Europace 2017;19: 1193–1197.

- Defaye P, Boveda S, Klug D, Beganton F, Piot O, Narayanan K, etal. Dual-vs. single chamber defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death: long-term follow-up of the Défibrillateur Automatique Implantable-Prévention Primaire registry. Europace2017;19: 1478–1484.

- Dewland TA, Pellegrini CN, Wang Y, Marcus GM, Keung E, Varosy PD. Dual-chamber implantable cardioverter – defibrillators electionisassociated within creased complication rates and mortality among patients enrolled in the NCDR implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58: 1007–1013.

- Friedman PA, Bradley D, Koestler C, Slusser J, Hodge D, Bailey K, etal. Aprospective randomized trial of single- or dual-chamber implantable cardioverter defibrillators to minimize inappropriate shock risk in primary sudden cardiac death prevention. Europace 2014;16: 1460–1468.

450.Chen B-W, Liu Q, Wang X, Dang A-M. Are dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators really better than single-chamber ones? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2014;39: 273–280.

- Epstein LM, Love CJ, Wilkoff BL, Chung MK, Hackler JW, Bongiorni MG, etal. Superiorvenacava defibrillator coils make transvenous lead extraction more challenging and riskier. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61: 987–989.

- Larsen JM, Hjortshøj SP, Nielsen JC, Johansen JB, Petersen HH, Haarbo J, etal. Single-coil and dual-coil defibrillator leads and association with clinical outcomes in a complete Danish nation wide ICD cohort. Heart Rhythm 2016;13: 706–712.

- Kumar KR, Mandleywala SN, Madias C, Weinstock J, Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, etal. Singlecoil implantable cardioverter defibrillator leads in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2020;125: 1896–1900.

- Friedman PA, Rasmussen MJ, Grice S, rusty J, Glikson M, Stanton MS. Defibrillation thresholds are increased by right-sided implantation of totally transvenous implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1999;22: 1186–1192.

- Stoevelaar R, Brinkman- Stoppelenburg A, Bhagwandien RE, vanBruchem-Visser RL, Theuns DA, vanderHeide A, etal. The incidence and impact of implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks in the last phaseof life: an integratedreview. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2018;17: 477–485.

- Kapa S, Mueller PS, Hayes DL, Asirvatham SJ. Perspectives on withdrawing pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies at end of life: results of a survey of medical and legal professionals and patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:981–990.

- Padeletti L, Arnar DO, Boncinelli L, Brachman J, Camm JA, Daubert JC, etal. EHRA Expert Consensus Statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Europace2010;12: 1480–1489.

- Stoevelaar R, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, vanDriel AG, Theuns DA, Bhagwandien RE, van Bruchem-Visser RL, etal. Trends in time in the management of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator in the last phase of life: are trospective study of medical records. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019; 18: 449–457.

- Kirkpatrick JN, Gottlieb M, Sehgal P, Patel R, Verdino RJ. Deactivation of implantable cardioverter defibrillators interminal illness and end of life care. Am J Cardiol 2012; 109: 91–94.

- Stevenson WG, Khan H, Sager P, Saxon LA, Middlekauff HR, Natterson PD, etal. Identification of reentry circuit sites during catheter mapping and radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardia late aftermyocardial infarction. Circulation 1993; 88: 1647–1670.

- De Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, Tasseron S, Vermeulen JT, deJonge N, etal. Slow conduction in the infarcted human heart. “Zigzag” course of activation. Circulation 1993;88: 915–926.

- De Chillou C, Lacroix D, Klug D, Magnin-PoullI, Marquié C, Messier M, etal. Isthmus characteristics of reentrant ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002; 105: 726–731.

- Hsia HH, Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE. Characterization of endocardial electrophysiological substrate in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2003; 108:704–710.

- Soejima K, Stevenson WG, Sapp JL, Selwyn AP, Couper G, Epstein LM. Endocardial and epicardial radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardia associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. J am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43:1834–1842.

- Miljoen H, State S, Dechillou C, Magninpoull I, Dotto P, And ronache M, et al. Electroanatomic mapping characteristics of ventricular tachycardia in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Europace 2005; 7: 516–524.

- Priori SG, Blomström – Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, CammJ, etal. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricularar rhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The task force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for EuropeanPaediatric andCongenital Cardiology (AEPC). EurHeart J 2015;36: 2793–2867.

- Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, etal. 2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of patients with ventricularar rhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72: 1677–1749.

- Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, Ackerman MJ, Calkins H, Darrieux FCC, etal. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: executive summary. Heart Rhythm 2019;16: e373–e407.

- Moss AJ, Greenberg H, Case RB, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Brown MW, etal. Long-term clinical course of patients after termination of ventricular tachyarrhythmia by an implanted defibrillator. Circulation 2004; 110:3 760–3765.

- Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, RaittMH, et al. Prognostic importanceof defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2008;359: 1009–1017.

- Sapp JL, Wells GA, Parkash R, Stevenson WG, Blier L, Sarrazin J-F, etal. Ventricular tachycardia ablation versus escalation of antiarrhythmic drugs. N Engl JMed 2016; 375:111–121.

- Piccini JP, Berger JS, O’Connor CM. Amiodarone for the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J2009;30: 1245–1253.

- Palaniswamy C, Kolte D, Harikrishnan P, Khera S, Aronow WS, Mujib M, etal. Catheter ablation of post infarction ventricular tachycardia: ten – year trends in utilization, in-hospital complications, and in-hospital mortality in the United States. Heart Rhythm 2014;11: 2056–2063.

- Caceres J, Jazayeri M, McKinnie J, Avitall B, Denker ST, Tchou P, etal. Sustained bundle branch reentry as amechanismof clinical tachycardia. Circulation1989;79: 256–270.

- Blanck Z, Dhala A, Deshpande S, Sra J, Jazayeri M, Akhtar M. Bundle branch reentrant ventricular tachycardia: cumulative experience in 48 patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1993;4: 253–262.

- ChenH, Shi L, Yang B, JuW, Zhang F, Yang G, etal. Electrophysiological characteristics of bundle branch reentry ventricular tachycardia in patients without structural heart disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2018; 11: e006049.

- Pathak RK, Fahed J, Santangeli P, Hyman MC, Liang JJ, Kubala M, etal. Long-term outcome of catheter ablation for treatment of bundle branch re-entrant tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4: 331–338.

- Stevenson WG, Wilber DJ, Natale A, Jackman WM, Marchlinski FE, Talbert T, etal. Irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation guided by electroanatomic mapping for recurrent ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction: the multicenter thermocool ventricular tachycardia ablation trial. Circulation 2008;118: 2773–2782.

- DellaBella P, Baratto F, TsiachrisD, Trevisi N, Vergara P, Bisceglia C, et al. Managementof ventriculartachycardia in the setting of a dedicated unit for the treatment of complex ventricular arrhythmias: long-term outcome after ablation. Circulation 2013; 127:1359–1368.

- Maury P, Baratto F, Zeppenfeld K, Klein G, Delacretaz E, Sacher F, et al. Radio-frequency ablation as primarymanagement of well-tolerated sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia inpatientswith structural heart disease andleftventricularejectionfractionover30%. Eur Heart J 2014;35: 1479–1485.

- Tung R, Vaseghi M, Franke lDS, Vergara P, DiBiase L, Nagashima K, etal. Freedom from recurrent ventricular tachycardia after catheter ablation is associated with improved survival in patients with structural heart disease: an International VT Ablation Center Collaborative Group study. Heart Rhythm 2015;12: 1997–2007.

- Santangeli P, Zado ES, Supple GE, Haqqani HM, Garcia FC, Tschabrunn CM, etal. Long-term outcome with catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol2015;8: 1413–1421.

- Marchlinski FE, Haffajee CI, Beshai JF, Dickfeld T-ML, Gonzalez MD, Hsia HH, etal. Long-term success of irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation of sustained ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67: 674–683.

- Reddy VY, Reynolds MR, Neuzil P, Richardson AW, Taborsky M, Jongnarangsin K, etal. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl JMed2007;357: 2657–2665.

- Kuck K-H, Schaumann A, Eckardt L, Willems S, Ventura R, Delacrétaz E, et al. Catheter ablation of stable ventricular tachycardia before defibrillator implantation in patients with coronary heart disease (VTACH): a multicentrer and omised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375: 31–40.

- Anter E, Kleber AG, Rottmann M, Leshem E, Barkagan M, Tschabrunn CM, etal. Infarct-related ventricular tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4: 1033–1048. 487. Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gottlieb CD, Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2000;101: 1288–1296.

- de Chillou C, Groben L, Magnin-Poull I, Andronache M, Abbas MM, Zhang N, etal. Localizing the critical isthmus of post infarct ventricular tachycardia: the value of pace-mapping during sinus rhythm. Heart Rhythm 2014;11: 175–181.

- Jaïs P, Maury P, Khairy P, Sacher F, Nault I, Komatsu Y, etal. Elimination of localab normal ventricular activities: a new endpoint for substrate modification in patients with scar-related ventricular rtachycardia. Circulation 2012;125: 2184–2196.

- Berruezo A, Fernandez-Armenta J. Lines, circles, channels, and clouds: looking for the best design for substrate-guided ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Europace 2014;16: 943–945.

- DiBiase L, Burkhardt JD, Lakkireddy D, Carbucicchio C, Mohanty S, Mohanty P, etal. Ablation of stable VTs versus substrate ablation in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66: 2872–2882.

- Berruezo A, Fernández – Armenta J, Andreu D, Penela D, Herczku C, Evertz R, etal. Scarde channeling: new method for scar-related left ventricular tachycardia substrate ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8: 326–336.

- Haïssaguerre M, Shoda M, Jaïs P, Nogami A, Shah DC, Kautzner J, etal. Mappingand ablation of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circulation 2002;106: 962–967.

- Shirai Y, Liang JJ, Santangeli P, Arkles JS, Schaller RD, Supple GE, etal. Comparison of the ventricular tachycardia circuit between patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies: detailed characterization by entrainment. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2019;12: e007249.

- Bhaskaran A, Tung R, Stevenson WG, Kumar S. Catheter ablation of VT in nonischaemic cardiomyopathies: endocardial, epicardial and intramural approaches. Heart Lung Circ 2019; 28: 84–101.

- Tung R, Raiman M, Liao H, Zhan X, Chung FP, Nagel R, etal. Simultaneous endocardial and epicardial delineation of 3D reentrant ventricular tachycardia. J am Coll Cardiol 2020;75: 884–897.

497.Dinov B, Fiedler L, Schönbauer R, Bollmann A, Rolf S, Piorkowski C, et al. Outcomes in catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy compared with ischemic cardiomyopathy: results from the Prospective Heart Centre of Leipzig VT (HELP-VT) Study. Circulation 2014;129: 728–736.

- Proietti R, Essebag V, Beardsall J, Hache P, Pantano A, Wulffhart Z, et al. Substrate – guided ablation of haemodynamically tolerated and untolerated ventricular tachycardia in patients with structural heart disease: effect of cardiomyopathy type and acute success on long-term outcome. Europace 2015; 17:461–467.

- Ebert M, Richter S, Dinov B, Zeppenfeld K, Hindricks G. Evaluation and manage ment of ventricular tachycardia in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm2019; 16:624–631.

- Proietti R, LichelliL, Lellouche N, Dhanjal T. The challenge of optimizing ablation lesions in catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia. J Arrhythmia 2021;37: 140–147.

- Tokuda M, Sobieszczyk P, Eisenhauer AC, Kojodjojo P, Inada K, Koplan BA, etal. Transcoronary ethanol ablation for recurrent ventricular tachycardia after failed catheter ablation: an update. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4: 889–896.

- Kreidieh B, Rodríguez-Mañero M, Schurmann P, Ibarra – Cortez SH, Dave AS, Valderrábano M. Retrograde coronary venous ethanol infusion for ablation of refractory ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016;9: e004352.

- Nguyen DT, Tzou WS, Sandhu A, Gianni C, Anter E, Tung R, etal. Prospective multicenter experience with cooled radiofrequency ablation using high impedance irrigant to target deep myocardial substrate refractory to standard ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4: 1176–1185.

- Stevenson WG, Tedrow UB, Reddy V, Abdel Wahab A, Dukkipati S, John RM, etal. Infusion needle radiofrequency ablation for treatment of refractory ventricularar rhythmias. J am Coll Cardiol 2019;73: 1413–1425.