Từ khuyến cáo về điều trị nhịp nhanh trên thất ở người lớn năm 2003, năm 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS đưa ra khuyến cáo mới với nhiều khái niệm và phác đồ điều trị mới dựa trên các bằng chứng. Chúng tôi xin tóm tắt những điểm quan trọng nhất của khuyến cáo mới này.

TS Phạm Hữu Văn

Từ khóa:

• Báo cáo khoa học AHA

• Nhịp nhanh, nhịp trên thất

• Nhịp nhanh, vào lại nút nhĩ thất

• Hội chứng WPW

• Triệt phá qua catheter

• Nhịp tim nhanh, nhĩ ngoại vị

• Nhịp tim nhanh, bộ nối ngoại vị

• Cuồng nhĩ

• Thuốc chống loạn nhịp tim

• Bó nhĩ thất phụ

• Thủ thuật Valsalva

• Nhịp tim nhanh, lập lại

• Sock điện

• Khuyết tật tim, bẩm sinh

• Tử vong, đột ngột

• Kỹ thuật điện sinh lý, tim

• Nhịp xoang nhanh

Lời nói đầu

Từ năm 1980, Trường Môn Tim mạch học Hoa Kỳ (ACC) và Hội Tim mạch Mỹ (AHA) đã chuyển các chứng cứ khoa học vào các hướng dẫn thực hành với các khuyến cáo để cải thiện sức khỏe tim mạch. Các hướng dẫn này, dựa trên phương pháp có hệ thống để đánh giá và phân loại bằng chứng, cung cấp một nền tảng chăm sóc tim mạch có chất lượng.

Để đáp ứng với các báo cáo của Viện Y học [1,2] và nhiệm vụ để đánh giá hiểu biết mới và duy trì mối liên quan khi chăm sóc, nhóm công tác (Task Force) của ACC / AHA về các Hướng dẫn thực hành lâm sàng sửa đổi phương pháp luận của mình. [3,5] Các mối quan hệ giữa các hướng dẫn, tiêu chuẩn dữ liệu, tiêu chuẩn sử dụng hợp lý và các biện pháp thực hiện được đề cập ở những nơi khác. [4]

Mục đích sử dụng

Các hướng dẫn thực hành cung cấp các khuyến cáo khả năng áp dụng cho các bệnh nhân có bệnh tim mạch hoặc nguy cơ phát triển bệnh tim mạch. Trọng tâm về thực hành y tế ở Hoa Kỳ, nhưng các hướng dẫn phát triển hợp tác với các tổ chức khác có thể có một mục tiêu rộng lớn hơn. Mặc dù hướng dẫn có thể thông báo cho các quyết định điều chỉnh hoặc chi phí, chúng được chú tâm đến nâng cao chất lượng chăm sóc vì lợi ích của các bệnh nhân.

Xem xét lại bằng chứng

Các thành viên Ban Soạn thảo Hướng dẫn (Guideline Writing Committee: GWC) xem xét các tài liệu; cân nhác giá trị bằng chứng cho hay chống lại các xét nghiệm đặc biệt, phương pháp điều trị, hoặc các thủ thuật; dự toán các kết quả sức khỏe được dự kiến. Trong việc phát triển các khuyến cáo, GWC sử dụng các phương pháp trên cơ sở bằng chứng dựa trên tất cả các tư liệu có thể.[4-6] Các tài liệu tìm kiếm tập trung vào các nghiên cứu ngẫu nhiên đối chứng (randomized controlled trials: RCT) còn bao gồm cả các nghiên cứu đăng ký, so sánh không ngẫu nhiên và mô tả, hàng loạt các trường hợp, nghiên cứu thuần tập, đánh giá có hệ thống và ý kiến chuyên gia. Tài liệu tham khảo chỉ chọn được trích dẫn.

Nhóm công tác xác nhận nhu cầu khách quan, Ủy ban xem xét bằng chứng độc lập (Evidence Review Committees: ERCs) gồm các nhà phương pháp học, dịch tế học, lâm sàng và thông kê sinh học đã khảo sát có hệ thống, tóm tắt và đánh giá bằng chứng để giải quyết các câu hỏi lâm sàng mấu chốt được đặt ra trong định dạng PICOTS (P = dân số , I = can thiệp, C = so sánh, O = kết quả, T = thời gian, S = tình huống).(P=population, I=intervention, C=comparator, O=outcome, T= timing, S= setting)[4,5] Cân nhắc thực tế, bao gồm cả thời gian và nguồn lực, giới hạn ERCs đối với bằng chứng có liên quan đến các câu hỏi lâm sàng mấu chốt và tự nỗ lực xem xét và phân tích hệ thống có thể ảnh hưởng đến sức mạnh của các khuyến cáo tương ứng. Các khuyến cáo được GWC phát triển trên cơ sở các xem xét các bằng chứng hệ thống.

Điều trị Nội khoa được Hướng dẫn Trực tiếp

Thuật ngữ “Điều trị nội khoa được hướng dẫn trực tiếp” dùng cho chăm sóc được xác định chủ yếu do các khuyến cáo Class I của ACC / AHA. Đối với những điều này và tất cả các phác đồ điều trị bằng thuốc được khuyến cáo, người đọc cần xác nhận liều lượng các chất có trong sản phẩm và đánh giá cẩn thận các chống chỉ định và tương tác. Khuyến cáo được giới hạn điều trị, các thuốc và các thiết bị đã được chấp thuận cho sử dụng lâm sàng tại Hoa Kỳ.

Class các Khuyến cáo và Mức độ Bằng chứng

Class các Khuyến cáo (Class of Recommendation: COR) (Tức sức mạnh của khuyến cáo) gồm mức độ đã được biết và sự chắc chắn của lợi ích tương ứng với rủi ro. Cấp chứng cứ (Level of evidence: LOE) đánh giá các bằng chứng ủng hộ ảnh hưởng của can thiệp trên cơ sở các type, chất lượng, số lượng và tính nhất quán của dữ liệu từ các thử nghiệm lâm sàng và các báo cáo khác (Bảng 1) .[5,7] Trừ khi có quy định khác, các khuyến cáo được sắp xếp do COR và sau đó LOE. Trường hợp dữ liệu so sánh tồn tại, chiến lược ưa thích được ưu tiên. Khi > 1 một thuốc, chiến lược, hoặc điều trị tồn tại trong cùng một COR và LOE cũng không có dữ liệu so sánh có sẵn, tùy chọn được liệt kê theo thứ tự abc. Mỗi khuyến cáo tiếp theo là văn bản bổ sung liên quan đến ủng hộ tài liệu tham khảo và các mục bằng chứng.

Bảng 1: Áp dụng Class được khuyến cáo và Mức độ chứng cứ khuyến cáo cho chiến lược lâm sàng, can thiệp, điều trị, hoặc kiểm tra chẩn đoán trong chăm sóc bệnh nhân *

|

Class được khuyến cáo |

Mức độ bằng chứng |

|

Class I Lợi ích >>> Nguy cơ |

Mức độ A |

|

Các cụm từ được gợi ý cho soạn thảo các khuyến cáo: ■ Được khuyến cáo ■ Được chỉ định / hữu ích / hiệu quả / có lợi ■ Nên được thực hiện / sử dụng / các vấn đề khác ■ Hiệu quả được so sánh. Các cụm: ▫ Điều trị / chiến lược A được khuyến cáo / được chỉ định ưa chuộng hơn điều trị B ▫ Điều trị A nên được lựa chọn hơn điều trị B |

■ Các bằng chứng chất lượng cao từ > 1 RCT ■ Các phân tích gộp từ các RCT chất lượng cao. ■ 1 hoặc > 1 RCT được xem xét từ các nghiên cứu đăng ký chất lượng cao.

|

|

Class IIa Lợi ích >> Nguy cơ |

Mức độ B-R (R: ngẫu nhiên) |

|

Các cụm từ được gợi ý cho soạn thảo các khuyến cáo: ■ Là phù hợp ■ Có thể hữu ích / hiệu quả / có lợi ■ Hiệu quả được so sánh. Các cụm: ▫ Điều trị / chiến lược A nhiều khả năng được khuyến cáo / được chỉ định ưa chuộng hơn điều trị B ▫ Là phù hợp để lựa chọn điều trị A hơn điều trị B |

■ Các bằng chứng chất lượng trung bình từ từ 1 hoặc > 1 RCT. ■ Phân tích gộp từ các RCTs có chất lượng trung bình.

|

|

Class IIb Lợi ích ≥ Nguy cơ |

Mức độ B-NR (không ngẫu nhiên) |

|

Các cụm từ được gợi ý cho soạn thảo các khuyến cáo: ■ Có thể / có lẽ là phù hợp ■ Có thể / có lẽ được xem xét ■ Tính hữu ích / hiệu quả còn chưa được biết / chưa rõ ràng / chưa chắc chắn hoặc chưa được tính toán rõ. |

■ Các bằng chứng chất lượng trung bình từ từ 1 hoặc > 1 các nghiên cứu được thiết kế tốt hoàn thành tốt không ngẫu nhiên, các nghiên cứu quan sát hoặc đăng ký. ■ Phân tích gộp các nghiên cứu như vậy

|

|

Class III (trung bình) Lợi ích = Nguy cơ |

Mực C – LD (từ liệu hạn chế) |

|

Các cụm từ được gợi ý cho soạn thảo các khuyến cáo: ■ Không được khuyến cáo ■ Không được chỉ định / hữu ích / hiệu quả / có lợi ■ Không nên được thực hiện / sử dụng / các vấn đề khác |

■ Các nghiên cứu quan sát hoặc đăng ký ngẫu nhiên hoặc không ngẫu nhiên với sự hạn chế về thiết kế hoặc thực hiện. ■ Phân tích gộp các nghiên cứu như vậy ■ Các nghiên cứu sinh lý hoặc cơ học ở cơ thể người. |

|

Class III (mạnh) Nguy cơ > lợi ích |

Mức độ C-EO (ý kiến chuyên gia) |

|

Các cụm từ được gợi ý cho soạn thảo các khuyến cáo: ■ Nhiều khả năng có hại. ■ Gây hại. ■ Được kết hợp với tăng tử suất / bệnh suất ■ Không nên thực hiện / sử dụng / các vấn đề khác. |

Sự đồng thuận các ý kiến chuyên gia trên cơ sở kinh nghiệm lâm sàng. |

1. Giới thiệu

1.1. Phương pháp luận và bằng chứng xem xét

Các khuyến nghị được liệt kê trong hướng dẫn này là bất cứ khi nào có thể, dựa trên bằng chứng. Xem xét lại bằng chứng bao quát được thực hiện vào tháng 4 năm 2014 trong đó có tư liệu được xuất bản thông qua tháng chín năm 2014. Các tài liệu tham khảo được lựa chọn xuất bản qua tháng 5 năm 2015 đã được GWC hợp nhất. Tư liệu bao gồm bắt nguồn từ nghiên cứu liên quan đến đối tượng con người, được xuất bản bằng tiếng Anh và lập chỉ mục trong MEDLINE (thông qua PubMed), EMBASE, Thư viện Cochrane, Cơ quan cho Nghiên cứu chăm sóc Sức khỏe và chất lượng, và cơ sở dữ liệu được lựa chọn khác có liên quan đến hướng dẫn này. Các thuật ngữ tìm kiếm có liên quan và các dữ liệu gồm có trong các bảng bằng chứng bổ sung tư liệu trực tuyến. Ngoài ra, các GWC xem xét lại các tài liệu liên quan đến nhịp nhanh trên thất (SVT) công bố trước đây của ACC, AHA và HRS. Tài liệu tham khảo được lựa chọn và công bố trong tài liệu này đại diện và không bao gồm tất cả.

Một ERC độc lập đã được giao nhiệm vụ thực hiện một hệ thống các câu hỏi lâm sàng quan trọng, kết quả trong số đó đã được GWC xem xét hợp nhất đưa vào hướng dẫn này. Báo cáo đánh giá có hệ thống về điều chỉnh bệnh nhân với hội chứng Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) không triệu chứng đã được xuất bản kết hợp với hướng dẫn này. [10]

1.2. Tổ chức của GWC

GWC bao gồm các nhà lâm sàng, tim mạch học, điện sinh lý học (gồm cả các chuyên gia nhi khoa) và điều dưỡng (trong vai trò đại diện bệnh nhân) và các đại diện từ ACC, AHA và HRS.

1.3. Xem xét lại tư liệu và chấp thuận

Tư liệu này đã được các nhà phê bình chính thức được ACC, AHA và HRS, và cả các nhà phê bình tự nguyện riêng biệt. Các thông tin RWI của các nhà phê bình được bổ xung cho GWC và được xuất bản trong tư liệu này.

Tư liệu này đã được chấp thuận cho xuất bản do các hội đồng điều hành của ACC, AHA và HRS.

1.4. Quy mô của hướng dẫn

Mục đích tư liệu của ACC/AHA/HRS chung này cung cấp hướng dẫn hiện thời cho việc điều chỉnh ở người lớn với tất cả các loại SVT ngoại trừ rung nhĩ (AF). Mặc dù, nói một cách khắt khe, SVT, nhưng thuật ngữ SVT nói chung không ám chỉ AF.. AF đã được viết trong hướng dẫn của ACC/AHA/HRS năm 2014 cho điều chỉnh rung nhĩ (chúng tôi đã dăng tóm tắt trong số tháng 5 năm 2014). [11] Hướng dẫn hiện tại trình bày các SVT khác, gồm nhịp nhanh QRS hẹp, cũng như các nhịp nhanh khác, SVT không đều, (chẳng hạn nhĩ với đáp ứng thất không đều và nhịp nhanh nhĩ đa hổ [MAT]).

Hướng dẫn này thay thé hướng dẫn “Năm 2003 của ACC/AHA/ESC cho điều chỉnh các bệnh nhân loạn nhịp nhanh trên thất.”[12] Mặc dù tư liệu này tập chung vào quần thể người lớn (≥18 tuối) và đưa ra không phải các khuyến cáo chuyên biệt cho bệnh nhân nhi, như liệt kê tài liệu tham khảo, chúng tôi đã khảo cứu tư liệu gồm các các bệnh nhân nhi. Trong một số trường hợp, tư liệu tử các bệnh nhân nhi không phải sơ sinh đã giúp cung cấp thông tin cho khuyến cáo này.

2.Các nguyên tắc chung

2.1. Các cơ chế và định nghĩa

Cho các mục đích của khuyến cáo này,SVT được định nghĩa như Bảng 2, cung cấp các định nghĩa và các cơ chế của mỗi type của SVT. Thuật ngữ SVT nói chung không bao gồm AF, tư liệu này không thảo luận điều chỉnh AF.

Bảng 2. Các thuật ngữ thích hợp và định nghĩa

|

Rối loạn nhịp / Thuật ngữ |

Định nghĩa |

|---|---|

|

Nhịp nhanh trên thất (SVT) |

Một thuật ngữ chung dùng để mô tả nhịp tim nhanh (tần số nhĩ và / hoặc thất vượt quá 100 bpm lúc nghỉ), các cơ chế trong đó bao gồm liên quán đến tổ chức từ bó His hoặc trên. Các SVTs này gồm nhịp xoang nhanh không phù hợp, AT (bao gồm cả AT một ổ hoặc đa ổ), AT vòng vào lại lớn (gồm cuống nhĩ (AFL) điển hình), nhịp tim nhanh bộ nối, AVNRT, và các hình thức khác của nhịp tim nhanh vào lại qua trung gian các đường phụ. Trong hướng dẫn này, thuật ngữ này không bao gồm AF. |

|

Nhịp nhanh kịch phát trên thất (PSVT) |

Một hội chứng lâm sàng được đặc trưng bằng sự hiện diện của nhịp nhanh và đều khởi phát và chấm dứt đột ngột. Những đặc tính này đặc trưng cho AVNRT hoặc AVRT và ít hơn, AT. PSVT đại diện cho một nhóm nhỏ SVT. |

|

Rung nhĩ (AF) |

Một rối loạn nhịp trên thất với hoạt động nhĩ không được phối hợp và do đó, sự co tâm nhĩ không hiệu quả,.các đặc tính ECG gồm: 1) hoạt động nhĩ không đều, 2) không có sóng P khác biệt và 3) khoảng R-R không đều (khi dẫn truyền nhĩ thất hiện hữu). AF không được đề cập trong tài liệu này. |

|

Nhịp xoang nhanh |

Nhịp phát sinh từ nút xoang, trong đó tần số xung vượt quá 100 bpm. |

|

• Nhịp xoang nhanh sinh lý |

Tần số xoang được tăng lên phù hợp đáp ứng lại với gắng sức và cả các tình huống khác làm tăng trương lực giao cảm. |

|

• Nhịp xoang nhanh không phù hợp |

Tần số xoang của tim > 100 bpm lúc nghỉ, với tần số tim trung bình 24 h > 90 bpm không phải do phản ứng sinh lý phù hợp hoặc các nguyên nhân tiên phát như cường giáp hoặc thiếu máu. |

|

Nhịp nhanh nhĩ (AT) |

|

|

• AT ổ |

Một SVT phát sinh từ vị trí khu trú ở nhĩ, được đặc trưng bằng hoạt động của nhĩ đều, có tổ chức với các sòng P tách biệt và đoạn đẳng điện điển hình giữa các sóng P. Đôi khi, nhận thấy sự không đều, đặc biệt là lúc khởi đầu (“hâm nòng”) và kết thúc (“làm nguội”). Lập bản đồ nhĩ phát hiện điểm nguồn gốc ổ. |

|

• Nhịp nhanh vào lại tại nút xoang (Sinus node reentry tachycardia) |

Một loại hình đặc biệt của AT ổ do vòng vào lại micro phát sinh từ phúc hợp nút xoang, đặc trưng bằng khởi phát và châm dứt đột ngột, kết quả hình thái sóng P không thể phân biệt sóng P nhịp xoang. |

|

• Nhịp nhanh nhĩ đa ổ (Multifocal atrial tachycardia: MAT) |

SVT không đều được đặc trưng bằng SVT ≥3 sóng P có hình thái khác biệt và hoặc các mẫu của hoạt động nhĩ ở tần số khác biệt. Nhịp thường không đều.. |

|

Cuồng nhĩ |

|

|

• Cuồng nhĩ phụ thuốc eo tĩnh mạch chủ và van 3 lá: type đỉnh hình (Cavotri-cuspid isthmusdependent atrial flutter: typical) |

AFL vòng vào lại lớn lan truyền quang vòng 3 lá, đi trước phía trên dọc vách nhĩ, phía dưới dọc thành nhĩ phải, qua eo tĩnh mạch chủ và van 3 lá giữa vòng van 3 lá và van Eustach và chỏm. Chuỗi hoạt động này tạo ra các sóng cuồng nhĩ “răng cưa” âm chiếm ưu thế trên ECG ở chuyển đạo 2,3 và aVF và đổi hướng dương trễ ở V1. Tần số nhĩ có thể chậm điển hình < 300 bpm (chiều dài chu kỳ 200 ms) khi có thuốc chống loạn nhịp hoặc xơ sẹo. Nó cũng được biết như “cuồng nhĩ điển hình”, hoặc “cuồng nhĩ phụ thuộc eo tĩnh mạch chủ 3 lá” hoặc “cuồng nhĩ ngược chiều kim đồng hồ” ( “counterclockwise atrial flutter.”) |

|

• Cuồng nhĩ phụ thuốc eo tĩnh mạch chủ và van 3 lá : type đảo nghịch ( reverse typical) |

AFL vòng vào lại lớn lan truyền quanh theo hướng đảo ngược của “cuồng nhĩ điểu hình”. Các sóng cuồng nhĩ biểu hiện dương điển hình ở các chuyển đạo dưới và âm ở V1. Type này của cuồng nhĩ cũng được quy cho như cuồng nhĩ “type đảo nghịch” hoặc “cuồng nhĩ type theo chiều kim đồng hồ” “clockwise typical atrial flutter.” |

|

• Cuồng nhĩ không điển hình hoặc không phụ thuộc eo tính mạch chủ 3 lá. |

Các AFL vào lại vòng lớn không liên quan đến eo tĩnh mạch chu 3 lá. Tính đa dạng các vòng vào lại có thể bao gồm vào lại quanh vòng van 2 lá hoặc tổ chức sẹo trong phạm vị nhĩ phải hoặc trái. Tính đa dạng của các thuật ngữ đã được áp dụng cho các loạn nhịp này theo khu vực vòng vào lại, gồm các hình thái riêng biệt, như “cuồng nhĩ LA” và “nhịp nhanh vào lại vòng lớn LA” hoặc nhịp nhanh vào lại nhĩ tổn thương do cắt (incisional) do vào lại quanh các sẹo ngoại khoa. |

|

Nhịp nhanh bộ nối (Junctional tachycardia) |

SVT không do vào lại xuất hiện từ bộ nối (bao gồm cả bó His). |

|

Nhịp nhanh vào lại nút nhĩ thất. (Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia: AVNRT) |

Nhịp nhanh vào lại liên quan đến 2 đường chức năng khác biệt nhau, thường được quy cho các đường “nhanh” và “chậm”. Đại đa số, đường nhanh khu trú gần đỉnh tam giác Koch, và đường chậm sau dưới tổ chức chắc nút AV. Các đường biến thể đã được mô tả, cho phép AVNRT “chậm chậm”. |

|

• AVNRT điển hình |

AVNRT trong đó đường chậm làm đường xuôi của vòng và đường nhanh làm đường ngược (còn được gọi AVNRT chậm- nhanh) |

|

• AVNRT không điển hình |

AVNRT trong dó đường nhanh làm đường xuôi của vòng và đường chậm làm đường ngược (còn được gọi là vào lại nút AV nhanh – chậm) hoặc đường chậm là đường xuôi và đường chậm thứ hai là đường ngược (còn gọi là AVNRT chậm – chậm) |

|

Đường phụ (Accessory pathway) |

Với mục đích của hướng dẫn này, một đường phụ được định nghĩa là một đường ngoài nút AV kết nối cơ nhĩ với cơ thất qua rãnh AV tâm nhĩ đến tâm thất trên rãnh AV. Các đường phụ có thể được phân loại theo vị trí của chúng, loại dẫn truyền (giảm dần (decremental) hoặc không giảm dần (nondecremental)), và chúng có khả năng dẫn xuôi, ngược, hoặc cả hai hướng hay không. Đáng chú ý, các con đường phụ các loại khác (chẳng hạn như nhĩ bó (atriofascicular), nút bó (Nodo-fascicular), bó thất (Nodo- ventricular), thường ít và được chỉ được nói ngắn gọn trong tài liệu này (Phần 7). |

|

• Đường phụ có biểu hiện (Manifest accessory pathways) |

Đường dẫn truyền xuôi gây mẫu kích thích thất sớm trên ECG. |

|

• Đường phụ ẩn (Concealed accessory pathway) |

Đường dẫn truyền chỉ ngược và không biểu hiện trên mẫu ECG trong quá trình nhịp xoang. |

|

• Mẫu kích thích sớm (Pre-excitation pattern) |

Mẫu ECG phản ảnh sự có mặt của đường phụ có biểu hiện nối nhĩ với thất. Hoạt động thất được kích thích sớm qua đường phụ cạnh tranh với dẫn truyền xuôi qua nút AV và lan truyền tử hướng đường phụ đi vào trong cơ thất. Phụ thuộc đóng góp tương đối từ hoạt động thất do hệ nút AV/hệ thống His Purkinje đối lại với đường phụ được biểu hiện, mức độ thay đổi của kích thích sớm, với các mẫu đặc trưng của khoảng P-P ngắn với sự lúi ríu (slurring) của đường đi lên khởi đầu của phức bộ QRS (sóng delta), được nhìn thấy. Kích thích sớm có thể không liên tục hoặc không dễ dàng nhận thấy đối với một số con đường có khả năng dẫn truyền xuôi; điều này thường được kết hợp với một con đường có nguy cơ thấp, nhưng ngoại lệ xảy ra. |

|

• Kích thích sớm không triệu chứng (Asymptomatic pre-excitation) (isolated pre-excitation) |

Mẫu ECG kích thích sớm bất thường không có ở các SVT được chứng minh bằng tư liệu hoặc triệu chứng phù hợp với SVT. |

|

• Hội chứng Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW). |

Hội chứng được đặc trưng bằng SVT được chứng minh bằng tư liệu hoặc các triệu chứng phù hợp với SVT ở các bệnh nhân có kích thích thất sớm trong quá trình nhịp xoang. |

|

Nhịp nhanh vào lại nhĩ thất. (Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia: AVRT) |

Nhịp nhanh vào lại, đường điện học của nó đòi hởi có đường phụ, nhĩ, nút AV (hoặc đường thứ 2), và thất. |

|

• Orthodromic AVRT |

AVRT trong đó xung vào lại sử dụng đường phụ theo hướng ngược từ thất lên nhĩ và nút AV ở hướng xuôi. Phức hợp QRS thường hẹp hoặc có thể rộng do blốc nhánh bó có từ trước hoặc dẫn truyền lệch hướng. |

|

• Antidromic AVRT |

AVRT trong đó xung vào lại sử dụng đường phụ theo hướng xuôi từ nhĩ xuống thất và nút AV theo hướng ngược. Đôi khi, thay nút AV, có thể sử dụng đường phụ khác theo hướng ngược, được quy cho như là AVRT được kích thích sớm (pre-excited AVRT). Phức bộ QRS rộng (được kích thích sớm tối đa). |

|

Hình thái cố định của nhịp nhanh lặp lại bộ nối (Permanent form of junctional reciprocating tachycardia: PJRT) |

Hình thái hiếm của AVRT orthodromic gần như liên hồi liên quan đến dẫn truyền chậm, bị ẩn, thường đường phụ ở sau vách (slowly conducting, concealed, usually posteroseptal accessory pathway). |

|

AF được kích thích sớm |

AF với kích thích sớm thất gây ra do dẫn truyền qua ≥ 1 đường phụ. |

AF: rung nhĩ; AT: nhịp nhanh nhĩ; AFL: cuồng nhĩ; AV: nhĩ thất AVNRT: nhịp nhanh vào lại nút AV; AVRT: nhịp nhanh vào lại nhĩ thất; bpm, nhắt bóp /phút; ECG: điện tâm đồ/ghi điện tâm đồ; LA: nhĩ trái; MAT: nhịp nhanh nhĩ đa; PJRT: hình thái cố định của nhịp nhanh lặp lại bộ nối; PSVT: nhịp nhanh kịch phát trên thất; SVT: nhịp nhanh trên thất; WPW: Wolff-Parkinson-White.

2.2. Dịch tễ học, Nhân khẩu học và Tác động Sức khỏe Cộng đồng

Các bằng chứng tốt nhất cho thấy sự phổ biến của SVT trong dân số chung khoảng 2,29/1000 người. [13] Khi điều chỉnh theo độ tuổi và giới tính trong dân số Hoa Kỳ, tỷ lệ nhịp nhanh trên thất kịch phát (PSVT) ước tính khoảng 36 / 100 000 người mỗi năm [13]. Có khoảng 89 000 trường hợp mới mỗi năm và 570 000 người có PSVT [13]. So sánh với các bệnh nhân có bệnh tim mạch, những người có PSVT không cần bất kỳ bệnh tim mạch nào là trẻ hơn (37 đối lại 69 tuổi; P = 0,0002) và có PSVT nhanh hơn (186 đối lại 155 bpm; P = 0,0006). Phụ nữ có hai lần nguy cơ so với nam giới phát triển PSVT. [13]. Các cá nhân > 65 tuổi có > 5 lần nguy cơ so với người trẻ hơn phát triển PSVT. [13]

Nhịp nhanh vào lại nút nhĩ thất (AVNRT) phổ biến hơn ở những người tuổi trung niên trở lên, trong khi đó ở thanh thiếu niên tỷ lệ có thể được cân bằng hơn giữa nhịp nhanh vào lại nhĩ thất (AVRT) và AVNRT, hoặc AVRT có thể phổ biến hơn. [13] Tần số tương đối của nhịp tim nhanh qua trung gian đường phụ giảm theo tuổi. Tỷ lệ kích thích sớm biểu hiện hoặc mẫu WPW trên điện tâm đồ / các đường ghi điện tâm đồ (ECG) trong dân số chung từ 0,1% đến 0,3%. Tuy nhiên, không phải tất cả những bệnh nhân có kích thích sớm biểu hiện phát triển PSVT. [14-16]

2.3. Đánh giá các bệnh nhân SVT nghi ngờ hoặc đã được chứng minh bằng tư liệu

2.3.1. Biểu hiện lâm sàng và Chẩn đoán phân biệt trên Cơ sở các triệu chứng

Chẩn đoán SVT thường được thực hiện ở các khoa cấp cứu, nhưng thường được khám phá từ những triệu chứng gợi ý SVT trước khi có những tư liệu điện tâm đồ khởi đầu. Khởi phát triệu chứng SVT thường bắt đầu ở tuổi trưởng thành; trong một nghiên cứu ở người lớn, tuổi trung bình của khởi phát các triệu chứng là 32 ± 18 tuổi đối với AVNRT, so với 23 ± 14 tuổi đối với AVRT. [17] Ngược lại, trong một nghiên cứu được tiến hành ở các quần thể trẻ em, độ tuổi trung bình khởi phát các triệu chứng của AVRT và AVNRT là 8 và 11 tuổi, tương ứng. [18] So sánh với AVRT, bệnh nhân AVNRT có nhiều khả năng ở nữ, có độ tuổi khởi bệnh > 30 năm. [16,19-21]

SVT ảnh hưởng đến chất lượng cuộc sống, điều này thay đổi theo tần số cơn, khoảng thời gian của SVT, cho dù các triệu chứng xảy ra không chỉ với gắng sức mà còn cả lúc nghỉ [18,22]. Trong 1 nghiên cứu hồi cứu trong đó ghi nhận các bệnh nhân < 21 tuổi với mẫu WPW trên điện tâm đồ đã được xem xét lại, 64% các bệnh nhân có biểu hiện triệu chứng và thêm 20% phát triển triệu chứng trong thời gian theo dõi. [23] Phương thức biểu hiện gồm: 38% SVT được chứng minh bằng tư liệu, đánh trống ngực ở 22%, đau ngực 5%, ngất ở 4%, AF ở 0,4% và đột tử tim (SCD) ở 0,2%. [23] Một yếu tố gây nhiễu trong việc chẩn đoán SVT cần thiết phân biệt các triệu chứng của SVT từ các triệu chứng của rối loạn hoảng sợ và lo âu hay bất kỳ điều kiện nhận biết nhịp xoang nhanh được tăng thêm (như hội chứng tim nhanh tư thế đứng). Khi AVNRT và AVRT được so sánh, các triệu chứng xuất hiện có sự khác biệt đáng kể. Bệnh nhân AVNRT thường xuyên hơn mô tả triệu chứng của “áo đập” (shirt flapping) hoặc “cổ đập” (neck pounding) [19,24] có thể liên quan đến dòng dội ngược khi nhĩ phải co bóp chống lại van 3 lá đóng (cannon a waves).

Ngất thật sự ít gặp trong SVT, nhưng phổ biến than phiên về choáng váng. Ở những bệnh nhân có hội chứng WPW, ngất có thể xẩy ra trầm trọng, nhưng không nhất thiết phải liên quan với tăng nguy cơ đột tử tim (SCD). [25] Tần số AVRT thường nhanh hơn khi AVRT xẩy ra khi gắng sức, [26] nhưng tần số đơn thuần không giải thích được các triệu chứng gần ngất (say sẩm). Các bệnh nhân cao tuổi với AVNRT dễ bị ngất hoặc gần ngất hơn là bệnh nhân trẻ, nhưng tần số nhịp tim nhanh nói chung ở người già chậm hơn. [27,28]

Trong một nghiên cứu về mối quan hệ của SVT với lái xe, 57% bệnh nhân trải qua một cơn SVT trong khi lái xe, 24% trong số này coi đây là một trở ngại cho lái xe. [29] Ý kiến này phổ biến nhất ở những bệnh nhân đã trải qua ngất hoặc gần ngất. Trong số những bệnh nhân trải qua SVT trong khi lái xe, 77% cảm thấy mệt mỏi, 50% có triệu chứng gần ngất và 14% trải qua ngất. Phụ nữ có triệu chứng nhiều hơn trong mỗi loại.

2.3.2. Đánh giá ECG

Ghi nhận ECG 12 chuyển đạo trong quá trình nhịp nhanh và trong quá trình nhịp xoang có thể phát hiện căn nguyên của nhịp nhanh. Đối với các bệnh nhân mô tả các cơn trước đó, chứ không phải hiện tại, các triệu chứng hồi hộp, ECG lúc nghỉ có thể nhận biết được kích thích sớm nên gửi ngay đến các bác sỹ điện sinh lý tim.

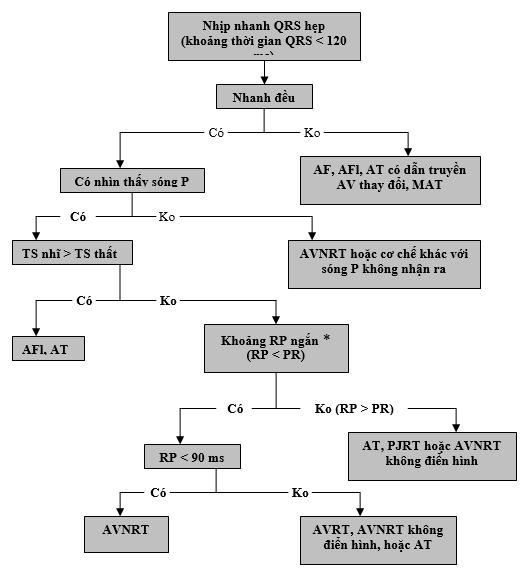

Đối với bệnh nhân biểu hiện SVT, ECG 12 chuyển đạo có thể có khả năng nhận biết cơ chế rối loạn nhịp (Hình 1). Nếu SVT đều, điều này có thể đặc trưng cho AT với dẫn truyền 1:1 hoặc SVT có liên quan đến nút nhĩ thất (AV). nhịp tim nhanh bộ nối, có nguồn gốc ở bộ nối AV (gồm cả bó His), có thể đều hoặc không đều, với dẫn truyền đến nhĩ thay đổi. SVTs liên qua đến nút AV khi cấu thành đòi hỏi vòng vào lại nhịp nhanh gồm AVNRT (Phần 6) và AVRT (Phần 7). Trong nhịp nhanh vào lại này, sóng P được dẫn truyền ngược có thể khó phát hiện, đặc biệt là nếu có blốc nhánh bó. Trong AVNRT điển hình, hoạt động nhĩ gần cùng lúc với QRS, vì vậy phần chia sóng P kết thúc thường được định vị ở chỗ kết thúc của phức bộ QRS, xuất hiện như sự lệch hẹp và âm ở các chuyển đạo dưới (một làn sóng giả S) và một chút lệch dương nhẹ ở cuối của phức bộ QRS ở chuyển đạo V1 (pseudo R ‘). Trong AVRT orthodromic (với dẫn truyền xuôi qua nút AV), các sóng P thường có thể được nhìn thấy ở phần đầu đoạn ST-T. Trong hình thức điển hình của AVNRT và AVRT, do các sóng P nằm gần sát với phức bộ QRS trước hơn QRS tiếp sau, nhịp nhanh được gọi là có “RP ngắn.” Trong trường hợp ít gặp của AVNRT (chẳng hạn như “nhanh-chậm “), các sóng P ở gần sát với phức bộ QRS tiếp theo hơn, dẫn đến RP dài. RP cũng là dài trong một hình thức phổ biến của AVRT, gọi là hình thức cố định của nhịp nhanh lặp lại bộ nối (PJRT), trong đó bó nối tắt phụ ít gặp với dẫn truyền ngược “giảm” (dẫn truyền chậm) trong quá trình AVRT orthodromic gây ra hoạt động nhĩ chậm và khoảng RP dài.

Hình 1 chỉ ra thuật toánchẩn đoán phân biệt nhịp nhanh QRS hẹp ở người lớn. Bệnh nhân có nhịp tim nhanh bộ nối có thể tương tự mẫu AVNRT chậm – nhanh và có thể cho thấy phân ly và /hoặc không đều rõ ở tần số bộ nối. * RP được cho là khoảng thời gian từ khởi đầu QRS trên ECG bề mặt đến khởi phát của sóng P có thể nhìn thấy (ghi nhận khoảng 90 ms được xác nhận trên ECG bề mặt, [30] khi ngược lại với khoảng thất nhĩ 70 ms được sử dụng cho chẩn đoán ECG trong buồng tim) [31]. AV chỉ nhĩ thất; AVNRT: nhịp nhanh vào lại nút nhĩ thất; AVRT: nhịp nhanh vào lại nhĩ thất; ECG: điện tâm đồ; MAT, nhịp nhanh nhĩ đa ổ; và PJRT: nhịp nhanh lặp lại bộ nối cố định. AF: rung nhĩ; AFl: cuồng nhĩ; AT: nhanh nhĩ.

Được thay đổi với sự cho phép từ Blomstrưm-Lundqvist et al. [12]

Khoảng thời gian RP dài biểu hiện điển hình của AT vì nhịp được phát ra do nhĩ và dẫn bình thường xuống thất. Trong AT, ECG sẽ thường xuất hiện một làn sóng P có hình thái khác với sóng P trong nhịp xoang. Trong nhịp nhanh vào lại nút xoang, dạng AT ổ, hình thái học của sóng P giống với sóng P trong nhịp xoang.

2.4. Các nguyên tắc điều trị nội

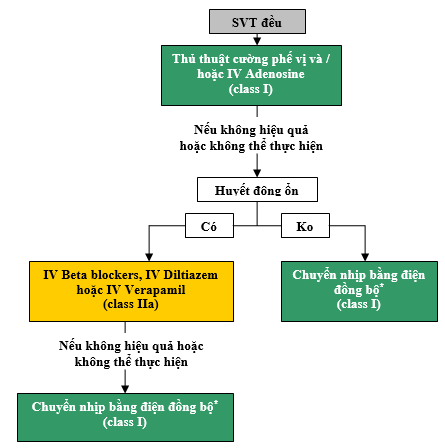

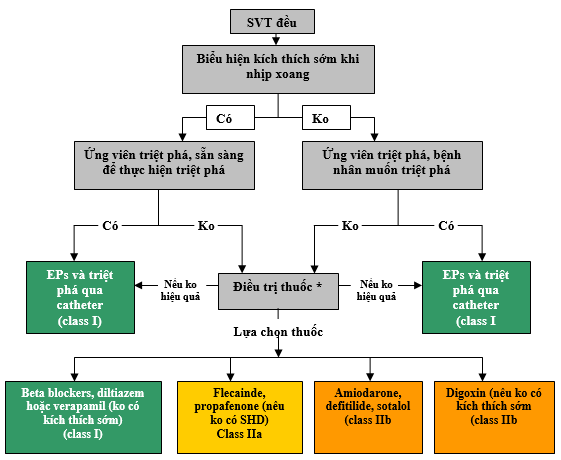

Xem Hình 2 về thuật toán để điều trị cấp cứu nhịp nhanh cơ chế chưa rõ và Hình 3 cho thuật toán điều trị liên tục nhịp nhanh có cơ chế chưa biết. Xem Phụ lục 1 trong bổ sung tư liệu trực tuyền cho bảng điều trị thuốc cấp thời SVT (tiêm tĩnh mạch), Phụ lục 2 cho bảng điều trị thuốc liên tục SVT (sử dụng uống), và bổ sung tư liệu trực tuyến 1 đến 3 cho các tư liệu ủng hộ Phần 2.

Hình 2 cho điều trị cấp thời SVT đều cơ chế chưa được biết. Màu sắc tương ứng với class Khuyến nghị trong Bảng 1; thuốc được liệt kê theo thứ tự abc. * Đối với các nhịp mất đi hoặc tái phát tự phát, chuyển nhịp đồng bộ là không thích hợp. IV: tĩnh mạch; và SVT: nhịp nhanh trên thất.

Hình 3 biểu thị thuật toán điều chỉnh tiếp tục SVT cơ chế chưa được biết. Màu sắc tương ứng với các class khuyến cáo ở bảng 1; thuốc được liệt kê theo thứ tự abc. * Lâm sàng tiếp theo không cần điều trị cũng là một lựa chọn. EPs: nghiên cứu điện sinh lý. SHD: bệnh tim thực thể, (gồm bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ); SVT: nhịp nhanh trên thất.

2.4.1. Điều trị cấp thời: Các khuyến cáo (Xem KC-1)

Do khoảng 50. 000 bệnh nhân bị SVT đến khoa cấp cứu hàng năm, [32] các bác sĩ cấp cứu có thể là người đầu tiên đánh giá bệnh nhân có nhịp tim nhanh cơ chế chưa được biết và có cơ hội để chẩn đoán các cơ chế rối loạn nhịp tim. Điều quan trọng cần ghi ECG 12 chuyển đạo để phân biệt các cơ chế nhịp tim nhanh tuy theo nút AV có là thành phần bắt buộc hay không (mục 2.3.2), vì điều trị nhắm vào nút AV sẽ không đáng tin cậy để cắt nhịp nhanh nếu nhịp nhanh không phụ thuộc vào nút AV.

KC-1: Các khuyến cáo điều trị cấp thời SVT cơ chế chưa rõ

|

COR |

LOE |

Các khuyến cáo |

|---|---|---|

|

I |

B-R |

1. Các thủ thuật cường phế vị được khuyến cáo điều trị cấp thời cho các bệnh nhân SVT đều.[33-35] |

|

I |

B-R |

2. Adenosine được khuyến cáo điều trị cấp thời cho các bệnh nhân có SVT đền.[34, 36-43] |

|

I |

B-NR |

3. Chuyển nhịp đồng bộ bằng điện được khuyến cáo điều trị cấp thời cho các bệnh nhân có SVT huyết động không ổn định khi các thủ thuật cường phế vị hoặc adenosine không hiệu quả hoặc không thể thực hiện.[44] |

|

I |

B-NR |

4. Chuyển nhịp đồng bộ bằng điện được khuyến cáo cho điều trị cấp thời ở các bệnh nhân có SVT huyết động không ổn định khi điều trị thuốc không hiệu quả hoặc chống chỉ định. [36,45] |

|

IIa |

B-R |

1. Diltiazem hoặc verapamil tĩnh mạch có thể có hiệu quả để điều trị cấp thời ở các bệnh nhân SVT huyết động ổn định [35,39,42,46]. |

|

IIa |

C-LD |

2. Beta blockers phù hợp cho điều trị cấp thời các bệnh nhân SVT huyết động ổn định [47]. |

2.4.2. Điều chỉnh tiếp tục: Các khuyến cáo (Xem KC-2)

Các khuyến cáo và thuật toán (Hình 3) điều chỉnh tiếp tục, cùng với các khuyến cáo khác và các thuật toán cho SVTs cụ thể tiếp theo, có nghĩa gồm việc xem xét các sở thích bệnh nhân và đánh giá lâm sàng; điều này có thể bao gồm việc xem xét các ý kiến của bác sĩ tim mạch hoặc nhà điện sinh lý lâm sàng tim, cũng như bệnh nhân an tâm với chẩn đoán xâm lấn và can thiệp điều trị có thể. Khuyến cáo cho lựa chọn điều trị (bao gồm cả điều trị bằng thuốc, triệt phá, hoặc theo dõi) phải được xem xét trong bối cảnh của tần số và khoảng thời gian của SVT, cùng với biểu hiện lâm sàng, chẳng hạn như các triệu chứng hay hậu quả bất lợi (ví dụ, sự phát triển của bệnh cơ tim).

KC-2: Các khuyến cáo cho điều chỉnh tiếp tục SVT cơ chế chưa rõ

|

COR |

LOE |

Các khuyến cáo |

|---|---|---|

|

I |

B-R |

1. Beta blockers, diltiazem, hoặc verapamil uống là hữu ích cho điều chỉnh liên tục ỏ các bệnh nhân SVT có triệu chứng không có kích thích sớm trong quá trình nhịp xoang [48.50] . |

|

I |

B-NR |

2. Nghiên cứu điện sinh lý (EP) với sự lựa chọn triệt phá là hữu ích để chẩn đoán và điều trị có khả năng SVT [51,58]. |

|

I |

C-LD |

3. Các bệnh nhân có SVT nên được giáo dục về thực hiện thủ thuật cường phế vị như thế nào để điều trị SVT tiếp theo [33]. |

|

IIa |

B-R |

1. Flecainide hoặc propafenone phù hợp để điều trị liên tục các bệnh nhân không có bệnh tim thực thể hoặc bệnh cơ tim thiếu máu có SVT có triệu chứng và không là ứng viên hoặc không thích thực hiện triệt phá qua catheter [48,59-65] |

|

IIb |

B-R |

1. Sotalol có thể phù hợp cho điều chỉnh tiếp tục các bệnh nhân SVT có triệu chứng không là ứng viên hoặc không thích thực hiện triệt phá qua catheter.[66] |

|

IIb |

B-R |

2. Dofetilide có thể là phù hợp cho điều chỉnh liên tục các bệnh nhân có SVT có triệu chứng không là ứng viên hoặc không thích thực hiện triệt phá qua catheter và ở các bệnh nhân này beta blockers, diltiazem, flecainide, propafenone, hoặc verapamil không có hiệu quả hoặc chống chỉ định [59]. |

|

IIb |

C-LD |

3. Amiodarone uống có thể được xem xét để điều chỉnh tiếp tục các bệnh nhân SVT có triệu chứng không là ứng viên hoặc không thích can thiếp qua catheter và các bệnh nhân này beta blockers, diltiazem, dofetilide, flecainide, propafenone, sotalol, hoặc verapamil không hiệu quả hoặc chống chỉ định [67]. |

|

IIb |

C-LD |

4. Digoxin uống có thể phù hợp cho điều chỉnh tiếp tục các bệnh nhân SVT có triệu chứng không có kích thích sớm, không là ứng viên hoặc không thích thực hiện triệt phá qua catheter [50]. |

2.5. Các nguyên tắc cơ bản cho nghiên cứu điện sinh lý, lập bản đồ và triệt phá

Nghiên cứu EP xâm lấn cho phép chẩn đoán chính xác cơ chế rối loạn nhịp tim cơ bản và định khu vị trí nguồn gốc và cung cấp điều trị triệt để nếu kết hợp với triệt phá qua catheter. Có những tiêu chuẩn để xác định các trang thiết bị và huấn luyện nhân viên cho hiệu suất EPs tối ưu. [68] Các nghiên cứu EP liên quan đến vị trí của các catheter đa điện cực trong tim tại ≥1 vị trí trong nhĩ, thất, hoặc xoang vành. Tạo nhịp và kích thích điện có chương trình có thể được thực hiện có hoặc không có sự thúc đẩy của thuốc. Bằng cách sử dụng thủ thuật chẩn đoán trong quá trình EP, cơ chế của SVT có thể được xác định trong hầu hết các trường hợp. [31,69] Các biến chứng của EPs chẩn đoán là rất hiếm nhưng có thể đe dọa tính mạng. [70]

Bảng tỷ lệ thành công và biến chứng cho triệt phá SVT được bao gồm trong toàn văn hướng dẫn và trong các dữ liệu trực tuyến bổ sung – Phụ lục 3. Lập bản đồ tim được thực hiện trong quá trình EPs để xác định vị trí nguồn gốc rối loạn nhịp hoặc các khu vực dẫn truyền quyết định cho phép đạt đích triệt phá. Nhiều kỹ thuật đã được phát triển để mô tả sự phân bố thời gian và không gian của hoạt động điện học.[71] Một số công cụ đã được phát triển tạo thuận lợi để lập bản đồ loạn nhịp tim và triệt phá, bao gồm lập bản đồ điện – giải phẫu 3 chiều và điều hướng (navigation) từ. Lợi ích tiềm năng của các công nghệ này gồm xác định chính xác hơn hoặc định vị cơ chế loạn nhịp, hiển thị không gian của các catheter và kích hoạt loạn nhịp tim, giảm tiếp xúc quang tuyến cho bệnh nhân và nhân viên, cũng như thời gian thủ thuật rút ngắn, đặc biệt đối với loạn nhịp hoặc giải phẫu phức tạp. [72]

Quang tuyến về mặt lịch sử đã là phương thức hình ảnh đầu tiên sử dụng cho nghiên cứu điện sinh lý (EPs). Chú ý đến kỹ thuật quang tuyến tối ưu và áp dụng các chiến lược giảm xạ có thể tối thiểu liều bức xạ cho bệnh nhân và người thực hiện. Các tiêu chuẩn hiện nay để sử dụng nguyên tắc “thấp đến mức độ đạt được một cách hợp lý” (as low as reasonably achievable: ALARA) trên giả định không có ngưỡng dưới mà bức xạ ion hóa phải thoát khỏi hiệu ứng sinh học có hại. Hệ thống hình ảnh thay thế, chẳng hạn như lập bản đồ điện giải phẫu và siêu âm tim trong buồng tim, đã dẫn đến khả năng thực hiện triệt phá SVT không có hoặc quang tuyến tối thiểu, với tỷ lệ thành công và biến chứng tương tự như kỹ thuật tiêu chuẩn. [73-77] Một cách tiếp cận giảm quang tuyến là đặc biệt quan trọng ở bệnh nhân trẻ em và trong quá trình mang thai. [78,79]

Dòng tần số radio là nguồi năng lượng được sử dụng phổ biến nhất cho triệt phá SVT.[80] Triệt phá lạnh (Cryoablation) được sử dụng như là sự thay thế cho triệt phá tần số radio để làm tối thiểu tổn thương đối với nút AV trong quá trình triệt phá loạn nhịp đặc biệt, như AVNRT, AT cạnh bó His , cả những đường phụ cành bó His, đặc biệt ở các quần thể bệnh nhân cụ thể, như trẻ em và người lớn còn trẻ. Lựa chọn các nguồn năng lượng phụ thuộc vào kinh nghiệm người làm, khu vực đích loạn nhịp và sở thích bệnh nhân.

3. Loạn nhịp nhanh xoang (Sinus Tachyarrhythmias)

Ở những cá thể bình thường, tần số xoang lúc nghỉ nói chung giữa 50 bpm và 90 bpm, phản ảnh trương lực phế vị (reflecting vagal tone).[81–84]Nhịp xoang nhanh được quy cho tình trạng, trong đó tần số xoang vượt quá 100 bpm. Trên ECG, sóng P đứng ở các chuyển đạo I, II, aVF và hai pha ở chuyển đạo V1.

3.1. Nhịp xoang nhanh sinh lý

Nhịp xoang nhanh sinh lý (Physiological Sinus Tachycardia) có thể do các nguyên nhân bệnh lý, gồm nhiễm trùng có sốt, mất nước, thiếu máu, suy tim và cường giáp, thêm vào các chất ngoại sinh, gồm caffeine, các thuốc có ảnh hưởng kích thích beta (như, albuterol, salmeterol), và các thuốc kích thích bị cấm (chẳng hạn, amphetamines, cocaine). Trong các trường hợp này, nhịp nhanh được cho để giải tỏa nguyên nhân nền.

3.2. Nhịp xoang nhanh không phù hợp (Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia)

Nhịp xoang nhanh không phù hợp (inappropriate sinus tachycardia: IST) được định nghĩa khi nhịp xoang nhanh không giải thích được do nhu cầu sinh lý. Rất quan trọng để định nghĩa này là sự hiện diện kết hợp, đôi khi suy nhược, các triệu chứng bao gồm suy nhược, mệt mỏi, choáng váng và cảm giác khó chịu, chẳng hạn như tim chạy đua. Bệnh nhân có IST thường thấy nhịp tim > 100 bpm và tần số trung bình > 90 bpm trong thời gian 24 giờ. [81] Nguyên nhân của IST là không rõ ràng và các cơ chế liên quan đến rối loạn tính tự động (dysautonomia), rối loạn điều hòa thần kinh hormone (nerohormonal dysregulation), cả trong cường hoạt động nút xoang nội tại (intrinsic) cũng được nêu ra. .

Điều quan trọng phải phân biệt IST với các nguyên nhân nhịp nhanh thứ phát, gồm cường giáp, thiếu máu, mất nước, đau, cả sử dụng các chất ngoại sinh. Lo âu cũng là một kích thích quan trọng, bệnh nhân có IST có thể có liên quan đến rối loạn lo âu. [81] IST cũng phải được phân biệt với các hình thức khác của nhịp nhanh, gồm AT phát sinh từ các phía trên của rìa mào (crista terminalis) và nhịp nhanh vào lại nút xoang (Phần 4 ). Nó cũng quan trọng cần phân biệt IST với hội chứng nhịp nhanh tư thế đứng, mặc dù chồng lên nhau có thể có mặt ở mỗi cá nhân. Bệnh nhân có hội chứng nhịp nhanh từ thế đứng có các triệu chứng chủ yếu liên quan đến sự thay đổi trong tư thế, điều trị để ngăn chặn tần số xoang có thể dẫn đến hạ huyết áp thế đứng nghiêm trọng. Như vậy, IST là một chẩn đoán loại trừ.

3.2.1. Điều trị cấp thời

Không có khuyến cáo chuyên biệt cho điều trị cấp thời IST.

3.2.2. Điều trị tiếp tục: Các khuyến cáo (Xem KC-3)

Do tiên lượng của IST nói chung là lành tính, điều trị giảm các triệu chứng và có thể không cần thiết. Điều trị IST khó, điều cần ghi nhận làm chậm tần số tim có thể không làm giảm được triệu chứng. Điều trị bằng beta blockers hoặc chẹn kênh canxi thường không hiệu quả do tác dụng phụ tim mạch, như hạ huyết áp. Tập luyện gắng sức có thể có lợi ích, nhưng lợi ích không được chứng minh.

KC-3: Các khuyến cáo cho điều chỉnh IST tiếp tục

|

COR |

LOE |

Các khuyến cáo |

|---|---|---|

|

I |

C-LD |

1. Đánh giá và điều trị các nguyên nhân có thẻ hồi phục được khuyến cáo ở các bệnh nhân IST được nghi ngờ.[81,101] |

|

IIa |

B-R |

1. Ivabradine phù hợp để điều trị tiếp tục các bệnh nhân IST có triệu chứng.[85–93] |

|

IIb |

C-LD |

1. Beta blockers có thể được xem xét để điều trị liên tục ở các bệnh nhân có IST có triệu chứng.[87,89] |

|

IIb |

C-LD |

2. Phối hợp beta blockers và ivabradine có thể được xem xét để điều trị tiếp tục các bệnh nhân IST.[89] |

Ivabradine là một chất ức chế kênh “I-funny” hoặc kênh “if”, các các kênh này đảm trách tính tự động của nút xoang bình thường, do đó, ivabradine làm giảm hoạt động tạo nhịp của nút xoang, gây ra chậm tần số tim. Trên cơ sở kết quả của 2 nghiên cứu ngẫu nhiên có đối chứng (RCT), thuốc này vừa mới được FDA chấp thuận để sử dụng cho các bệnh nhân có suy tim tâm thu. Thuốc không có tác dụng huyết động khác ngoài việc giảm nhịp tim. Như vậy, nó đã được nghiên cứu để sử dụng để giảm tần số xoang và cải thiện các triệu chứng liên quan đến IST. [85-93]

Triệt phá tần số radio để thay đổi nút xoang có thể giảm tần số xoang, với các tần số thành công của thủ thuật cấp thời được thông báo trong phạm vi 76% đến 100% nghiễn cứu thuần tập không ngẫu nhiên. [94-100] Tuy nhiên, các triệu chứng thường tái phát sau vài tháng, với IST tái phát lên đến 27% và tái phát toàn bộ triệu chứng (IST hoặc AT không IST) ở 45% bệnh nhân. [94,96,97,99] Các biến chứng có thể là đáng kể. Theo quan điểm về các lợi ích khiêm tốn của thủ tục này và khả năng có hại đáng kể, việc thay đổi nút xoang nên chỉ được xem xét đối với những bệnh nhân được đánh giá có triệu chứng nặng và không thể điều trị thuốc đầy đủ, và chỉ sau khi thông tin cho bệnh nhân hiểu rõ về các nguy cơ có thể sẽ lớn hơn lợi ích mà việc triệt phá mang lại…

(Còn nữa)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

1. Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Institute of Medicine (US). Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research, Institute of Medicine (US). Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011.

3. ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Methodology Manual and Policies From the ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association. 2010. Available at: http://assets.cardiosource.com/Methodology_Manual_for_ACC_AHA_Writing_Committees.pdf and http://my.americanheart.org/idc/groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/documents/downloadable/ucm_319826.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2015.

4. Jacobs AK, Kushner FG, Ettinger SM, et al. ACCF/AHA clinical practice guideline methodology summit report: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:268–310. FREE Full Text

5. Jacobs AK, Anderson JL, Halperin JL. The evolution and future of ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines: a 30-year journey: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:1208–17. FREE Full Text

6. Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, et al. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:2329–45. FREE Full Text

7. Halperin JL, Levine GN, Al-Khatib SM. Further evolution of the ACC/AHA clinical practice guideline recommendation classification system: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2016;133:1426–28. FREE Full Text

8. Arnett DK, Goodman RA, Halperin JL, et al. AHA/ACC/HHS strategies to enhance application of clinical practice guidelines in patients with cardiovascular disease and comorbid conditions: from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and US Department of Health and Human Services. Circulation. 2014;130:1662–7. FREE Full Text

9. Page RL, Joglar JA, Al-Khatib SM, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2016;133:e506–74. FREE Full Text

10. Al-Khatib SM, Arshad A, Balk EM, et al. Risk stratification for arrhythmic events in patients with asymptomatic pre-excitation: a systematic review for the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society [published ahead of print September 23, 2015]. Circulation. 2015; IN PRESS. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000309. Google Scholar

11. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:e199–267. FREE Full Text

12. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Supraventricular Arrhythmias). Developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2003;108:1871–909. FREE Full Text

13. Orejarena LA, Vidaillet H, DeStefano F, et al. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:150–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

14. Lu C-W, Wu M-H, Chen H-C, et al. Epidemiological profile of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in a general population younger than 50 years of age in an era of radiofrequency catheter ablation. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174:530–4. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

15. Whinnett ZI, Sohaib SMA, Davies DW. Diagnosis and management of supraventricular tachycardia. BMJ. 2012;345:e7769. FREE Full Text

16. Porter MJ, Morton JB, Denman R, et al. Influence of age and gender on the mechanism of supraventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:393–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

17. Goyal R, Zivin A, Souza J, et al. Comparison of the ages of tachycardia onset in patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia and accessory pathway-mediated tachycardia. Am Heart J. 1996;132:765–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

18. Maryniak A, Bielawska A, Bieganowska K, et al. Does atrioventricular reentry tachycardia (AVRT) or atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia (AVNRT) in children affect their cognitive and emotional development? Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34:893–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

19. González-Torrecilla E, Almendral J, Arenal A, et al. Combined evaluation of bedside clinical variables and the electrocardiogram for the differential diagnosis of paroxysmal atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardias in patients without pre-excitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2353–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

20. Liu S, Yuan S, Hertervig E, et al. Gender and atrioventricular conduction properties of patients with symptomatic atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Electrocardiol. 2001;34:295–301. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

21. Anand RG, Rosenthal GL, Van Hare GF, et al. Is the mechanism of supraventricular tachycardia in pediatrics influenced by age, gender or ethnicity? Congenit Heart Dis. 2009;4:464–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

22. Walfridsson U, Strömberg A, Janzon M, et al. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia in a Swedish population: consequences on health-related quality of life. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:1299–306. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

23. Cain N, Irving C, Webber S, et al. Natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome diagnosed in childhood. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:961–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

24. Laurent G, Leong-Poi H, Mangat I, et al. Influence of ventriculoatrial timing on hemodynamics and symptoms during supraventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:176–81. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

25.↵ Auricchio A, Klein H, Trappe HJ, et al. Lack of prognostic value of syncope in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:152–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

26. Drago F, Turchetta A, Calzolari A, et al. Reciprocating supraventricular tachycardia in children: low rate at rest as a major factor related to propensity to syncope during exercise. Am Heart J. 1996;132:280–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

27. Kalusche D, Ott P, Arentz T, et al. AV nodal re-entry tachycardia in elderly patients: clinical presentation and results of radiofrequency catheter ablation therapy. Coron Artery Dis. 1998;9:359–63. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

28. Haghjoo M, Arya A, Heidari A, et al. Electrophysiologic characteristics and results of radiofrequency catheter ablation in elderly patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. J Electrocardiol. 2007;40:208–13. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

29. Walfridsson U, Walfridsson H. The impact of supraventricular tachycardias on driving ability in patients referred for radiofrequency catheter ablation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:191–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

30. Letsas KP, Weber R, Siklody CH, et al. Electrocardiographic differentiation of common type atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia from atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia via a concealed accessory pathway. Acta Cardiol. 2010;65:171–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

31. Knight BP, Ebinger M, Oral H, et al. Diagnostic value of tachycardia features and pacing maneuvers during paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:574–82. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

32. Murman DH, McDonald AJ, Pelletier AJ, et al. US emergency department visits for supraventricular tachycardia, 1993–2003. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:578–81. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

33. Lim SH, Anantharaman V, Teo WS, et al. Comparison of treatment of supraventricular tachycardia by Valsalva maneuver and carotid sinus massage. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:30–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

34. Luber S, Brady WJ, Joyce T, et al. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia: outcome after ED care. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:40–2. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

35. Waxman MB, Wald RW, Sharma AD, et al. Vagal techniques for termination of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol. 1980;46:655–64. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

36. Brady WJ, DeBehnke DJ, Wickman LL, et al. Treatment of out-of-hospital supraventricular tachycardia: adenosine vs verapamil. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:574–85. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

37. Cairns CB, Niemann JT. Intravenous adenosine in the emergency department management of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:717–21. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

38. Gausche M, Persse DE, Sugarman T, et al. Adenosine for the prehospital treatment of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:183–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

39. Madsen CD, Pointer JE, Lynch TG. A comparison of adenosine and verapamil for the treatment of supraventricular tachycardia in the prehospital setting. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:649–55. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

40. McCabe JL, Adhar GC, Menegazzi JJ, et al. Intravenous adenosine in the prehospital treatment of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:358–61. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

41. Rankin AC, Oldroyd KG, Chong E, et al. Value and limitations of adenosine in the diagnosis and treatment of narrow and broad complex tachycardias. Br Heart J. 1989;62:195–203. Abstract/FREE Full Text

42. Lim SH, Anantharaman V, Teo WS, et al. Slow infusion of calcium channel blockers compared with intravenous adenosine in the emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardia. Resuscitation. 2009;80:523–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

43. DiMarco JP, Miles W, Akhtar M, et al. Adenosine for paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia: dose ranging and comparison with verapamil. Assessment in placebo-controlled, multicenter trials. The Adenosine for PSVT Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:104–10. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

44. Roth A, Elkayam I, Shapira I, et al. Effectiveness of prehospital synchronous direct-current cardioversion for supraventricular tachyarrhythmias causing unstable hemodynamic states. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:489–91. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

45. Stec S, Kryñski T, Kułakowski P,. Efficacy of low energy rectilinear biphasic cardioversion for regular atrial tachyarrhythmias. Cardiol J. 2011;18:33–8. MedlineGoogle Scholar

46. Lim SH, Anantharaman V, Teo WS. Slow-infusion of calcium channel blockers in the emergency management of supraventricular tachycardia. Resuscitation. 2002;52:167–74. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

47. Gupta A, Naik A, Vora A, et al. Comparison of efficacy of intravenous diltiazem and esmolol in terminating supraventricular tachycardia. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:969–72. MedlineGoogle Scholar

48. Dorian P, Naccarelli GV, Coumel P, et al. A randomized comparison of flecainide versus verapamil in paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. The Flecainide Multicenter Investigators Group. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:89A–95A. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

49. Mauritson DR, Winniford MD, Walker WS, et al. Oral verapamil for paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia: a long-term, double-blind randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:409–12. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

50. Winniford MD, Fulton KL, Hillis LD. Long-term therapy of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia: a randomized, double-blind comparison of digoxin, propranolol and verapamil. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:1138–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

51. Jackman WM, Beckman KJ, McClelland JH, et al. Treatment of supraventricular tachycardia due to atrioventricular nodal reentry, by radiofrequency catheter ablation of slow-pathway conduction. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:313–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

52. Hindricks G. The Multicentre European Radiofrequency Survey (MERFS): complications of radiofrequency catheter ablation of arrhythmias. The Multicentre European Radiofrequency Survey (MERFS) investigators of the Working Group on Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:1644–53. Abstract/FREE Full Text

53. Hindricks G. Incidence of complete atrioventricular blốc following attempted radiofrequency catheter modification of the atrioventricular node in 880 patients. Results of the Multicenter European Radiofrequency Survey (MERFS) The Working Group on Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:82–8. Abstract/FREE Full Text

54. Spector P, Reynolds MR, Calkins H, et al. Meta-analysis of ablation of atrial flutter and supraventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:671–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

55. Calkins H, Yong P, Miller JM, et al. Catheter ablation of accessory pathways, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, and the atrioventricular junction: final results of a prospective, multicenter clinical trial. The Atakr Multicenter Investigators Group. Circulation. 1999;99:262–70. Abstract/FREE Full Text

56. Scheinman MM, Huang S. The 1998 NASPE prospective catheter ablation registry. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:1020–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

57. Cheng CH, Sanders GD, Hlatky MA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation for supraventricular tachycardia. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:864–76. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

58. Bohnen M, Stevenson WG, Tedrow UB, et al. Incidence and predictors of major complications from contemporary catheter ablation to treat cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1661–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

59. Tendera M, Wnuk-Wojnar AM, Kulakowski P, et al. Efficacy and safety of dofetilide in the prevention of symptomatic episodes of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia: a 6-month double-blind comparison with propafenone and placebo. Am Heart J. 2001;142:93–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

60. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of propafenone in the prophylaxis of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. UK Propafenone PSVT Study Group. Circulation. 1995;92:2550–7. Medline

61. Chimienti M, Cullen MT, Casadei G. Safety of flecainide versus propafenone for the long-term management of symptomatic paroxysmal supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Report from the Flecainide and Propafenone Italian Study (FAPIS) Group. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:1943–51. Abstract/FREE Full Text

62. Anderson JL, Platt ML, Guarnieri T, et al. Flecainide acetate for paroxysmal supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. The Flecainide Supraventricular Tachycardia Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:578–84. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

63. Pritchett EL, DaTorre SD, Platt ML, et al. Flecainide acetate treatment of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: dose-response studies. The Flecainide Supraventricular Tachycardia Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:297–303. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

64. Pritchett EL, McCarthy EA, Wilkinson WE. Propafenone treatment of symptomatic paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias. A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in patients tolerating oral therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:539–44. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

65. Henthorn RW, Waldo AL, Anderson JL, et al. Flecainide acetate prevents recurrence of symptomatic paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. The Flecainide Supraventricular Tachycardia Study Group. Circulation. 1991;83:119–25. Abstract/FREE Full Text

66. Wanless RS, Anderson K, Joy M, et al. Multicenter comparative study of the efficacy and safety of sotalol in the prophylactic treatment of patients with paroxysmal supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Am Heart J. 1997;133:441–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

67. Gambhir DS, Bhargava M, Nair M, et al. Comparison of electrophysiologic effects and efficacy of single-dose intravenous and long-term oral amiodarone therapy in patients with AV nodal reentrant tachycardia. Indian Heart J. 1996;48:133–7. MedlineGoogle Scholar

68. Haines DE, Beheiry S, Akar JG, et al. Heart Rythm Society expert consensus statement on electrophysiology laboratory standards: process, protocols, equipment, personnel, and safety. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:e9–51. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

69. Knight BP, Zivin A, Souza J, et al. A technique for the rapid diagnosis of atrial tachycardia in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:775–81. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

70. Horowitz LN, Kay HR, Kutalek SP, et al. Risks and complications of clinical cardiac electrophysiologic studies: a prospective analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9:1261–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

71. Asirvatham S, Narayan O. Advanced catheter mapping and navigation system. In: Huang SW, Wood M, editors. Catheter Ablation of Cardiac Arrhythmias. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2006:135–61. Google Scholar

72. Sporton SC, Earley MJ, Nathan AW, et al. Electroanatomic versus fluoroscopic mapping for catheter ablation procedures: a prospective randomized study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:310–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

73. Alvarez M, Tercedor L, Almansa I, et al. Safety and feasibility of catheter ablation for atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia without fluoroscopic guidance. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1714–20. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

74. Casella M, Pelargonio G, Dello RA, et al. “Near-zero” fluoroscopic exposure in supraventricular arrhythmia ablation using the EnSite NavX mapping system: personal experience and review of the literature. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2011;31:109–18. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

75. Razminia M, Manankil MF, Eryazici PLS, et al. Nonfluoroscopic catheter ablation of cardiac arrhythmias in adults: feasibility, safety, and efficacy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:1078–86. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

76. Earley MJ, Showkathali R, Alzetani M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of arrhythmias guided by non-fluoroscopic catheter location: a prospective randomized trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1223–9. Abstract/FREE Full Text

77. Hindricks G, Willems S, Kautzner J, et al. Effect of electroanatomically guided versus conventional catheter ablation of typical atrial flutter on the fluoroscopy time and resource use: a prospective randomized multicenter study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:734–40. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

78. Xu D, Yang B, Shan Q, et al. Initial clinical experience of remote magnetic navigation system for catheter mapping and ablation of supraventricular tachycardias. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2009;25:171–4. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

79. Sommer P, Wojdyla-Hordynska A, Rolf S, et al. Initial experience in ablation of typical atrial flutter using a novel three-dimensional catheter tracking system. Europace. 2013;15:578–81. Abstract/FREE Full Text

80. Cummings JE, Pacifico A, Drago JL, et al. Alternative energy sources for the ablation of arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:434–43. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

81. Olshansky B, Sullivan RM. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:793–801. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

82. Marcus B, Gillette PC, Garson A. Intrinsic heart rate in children and young adults: an index of sinus node function isolated from autonomic control. Am Heart J. 1990;119:911–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

83. Jose AD, Collison D. The normal range and determinants of the intrinsic heart rate in man. Cardiovasc Res. 1970;4:160–7. Abstract/FREE Full Text

84. Alboni P, Malcarne C, Pedroni P, et al. Electrophysiology of normal sinus node with and without autonomic blốcade. Circulation. 1982;65:1236–42. FREE Full Text

85. Cappato R, Castelvecchio S, Ricci C, et al. Clinical efficacy of ivabradine in patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1323–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

86. Benezet-Mazuecos J, Rubio JM, Farré J, et al. Long-term outcomes of ivabradine in inappropriate sinus tachycardia patients: appropriate efficacy or inappropriate patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36:830–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

87. Ptaszynski P, Kaczmarek K, Ruta J, et al. Metoprolol succinate vs. ivabradine in the treatment of inappropriate sinus tachycardia in patients unresponsive to previous pharmacological therapy. Europace. 2013;15:116–21. Abstract/FREE Full Text

88. Ptaszynski P, Kaczmarek K, Ruta J, et al. Ivabradine in the treatment of inappropriate sinus tachycardia in patients after successful radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrioventricular node slow pathway. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36:42–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

89. Ptaszynski P, Kaczmarek K, Ruta J, et al. Ivabradine in combination with metoprolol succinate in the treatment of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2013;18:338–44. Abstract/FREE Full Text

90. Calò L, Rebecchi M, Sette A, et al. Efficacy of ivabradine administration in patients affected by inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1318–23. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

91. Kaplinsky E, Comes FP, Urondo LSV, et al. Efficacy of ivabradine in four patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia: a three month-long experience based on electrocardiographic, Holter monitoring, exercise tolerance and quality of life assessments. Cardiol J. 2010;17:166–71. MedlineGoogle Scholar

92. Rakovec P. Treatment of inappropriate sinus tachycardia with ivabradine. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2009;121:715–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

93. Zellerhoff S, Hinterseer M, Felix Krull B, et al. Ivabradine in patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;382:483–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

94. Man KC, Knight B, Tse HF, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia guided by activation mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:451–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

95. Lin D, Garcia F, Jacobson J, et al. Use of noncontact mapping and saline-cooled ablation catheter for sinus node modification in medically refractory inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:236–42. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

96. Lee RJ, Kalman JM, Fitzpatrick AP, et al. Radiofrequency catheter modification of the sinus node for “inappropriate” sinus tachycardia. Circulation. 1995;92:2919–28. Abstract/FREE Full Text

97. Marrouche NF, Beheiry S, Tomassoni G, et al. Three-dimensional nonfluoroscopic mapping and ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Procedural strategies and long-term outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1046–54. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

98. Callans DJ, Ren JF, Schwartzman D, et al. Narrowing of the superior vena cava-right atrium junction during radiofrequency catheter ablation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia: analysis with intracardiac echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1667–70. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

99. Frankel DS, Lin D, Anastasio N, et al. Frequent additional tachyarrhythmias in patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia undergoing sinus node modification: an important cause of symptom recurrence. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:835–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

100. Takemoto M, Mukai Y, Inoue S, et al. Usefulness of non-contact mapping for radiofrequency catheter ablation of inappropriate sinus tachycardia: new procedural strategy and long-term clinical outcome. Intern Med. 2012;51:357–62. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

101. Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:501–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

102. Steinbeck G, Hoffmann E. True atrial tachycardia. Eur Heart J. 1998; 19 Suppl E:E48–9. Google Scholar

103. Wren C. Incessant tachycardias. Eur Heart J. 1998;19 Suppl E:E54–9. Google Scholar

104. Medi C, Kalman JM, Haqqani H, et al. Tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy secondary to focal atrial tachycardia: long-term outcome after catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1791–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

105. Tang CW, Scheinman MM, Van Hare GF, et al. Use of P wave configuration during atrial tachycardia to predict site of origin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1315–24. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

106. Kistler PM, Roberts-Thomson KC, Haqqani HM, et al. P-wave morphology in focal atrial tachycardia: development of an algorithm to predict the anatomic site of origin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1010–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

107. Chen SA, Chiang CE, Yang CJ, et al. Sustained atrial tachycardia in adult patients. Electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological response, possible mechanisms, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 1994;90:1262–78. Abstract/FREE Full Text

108. Kalman JM, Olgin JE, Karch MR, et al. “Cristal tachycardias”: origin of right atrial tachycardias from the crista terminalis identified by intracardiac echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:451–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

109. Morton JB, Sanders P, Das A, et al. Focal atrial tachycardia arising from the tricuspid annulus: electrophysiologic and electrocardiographic characteristics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:653–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

110. Kistler PM, Sanders P, Fynn SP, et al. Electrophysiological and electrocardiographic characteristics of focal atrial tachycardia originating from the pulmonary veins: acute and long-term outcomes of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 2003;108:1968–75. Abstract/FREE Full Text

111. Kistler PM, Sanders P, Hussin A, et al. Focal atrial tachycardia arising from the mitral annulus: electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic characterization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:2212–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

112. Gonzalez MD, Contreras LJ, Jongbloed MRM, et al. Left atrial tachycardia originating from the mitral annulus-aorta junction. Circulation. 2004;110:3187–92. Abstract/FREE Full Text

113. Kistler PM, Fynn SP, Haqqani H, et al. Focal atrial tachycardia from the ostium of the coronary sinus: electrocardiographic and electrophysiological characterization and radiofrequency ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1488–93. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

114. Ouyang F, Ma J, Ho SY, et al. Focal atrial tachycardia originating from the non-coronary aortic sinus: electrophysiological characteristics and catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:122–31. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

115. Roberts-Thomson KC, Kistler PM, Haqqani HM, et al. Focal atrial tachycardias arising from the right atrial appendage: electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic characteristics and radiofrequency ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:367–72. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

116. Biviano AB, Bain W, Whang W, et al. Focal left atrial tachycardias not associated with prior catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: clinical and electrophysiological characteristics. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:17–27. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

117. Walters TE, Kistler PM, Kalman JM. Radiofrequency ablation for atrial tachycardia and atrial flutter. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21:386–94. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

118. Lee G, Sanders P, Kalman JM. Catheter ablation of atrial arrhythmias: state of the art. Lancet. 2012;380:1509–19. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

119. Gillette PC, Garson A Jr.. Electrophysiologic and pharmacologic characteristics of automatic ectopic atrial tachycardia. Circulation. 1977;56:571–5. FREE Full Text

120. Mehta AV, Sanchez GR, Sacks EJ, et al. Ectopic automatic atrial tachycardia in children: clinical characteristics, management and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:379–85. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

121. Markowitz SM, Stein KM, Mittal S, et al. Differential effects of adenosine on focal and macroreentrant atrial tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:489–502. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

122. Reisinger J, Gstrein C, Winter T, et al. Optimization of initial energy for cardioversion of atrial tachyarrhythmias with biphasic shocks. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:159–65. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

123. Engelstein ED, Lippman N, Stein KM, et al. Mechanism-specific effects of adenosine on atrial tachycardia. Circulation. 1994;89:2645–54. Abstract/FREE Full Text

124. Eidher U, Freihoff F, Kaltenbrunner W, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibutilide for the conversion of monomorphic atrial tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:358–62. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

125. de Loma-Osorio F, Diaz-Infante E, et al. Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry. 12th Official Report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Electrophysiology and Arrhythmias (2012). Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2013;66:983–92. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

126. Liu X, Dong J, Ho SY, et al. Atrial tachycardia arising adjacent to noncoronary aortic sinus: distinctive atrial activation patterns and anatomic insights. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:796–804. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

127. Creamer JE, Nathan AW, Camm AJ. Successful treatment of atrial tachycardias with flecainide acetate. Br Heart J. 1985;53:164–6. Abstract/FREE Full Text

128. Kunze KP, Kuck KH, Schlüter M, et al. Effect of encainide and flecainide on chronic ectopic atrial tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:1121–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

129. von Bernuth G, Engelhardt W, Kramer HH, et al. Atrial automatic tachycardia in infancy and childhood. Eur Heart J. 1992;13:1410–5. Abstract/FREE Full Text

130. Lucet V, Do Ngoc D, Fidelle J, et al. [Anti-arrhythmia efficacy of propafenone in children. Apropos of 30 cases]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1987;80:1385–93. MedlineGoogle Scholar

131. Heusch A, Kramer HH, Krogmann ON, et al. Clinical experience with propafenone for cardiac arrhythmias in the young. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:1050–6. Abstract/FREE Full Text

132. Colloridi V, Perri C, Ventriglia F, et al. Oral sotalol in pediatric atrial ectopic tachycardia. Am Heart J. 1992;123:254–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

133. Guccione P, Paul T, Garson A Jr.. Long-term follow-up of amiodarone therapy in the young: continued efficacy, unimpaired growth, moderate side effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1118–24. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

134. Coumel P, Fidelle J. Amiodarone in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias in children: one hundred thirty-five cases. Am Heart J. 1980;100:1063–9. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

135. Miyazaki A, Ohuchi H, Kurosaki K, et al. Efficacy and safety of sotalol for refractory tachyarrhythmias in congenital heart disease. Circ J. 2008;72:1998–2003. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

136. Kang KT, Etheridge SP, Kantoch MJ, et al. Current management of focal atrial tachycardia in children: a multicenter experience. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:664–70. Abstract/FREE Full Text

137. Wang K, Goldfarb BL, Gobel FL, et al. Multifocal atrial tachycardia. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:161–4. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

138. Bittar G, Friedman HS. The arrhythmogenicity of theophylline. A multivariate analysis of clinical determinants. Chest. 1991;99:1415–20. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

139. Iseri LT, Fairshter RD, Hardemann JL, et al. Magnesium and potassium therapy in multifocal atrial tachycardia. Am Heart J. 1985;110:789–94. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

140. Kastor JA. Multifocal atrial tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1713–7. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

141. Arsura EL, Solar M, Lefkin AS, et al. Metoprolol in the treatment of multifocal atrial tachycardia. Crit Care Med. 1987;15:591–4. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

142. Levine JH, Michael JR, Guarnieri T. Treatment of multifocal atrial tachycardia with verapamil. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:21–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

143. Salerno DM, Anderson B, Sharkey PJ, et al. Intravenous verapamil for treatment of multifocal atrial tachycardia with and without calcium pretreatment. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:623–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

144. Hazard PB, Burnett CR. Verapamil in multifocal atrial tachycardia. Hemodynamic and respiratory changes. Chest. 1987;91:68–70. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

145. Hazard PB, Burnett CR. Treatment of multifocal atrial tachycardia with metoprolol. Crit Care Med. 1987;15:20–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

146. Mehta D, Wafa S, Ward DE, et al. Relative efficacy of various physical manoeuvres in the termination of junctional tachycardia. Lancet. 1988;1:1181–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

147. Wen ZC, Chen SA, Tai CT, et al. Electrophysiological mechanisms and determinants of vagal maneuvers for termination of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1998;98:2716–23. Abstract/FREE Full Text

148. Glatter KA, Cheng J, Dorostkar P, et al. Electrophysiologic effects of adenosine in patients with supraventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1999;99:1034–40. Abstract/FREE Full Text

149. Dougherty AH, Jackman WM, Naccarelli GV, et al. Acute conversion of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia with intravenous diltiazem. IV Diltiazem Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:587–92. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

150. Waxman HL, Myerburg RJ, Appel R, et al. Verapamil for control of ventricular rate in paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation or flutter: a double-blind randomized cross-over study. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:1–6. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

151. Amsterdam EA, Kulcyski J, Ridgeway MG,. Efficacy of cardioselective beta-adrenergic blốcade with intravenously administered metoprolol in the treatment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:714–8. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

152. Das G, Tschida V, Gray R, et al. Efficacy of esmolol in the treatment and transfer of patients with supraventricular tachyarrhythmias to alternate oral antiarrhythmic agents. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;28:746–50. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

153. Alboni P, Tomasi C, Menozzi C, et al. Efficacy and safety of out-of-hospital self-administered single-dose oral drug treatment in the management of infrequent, well-tolerated paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:548–53. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

154. Yeh SJ, Lin FC, Chou YY, et al. Termination of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia with a single oral dose of diltiazem and propranolol. Circulation. 1985;71:104–9. Abstract/FREE Full Text

155. Rinkenberger RL, Prystowsky EN, Heger JJ, et al. Effects of intravenous and chronic oral verapamil administration in patients with supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation. 1980;62:996–1010. FREE Full Text

156. DEste D, Zoppo F, Bertaglia E, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with atrioventricular node reentrant tachycardia. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:350–3. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

157. Langberg JJ, Leon A, Borganelli M, et al. A randomized, prospective comparison of anterior and posterior approaches to radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia. Circulation. 1993;87:1551–6. Abstract/FREE Full Text

158. Kalbfleisch SJ, Strickberger SA, Williamson B, et al. Randomized comparison of anatomic and electrogram mapping approaches to ablation of the slow pathway of atrioventricular node reentrant tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:716–23. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

159. Kay GN, Epstein AE, Dailey SM, et al. Selective radiofrequency ablation of the slow pathway for the treatment of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. Evidence for involvement of perinodal myocardium within the reentrant circuit. Circulation. 1992;85:1675–88. Abstract/FREE Full Text

160. Bogun F, Knight B, Weiss R, et al. Slow pathway ablation in patients with documented but noninducible paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1000–4. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

161. OHara GE, Philippon F, Champagne J, et al. Catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias: a 14-year experience with 5330 consecutive patients at the Quebec Heart Institute, Laval Hospital. Can J Cardiol. 2007; 23 Suppl B:67B–70B. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

162. Gambhir DS, Bhargava M, Arora R, et al. Electrophysiologic effects and therapeutic efficacy of intravenous flecainide for termination of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Indian Heart J. 1995;47:237–43. MedlineGoogle Scholar

163. Musto B, Cavallaro C, Musto A, et al. Flecainide single oral dose for management of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in children and young adults. Am Heart J. 1992;124:110–5. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar

164. Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953–1989. Circulation. 1993;87:866–73. Abstract/FREE Full Text

165. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. Wolff-Parkinson-white syndrome in the era of catheter ablation: insights from a registry study of 2169 patients. Circulation. 2014;130:811–9. Abstract/FREE Full Text

166. Timmermans C, Smeets JL, Rodriguez LM, et al. Aborted sudden death in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:492–4. CrossRefMedlineGoogle Scholar