TS. BS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

7. Đánh giá chẩn đoán, quản lý và phân tầng nguy cơ theo biểu hiện lâm sàng và bệnh đã biết (có khả năng xảy ra)

7.1. Bệnh tim cấu trúc chuyên biệt

7.1.1. Bệnh động mạch vành

7.1.1.1. Hội chứng mạch vành cấp tính và co thắt mạch

7.1.1.1.1. Hội chứng mạch vành cấp tính.

SCD là nguyên nhân chính gây tử vong trong ACS, chủ yếu do rối loạn nhịp nhanh thất (VA) dai dẳng gây ra, đặc biệt là rung thất (VF). Phần lớn các nghiên cứu đã báo cáo về bệnh nhân STEMI. Trong số những bệnh nhân STEMI, 4–12% phát triển VA trong vòng 48 giờ đầu tiên sau khi xuất hiện các triệu chứng. [69,543,544] VA trước tái tưới máu phổ biến hơn rối loạn nhịp tim do tái tưới máu hoặc sau tái tưới máu trong STEMI. [545] Huyết động không ổn định, sốc tim, LVEF < 40% và tổng độ chênh của đoạn ST trong tất cả các chuyển đạo là những yếu tố dự báo độc lập của VA cả trong STEMI và không phải STEMI. [69,546] Ngoài ra, mô hình tái cực sớm có liên quan đến việc tăng nguy cơ VA và SCD trong ACS. [547]

Ngăn ngừa rồi loạn nhịp thất (VA) trong nhồi máu cơ tim ST chênh lên

Tái tưới máu khẩn cấp là liệu pháp quan trọng nhất, [292,548] vì thiếu máu cục bộ cấp tính gây ra rối loạn nhịp tim. Điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn beta cũng được khuyến nghị để ngăn ngừa VA. [3,549] Trong một thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên gần đây trên bệnh nhân STEMI, metoprolol tiêm tĩnh mạch sớm trước khi can thiệp mạch vành qua da làm giảm tỷ lệ rối loạn nhịp tim trong giai đoạn cấp tính và không liên quan đến sự gia tăng các biến cố bất lợi. [550] Điều trị dự phòng bằng AADs chưa được chứng minh là có lợi, thậm chí có thể gây hại. [322] Việc điều chỉnh sự mất cân bằng điện giải được khuyến khích mạnh mẽ. [289]

Xử trí nhịp nhanh thất dai dẳng và rung thất trong hội chứng mạch vành cấp

Chuyển nhịp hoặc khử rung tim bằng điện là can thiệp được lựa chọn để chấm dứt tức thời VA ở bệnh nhân ACS (Hình 14). [205,339] VT dai dẳng tái phát, đặc biệt khi VT đa hình hoặc VF tái phát có thể cho thấy tái tưới máu không hoàn toàn hoặc tái phát thiếu máu cục bộ cấp tính. Trong trường hợp này, chụp động mạch vành ngay lập tức được chỉ định. [3] Đối với PVT tái phát thoái hóa thành VF, nên dùng thuốc chẹn beta. [551,552] Ngoài ra, thuốc an thần sâu có thể hữu ích để giảm các cơn VT hoặc VF. [553] Amiodarone tiêm tĩnh mạch nên được xem xét để ức chế cấp thời các VA liên quan đến huyết động tái phát, mặc dù có rất ít nghiên cứu có kiểm soát đối với amiodarone trong STEMI [554] và bằng chứng trong bối cảnh này chủ yếu được ngoại suy từ các nghiên cứu về OHCA. [555] Nếu điều trị bằng beta -blockers và amiodarone không hiệu quả, có thể cân nhắc sử dụng lidocaine. [322] Việc sử dụng các AAD khác trong ACS không được khuyến nghị. [549,556] Ở những bệnh nhân có huyết động không ổn định với VA dai dẳng, có thể xem xét hỗ trợ tuần hoàn cơ học. [336,557] Đối với VA trong bối cảnh nhịp tim chậm tương đối hoặc liên quan đến khoảng ngừng, tạo nhịp có thể hiệu quả để ngăn ngừa khởi đầu.

Ý nghĩa tiên lượng của rối loạn nhịp thất sớm

VA sớm được định nghĩa là VT/VF xảy ra trong vòng 48 giờ sau STEMI. Trong kỷ nguyên tái thông mạch vành dựa trên can thiệp mạch vành (PCI) hiện đại, hầu hết tất cả VA xảy ra trong vòng 24 giờ đầu tiên. [558] VA sớm có liên quan đến tỷ lệ tử vong trong bệnh viện tăng gấp sáu lần, trong khi tiên lượng lâu dài dường như không bị ảnh hưởng đáng kể. [543,559,560] Trong một nghiên cứu thuần tập tiến cứu, bệnh nhân mắc VF trong giai đoạn STEMI cấp tính có tỷ lệ mắc SCD muộn thấp và rất giống nhau so với bệnh nhân không mắc VF trong suốt 5 năm theo dõi. [560] Đáng chú ý, VT đơn hình sớm có liên quan đến tỷ lệ can thiệp ICD đầy đủ cao hơn đáng kể so với VF sớm, và là một yếu tố dự báo tử vong độc lập trong quá trình theo dõi lâu dài. [561] Do đó, ý nghĩa tiên lượng của VT và VF xảy ra trong giai đoạn cấp tính của NMCT có thể khác nhau. Tác động của VA xảy ra muộn sau khi tái tưới máu (> 48 giờ) đối với SCD muộn là chưa rõ ràng.

Podolecki và cộng sự. [559] gần đây đã chứng minh rằng tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân lâu dài sau STEMI được dự đoán bởi VA xảy ra muộn sau khi tái tưới máu (> 48 giờ sau khi tái tưới máu), trong khi VA tái tưới máu sớm không ảnh hưởng đến kết quả 5 năm. Các nghiên cứu tiếp theo được yêu cầu để làm rõ tác động của VA xảy ra > 48 giờ sau STEMI đối với SCD muộn ở những bệnh nhân đương thời trải qua PCI cấp tính.

7.1.1.1.2. co thắt mạch.

Co thắt động mạch vành có thể có một vai trò quan trọng trong cơ chế bệnh sinh của VA. Tiên lượng lâu dài của bệnh nhân đau thắt ngực biến thể sống sót sau CA tồi tệ hơn so với những bệnh nhân đau thắt ngực biến thể khác. [562,563] Trong một cuộc khảo sát đa trung tâm ở châu Âu gần đây, 564 bệnh nhân VA thứ phát đe dọa tính mạng do co thắt mạch vành có nguy cơ tái phát cao, đặc biệt là khi điều trị y khoa không đủ. Mặc dù thuốc chẹn kênh canxi (CCB) có khả năng ngăn chặn các cơn, nhưng thuốc chẹn beta có thể kích hoạt VA. Vì sự can thiệp y tế và nhiều loại thuốc giãn mạch có thể không đủ bảo vệ, việc đặt ICD vẫn nên được xem xét ở những người sống sót sau SCA với chứng đau thắt ngực biến thể.

Bảng khuyến cáo 22 – Khuyến cáo điều trị rối loạn nhịp thất trong hội chứng mạch vành cấp và co thắt mạch

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Điều trị VA trong ACS | ||

| Điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn beta tiêm tĩnh mạch được chỉ định cho bệnh nhân PVT/VF tái phát trong STEMI trừ khi có chống chỉ định. [551,552] | I | B |

| Điều trị bằng amiodarone tĩnh mạch nên được xem xét cho những bệnh nhân PVT/VF tái phát trong giai đoạn cấp tính của ACS. [552,554,555] | IIa | C |

| Lidocaine tiêm tĩnh mạch có thể được xem xét để điều trị PVT/VF tái phát không đáp ứng với thuốc chẹn beta hoặc amiodarone, hoặc nếu amiodarone bị chống chỉ định trong giai đoạn cấp tính của ACS. [554] | IIb | C |

| Điều trị dự phòng bằng AAD (không phải thuốc chẹn beta) không được khuyến cáo trong ACS. [322] | III | B |

| Co thắt mạch | ||

| Ở những người sống sót sau SCA bị co thắt động mạch vành, nên cân nhắc cấy ICD. [562–564] | IIa | C |

AAD: thuốc chống loạn nhịp tim; ACS: hội chứng mạch vành cấp tính; ICD: máy khử rung tim cấy; PVT, nhịp nhanh thất đa hình; SCA, ngừng tim đột ngột; STEMI: nhồi máu cơ tim ST chênh lên; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VF: rung thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

7.1.1.2. Thời gian sớm sau nhồi máu cơ tim

Những tuần đầu tiên sau STEMI có nguy cơ tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân và SCD cao nhất, đặc biệt ở những bệnh nhân có LVEF giảm. [565,566] Vì lý do này, nên đánh giá sớm LVEF, tức là trước khi xuất viện. [567,568] Cấy ICD dự phòng sớm trong 40 ngày đầu tiên sau MI không làm giảm tỷ lệ tử vong ở bệnh nhân sau MI có LVEF giảm trong hai thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên (DINAMIT và IRIS), [569,570] và do đó không được khuyến cáo. Đánh giá sớm bằng các xét nghiệm không xâm lấn khác, ngoài phép đo LVEF, cũng không được chứng minh là hữu ích cho việc phân tầng nguy cơ liên quan đến SCD. [571] Bằng chứng hạn chế cho thấy rằng phân tầng nguy cơ xâm lấn bằng PES trong giai đoạn đầu sau MI có thể hữu ích để xác định bệnh nhân có nguy cơ cao bị giảm LVEF. [572] Tuy nhiên, tiện ích của phương pháp này cho đến nay vẫn chưa được xác nhận trong các nghiên cứu ngẫu nhiên. Thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên PROTECT-ICD (NCT03588286) hiện đang kiểm tra xem PES có thể hướng dẫn quyết định cấy ICD ở những bệnh nhân bị giảm EF trong giai đoạn đầu sau STEMI hay không.

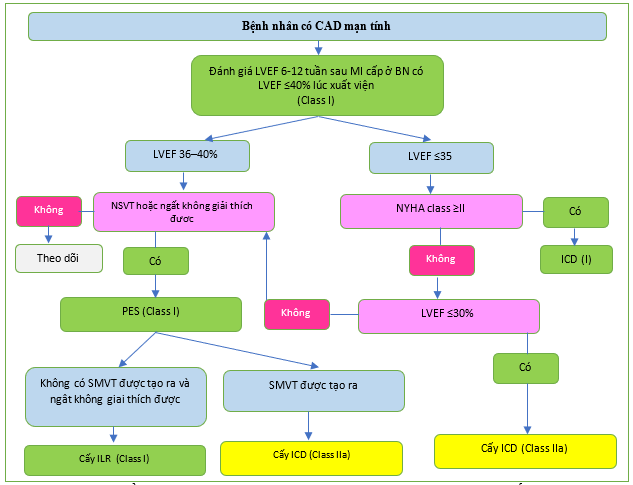

Tái cấu trúc đảo ngược sau MI có liên quan đến tỷ lệ tử vong, SCA và các kết quả lâm sàng bất lợi khác thấp hơn đáng kể. [573,574] Do đó, việc đánh giá chỉ định cấy ICD dự phòng, thường được thực hiện bằng siêu âm tim lặp lại, nên diễn ra trong giai đoạn sau tái cấu trúc NMCT sau 6 tuần đầu tiên ở bệnh nhân có LVEF trước xuất viện ≤40%. Đánh giá lại LVEF trước 6 tuần sau NMCT có thể không phân biệt được giữa cơ tim choáng váng và tái cấu trúc.

Trong giai đoạn đầu sau NMCT, cơn bão điện và/hoặc các đợt PVT hoặc VF tái phát là những tình trạng đe dọa tính mạng ngay lập tức. Trong bối cảnh này, điều quan trọng là phải loại trừ thiếu máu cục bộ là yếu tố kích hoạt rối loạn nhịp tim. Nếu điều trị nội khoa không đủ để ức chế các đợt loạn nhịp, triệt phá qua ống thông có khả năng hiệu quả đặc biệt nếu các đợt được kích hoạt cục bộ do các PVC tương tự. [332,575] Nếu PVT tái phát mặc dù đã điều trị bằng betablocker và amiodarone, thì việc ức chế bằng liệu pháp quinidine đã được báo cáo. [323]

Bảng khuyến cáo 23 — Khuyến cáo phân tầng nguy cơ và điều trị rối loạn nhịp thất sau nhồi máu cơ tim

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ | ||

| Đánh giá LVEF sớm (trước khi xuất viện) được khuyến cáo ở tất cả bệnh nhân NMCT cấp. [567,568] |

I |

B |

| Ở những bệnh nhân có LVEF trước khi xuất viện ≤40%, khuyến cáo đánh giá lại LVEF 6-12 tuần sau NMCT để đánh giá nhu cầu cấy ICD dự phòng tiên phát. [568.573.574] |

I |

C |

| Điều trị VAs | ||

| Triệt phá qua catheter nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có các đợt PVT / VF tái phát được kích hoạt PVC tương tự không đáp ứng với điều trị nội khoa hoặc tái thông mạch vành trong giai đoạn bán cấp của NMCT. [332] |

IIa |

C |

ICD: máy khử rung tim cấy; LVEF: phân suất tống máu thất trái; MI: nhồi máu cơ tim; PVC: phức hợp thất sớm; PVT: nhịp nhanh thất đa hình; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VF: rung thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

7.1.1.3. Bệnh động mạch vành mạn tính

7.1.1.3.1. Ngăn ngừa tiên phát đột tử tim ở các bệnh nhân phân suất tống máu giảm.

Bốn mươi ngày sau STEMI, khoảng 5% bệnh nhân sẽ có LVEF ≤35%. [576] Những bệnh nhân này có nguy cơ SCD. Do đó, ở những bệnh nhân có LVEF ≤ 35% và có các triệu chứng suy tim NYHA II và III, nên cấy ICD dự phòng ban đầu. [356] Cấy ICD cũng nên được xem xét cho những bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng với EF ≤30%. [354] Trong quần thể này, việc giảm tử vong do ICD đã được chứng minh trong bốn RCT. [353–356] Ở những bệnh nhân CAD, LVEF giảm (≤40%) và NSVT không triệu chứng, khả năng tạo ra bởi PES xác định những bệnh nhân được hưởng lợi từ ICD, độc lập với phân loại NYHA. [355]

Kể từ khi các thử nghiệm nói trên được công bố, các chiến lược tái thông mạch máu sớm và thuốc điều trị suy tim hiện nay đã làm giảm nguy cơ chung của SCD ở bệnh nhân suy tim. [577] Mặc dù tổng tỷ lệ tử vong đã giảm, nhưng mức giảm tương đối của ICD là 27% nhất quán, điều này đã được chứng thực trong hai nghiên cứu đăng ký tiền cứu lớn gần đây thu nhận 2327 bệnh nhân châu Âu từ năm 2014 đến 2018 (EU-CERT-ICD) [357] và 2610 bệnh nhân Thụy Điển đăng ký từ năm 2000 đến 2016 (đăng ký SwedeHF). [358]

Bảng khuyến cáo 24. — Các khuyến cáo cho phân tầng nguy cơ, dự phòng đột tử tim, và điều trị rối loạn nhịp trong bệnh mạch vành mạn

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ và ngăn ngừa SCD tiên phát | ||

| Ở bệnh nhân ngất và STEMI trước đó, PES được chỉ định khi ngất vẫn không giải thích được sau khi đánh giá không xâm lấn. [146.584] | I | C |

| Liệu pháp ICD được khuyến cáo ở bệnh nhân CAD, suy tim có triệu chứng (NYHA độ II – III), và LVEF ≤35% mặc dù đã điều trị OMT ≥ 3 tháng. [354.356] |

I |

A |

| Liệu pháp ICD nên được cân nhắc ở những bệnh nhân có CAD, NYHA loại I, và LVEF ≤30% mặc dù điều trị OMT ≥ 3 tháng. [354] | IIa | B |

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có CAD, LVEF ≤40% mặc dù OMT ≥ 3 tháng và NSVT, nếu chúng có thể gây ra SMVT bằng PES. [355] |

IIa |

B |

| Ở bệnh nhân có CAD, điều trị dự phòng bằng AADs ngoài beta-blockers không được khuyến cáo. [556,578,579] | III | A |

| Ngăn ngừa SCD thứ phát và điều trị VA | ||

| Cấy ICD được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân không bị thiếu máu cục bộ tiếp diễn với VF hoặc VT không dung nạp huyết động được ghi nhận xảy ra muộn hơn 48 giờ sau NMCT. [349–351] |

I |

A |

| Ở bệnh nhân CAD và SMVT tái phát, có triệu chứng, hoặc ICD shock đối với SMVT mặc dù đã điều trị amiodarone kéo dài, nên triệt phá qua catheter thay vì liệu pháp AAD leo thang. [471] |

I |

B |

| Việc bổ sung amiodarone đường uống hoặc thay thế thuốc chẹn bêta bằng sotalol nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh CAD với SMVT tái phát, có triệu chứng hoặc ICD shock đối với bệnh SMVT khi đang điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn bêta. [318.581] |

IIa |

B |

| Ở bệnh nhân CAD và SMVT huyết động dung nạp tốt và LVEF ≥40%, triệt phá qua catheter ở các trung tâm có kinh nghiệm nên được coi là một giải pháp thay thế cho liệu pháp ICD, miễn là đã đạt được các tiêu chí đã được thiết lập. C, [480,580] |

IIa |

C |

| Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân có SMVT dung nạp huyết động và LVEF ≥40% nếu triệt phá VT thất bại, không có sẵn hoặc không được mong muốn. |

IIa |

C |

| Triệt phá qua catheter nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân CAD và các SMVT tái phát, có triệu chứng, hoặc ICD shock đối với SMVT mặc dù đã điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn beta hoặc sotalol. [471] |

IIa |

C |

| Ở những bệnh nhân có CAD đủ điều kiện để cấy ICD, triệt phá qua catheter có thể được xem xét ngay trước (hoặc ngay sau) cấy ICD để giảm gánh nặng VT và các sốc ICD sau đó. [484.485.582.583] |

IIb |

B |

AAD: thuốc chống loạn nhịp tim; CAD: bệnh động mạch vành; ICD, máy khử rung tim cấy; LVEF, phân suất tống máu thất trái; MI, nhồi máu cơ tim; NSVT, nhịp nhanh thất tạm thời; NYHA, Hội Tim New York; OMT, điều trị nội tối ưu; PES: kích thích điện được lập trình; SCD: đột tử do tim; SMVT: nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng; STEMI: nhồi máu cơ tim ST chênh lên; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VF: rung thất; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

c Không có khả năng tạo ra VT và loại bỏ điện đồ phù hợp với sự chậm trễ dẫn truyền

7.1.1.3.2. Dự phòng đột tử do tim tiên phát ở bệnh nhân có phân suất tống máu được bảo tồn hoặc giảm nhẹ.

Không có dữ liệu hỗ trợ việc cấy ICD dự phòng tiên phát ở bệnh nhân sau nhồi máu với LVEF được bảo tồn hoặc giảm nhẹ. Những bệnh nhân này không đồng nhất về nền rối loạn nhịp tim tiềm ẩn của họ và những nỗ lực đang được tiến hành để xác định những người có nguy cơ SCD cao nhất. PES được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân sau nhồi máu có ngất vẫn không giải thích được sau khi đánh giá không xâm lấn để hướng dẫn quản lý bệnh nhân (Hình 15). [146]

Hình 15. Thuật toán phân tầng nguy cơ và dự phòng đột tử tim tiên phát ở bệnh nhân mắc bệnh động mạch vành mạn tính và phân suất tống máu giảm.

CAD: bệnh động mạch vành; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; ILR, máy ghi vi mạch có thể cấy; LVEF: phân suất tống máu thất trái; MI: nhồi máu cơ tim; N: Không; NSVT: nhịp nhanh thất tạm thời; NYHA: Hiệp hội Tim mạch New York; PES: kích thích điện được lập trình; SMVT, nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng; Yes: có. a- Hướng dẫn ESC năm 2018 về chẩn đoán và quản lý ngất.[1]

Trong nghiên cứu PRESERVE-EF, 41 trong số 575 bệnh nhân sau nhồi máu có LVEF ≥40% và một yếu tố nguy cơ điện tâm đồ không xâm lấn hơn 40 ngày sau NMCT không thể tạo ra VT/VF trong PES và đã nhận ICD. [151] Trong thời gian theo dõi 32 tháng, không có SCD nào xảy ra và 9 trong số 37 bệnh nhân ICD được điều trị bằng ICD thích hợp. Tuy nhiên, vai trò của điều trị ICD thích hợp như là phương pháp thay thế cho SCD ở bệnh nhân LVEF bảo tồn vẫn chưa được biết và cần có các thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên. Điều trị dự phòng bằng AAD không phải thuốc chẹn beta không được chỉ định bất kể LVEF. [556,578,579]

7.1.1.3.3. Ngăn ngừa đột tử tim thứ phát.

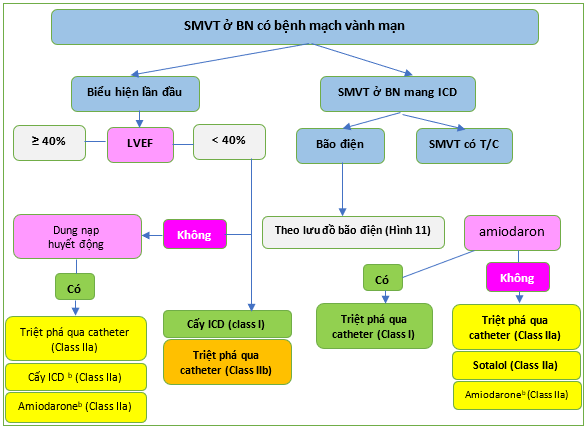

Ba thử nghiệm ICD phòng ngừa thứ phát quan trọng đã thu nhận 1866 bệnh nhân từ năm 1990 đến 1997. [349–351] Một phân tích tổng hợp ở cấp độ bệnh nhân đã chứng minh tỷ lệ tử vong giảm 28% (HR 0,72; KTC 95% 0,60–0,87; P = 0,0006) gần như hoàn toàn do giảm tử vong do loạn nhịp tim (HR 0,50; 95% CI 0,37–0,67; P , 0,0001) trong nhóm ICD. [352] Điều này có nghĩa là kéo dài thời gian sống thêm 4,4 tháng trong thời gian theo dõi trung bình 6 năm của ICD. Khoảng 80% dân số nghiên cứu bị CAD. Bệnh nhân SMVT dung nạp tốt đã bị loại khỏi các thử nghiệm phòng ngừa thứ phát (Hình 16).

Hình 16 Thuật toán quản lý nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng ở bệnh nhân mắc bệnh động mạch vành mãn tính.

CAD: bệnh động mạch vành; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LVEF: phân suất tống máu thất trái; N,: Không; SMVT: nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình dai dẳng; Yes: có. a- Nhịp nhanh thất không ngừng ở vùng theo dõi: xem xét triệt phá qua ống thông. b- Nếu không có phương pháp triệt phá qua catheter, không thành công hoặc bệnh nhân không mong muốn. c- Để giảm các cú sốc ICD.

7.1.1.3.4. Quản lý bệnh nhân nhịp nhanh thất dung nạp huyết động và phân suất tống máu bảo tồn và giảm nhẹ.

Với sự hiểu biết tốt hơn về các cơ chế của VT sau MI, cũng như các công nghệ hình ảnh và triệt phá được cải thiện, triệt phá qua catheter đã trở thành một lựa chọn để điều trị VT dung nạp tốt về mặt huyết động ở những bệnh nhân sau MI được lựa chọn với EF bảo tồn hoặc giảm nhẹ, thậm chí không có ICD dự phòng. Một thử nghiệm hồi cứu đơn trung tâm nhỏ đã nghiên cứu bệnh nhân CAD, LVEF > 40% và VT dung nạp huyết động đã trải qua triệt phá qua catheter như liệu pháp đầu tay. [580] Các nhà điều tra có thể loại bỏ 90% các VT lâm sàng và 58% tất cả các VT có thể tạo ra. Sau đó, 42% bệnh nhân được đặt ICD. Sau thời gian theo dõi trung bình là 3,8 năm, 42% bệnh nhân tử vong bất kể có hay không có ICD (P = 0,47).

Một nghiên cứu hồi cứu đa trung tâm lớn hơn đã xem xét 166 bệnh nhân có LVEF > 30% biểu hiện bằng SMVT dung nạp tốt, chỉ được điều trị bằng triệt phá qua catheter và so sánh kết quả với nhóm đối chứng gồm 378 bệnh nhân được cấy ICD. [480[ Trong số 166 bệnh nhân trải qua triệt phá như liệu pháp đầu tiên, 55% bị CAD. LVEF trung bình là 50% và sau thời gian theo dõi trung bình là 32 tháng, tỷ lệ tử vong chung không khác nhau giữa các nhóm (12%).

Những dữ liệu này gợi ý nên xem xét cấy ICD hoặc triệt phá ở các trung tâm có kinh nghiệm ở những bệnh nhân có EF bảo tồn hoặc giảm nhẹ có biểu hiện SMVT dung nạp huyết động. Đáng chú ý, mặc dù ICD thường được cấy trong quần thể này, nhưng các thử nghiệm ICD phòng ngừa thứ phát không cho thấy lợi ích sống sót ở những bệnh nhân có LVEF ≥ 35%. [352] Mặc dù SMVT hiếm gây ra do thiếu máu cục bộ và tái thông mạch máu đơn thuần không ngăn ngừa VT tái phát, việc loại trừ hoặc điều trị CAD đáng kể trước khi triệt phá qua catheter là hợp lý.

7.1.1.3.5. Quản lý nhịp nhanh thất tái phát trong người mang máy khử rung tim.

VT thường xuyên, có triệu chứng ở người đã được cấy ICD nên được điều trị thuốc bằng amiodarone hoặc sotalol. [318,581] Ở những bệnh nhân CAD mà SMVT tái phát trong khi điều trị bằng amiodarone, nên triệt phá qua catheter thay vì leo thang điều trị AAD. Trong thử nghiệm VANISH, tiêu chí kết hợp tổng hợp về tử vong, cơn bão VT và liệu pháp ICD thích hợp đạt được ít thường xuyên hơn ở nhóm triệt phá so với nhóm điều trị bằng amiodarone tăng dần trong thời gian theo dõi trung bình là 28 tháng (59% so với . 68,5%; HR 0,72; KTC 95% 0,53– 0,98; P = 0,04). [471] Thử nghiệm VANISH2 đang diễn ra (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT 02830360) giải quyết câu hỏi liệu phương pháp điều trị đầu tay bằng phương pháp triệt phá qua catheter có vượt trội hơn so với liệu pháp AAD ở bệnh nhân SMVT sau MI hay không.

Triệt phá VT dự phòng sau SMVT đầu tiên được ghi nhận, sau đó là cấy ICD, không làm giảm tỷ lệ tử vong cũng như nhập viện vì rối loạn nhịp tim hoặc suy tim nặng hơn khi so sánh với chiến lược triệt phá trì hoãn chỉ sau cú sốc ICD thứ ba. [582]

Tuy nhiên, ở những bệnh nhân có đợt VT đầu tiên và ở những người được chỉ định ICD, việc triệt phá qua catheter được thực hiện ngay trước hoặc ngay sau khi cấy ICD có thể được xem xét để giảm các VT và các sốc ICD tiếp theo. [484,485,583]

7.1.1.4. Các bất thường động mạch vành

Nguồn gốc động mạch vành ở mạch chủ bất thường, bên trái hoặc bên phải, phát sinh từ xoang Valsalva đối diện, có liên quan đến việc tăng nguy cơ SCD, đặc biệt ở những người trên 35 tuổi trong hoặc sau khi gắng sức mạnh. [585] Nguồn gốc động mạch chủ bất thường của động mạch vành trái ít phổ biến hơn nhưng ác tính hơn so với nguồn gốc động mạch chủ bất thường của động mạch vành phải. Các yếu tố nguy cơ khác đối với SCD là đường đi giữa động mạch giữa động mạch chủ và động mạch phổi, lỗ thông có hình giống như khe, lỗ thông cao, góc nhọn, đường đi trong thành và chiều dài của nó. [585,586] Chỉ định can thiệp phẫu thuật, đặc biệt ở những bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng, dựa trên đánh giá giải phẫu nguy cơ cao bằng CTA và đánh giá thiếu máu cục bộ do gắng sức bằng các phương thức chẩn đoán hình ảnh tiên tiến. [586–588] Hình ảnh tim gắng sức cũng được chỉ định để đánh giá gắng sức thiếu máu cục bộ sau can thiệp phẫu thuật, đặc biệt ở bệnh nhân CA được cứu sống. [588]

Bảng khuyến cáo 25 — Khuyến cáo ngăn ngừa đột tử tim ở các bệnh nhân bất thường động mạch vành

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Đánh giá chẩn đoán | ||

| Hình ảnh tim gắng sức trong khi gắng sức thể lực được khuyến nghị bổ sung cho test gắng sức tim phổi ở những bệnh nhân có nguồn gốc động mạch chủ bất thường của động mạch vành với đường đi giữa các động mạch để xác nhận/loại trừ thiếu máu cục bộ cơ tim. [587] |

I |

C |

| Hình ảnh gắng sức tim trong khi gắng sức thể lực được khuyến cáo cùng với test gắng sức tim phổi sau phẫu thuật ở những bệnh nhân có nguồn gốc động mạch chủ bất thường của động mạch vành có tiền sử CA được cứu sống. |

I |

C |

| Điều trị | ||

| Phẫu thuật được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân có nguồn gốc động mạch vành bất thường với CA, ngất nghi ngờ do VA, hoặc đau thắt ngực khi các nguyên nhân khác đã được loại trừ. [585,586,588] |

I |

C |

| Phẫu thuật nên được cân nhắc ở những bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng có nguồn gốc động mạch vành bất thường và có bằng chứng thiếu máu cục bộ cơ tim hoặc nguồn gốc động mạch chủ bất thường của động mạch vành trái với giải phẫu nguy cơ cao.c, [585,586,588] |

IIa |

C |

CA: ngừng tim; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

c Giải phẫu nguy cơ cao được định nghĩa khi đường đi trong động mạch, lỗ thông được định hình giống như khe, góc gập đột ngột, và đường đi và chiều dài của nó trong cơ.

7.1.2. Phức hợp thất sớm nguyên phát/nhịp nhanh thất và bệnh cơ tim do phức hợp thất sớm

7.1.2.1. Phức hợp thất sớm nguyên phát/nhịp nhanh thất

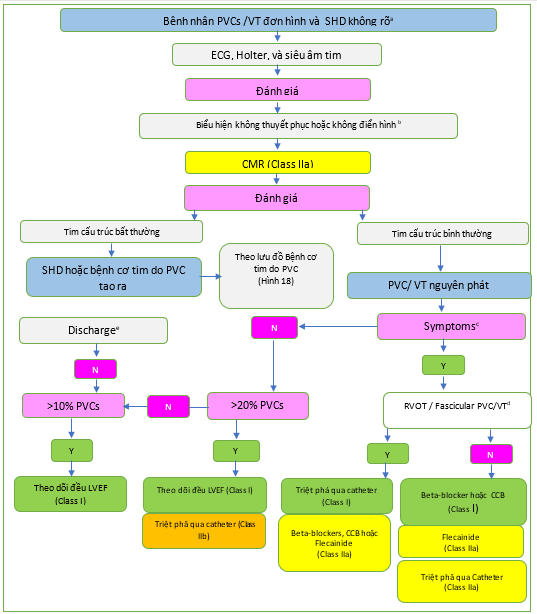

PVCs/VT ở bệnh nhân không có SHD được định nghĩa là nguyên phát (Hình 17). Ở những bệnh nhân được cho là PVCs/VT nguyên phát dựa trên tiền sử âm tính và khám thực thể bình thường, ECG 12 chuyển đạo và siêu âm tim qua thành ngực là những bước chẩn đoán đầu tiên quan trọng để loại trừ SHD tiềm ẩn. Theo dõi ECG Holter 24 giờ thường được thực hiện để xác định gánh nặng PVC. PVC đa dạng khi theo dõi điện tâm đồ kéo dài và những thay đổi nhỏ trên điện tâm đồ hoặc siêu âm tim cần phải được công nhận. [589] CMR nên được thực hiện bất cứ khi nào điện tâm đồ và siêu âm tim không thể kết luận để loại trừ SHD, hoặc biểu hiện lâm sàng làm tăng nghi ngờ về SHD.[590,591]

Bệnh nhân cần được điều trị khi PVCs/VT có triệu chứng hoặc liên quan đến suy giảm chức năng tim. Quá trình lâm sàng và đáp ứng với các phương pháp điều trị khác nhau hầu hết đã được nghiên cứu ở những rồi loạn nhịp bắt nguồn từ RVOT hoặc bó trái.

Một số loại thuốc đã được sử dụng để điều trị PVCs/VT nguyên phát. Khuyến cáo dựa trên các nghiên cứu chuỗi nhỏ hoặc không có đối chứng. Thuốc chẹn beta và chẹn kênh canxi là những loại thuốc được nghiên cứu nhiều nhất và cả hai đều được chứng minh là có hiệu quả trong việc ức chế rối loạn nhịp tim. [304] Bằng chứng về flecainide là khan hiếm. [592] Trong trường hợp gánh nặng PVC cao hơn với nhịp tim cao hơn hoặc trong khi gắng sức, thuốc chẹn beta nên được ưu tiên.[593] Nếu không có mối tương quan như vậy, việc sử dụng thuốc flecainide hoặc CCB có liên quan đến việc ức chế PVC hiệu quả hơn. Thuốc chẹn beta cũng nên được chọn khi nghi ngờ có cơ chế ổ hoạt động khởi kích. CCB nên là thuốc được lựa chọn cho PVC/VT bó. Mặc dù thiếu dữ liệu, beta blockers hoặc CCB được coi là lựa chọn đầu tiên cho PVC có nguồn gốc bên ngoài RVOT hoặc bó trái vì flecainide có thể có tác dụng phụ gây loạn nhịp tim. Amiodarone có liên quan đến độc tính toàn thân nghiêm trọng và chỉ nên được sử dụng nếu triệt phá hoặc các loại thuốc khác không thành công hoặc không thể sử dụng được. [594] Một bản tóm tắt các khuyến cáo để điều trị PVCs/VT nguyên phát và bệnh cơ tim do PVC gây ra hoặc làm trầm trọng thêm với AAD được cung cấp trong Bảng 9.

Tỷ lệ thành công cao của triệt phá PVCs/VT nguyên phát qua catheter đã được báo cáo với các biến chứng hiếm gặp, đặc biệt đối với RVOT và các type bó. [535] Trong một nghiên cứu ngẫu nhiên gồm các bệnh nhân RVOT PVC, triệt phá vượt trội so với liệu pháp AAD trong việc ức chế rối loạn nhịp tim mà không có sự khác biệt về biến chứng. [595] Do đó, triệt phá được khuyến cáo là liệu pháp đầu tay cho RVOT và PVCs/VT bó. Thông tin sẵn có cho các dạng PVCs/VT nguyên phát khác bị hạn chế và chủ yếu chỉ giới hạn ở mức độ thành công cấp tính của quá trình triệt phá, nói chung, thấp hơn và liên quan đến tái phát nhiều hơn so với RVOT và PVCs/VT bó. [540] Ngoài ra, việc tiếp cận và triệt phá tại các vị trí đặc biệt (ví dụ: xoang Valsalva, đỉnh LV) có thể làm tăng nguy cơ biến chứng thủ thuật. Do đó, khi ECG 12 chuyển đạo rất nghi ngờ về nguồn PVC/VT bên ngoài RVOT hoặc bó trái, mức độ khuyến cáo cho việc triệt phá sẽ thấp hơn.

Bảng 9. Tóm tắt các khuyến cáo điều trị bệnh nhân thường xuyên có phức hợp thất sớm nguyên phát / nhịp nhanh thất hoặc bệnh cơ tim do phức hợp thất sớm

| Triệt phá | Beta-blocker | CCB | Flecainide | Amiodarone | |

| RVOT/PVC/VT bó: Có triệu chứng, chức năng LV bình thường | Class I | Class IIa | Class IIa | Class IIa | Class III |

| TPVC/VT không phải RVOT/bó: Có triệu chứng, chức năng LV bình thường | Class IIa | Class I | Class I | Class IIa | Class III |

| RVOT/PVC bó/VT: Rối loạn chức năng LV | Class I | Class IIa | Class IIIa | Class IIab | Class IIa |

| PVC/VT không phải RVOT/bó: Rối loạn chức năng LV | Class I | Class IIa | Class IIIa | Class IIab | Class IIa |

| PVC:

Gánh nặng > 20%, Không triệu chứng, chức năng LV bình thường |

Class IIb | Class III |

CCB: thuốc chẹn kênh canxi; LV: thất trái; PVC: phức hợp thất sớm; RVOT: đường ra thất phải; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

a.Thuốc chẹn kênh canxi tiêm tĩnh mạch.

b Ở một số bệnh nhân được chọn (chỉ rối loạn chức năng LV trung bình).

Hình 17. Quy trình quản lý bệnh nhân có phức hợp thất sớm nguyên phát/nhịp nhanh thất và bệnh tim cấu trúc không rõ ràng.

CCB: thuốc chẹn kênh canxi; CMR: cộng hưởng từ tim; ECG: điện tâm đồ; LVEF: phân suất tống máu thất trái; N: Không; PVC: phức hợp tâm thất sớm; RVOT: đường ra thất phải; SHD: bệnh tim cấu trúc; VT: nhịp nhanh thất; Y: có.

a- SHD không rõ đang được xác định là do không có bất thường đáng kể nào khi khám thực thể, điện tâm đồ cơ bản và siêu âm tim. b- Biểu hiện không điển hình: ví dụ lớn tuổi, hình thái block nhánh phải, VT đơn hình dai dẳng phù hợp với vào lại. c- Các triệu chứng phải phù hợp và liên quan đến PVC/VT. d- Nguồn gốc bị nghi ngờ bằng ECG hoặc được xác nhận trong quá trình đánh giá điện sinh lý. e- Xem xét đánh giá lại trong trường hợp có các triệu chứng mới hoặc thay đổi về tình trạng lâm sàng của bệnh nhân.

(Còn nữa)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

- Pedersen CT, Kay GN, Kalman J, Borggrefe M, Della-Bella P, Dickfeld T, et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS expert consensus on ventricular arrhythmias. Europace 2014; 16:1257–1283.

- Cronin EM, Bogun FM, Maury P,Peich lP, Chen M, Namboodiri N, etal.2019HRS/ EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus statement on catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias. Europace 2019; 21:1143–1144.

- Kowlgi GN, Cha Y-M. Management of ventricular electrical storm: a contemporary appraisal. Europace 2020; 22:1768–1780.

- Guerra F, Shkoza M, Scappini L, Flori M, Capucci A. Role of electrical storm as a mortality and morbidity risk factor and its clinical predictors: a meta-analysis. Europace 2014; 16:347–353.

- Noda T, Kurita T, Nitta T, Chiba Y, Furushima H, Matsumoto N, et al. Significant impact of electrical storm on mortality in patients with structural heart disease and an implantable cardiac defibrillator. Int J Cardiol 2018; 255:85–91.

- Soar J, Maconochie I, Wyckoff MH, Olasveengen TM, Singletary EM, Greif R, et al. 2019 International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations: summary from the basic life support; advanced life support; pediatric life support; neonatal life support; education, implementation, and teams; and first aid task forces. Circulation 2019;140: e826–e880.

- Eifling M, Razavi M, Massumi A. The evaluation and management of electrical storm. Tex Heart Inst J 2011;38: 111–121.

- Chatzidou S, Kontogiannis C, Tsilimigras DI, Georgiopoulos G, Kosmopoulos M, Papadopoulou E, et al. Propranolol versus metoprolol for treatment of electrical storm in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71:1897–1906.

- Connolly SJ, Dorian P, Roberts RS, Gent M, Bailin S, Fain ES, et al. Comparison of beta-blockers, amiodarone plus beta-blockers, or sotalol for prevention of shocks from implantable cardioverter defibrillators: the OPTIC Study: a randomized trial. JAMA 2006; 295:165–171.

- Shiga T, Ikeda T, Shimizu W, Kinugawa K, Sakamoto A, Nagai R, et al. Efficacy and safetyoflandiololinpatientswithventriculartachyarrhythmiaswithorwithoutrenal impairment – subanalysis of the J-Land II study. Circ Rep 2020; 2:440–445.

- Kanamori K, Aoyagi T, Mikamo T, Tsutsui K, Kunishima T, InabaH, et al. Successful treatment of refractory electrical storm with landiolol after more than 100 electrical defibrillations. Int Heart J 2015; 56: 555–557.

- Gorgels AP, van den Dool A, Hofs A, Mulleneers R, Smeets JL, Vos MA, et al. Comparisonofprocainamideandlidocaineinterminatingsustainedmonomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1996; 78:43–46.

- Martí-Carvajal AJ, Simancas-Racines D, Anand V, Bangdiwala S. Prophylactic lidocaine for myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 2015: CD008553.

- Viskin S, Chorin E, Viskin D, Hochstadt A, Halkin A, Tovia-Brodie O, et al. Quinidine-responsive polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation 2019; 139: 2304 – 2314.

- Viskin S, Hochstadt A, Chorin E, Viskin D, Havakuk O, Khoury S, et al. Quinidine-responsive out-of-hospital polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary heart disease. Europace 2020;22: 265–273.

- Martins RP, Urien J-M, Barbarot N, Rieul G, Sellal J-M, Borella L, et al. Effectiveness of deep sedation for patients with intractable electrical storm refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs. Circulation 2020;142: 1599–1601.

- Fudim M, Boortz-Marx R, Ganesh A, Waldron NH, Qadri YJ, Patel CB, etal. Stellate ganglion blockade for the treatment of refractory ventricular arrhythmias: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2017;28: 1460–1467.

- Do DH, Bradfield J, Ajijola OA, Vaseghi M, Le J, Rahman S, et al. Thoracic epidural anesthesiacanbeeffectivefortheshort-termmanagementofventriculartachycardia storm. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e007080.

- Vaseghi M, Barwad P, Malavassi Corrales FJ, Tandri H, Mathuria N, Shah R, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69: 3070 – 3080.

- Gatzoulis KA, Andrikopoulos GK, Apostolopoulos T, Sotiropoulos E, Zervopoulos G, Antoniou J, et al. Electrical storm is an independent predictor of adverse longterm outcome in the era of implantable defibrillator therapy. Europace 2005;7: 184–192.

- Carbucicchio C, Santamaria M, Trevisi N, Maccabelli G, Giraldi F, Fassini G, et al. Catheterablationforthetreatmentofelectricalstorminpatientswithimplantable cardioverter-defibrillators: short- and long-term outcomes in a prospective singlecenter study. Circulation 2008;117: 462–469.

- Vergara P, Tung R, Vaseghi M, Brombin C, Frankel DS, Di Biase L, et al. Successful ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with electrical storm reduces recurrences and improves survival. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15:48–55.

- Komatsu Y, Hocini M, Nogami A, Maury P, Peichl P, Iwasaki Y, et al. Catheter ablationofrefractoryventricular fibrillationstormaftermyocardialinfarction:amulticenter study. Circulation 2019; 139:2315–2325.

- Knecht S, Sacher F, Wright M, Hocini M, Nogami A, Arentz T, et al. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation ablation: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:522–528.

- Peich lP, Cihák R, Kozeluhová M, Wichterle D, Vancura V, Kautzner J. Catheter ablation of arrhythmic storm triggered by monomorphic ectopic beats in patients with coronary artery disease. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2010;27: 51–59.

335.LePennec-PrigentS, FlecherE, AuffretV, LeurentG, DaubertJ-C, LeclercqC,etal. Effectiveness of extracorporeal life support for patients with cardiogenic shock due to intractable arrhythmic storm. Crit Care Med 2017;45: e281–e289. 336. Mariani S, Napp LC, Lo Coco V, Delnoij TSR, Luermans JGLM, Ter Bekke RMA, et al. Mechanical circulatory support for life-threatening arrhythmia: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2020; 308:42–49.

- Muser D, Liang JJ, Castro SA, Hayashi T, Enriquez A, Troutman GS, etal. Outcomes with prophylactic use of percutaneous left ventricular assist devices in high-risk patients undergoing catheter ablation of scar-related ventricular tachycardia: a propensity-score matched analysis. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15:1500–1506.

- Mathuria N, Wu G, Rojas-Delgado F, Shuraih M, Razavi M, Civitello A, et al. Outcomesofpre-emptiveandrescueuseofpercutaneousleftventricularassistdevice in patients with structural heart disease undergoing catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2017; 48:27–34.

- Patel KK, Spertus JA, Khariton Y, Tang Y, Curtis LH, Chan PS, etal. Association between prompt defibrillation and epinephrine treatment with long-term survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2018;137: 2041–2051.

- Vaseghi M, Gima J, Kanaan C, Ajijola OA, Marmureanu A, Mahajan A, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias or electrical storm: Intermediate and long-term follow-up. Heart Rhythm 2014;11: 360–366.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task forcefor the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:2129–2200.

- Mc Donagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, etal.2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021; 42:3599–3726.

- AlJaroudi WA, Refaat MM, Habib RH, Al-Shaar L, Singh M, Gutmann R, et al. Effect ofangiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and receptor blockers on appropriate implantable cardiac defibrillator shock in patients with severe systolic heart failure (from the GRADE Multicenter Study). Am J Cardiol 2015; 115: 924–931.

- Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1309–1321.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:993–1004.

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020;383: 1413–1424.

- Desai AS, McMurray JJV, Packer M, Swedberg K, Rouleau JL, Chen F, et al. Effect of the angiotensin-receptor-neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 compared with enalapril on mode of death in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:1990–1997.

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021; 42:373–498.

- Connolly SJ, Gent M, Roberts RS, Dorian P,Roy D,Sheldon RS, et al.Canadian implantable defibrillator study (CIDS): a randomized trial of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator against amiodarone. Circulation 2000;101: 1297–1302.

- Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. Acomparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. N Eng lJ Med1997; 337:1576–1583.

- Kuck KH, Cappato R, Siebels J, Rüppel R. Randomized comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: the Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg (CASH). Circulation 2000;102: 748–754.

- Connolly SJ, Hallstrom AP, Cappato R, Schron EB, Kuck KH, Zipes DP, et al. Meta-analysis of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator secondary prevention trials. AVID, CASH and CIDS studies. Antiarrhythmics vs Implantable Defibrillator study. Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg. Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study. Eur Heart J 2000; 21:2071–2078.

- Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Klein H, etal. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease a thigh risk for ventricular arrhythmia. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1933–1940.

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:877–883.

- Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomizedstudyofthepreventionofsuddendeathinpatientswithcoronaryarterydisease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1882–1890.

- Bardy GH,Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, et al. Amiodaroneor an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:225–237.

- Zabel M, Willems R, Lubinski A, Bauer A, Brugada J, Conen D, et al. Clinical effectiveness of primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results of the EU-CERT-ICD controlled multicentre cohort study. Eur Heart J 2020;41: 3437–3447.

- Schrage B, Uijl A, Benson L, Westermann D, Ståhlberg M, Stolfo D, et al. Association between use of primary-prevention implantable cardioverterdefibrillators and mortality in patients with heart failure: a prospective propensity score-matched analysis from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Circulation 2019; 140:1530–1539.

- Køber L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, Haarbo J, Videbæk L, Korup E,et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1221–1230.

- Jukema JW, Timal RJ, Rotmans JI, Hensen LCR, Buiten MS, de Bie MK, et al. Prophylactic use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in the prevention of sudden cardiac death in dialysis patients. Circulation 2019;139: 2628–2638.

- Sticherling C, Arendacka B, Svendsen JH, Wijers S, Friede T, Stockinger J, et al. Sex differences in outcomes of primary prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy: combined registry data from eleven European countries. Europace 2018; 20:963–970.

- Junttila MJ, Pelli A, Kenttä TV, Friede T, Willems R, Bergau L, et al. Appropriate shocks and mortality in patients with versus without diabetes with prophylactic implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Diabetes Care 2020; 43:196–200.

- Koller MT, Schaer B, Wolbers M, Sticherling C, Bucher HC, Osswald S. Death without prior appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy: a competing risk study. Circulation 2008; 117:1918–1926.

- ClelandJ GF, Halliday BP, Prasad SK. Selecting patients with non ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy for ICDs: myocardial function, fibrosis, and what’s attached?JAmColl Cardiol 2017;70:1228–1231.

- Younis A, Goldberger JJ, Kutyifa V, Zareba W, Polonsky B, Klein H, et al. Predicted benefit ofan implantable cardioverter-defibrillator:the MADIT-ICD benefit score. Eur Heart J 2021;42: 1676–1684.

- Knops RE, Olde Nordkamp LRA, Delnoy P-PHM, Boersma LVA, Kuschyk J, El-Chami MF, et al. Subcutaneous or transvenous defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:526–536.

- ClelandJGF, DaubertJ-C, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, etal. The effect of cardiac resynchronization non morbidityand mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1539–1549.

- Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:2140–2150.

- Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Klein H, Brown MW, Daubert JP, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1329–1338.

- Masri A, Altibi AM, Erqou S, Zmaili MA, Saleh A, Al-Adham R, et al. Wearable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy for the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019; 5: 152–161.

- Garcia R, Combes N, Defaye P, Narayanan K, Guedon-Moreau L, Boveda S, et al. Wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with a transient risk of sudden cardiac death: the WEARIT-France cohort study. Europace 2021; 23:73–81.

- Olgin JE, Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Wranicz J, Malik R, Morin DP, et al. Wearable cardioverter-defibrillator after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2018;379: 1205–1215.

- Scott PA, Silberbauer J, McDonagh TA, Murgatroyd FD. Impact of prolonged implantable cardioverter-defibrillator arrhythmia detection times on outcomes: a meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm 2014; 11:828–835.

- Tan VH, Wilton SB, Kuriachan V, Sumner GL, Exner DV. Impact of programming strategies aimed at reducing nonessential implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapies on mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014; 7: 164–170.

- Saeed M, Hanna I, Robotis D, Styperek R, Polosajian L,Khan A, et al. Programming implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with primary prevention indication to prolong time to first shock: results from the PROVIDE study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014; 25:52–59.

- Wilkoff BL, Fauchier L, Stiles MK, Morillo CA, Al-Khatib SM, AlmendralJ, etal. 2015 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on optimal implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming and testing. Europace 2016;18: 159–183.

- Stiles MK, Fauchier L, Morillo CA, Wilkoff BL, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRSfocusedupdateto2015expertconsensusstatement on optimal implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming and testing. Europace 2019;21: 1442–1443.

- Barsheshet A, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Jons C, Glikson M, Klein HU, etal.Long-term implications of cumulative right ventricular pacing among patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2011;8: 212–218.

- Wilkoff BL, Cook JR, Epstein AE, Greene HL, Hallstrom AP, Hsia H, et al. Dual-chamber pacing or ventricular backup pacing in patients with an implantable defibrillator: the Dual Chamber and VVI Implantable Defibrillator (DAVID) Trial. JAMA 2002;288: 3115–3123.

- Olshansky B, Day JD, Moore S, Gering L, Rosenbaum M, McGuire M, et al. Is dualchamber programming inferior to single-chamber programming in an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator? Results of the INTRINSIC RV (Inhibition of Unnecessary RV Pacing With AVSH in ICDs) study. Circulation 2007; 115:9–16.

- Hindricks G, Kühl M, Dagres N. The implantable cardioverter defibrillator, conclusions on sudden cardiac death, and future perspective. ESC CardioMed. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2022, p2370–2376.

- Gasparini M, Proclemer A, Klersy C, Kloppe A, Ferrer JBM, Hersi A, et al. Effect of long-detectionintervalvsstandard-detectionintervalforimplantablecardioverterdefibrillators on antitachycardia pacing and shock delivery: the ADVANCE III randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309: 1903–1911.

- Moss AJ, Schuger C, Beck CA, Brown MW, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, et al. Reduction in inappropriate therapy and mortality through ICD programming. N Engl J Med 2012;367: 2275–2283.

- Wilkoff BL, Ousdigian KT, Sterns LD, Wang ZJ, Wilson RD, Morgan JM, et al. A comparison of empiric to physician-tailored programming of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the prospective randomized multicenter EMPIRIC trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48: 330–339.

- Wilkoff BL, Williamson BD, Stern RS, Moore SL, LuF, Lee SW, et al. Strategic programming of detection and therapy parameters in implantable cardioverter defibrillators reduces shocks in primary prevention patients: results from the PREPARE (Primary Prevention Parameters Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52:541–550.

- Gilliam FR, Hayes DL, Boehmer JP, Day J, Heidenreich PA, Seth M, etal. Real world evaluation of dual-zone ICD and CRT-D programming compared to single-zone programming: the ALTITUDE REDUCES study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2011; 22:1023–1029.

- Hernandez-Ojeda J, Arbelo E, Borras R, Berne P, Tolosana JM, Gomez-Juanatey A, et al. Patients with Brugada syndrome and implanted cardioverter-defibrillators: long-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70:1991–2002.

- Gold MR, Weiss R, Theuns DAMJ, Smith W, Leon A, Knight BP, et al. Use of a discriminationalgorithmtoreduceinappropriateshockswithasubcutaneousimplantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2014; 11:1352–1358.

- Mesquita J, Cavaco D, Ferreira A, Lopes N, Santos PG, Carvalho MS, et al. Effectiveness of subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and determinants of inappropriate shock delivery. Int J Cardiol 2017; 232:176–180.

- Gold MR, Lambiase PD, El-Chami MF, Knops RE, Aasbo JD, Bongiorni MG, et al. Primary results from the understanding outcomes with the S-ICD in primary prevention Patients With Low Ejection Fraction (UNTOUCHED) trial. Circulation 2021; 143:7–17.

- Wathen MS, DeGroot PJ, Sweeney MO, Stark AJ, Otterness MF, Adkisson WO, et al. Prospective randomized multicenter trial of empirical antitachycardia pacing versus shocks for spontaneous rapid Tachycardia Reduces Shock Therapies (PainFREE Rx II) trial results. Circulation 2004; 110:2591–2596.

- Gulizia MM, Piraino L, Scherillo M, Puntrello C,Vasco C, Scianaro MC, et al. Arandomized study to compare ramp versus burst antitachycardia pacing therapies to treat fast ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: the PITAGORA ICD trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2009;2: 146–153.

- Saxon LA, Hayes DL, Gilliam FR, Heidenreich PA, Day J, Seth M, et al. Long-term outcome after ICD and CRT implantation and influence of remote device followup: the ALTITUDE survival study. Circulation 2010; 122:2359–2367.

- Varma N, Piccini JP, Snell J, Fischer A, Dalal N, Mittal S. The relationship between level of adherence to automatic wireless remote monitoring and survival in pacemaker and defibrillator patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65:2601–2610.

- Guédon-Moreau L, Kouakam C, Klug D, Marquié C, Brigadeau F, Boulé S, et al. Decreased delivery of inappropriate shocks achieved by remote monitoring of ICD: a substudy of the ECOST trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25: 763–770.

- Varma N, Michalski J, Epstein AE, Schweikert R. Automatic remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead and generator performance: the Lumos-T Safely RedUceS RouTine Office Device Follow-Up (TRUST) trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010;3: 428–436.

- Ploux S, Swerdlow CD, Strik M, Welte N, Klotz N, Ritter P, et al. Towards eradicationofinappropriatetherapiesforICDleadfailurebycombiningcomprehensive remote monitoring and lead noise alerts. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2018;29: 1125–1134.

- Ellenbogen KA, Gunderson BD, Stromberg KD, Swerdlow CD. Performance of Lead Integrity Alert to assist in the clinical diagnosis of implantable cardioverter defibrillator lead failures: analysis of different implantable cardioverter defibrillator leads. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6: 1169–1177.

- Swerdlow CD, Gunderson BD, Ousdigian KT, Abeyratne A, Sachanandani H, Ellenbogen KA. Downloadable software algorithm reduces inappropriate shocks caused by implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead fractures: aprospective study. Circulation 2010;122: 1449–1455.

- Ruwald MH, Abu-Zeitone A,Jons C,Ruwald A-C, Mc Nitt S, Kutyifa V, etal. Impact of carvedilol and metoprolol on inappropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy: the MADIT-CRT trial (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:1343–1350.

- Miyazaki S, Taniguchi H, Kusa S, Komatsu Y, Ichihara N, Takagi T, et al. Catheter ablation of atrial tachyarrhythmias causing inappropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks. Europace 2015;17: 289–294.

- Mainigi SK, Almuti K, Figueredo VM, Guttenplan NA, Aouthmany A, Smukler J, etal. Usefulness of radiofrequency ablation of supraventricular tachycardia to decrease inappropriate shocks from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Am J Cardiol 2012; 109:231–237.

- Kosiuk J, Nedios S, Darma A, Rolf S, Richter S, Arya A, et al. Impact of single atrial fibrillation catheter ablation on implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapies in patients with ischaemic and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. Europace 2014;16: 1322–1326.

- Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, EckardtL, Elvan A,et al. Early rhythm control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2020;383: 1305–1316.

- Gasparini M, Kloppe A, Lunati M, Anselme F, Landolina M, Martinez-Ferrer JB, etal. Atrioventricular junction ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy: positive impacton ventricular arrhythmias, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies and hospitalizations: atrioventricular junction ablation in CRT patients with AF. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20:1472–1481.

- Gasparini M, Galimberti P. Rate control: ablation and device therapy (ablate and pace). ESC CardioMed. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2022, p2159–2162.

- Kitamura T, Fukamizu S, Kawamura I, Hojo R, Aoyama Y, Komiyama K, et al. Long-term efficacy of catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients withBrugadasyndromeandanimplantablecardioverter-defibrillatortopreventinappropriate shock therapy. Heart Rhythm 2016;13: 1455–1459.

- Magyar-Russe llG, Thombs BD, Cai JX, Baveja T, Kuhl EA, Singh PP ,etal. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in adults with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2011; 71:223–231.

- Tzeis S, Kolb C, Baumert J, Reents T, Zrenner B, Deisenhofer I, et al. Effect of depression on mortality in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients—findings from the prospective LICAD study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34:991–997.

- Andersen CM, Theuns DAMJ, Johansen JB, Pedersen SS. Anxiety, depression, ventricular arrhythmias and mortality in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: 7 years’ follow-up of the MIDAS cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020;66: 154–160.

- Berg SK, Thygesen LC, Svendsen JH, Christensen AV, Zwisler A-D. Anxiety predicts mortality in ICD patients: results from the cross-sectional national CopenHeartI CD survey with register follow-up. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014; 37:1641–1650.

- Thylén I, Moser DK, Strömberg A, Dekker RA, Chung ML. Concerns about implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks mediate the relationship between actual shocks and psychological distress. Europace 2016; 18:828–835.

- Pedersen SS, van Domburg RT, The uns DAMJ, JordaensL, Erdman RAM. Concerns about the implantable cardioverter defibrillator: a determinant of anxiety and depressive symptoms independent of experienced shocks. Am Heart J 2005;149: 664–669.

- Frizelle DJ, Lewin B, Kaye G, Moniz-Cook ED. Development of a measure of the concerns held by people with implanted cardioverter defibrillators: the ICDC. Br J Health Psychol 2006;11: 293–301.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67:361–370.

- Frydensberg VS, Johansen JB, Möller S, Riahi S, Wehberg S, Haarbo J, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in Danish patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: prevalence and association with indication and sex up to 2 years of follow-up (data from the national DEFIB-WOMEN study). Europace 2020;22: 1830–1840.

- Hoogwegt MT, Kupper N, Theuns DAMJ, Zijlstra WP, Jordaens L, Pedersen SS. Undertreatment of anxiety and depression in patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: impact on health status. Health Psychol 2012;31: 745–753.

- Lane DA, Aguinaga L, Blomström – Lundqvist C, Boriani G, DanG-A, Hills MT, et al. Cardiac tachyarrhythmias and patient values and preferences for their management: the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and Sociedad Latino americana de Estimulación Cardíaca y Electrofisiología (SOLEACE). Europace 2015; 17:1747–1769.

- Dunbar SB, Dougherty CM, Sears SF, Carroll DL, Goldstein NE, Mark DB, et al. Educational and psychological interventions to improve outcomes for recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and their families: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 126:2146–2172.

- Sears SF, Sowell LDV, Kuhl EA, Kovacs AH, Serber ER, Handberg E, et al. The ICD shock and stress management program: a randomized trial of psychosocial treatment to optimize quality of life in ICD patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007; 30:858–864.

- Berg SK, Rasmussen TB, Herning M, Svendsen JH, Christensen AV, Thygesen LC. Cognitive behavioural therapy significantly reduces anxiety in patients with implanted cardioverter defibrillator compared with usual care: findings from the Screen-ICD randomised controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020; 27:258–268.

- Schulz SM, Ritter O, Zniva R, Nordbeck P, Wacker C, Jack M, et al. Efficacy of a web-based intervention for improving psychosocial well-being in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: the randomized controlled ICD- FORUM trial. Eur Heart J 2020; 41:1203–1211.

- van den Broek KC, Tekle FB, Habibović M, Alings M, van der Voort PH, Denollet J. Emotional distress, positive affect, and mortality in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Int J Cardiol 2013; 165: 327–332.

- Hauptman PJ, Chibnall JT, Guild C, Armbrecht ES. Patient perceptions, physician communication, and the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 571–577.

- Cikes M, Jakus N, Claggett B, Brugts JJ, Timmermans P, Pouleur A-C, et al. Cardiac implantableelectronicdeviceswithadefibrillatorcomponentandall-cause mortality in left ventricular assist device carriers: results from the PCHF-VAD registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 1129–1141.

- Galand V, Flécher E, Auffret V, Boulé S, Vincentelli A, Dambrin C, et al. Predictors and clinical impact of late ventricular arrhythmias in patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4: 1166–1175.

- Nakahara S, Chien C, Gelow J, Dalouk K, Henrikson CA, Mudd J, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias after left ventricular assist device. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6: 648–654.

- Clerkin KJ, Topkara VK, Demmer RT, Dizon JM, Yuzefpolskaya M, Fried JA, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device: an analysis of the INTERMACS registry. JACC Heart Fail 2017; 5:916–926.

- Oz MC, Rose EA, Slater J, Kuiper JJ, Catanese KA, Levin HR. Malignant ventricular arrhythmiasare well toleratedin patients receiving long-term left ventricular assist devices. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24: 1688–1691.

- Potapov EV, Antonides C, Crespo-Leiro MG, Combes A, Färber G, Hannan MM, etal.2019EACTSExpertConsensusonlong-termmechanicalcirculatorysupport. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 56:230–270.

- . Makki N, Mesubi O, Steyers C, Olshansky B, Abraham WT. Meta-analysis of the relation of ventricular arrhythmias to all-cause mortality after implantation of a left ventricular assist device. Am J Cardiol 2015;116: 1385–1390.

- Yoruk A, Sherazi S, Massey HT, Kutyifa V, McNitt S, Hallinan W, et al. Predictors and clinical relevance of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ambulatory patients with a continuous flow left ventricular assist device. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13:1052–1056.

- Bedi M, Kormos R, Winowich S, Mc Namara DM, Mathier MA, Murali S. Ventricular arrhythmias during left ventricular assist device support. Am J Cardiol 2007;99: 1151–1153.

- Brenyo A, Rao M, Koneru S, Hallinan W, Shah S, Massey HT, etal. Riskofmortality for ventricular arrhythmia in ambulatory LVAD patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012;23: 515–520.

- Vakil K, Kazmirczak F, Sathnur N, Adabag S, Cantillon DJ, Kiehl EL, etal. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in patients with left ventricular assist devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2016; 4:772–779.

- Refaat MM, Tanaka T, Kormos RL, McNamara D, Teuteberg J, Winowich S, et al. Survival benefit of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in left ventricular assist device-supported heart failure patients. J Card Fail 2012;18: 140–145.

- Cantillon DJ, Tarakji KG, Kumbhani DJ, Smedira NG, Starling RC, Wilkoff BL. Improvedsurvivalamongventricularassistdevicerecipientswithaconcomitantimplantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2010;7: 466–471.

- Joyce E, Starling RC. HFrEF other treatment: ventricular assist devices. ESC CardioMed. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2022, p1884–1889.

- Younes A, Al-Kindi SG, Alajaji W, Mackall JA, Oliveira GH. Presence of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and wait-list mortality of patients supported with left ventricular assist devices as bridge to heart transplantation. Int J Cardiol 2017; 231:211–215.

- Agrawal S, Garg L, Nanda S, Sharma A, Bhatia N, Manda Y, etal. The role of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with continuous flow left ventricular assist devices – a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2016;222: 379–384.

- Blomström-Lundqvist C, Traykov V, Erba PA, Burri H, Nielsen JC, Bongiorni MG, et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) incollaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Europace 2020;22: 515–549.

- Burri H, Starck C, Auricchio A, Biffi M, Burri M, D’Avila A, et al. EHRA expert consensus statement and practical guide on optimal implantation technique for conventional pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin-American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace 2021; 23:983–1008.

- Tarakji KG, Mitta lS, Kennergren C, Corey R, Poole JE, Schloss E, etal. Antibacterial envelope to prevent cardiac implantable device infection. N Engl J Med 2019;380: 1895–1905.

- Atti V, Turagam MK, Garg J, Koerber S, Angirekula A, Gopinathannair R, et al. Subclavian and axillary vein access versus cephalic vein cutdown fo rcardiac implantable electronic device implantation: ameta-analysis. JACCCl in Electrophysiol 2020; 6: 661–671.

- Benz AP, Vamos M, Erath JW, Hohnloser SH. Cephalic vs. subclavian lead implantation in cardiac implantable electronic devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2019; 21:121–129.

- Chan N-Y, Kwong N-P, Cheong A-P. Venous access and long-termpacemaker lead failure: comparing contrast-guided axillary vein puncture with subclavian puncture and cephalic cutdown. Europace 2017;19: 1193–1197.

- Defaye P, Boveda S, Klug D, Beganton F, Piot O, Narayanan K, etal. Dual-vs.singlechamber defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death: long-term follow-up of the Défibrillateur Automatique Implantable-Prévention Primaire registry. Europace 2017; 19:1478–1484.

- Dewland TA, Pellegrini CN, Wang Y, Marcus GM, Keung E, Varosy PD. Dual-chamberimplantablecardioverter-defibrillator selection is associated within creased complication rates and mortality among patients enrolled in the NCDR implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:1007–1013.

- Friedman PA, Bradley D, Koestler C, Slusser J, Hodge D, Bailey K, etal. Aprospective randomized trial of single- or dual-chamber implantable cardioverter defibrillators to minimize inappropriate shock risk in primary sudden cardiac death prevention. Europace 2014;16: 1460–1468.

- Chen B-W, Liu Q, Wang X, Dang A-M. Are dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators really better than single-chamberones ? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2014; 39:273–280.

- Epstein LM, Love CJ, Wilkoff BL, Chung MK, Hackler JW, Bongiorni MG, et al. Superior vena cava defibrillator coils make transvenous lead extraction more challenging and riskier. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61: 987–989.

- Larsen JM, Hjortshøj SP, Nielsen JC, Johansen JB, Petersen HH, Haarbo J, et al. Single-coil and dual-coil defibrillator leads and association with clinical outcomes in a complete Danish nationwide ICD cohort. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13:706–712.

- Kumar KR, Mandleywala SN, Madias C, Weinstock J, Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, et al. Single coil implantable cardioverter defibrillator leads in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2020;125: 1896–1900.

- Friedman PA, Rasmussen MJ, Grice S, TrustyJ, Glikson M, Stanton MS. Defibrillation thresholds areincreased by right-sided implantation of totallytransvenous implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1999;22: 1186–1192.

- Stoevelaar R, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Bhagwandien RE, van Bruchem-Visser RL, Theuns DA, van der Heide A, et al. The incidence and impact of implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks in the last phase of life: an integrated review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2018; 17:477–485.

- Kapa S, Mueller PS, Hayes DL, Asirvatham SJ. Perspectives on withdrawing pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies at end of life: results of a survey of medical and legal professionals and patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:981–990.

- PadelettiL, Arnar DO, Boncinelli L, Brachman J, Camm JA, Daubert JC, etal. EHRA Expert Consensus Statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Europace 2010; 12:1480–1489.

- Stoevelaar R, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, vanDriel AG, Theuns DA, Bhagwandien RE , van Bruchem-Visser RL, etal. Trendsintime in the management of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator in the last phase of life: are trospective study of medical records. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019;18: 449–457.

- Kirkpatrick JN, Gottlieb M, Sehgal P, Patel R, Verdino RJ. Deactivation of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in terminal illness and end of life care. Am J Cardiol 2012; 109:91–94.

- Stevenson WG, Khan H, Sager P, Saxon LA, Middlekauff HR, Natterson PD, et al. Identification of reentry circuit sites during catheter mapping and radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardia late after myocardial infarction. Circulation 1993; 88 :1647–1670.

- deBakkerJM,van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ,Tasseron S, Vermeulen JT, DeJonge N,et al. Slow conduction in the infarcted human heart. “Zigzag” course of activation. Circulation 1993; 88: 915–926.

- De Chillou C, Lacroix D, Klug D, Magnin-PoullI, Marquié C, Messier M, etal. Isthmus characteristics of reentrant ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002; 105: 726–731.

- HsiaHH, Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE. Characterization Of Endocardial electrophysiological substrate in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2003; 108:704–710.

- Soejima K, Stevenson WG, SappJL, Selwyn AP, Couper G, EpsteinL M. Endocardial and epicardial radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardia associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43: 1834–1842.

- Miljoen H, State S, Dechillou C, Magninpoull I, Dotto P, Andronache M, et al. Electroanatomic mapping characteristics of ventricular tachycardia in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Europace 2005; 7:516–524.

- Priori SG, Blomström – Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, CammJ, etal. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The task force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J 2015;36: 2793–2867.

- Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, etal. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72:1677–1749.

- Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, Ackerman MJ, Calkins H, Darrieux FCC, etal. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: executive summary. Heart Rhythm 2019;16: e373–e407.

- Moss AJ, Greenberg H,Case RB, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Brown MW, etal. Long-term clinical course of patients after termination of ventricular tachyarrhythmia by an implanted defibrillator. Circulation 2004; 110:3760–3765.

- Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, Raitt MH, et al. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1009–1017.

- Sapp JL, Wells GA, Parkash R, Stevenson WG, BlierL, Sarrazin J-F, etal. Ventricular tachycardia ablation versus escalation of antiarrhythmic drugs. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:111–121.

- Piccini JP,Berger JS, O’Connor CM. Amiodarone for the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J 2009;30: 1245–1253.

- Palaniswamy C, Kolte D, Harikrishnan P, Khera S, Aronow WS, Mujib M, et al. Catheter ablation of postinfarction ventricular tachycardia: ten-year trends in utilization, in-hospital complications, and in-hospital mortality in the United States. Heart Rhythm 2014;11: 2056–2063.

- Caceres J, Jazayeri M, McKinnie J, Avitall B, Denker ST, Tchou P, etal. Sustained bundle branch reentry as a mechanism of clinical tachycardia. Circulation 1989;79: 256–270.

- Blanck Z, Dhala A, Deshpande S, Sra J, Jazayeri M, Akhtar M. Bundle branch reentrant ventricular tachycardia: cumulative experience in 48 patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1993;4: 253–262.

- Chen H, ShiL, Yang B, Ju W, Zhang F , Yang G, etal. Electrophysiological characteristics of bundle branch reentry ventricular tachycardia in patients without structural heart disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2018;11: e006049.

- Pathak RK, Fahed J, Santangeli P, Hyman MC, Liang JJ, Kubala M, et al. Long-term outcome of catheter ablation for treatment of bundle branch re-entrant tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018; 4:331–338.

- Stevenson WG, Wilber DJ, Natale A, Jackman WM, Marchlinski FE, Talbert T, etal. Irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation guided by electroanatomic mapping for recurrent ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction: the multicenter thermocool ventricular tachycardia ablation trial. Circulation 2008;118: 2773–2782.

- Della Bella P, Baratto F, Tsiachris D, Trevisi N, Vergara P, Bisceglia C, et al. Management of ventricular tachycardia in the setting of a dedicated unit for the treatment of complex ventricular arrhythmias: long-term outcome after ablation. Circulation 2013; 127: 1359–1368.

- Maury P, Baratto F, Zeppenfeld K, Klein G, Delacretaz E, Sacher F, et al. Radio-frequency ablation as primary management of well-tolerated sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in patients with structural heart disease and left ventricular ejection fraction over 30%. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1479–1485.

- Tung R, Vaseghi M, Frankel DS, Vergara P, Di Biase L,Nagashima K, et al. Freedom fromrecurrentventriculartachycardiaaftercatheterablationisassociatedwithimproved survival in patients with structural heart disease: an International VT Ablation Center Collaborative Group study. Heart Rhythm 2015;12: 1997–2007.

- Santangeli P, Zado ES, Supple GE, Haqqani HM, Garcia FC, Tschabrunn CM, et al. Long-term outcome with catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8: 1413–1421.

- Marchlinski FE, Haffajee CI, BeshaiJ F, Dickfeld T-ML, Gonzalez MD, Hsia HH, et al. Long-term success of irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation of sustained ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:674–683.

- Reddy VY, Reynolds MR, Neuzil P, Richardson AW, Taborsky M, Jongnarangsin K, et al. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2657–2665.

- Kuck K-H, Schaumann A, Eckardt L, Willems S, Ventura R, Delacrétaz E, et al. Catheterablationofstableventriculartachycardiabeforedefibrillatorimplantation in patients with coronary heart disease (VTACH): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 375:31–40.

- Anter E, Kleber AG, Rottmann M, Leshem E, Barkagan M, Tschabrunn CM, et al. Infarct-related ventricular tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4: 1033–1048.

- Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gottlieb CD, Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2000; 101:1288–1296.

- deChillou C, Groben L, Magnin-PoullI, Andronache M, Abbas MM, Zhang N, etal. Localizing the critical isthmus of postinfarct ventricular tachycardia: the value of pace-mapping during sinus rhythm. Heart Rhythm 2014;11: 175–181.

- Jaïs P, Maury P, Khairy P, Sacher F, NaultI, Komatsu Y, et al. Elimination of local abnormal ventricular activities: a new end point for substrate modification in patients with scar-related ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2012; 125:2184–2196.

- Berruezo A, Fernandez-Armenta J. Lines, circles, channels, and clouds: looking for the best design for substrate-guided ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Europace 2014;16: 943–945.

- Di Biase L, Burkhardt JD, Lakkireddy D, Carbucicchio C, Mohanty S, Mohanty P, et al. Ablation of stable VTs versus substrate ablation in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66: 2872–2882.

- Berruezo A, Fernández-ArmentaJ, Andreu D, Penela D, Herczku C,Evertz R, etal. Scar dechanneling: new method for scar-related left ventricular tachycardia substrate ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8: 326–336.

- Haïssaguerre M, Shoda M, Jaïs P, Nogami A, Shah DC, KautznerJ, etal. Mappingand ablation of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circulation 2002; 106:962–967.

- Shirai Y, Liang JJ, Santangeli P, Arkles JS, Schaller RD, Supple GE, et al. Comparison of the ventricular tachycardia circuit between patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies: detailed characterization by entrainment. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2019;12: e007249.

- Bhaskaran A, Tung R, Stevenson WG, Kumar S. Catheter ablation of VT in nonischaemic cardiomyopathies: endocardial, epicardial and intramural approaches. Heart Lung Circ 2019; 28:84–101.

- Tung R, Raiman M, Liao H, Zhan X, Chung FP, Nagel R, et al. Simultaneous endocardial and epicardial delineation of 3D reentrant ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 75:884–897.

- Dinov B, Fiedler L, Schönbauer R, Bollmann A, Rolf S, Piorkowski C, et al. Outcomes in catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy compared with ischemic cardiomyopathy: results from the Prospective Heart Centre of Leipzig VT (HELP-VT) Study. Circulation 2014;129: 728–736.

- Proietti R, Essebag V, Beardsall J, Hache P, Pantano A, Wulffhart Z, et al. Substrate-guided ablation of haemodynamically tolerated and untolerated ventricular tachycardia in patients with structural heart disease: effect of cardiomyopathy type and acute success on long-term outcome. Europace 2015; 17: 461–467.

- Ebert M, Richter S, Dinov B, Zeppenfeld K, Hindricks G. Evaluation and management of ventricular tachycardia in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2019;16: 624–631.

- Proietti R, Lichelli L, Lellouche N, Dhanjal T. The challenge of optimising ablation lesions in catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia. J Arrhythmia 2021;37: 140–147.

- Tokuda M, Sobieszczyk P, Eisenhauer AC, Kojodjojo P, Inada K, Koplan BA, et al. Transcoronary ethanol ablation for recurrent ventricular tachycardia after failed catheter ablation: an update. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4: 889–896.

- Kreidieh B, Rodríguez-Mañero M, Schurmann P, Ibarra-Cortez SH, Dave AS, Valderrábano M. Retrograde coronary venous ethanol infusion for ablation of refractory ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016;9: e004352.

- Nguyen DT, Tzou WS, Sandhu A, Gianni C, Anter ET ung R, etal. Prospective multicenter experience with cooled radiofrequency ablation using high impedance irrigantto target deep myocardial substrate refractory to standard ablation. JACCCl in Electrophysiol 2018; 4: 1176–1185.

- Stevenson WG, Tedrow UB, Reddy V, Abdel Wahab A, Dukkipati S, John R M, etal. Infusion needle radiofrequency ablation for treatment of refractory ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73: 1413–1425.

- Igarashi M, Nogami A, Fukamizu S, Sekiguchi Y, NittaJ, Sakamoto N, etal. Acute and long-term results of bipolar radiofrequency catheter ablation of refractory ventricular arrhythmias of deep intramural origin. Heart Rhythm 2020; 17:1500–1507.

- Della Bella P, Peretto G, Paglino G, Bisceglia C, Radinovic A, Sala S, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation for ventricular tachycardias originating from the interventricular septum: safety and efficacy in a pilot cohort study. Heart Rhythm 2020;17: 2111–2118.

- Cuculich PS, Schill MR, Kashani R, Mutic S, Lang A, Cooper D, et al. Noninvasive cardiac radiation for ablation of ventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med 2017;377: 2325–2336.

- Robinson CG, Samson PP, MooreK MS, Hugo GD, Knutson N, Mutic S, etal. Phase I/II trial of electrophysiology-guided noninvasive cardiac radioablation for ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2019; 139:313–321.

- Anter E, Hutchinson MD, Deo R, Haqqani HM, Callans DJ, Gerstenfeld EP, et al. Surgical ablation of refractory ventricular tachycardia in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4: 494–500.

- Fernández-Armenta J, Berruezo A, Andreu D, Camara O, Silva E, Serra L, et al. Three-dimensional architecture of scar and conducting channels based on high resolution ce-CMR: insights for ventricular tachycardia ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013; 6:528–537.

- Mahida S, Sacher F, Dubois R, Sermesant M, Bogun F, Haïssaguerre M, etal. Cardiac imaging in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2017;136: 2491–2507.

- Andreu D, Penela D, AcostaJ,Fernández-ArmentaJ, Perea RJ, Soto-Iglesias D, etal. Cardiac magnetic resonance–aided scarde channeling: influence on acute and longterm outcomes. Heart Rhythm 2017;14: 1121–1128.

- Kuo L, Liang JJ, aemic cardiomyopathy. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2020; 8: 255–264. 514. Roca-Luque I, Van Breukelen A, Alarcon F, Garre P, Tolosana JM, Borras R, et al. Ventricular scar channel entrances identified by new wideband cardiac magnetic resonance sequence to guide ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with cardiac defibrillators. Europace 2020;22: 598–606.

- Betensky BP, Marchlinski FE. Outcomes of catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in the setting of structural heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2016; 18:68. 516. Dukkipati SR, Koruth JS, Choudry S, Miller MA, Whang W, Reddy VY. Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70:2924–2941.

- Zeppenfeld K. Ventricular tachycardia ablation in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4: 1123–1140.

- Guandalini GS, Liang JJ, Marchlinski FE. Ventricular tachycardia ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5: 1363–1383.

- Peichl P, Wichterle D, Pavlu L, Cihak R, Aldhoon B, Kautzner J. Complications of catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia: a single-center experience. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014; 7: 684–690.

- Katz DF, Turakhia MP, Sauer WH, Tzou WS, Heath RR, Zipse MM, et al. Safety of ventricular tachycardia ablation in clinical practice: findings from 9699 hospital discharge records. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015; 8: 362–370.

- Cheung JW, Yeo I, Ip JE,Thomas G, LiuCF, Markowitz SM, et al. Outcomes, costs, and 30-day readmissions after catheter ablation of myocardial infarct–associated ventricular tachycardia in the real world: nationwide readmissions database 2010 to 2015. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2018;11: e 006754.