VAI TRÒ NỀN TẢNG CỦA ĐIỀU TRỊ NỘI KHOA TỐI ƯU

Với chứng cứ từ những thử nghiệm lâm sàng đã đề cập ở trên, điều trị nội khoa tối ưu có vai trò nền tảng và quan trọng ở bệnh nhân bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định.

ThS. BS TRẦN CÔNG DUY

TS. BS HOÀNG VĂN SỸ

Bộ môn Nội Tổng Quát, Đại học Y Dược TP. Hồ Chí Minh

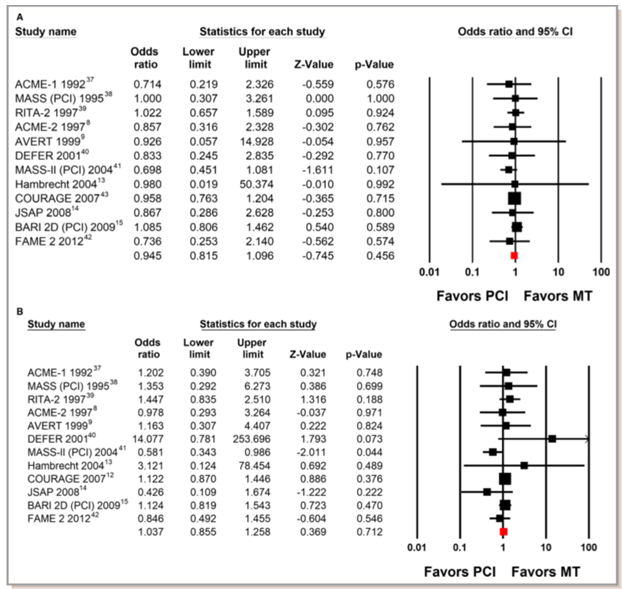

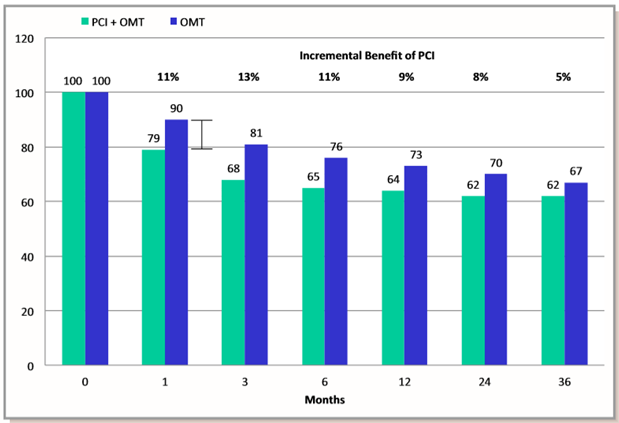

Can thiệp mạch vành qua da không chứng minh được tính ưu thế trong việc giảm các biến cố tim mạch so với điều trị nội khoa tối ưu đơn thuần trong các nghiên cứu MASS-II, COURAGE, BARI 2D …, ngay cả ở các bệnh nhân nguy cơ cao như đái tháo đường, tổn thương đoạn gần động mạch xuống trước trái, giảm phân suất tống máu thất trái, lớn tuổi, bệnh thận mạn …Ngoài ra, điều trị nội khoa tối ưu giảm triệu chứng đau thắt ngực không thua kém CTMVQD qua kết quả của nghiên cứu ORBITA được xuất bản gần đây. Vì những lý do đó, điều trị nội khoa tối ưu mang tính cốt lõi trong chiến lược điều trị và chỉ CTMVQD trong một số trường hợp có chỉ định mang lợi ích thực sự cho bệnh nhân.

Mục tiêu của điều trị bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định là giảm triệu chứng và cải thiện tiên lượng. Chiến lược điều trị bao gồm thay đổi lối sống, kiểm soát các yếu tố bệnh động mạch vành, điều trị thuốc dựa vào chứng cứ và giáo dục bệnh nhân. Điều trị nội khoa có thể đạt cả hai mục tiêu của bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định là giảm đau thắt ngực và ngăn ngừa các biến cố tim mạch. Thế nào là điều trị nội khoa tối ưu ở bệnh nhân bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định? Theo khuyến cáo của Hội Tim Châu Âu năm 2013, điều trị nội khoa tối ưu gồm ít nhất một thuốc giảm đau thắt ngực/thiếu máu cục bộ cơ tim và các thuốc phòng ngừa các biến cố tim mạch (mức độ khuyến cáo: I) [2].

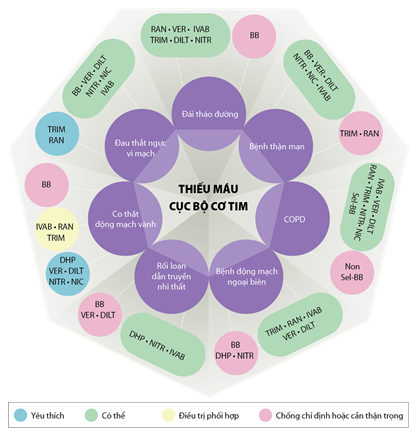

Giảm triệu chứng đau thắt ngực: các thuốc chống đau thắt ngực cùng với thay đổi lối sống, tập thể dục thường xuyên và giáo dục bệnh nhân có thể giảm thiểu hoặc loại trừ triệu chứng dài hạn. Vì tất cả các thuốc chống đau thắt ngực (ức chế beta, ức chế canxi, nitrat, trimetazidine, ivabradine, nicorandil và ranolazine) có hiệu quả và mức độ chứng cứ tương đương nhau nên chúng ta cần loại trừ quan điểm thuốc hàng thứ nhất hay hàng thứ hai mà thay vào đó, các thuốc này xếp hàng ngang nhau. Hơn nữa, bệnh nhân bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định có một số bệnh đồng mắc và đau thắt ngực có thể do nhiều cơ chế sinh lý bệnh khác nhau. Ngoài tác dụng giảm đau ngực, một số thuốc có các đặc tính phụ có thể hữu ích, phụ thuộc vào bệnh đồng mắc và các cơ chế của bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định. Đã đến lúc chúng ta cần đề xuất một cách tiếp cận mới khác biệt, cá thể hóa dành cho các bệnh nhân dựa vào đặc điểm lâm sàng, bệnh đồng mắc và cơ chế sinh lý bệnh: tiếp cận ‘kim cương’(phương pháp này được xuất bản vào năm 2018 do nhóm chuyên gia gồm Ferrari R và cộng sự với nhiều kinh nghiệm và quan tâm về bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định đã họp tại Đại học Ferrara, Italy đề xuất). Phương pháp tiếp cận ‘kim cương’ có thể phù hợp hơn các khuyến cáo hiện tại để hướng dẫn các bác sĩ lâm sàng chọn lựa chế độ thuốc thích hợp nhất trong đơn trị liệu hoặc phối hợp thuốc đối với từng bệnh nhân (Hình 5, 6).

Phòng ngừa các biến cố tim mạch: những nỗ lực phòng ngừa nhồi máu cơ tim và tử vong trong bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định tập trung chủ yếu vào giảm tỉ lệ mới mắc các biến cố huyết khối cấp tính và sự phát triển của rối loạn chức năng thất trái. Các mục tiêu này có thể đạt được bằng cách dùng thuốc (thuốc kháng tiểu cầu, statins, ức chế men chuyển/ức chế thụ thể angiotensin II) và điều chỉnh lối sống: (i) giảm tiến triển xơ vữa động mạch; (ii) ổn định mảng xơ vữa bằng cách giảm viêm và (iii) phòng ngừa huyết khối, ngăn chặn nứt vỡ hoặc xói mòn mảng xơ vữa.

Điều trị nội khoa tối ưu là can thiệp nền tảng, hiệu quả mạnh nhưng chỉ 29% bệnh nhân trong thử nghiệm SYNTAX (Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With Taxus and Cardiac Surgery) [77] được điều trị nội khoa tối ưu ban đầu; 35% đến 40% bệnh nhân được điều trị nội khoa tối ưu sau tái thông mạch vành. Các bệnh nhân được điều trị nội khoa tối ưu giảm 36% nguy cơ tương đối tử vong trong 5 năm (HR: 0,64; KTC 95%: 0,48-0,85 [P = 0,0002]).

Mặc dù thiếu chứng cứ cải thiện các kết cục lâm sàng ở bệnh nhân bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định, CTMVQD có vai trò không thể phủ nhận ở những bệnh nhân hội chứng mạch vành cấp, hẹp nặng thân chung động mạch vành trái và một số bệnh nhân chọn lọc.

KẾT LUẬN

Nhiều thử nghiệm lâm sàng đã xác định không có chứng cứ rằng chiến lược tái thông mạch vành (can thiệp mạch vành qua da hoặc phẫu thuật bắc cầu mạch vành) phối hợp với điều trị nội khoa tối ưu cải thiện các kết cục tim mạch ở bệnh nhân bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định so với điều trị nội khoa tối ưu đơn thuần. Hơn nữa, nhiều phân tích cũng thất bại trong việc nhận diện các phân nhóm nguy cơ cao có lợi từ chiến lược CTMVQD ban đầu. Nghiên cứu ORBITA cho thấy CTMVQD không cải thiện triệu chứng đau thắt ngực so với điều trị nội khoa tối ưu. Mô hình sinh lý bệnh trong đó hẹp động mạch vành là trung tâm không còn phù hợp trong kỷ nguyên mới của y học, thay vào đó là mô hình đa yếu tố với rối loạn chức năng vi mạch, rối loạn chức năng nội mô, co thắt mạch vành, viêm, rối loạn đông máu và tiểu cầu. Điều trị nội khoa luôn là điều trị nền tảng, giữ vai trò cốt lõi và quan trọng ở bệnh nhân bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định. Chiến lược điều trị đó bao gồm giảm đau thắt ngực với các thuốc được chọn lựa dựa vào bệnh đồng mắc, đặc điểm lâm sàng và sinh lý bệnh; và phòng ngừa các biến cố tim mạch. Trong thực hành lâm sàng hàng ngày, các bác sĩ cần nhận thức, sử dụng tích cực và hiệu quả những công cụ điều trị nội khoa đó cho các bệnh nhân bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định.

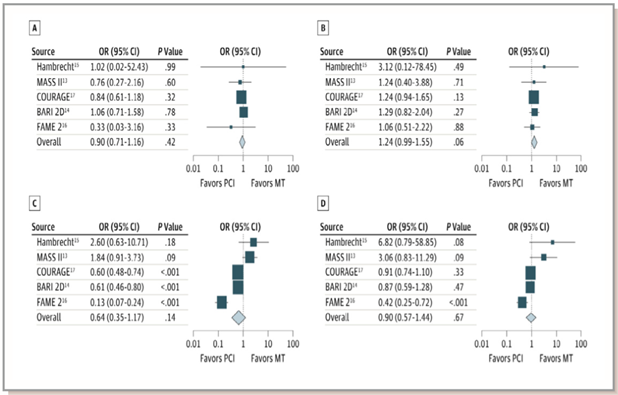

Hình 1. Các thử nghiệm so sánh can thiệp mạch vành qua da (PCI) và điều trị nội khoa (MT) về sống còn (A) và nhồi máu cơ tim không tử vong (B). (Chụp từ tài liệu gốc) [78].

Hình 2. Tỉ lệ bệnh nhân đau thắt ngực theo thời gian trong nghiên cứu COURAGE. Sự khác biệt giữa nhóm can thiệp mạch vành qua da (PCI) cộng điều trị nội khoa tối ưu (OMT) so với nhóm điều trị nội khoa tối ưu đơn thuần không có ý nghĩa thống kê. (Chụp từ tài liệu gốc) [78]

Hình 3. So sánh can thiệp mạch vành qua da (PCI) và điều trị nội khoa (MT) so với điều trị nội khoa đơn thuần ở bệnh nhân có thiếu máu cục bộ cơ tim. A: tử vong; B: nhồi máu cơ tim không tử vong; C: tái thông mạch vành khẩn; D: đau thắt ngực. (Chụp từ tài liệu gốc) [78]

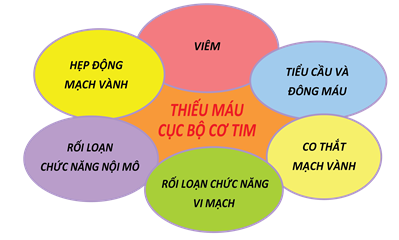

Hình 4. Mô hình sinh lý bệnh đương đại của bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định [75] (“thái dương hệ”của bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ đặt thiếu máu cục bộ cơ tim ở trung tâm của tiếp cận và hẹp động mạch vành là một trong các nguyên nhân của thiếu máu cục bộ cơ tim)

Hình 5. Phối hợp các thuốc chống đau thắt ngực dựa theo bệnh đồng mắc (Chụp từ tài liệu gốc) [79].BB: ức chế beta; DHP: ức chế canxi dihydropyridine; DILT: diltiazem; IVAB: ivabradine; NIC: nicorandil; NITR: nitrat; Non Sel-BB: ức chế beta không chọn lọc; RAN: ranolazine; Sel-BB: ức chế chọn lọc β1; TRIM: trimetazidine; VER: verapamil.

Hình 6. Phối hợp các thuốc chống đau thắt ngực dựa theo bệnh đồng mắc (Chụp từ tài liệu gốc) [79].BB: ức chế beta; DHP: ức chế canxi dihydropyridine; DILT: diltiazem; IVAB: ivabradine; NIC: nicorandil; NITR: nitrat; Non Sel-BB: ức chế beta không chọn lọc; RAN: ranolazine; Sel-BB: ức chế chọn lọc β1; TRIM: trimetazidine; VER: verapamil.

Bảng 1. Nguyên nhân của bệnh động mạch vành/bệnh tim thiếu máu cục bộ ổn định [78]

|

Vị trí tổn thương |

Cơ chế sinh lý bệnh |

Một số nguyên nhân |

|

Động mạch vành thượng tâm mạc |

Hẹp giới hạn lưu lượng |

Xơ vữa động mạch |

|

Rối loạn chức năng nội mô |

Xơ vữa động mạch, siêu vi |

|

|

Co thắt |

Xơ vữa động mạch, cocaine |

|

|

Cầu cơ |

|

|

|

Nguồn gốc bất thường |

|

|

|

Bóc tách |

Thai kỳ, chấn thương, hội chứng Marfan |

|

|

Viêm |

Ghép tim, bệnh collagen |

|

|

Vi mạch mành |

Rối loạn chức năng vi mạch |

Xơ vữa động mạch |

|

Rối loạn chức năng nội mô |

Xơ vữa động mạch |

|

|

Co thắt |

Xơ vữa động mạch |

|

|

Viêm |

Ghép tim, bệnh collagen |

|

|

Vi thuyên tắc |

Xơ vữa động mạch, rung nhĩ |

|

|

Suy mao mạch |

Phì đại thất trái |

|

|

Động mạch không phải động mạch vành |

Tăng độ cứng (tăng hậu tải) |

Vôi hóa, lão hóa, tăng huyết áp, bệnh thận mạn |

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

1. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:e44–e164.

2. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949–3003.

3. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603.

4. Dehmer GJ, Weaver D, Roe MT, et al. A contemporary view of diagnostic cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: a report from the CathPCI Registry of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, 2010 through June 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2017–2031.

5. Parisi AF, Folland ED, Hartigan P. A comparison of angioplasty with medical therapy in the treatment of single-vessel coronary artery disease. Veterans Affairs ACME Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:10–16.

6. Hueb WA, Bellotti G, de Oliveira SA, et al. The Medicine, Angioplasty or Surgery Study (MASS): a prospective, randomized trial of medical therapy, balloon angioplasty or bypass surgery for single proximal left anterior descending artery stenoses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1600–1605.

7. Coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for angina: the second Randomised Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-2) trial. RITA-2 trial participants. Lancet. 1997;350:461–468.

8. Folland ED, Hartigan PM, Parisi AF. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for stable angina pectoris: outcomes for patients with double-vessel versus single-vessel coronary artery disease in a Veterans Affairs Cooperative randomized trial. Veterans Affairs ACME InvestigatorS. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1505–1511.

9. Pitt B, Waters D, Brown WV, et al. Aggressive lipid-lowering therapy compared with angioplasty in stable coronary artery disease. Atorvastatin versus Revascularization Treatment Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:70–76.

10. Bech GJ, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional ?ow reserve to determine the appropriateness of angioplasty in moderate coronary stenosis: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2001;103:2928–2934.

11. Hueb W, Soares PR, Gersh BJ, et al. The Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS-II): a randomized, controlled clinical trial of three therapeutic strategies for multivessel coronary artery disease: one-year results. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1743–1751.

12. Boden WE, ORourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–1516.

13. Hambrecht R, Walther C, Mobius-Winkler S, et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise training in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2004;109:1371–1378.

14. Nishigaki K, Yamazaki T, Kitabatake A, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention plus medical therapy reduces the incidence of acute coronary syndrome more effectively than initial medical therapy only among patients with low-risk coronary artery disease a randomized,comparative, multicenter study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:469–479.

15. Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM, et al. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2503–2515.

16. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional ?ow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991–1001.

17. Stergiopoulos K, Brown DL. Initial coronary stent implantation with medical therapy vs medical therapy alone for stable coronary artery disease: metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:312–319.

18. Stergiopoulos K, Boden WE, Hartigan P, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes in patients with stable obstructive coronary artery disease and myocardial ischemia: a collaborative meta-analysis of contemporary randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:232–240.

19. Borden WB, Redberg RF, Mushlin AI, et al. Patterns and intensity of medical therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;305:1882–1889.

20. Lin GA, Dudley RA, Redberg RF. Cardiologists use of percutaneous coronary interventions for stable coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1604–1609.

21. Keele KD. Leonardo da Vincis views on arteriosclerosis. Med Hist. 1973;17:304–308. 22. Harvey W. Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus. Spring?eld, IL: Thomas; 1928.

23. Chirac P. Petri Chirac Consiliarii Medici et Professoris. De Motu Cordis: Adversaria Analytica. Montpellier: Apud Joannem Martel; 1698.

24. Osler W. Lectures on Angina Pectoris and Allied States. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company; 1897.

25. Klig?eld P. The early pathophysiolic understanding of angina pectoris (Edward Jenner, Caleb Hillier Parry, Alan Burns). Am J Cardiol. 1982;50:1433–1435.

26. Feil H, Siegel M. Electrocardiographic changes during attacks of angina pectoris. Am J Med Sci. 1928;175:255–269.

27. Blumgart HL, Schlesinger MJ, Zoll PM. Angina pectoris, coronary failure and acute myocardial infarction: the role of coronary occlusions and collateral circulation. JAMA. 1941;116:91–97.

28. Ryan TJ. The coronary angiogram and its seminal contributions to cardiovascular medicine over ?ve decades. Circulation. 2002;106:752–756.

29. Jones WB, Riley CP, Reeves TJ, Shef?eld LT. Natural history of coronary artery disease. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1972;48:1109–1125.

30. Robb GP, Marks HH, Mattingly TW. The value of the double standard two-step exercise test in the detection of coronary disease; a clinical and statistical follow-up study of military personnel and insurance applicants. Trans Assoc Life Insur Med Dir Am. 1956;40:52–80; discussion, 80–85.

31. Hultgren H, Calciano A, Platt F, Abrams H. A clinical evaluation of coronary arteriography. Am J Med. 1967;42:228–247.

32. Konstantinov IE. Robert H. Goetz: the surgeon who performed the ?rst successful clinical coronary artery bypass operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:1966–1972.

33. Gruntzig A. Transluminal dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis. Lancet. 1978;1:263.

34. Relman AS. The new medical-industrial complex. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:963– 970.

35. Braunwald E. Coronary-artery surgery at the crossroads. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:661–663. 36. McIntosh HD. Bene?ts from aortocoronary bypass graft. JAMA. 1978;239:1197–1199.

37. Hartigan PM, Giacomini JC, Folland ED, Parisi AF. Two- to three-year follow-up of patients with single-vessel coronary artery disease randomized to PTCA or medical therapy (results of a VA cooperative study). Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program ACME Investigators. Angioplasty Compared to Medicine. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1445–1450.

38. Hueb WA, Soares PR, Almeida De Oliveira S, et al. Five-year follow-up of the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS): a prospective, randomized trial of medical therapy, balloon angioplasty, or bypass surgery for single proximal left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis. Circulation. 1999;100:Ii107–Ii113

39. Henderson RA, Pocock SJ, Clayton TC, et al. Seven-year outcome in the RITA-2 trial: coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1161–1170.

40. Pijls NH, van Schaardenburgh P, Manoharan G, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention of functionally nonsigni?cant stenosis: 5-year follow-up of the DEFER Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2105–2111.

41. Hueb W, Lopes N, Gersh BJ, et al. Ten-year follow-up survival of the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS II): a randomized controlled clinical trial of 3 therapeutic strategies for multivessel coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122:949–957.

42. De Bruyne B, Fearon WF, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional ?ow reserve-guided PCI for stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1208–1217.

43. Sedlis SP, Hartigan PM, Teo KK, et al. Effect of PCI on long-term survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1937–1946.

44. Dagenais GR, Lu J, Faxon DP, et al. Effects of optimal medical treatment with or without coronary revascularization on angina and subsequent revascularizations in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stable ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2011;123:1492–1500.

45. Weintraub WS, Spertus JA, Kolm P, et al. Effect of PCI on quality of life in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:677–687.

46. Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi H-M, et al on behalf of the ORBITA Investigators. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial Lancet 2017. published online Nov 2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32714-9

47. Brooks MM, Chaitman BR, Nesto RW, et al. Clinical and angiographic risk strati?cation and differential impact on treatment outcomes in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial. Circulation. 2012;126:2115–2124.

48. Mancini GB, Bates ER, Maron DJ, et al. Quantitative results of baseline angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention in the COURAGE trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:320–327.

49. Mancini GB, Hartigan PM, Bates ER, et al. Prognostic importance of coronary anatomy and left ventricular ejection fraction despite optimal therapy: assessment of residual risk in the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive DruG Evaluation Trial. Am Heart J. 2013;166:481–487.

50. Maron DJ, Spertus JA, Mancini GB, et al. Impact of an initial strategy of medical therapy without percutaneous coronary intervention in high-risk patients from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive DruG Evaluation (COURAGE) trial. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1055–1062.

51. Teo KK, Sedlis SP, Boden WE, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention in older patients with stable coronary disease: a prespeci?ed subset analysis of the COURAGE (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive druG Evaluation) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1303–1308.

52. Sedlis SP, Jurkovitz CT, Hartigan PM, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with stable coronary artery disease and chronic kidney disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1647–1653.

53. McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2795–2804.

54. McNeer JF, Margolis JR, Lee KL, et al. The role of the exercise test in the evaluation of patients for ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1978;57:64–70.

55. Pijls NH, Sels JW. Functional measurement of coronary stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1045–1057.

56. Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, ?ecainide, or placebo. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:781–788.

57. Weiner DA, Ryan TJ, McCabe CH, et al. The role of exercise testing in identifying patients with improved survival after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:741–748.

58. Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival bene?t associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900–2907.

59. Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117:1283–1291.

60. Shaw LJ, Weintraub WS, Maron DJ, et al. Baseline stress myocardial perfusion imaging results and outcomes in patients with stable ischemic heart disease randomized to optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2012;164:243–250.

61. Diaz-Zamudio M, Dey D, Schuhbaeck A, et al. Automated quantitative plaque burden from coronary CT angiography noninvasively predicts hemodynamic signi?cance by using fractional ?ow reserve in intermediate coronary lesions. Radiology. 2015;276:408–415.

62. Mancini GB, Hartigan PM, Shaw LJ, et al. Predicting outcome in the COURAGE trial (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation): coronary anatomy versus ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:195–201.

63. Gould KL, Johnson NP, Bateman TM, et al. Anatomic versus physiologic assessment of coronary artery disease. Role of coronary ?ow reserve, fractional ?ow reserve, and positron emission tomography imaging in revascularization decisionmaking. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1639–1653.

64. Pijls NH, De Bruyne B, Peels K, et al. Measurement of fractional ?ow reserve to assess the functional severity of coronary-artery stenoses. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1703–1708.

65. Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional ?ow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–224.

66. Rioufol G, Mewton N, Rabilloud M, et al. The FUnctional Testing Underlying Coronary REvascularization (FUTURE) Study: A “Real World” Comparison of Fractional Flow Reserve-guided Management versus Conventional Management in Multi Vessel Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Paper presented at: American Heart Association Scienti?c Sessions 2016; November 12–16, 2016; New Orleans, LA.

67. Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1393–1399.

68. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44–e122.

69. Weintraub WS, Boden WE, Zhang Z, et al. Cost-effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention in optimally treated stable coronary patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:12–20.

70. Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, et al. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:886–895.

71. Bigi R, Cortigiani L, Bax JJ, et al. Stress echocardiography for risk strati?cation of patients with chest pain and normal or slightly narrowed coronary arteries. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:1285–1289.

72. Sicari R, Palinkas A, Pasanisi EG, Venneri L, Picano E. Long-term survival of patients with chest pain syndrome and angiographically normal or near-normal coronary arteries: the additional prognostic value of dipyridamole echocardiography test (DET). Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2136–2141.

73. Kuhn TS. The Structure of Scienti?c Revolutions (50th Anniversary Edition). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 2012.

74. Pepine CJ, Douglas PS. Rethinking stable ischemic heart disease: is this the beginning of a new era? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:957–959.

75. Marzilli M, Merz CN, Boden WE, et al. Obstructive coronary atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease: an elusive link! J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:951–956.

76. Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Walsh MN, Fleg JL. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA): developing evidence-based therapies and research agenda for the next decade. Circulation. 2017;135:1075–1092.

77. Iqbal J, Zhang YJ, Holmes DR, et al. Optimal medical therapy improves clinical outcomes in patients undergoing revascularization with percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting: insights from the Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) trial at the 5-year follow-up. Circulation. 2015;131:1269–1277.

78. Mitchell JD, Brown DL. Harmonizing the Paradigm With the Data in Stable Coronary Artery Disease: A Review and Viewpoint. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e007006 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007006.

79. Ferrari R, et al. Expert consensus document: A ‘diamond’ approach to personalized treatment of angina. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 15,120–132 (2018).