Trưởng ban: PGS.TS.BS PHẠM NGUYỄN VINH

PGS.TS.BS HỒ HUỲNH QUANG TRÍ

Tham gia biên soạn:

BSCKII. LÊ THỊ ĐẸP, ThS.BSCKII. TRẦN THỊ TUYẾT LAN,

ThS.BSCKII. HUỲNH THANH KIỀU, ThS.BS. PHẠM ĐỖ ANH THƯ,

BSCKI. VŨ NĂNG PHÚC, BSCKI. PHẠM THỤC MINH THỦY

Biên tập: TRẦN THỊ THANH NGA

(…)

3.16. Xét nghiệm và tư vấn về di truyền

Xét nghiệm về di truyền được chỉ định ở bệnh nhân tăng áp động mạch phổi có tính gia đình, vô căn hay tăng áp động mạch phổi liên quan đến bệnh lý tĩnh mạch hoặc mao mạch, liên quan đến thuốc gây chán ăn.

Các bất thường gene có thể gặp trong tăng áp động mạch phổi vô căn và di truyền: BMPR2, ATP13A3, AQP1, ABCC8, KCNK, SMAD9,…tính trội, di truyền trên nhiễm sắc thể thường.

Các bác sĩ tư vấn về di truyền phải được đào tạo trước khi tư vấn cho người bệnh làm xét nghiệm này cũng như khi có kết quả.

4. Các bước chẩn đoán tăng áp phổi

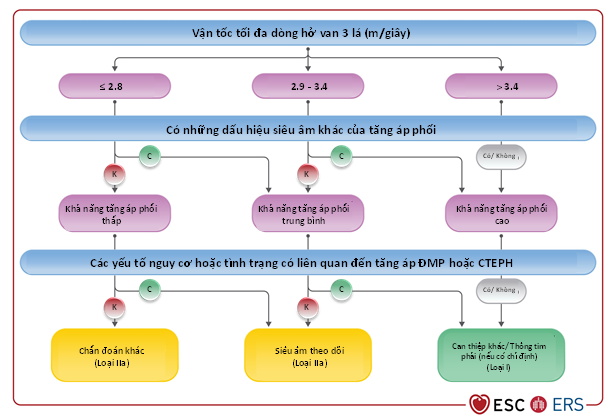

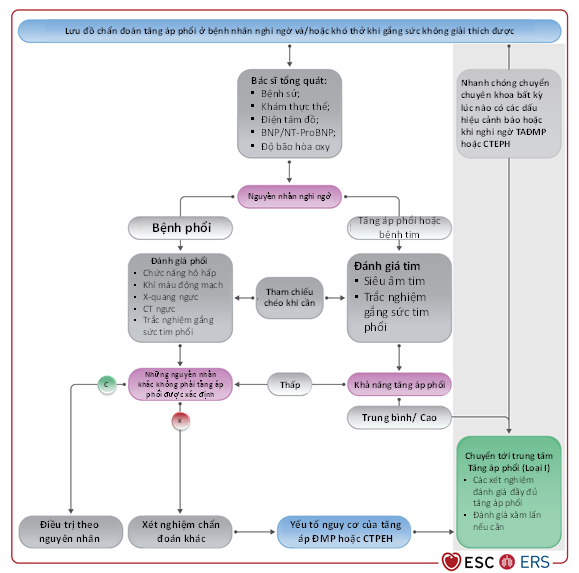

Các bước chẩn đoán tăng áp phổi được trình bày trong Hình 4.1 và Hình 4.2 bên dưới.

Hình 4.1 Khả năng tăng áp phổi dựa vào siêu âm và những đánh giá khác cần làm thêm

Bước 1: Nghi ngờ

Khi bệnh nhân có triệu chứng nghi ngờ tăng áp phổi hay khó thở không rõ nguyên nhân, cần làm các bước sau:

- Hỏi bệnh sử, tiền sử gia đình mắc bệnh tăng áp phổi

- Khám lâm sàng, bao gồm đo huyết áp, nhịp tim, SpO2, khám toàn thân.

- Đo ECG, xét nghiệm BNP/NT-ProBNP

Bước 2: Phát hiện

Phát hiện tăng áp phổi với các cận lâm sàng không xâm nhập về chức năng tim và phổi. Trong đó siêu âm tim là bước quan trọng nhất để đánh giá khả năng bị tăng áp phổi bất kể nguyên nhân gì. Ngoài ra, siêu âm tim còn đánh giá được các bất thường ở tim có thể gây tăng áp phổi như bệnh tim bẩm sinh có luồng thông, bệnh van tim, rối loạn chức năng tâm thu, tâm trương thất trái, thất phải,…

Bước 3: Xác định

Thường làm ở trung tâm chuyên về tăng áp phổi để xác định chẩn đoán. Bệnh nhân được làm đầy đủ các cận lâm sàng cần thiết để xác định chẩn đoán và phân biệt nguyên nhân tăng áp phổi theo bảng phân loại ở bên dưới. Người bệnh thường được làm trắc nghiệm xâm nhập trong bước này.

Hình 4.2 Lưu đồ các bước chẩn đoán tăng áp phổi ở bệnh nhân nghi ngờ/ khó thở không rõ nguyên nhân

Các dấu hiệu lâm sàng cảnh báo người bệnh cần nhập viện hoặc được đánh giá và theo dõi điều trị với các bác sĩ chuyên gia về tăng áp phổi như bệnh tiến triển nhanh hoặc có triệu chứng nặng (phân độ chức năng WHO III-IV), triệu chứng lâm sàng của suy thất phải, ngất, tình trạng cung lượng tim thấp, rối loạn nhịp dung nạp kém, huyết động không ổn định (tụt huyết áp, nhịp tim nhanh). Đặc biệt ở những bệnh nhân có rối loạn chức năng thất phải trên siêu âm tim, tăng chất chỉ điểm sinh học của tim và/hoặc huyết động không ổn định phải nhanh chóng chuyển đến chuyên gia về bệnh tăng áp phổi để đánh giá và điều trị.

Bảng 4.1 Các đặc điểm chẩn đoán của các dạng tăng áp phổi khác nhau

| Công cụ | Đặc điểm hoặc dấu hiệu đặc trưng | Nhóm 1 (Tăng áp động mạch phổi) | Nhóm 2 (TAP liên quan bệnh tim trái) | Nhóm 3 (TAP liên quan bệnh phổi) | Nhóm 4 (TAP liên quan đến tắc nghẽn ĐMP) |

| Biểu hiện lâm sàng | Đặc điểm lâm sàng | Nhiều độ tuổi, nhưng thường gặp ở phụ nữ, trẻ.

Biểu hiện lâm sàng phụ thuộc vào bệnh liên quan. |

Thường ở người lớn tuổi, ưu thế phụ nữ nếu là HFpEF.

Bệnh sử và khám lâm sàng gợi ý bệnh tim trái. |

Thường ở người lớn tuổi, ưu thế nam, hút thuốc lá.

Bệnh sử và khám lâm sàng gợi ý bệnh phổi. |

Nhiều độ tuổi, tỉ lệ nam nữ bằng nhau.

Tiền sử có VTE (CTEPH có thể xảy ra ở người không có tiền căn VTE). Có yếu tố nguy cơ của CTEPH. |

| Nhu cầu oxy do giảm oxy máu | Ít gặp, ngoại trừ tình trạng DLCO thấp hoặc luồng thông phải-trái. | Ít gặp | Thường gặp, giảm oxy máu nghiêm trọng trong TAP nặng. | Ít gặp, thường gặp ở những ca nặng có tắc nghẽn ĐMP ở xa nặng. | |

| X-quang phổi | ↑ kích thước của NP/TP/ĐMP

Hình ảnh mạch máu cắt cụt |

↑ kích thước của NT/TT

Bóng tim to Đôi khi có dấu hiệu sung huyết phổi (phù mô kẽ/ đường Kerley, phù phế nang, tràn dịch màng phổi) |

Dấu hiệu của bệnh nhu mô phổi | ↑ kích thước của NP/TP/ĐMP

Số lượng và kích thước của mạch máu ngoại vi giảm Đôi khi có các dấu hiệu của nhồi máu phổi |

|

| Chức năng hô hấp và khí máu động mạch | Suy giảm chức năng hô hấp/phế dung ký | Bình thường hoặc giảm nhẹ | Bình thường hoặc giảm nhẹ | Bất thường khi được xác định bởi bệnh phổi nền | Bình thường hoặc giảm nhẹ |

| DLCO | Bình thường hoặc giảm nhẹ đến trung bình (DLCO thấp trong TAĐMP do bệnh xơ cứng hệ thống, bệnh tắc nghẽn tĩnh mạch phổi, TAĐMP vô căn) | Bình thường hoặc giảm nhẹ đến trung bình, đặc biệt trong HFpEF | Thường rất thấp (< 45% giá trị tiên đoán) | Bình thường hoặc giảm nhẹ đến trung bình | |

| Khí máu động mạch

PaO2 PaCO2 |

Bình thường hay ↓ Giảm |

Bình thường hay ↓ Thường là bt |

Giảm Giảm, bình thường hoặc tăng |

Bình thường hay ↓ Bình thường hay ↓ |

|

| Siêu âm tim | Dấu hiệu của tăng áp phổi (tăng sPAP, lớn TP/NP)

Có thể có bệnh tim bẩm sinh |

Dấu hiệu của bệnh tim trái (suy tim PXTM giảm, suy tim PXTM bảo tồn, bệnh van tim) và tăng áp phổi (tăng sPAP, lớn TP/NP) | Dấu hiệu của tăng áp phổi (tăng sPAP, lớn TP/NP)

|

Dấu hiệu của tăng áp phổi (tăng sPAP, lớn TP/NP)

|

|

| Xạ ký phổi | Planar-SPECT V/Q | Bình thường hoặc tương thích (matched) | Bình thường hoặc tương thích | Bình thường hoặc tương thích | Bất thường thông khí tưới máu phổi |

| CT ngực | Dấu hiệu của tăng áp phổi hoặc bệnh tắc nghẽn tĩnh mạch phổi | Dấu hiệu của bệnh tim trái

Phù phổi Dấu hiệu của tăng áp phổi |

Dấu hiệu của bệnh nhu mô phổi

Dấu hiệu của tăng áp phổi |

Khiếm khuyết đổ đầy trong lòng mạch máu, tưới máu thể khảm, động mạch phế quản dãn

Dấu hiệu của tăng áp phổi |

|

| Nghiệm pháp gắng sức tim phổi | VE/VCO2 cao, PETCO2 thấp, giảm trong lúc gắng sức

Không EOV |

VE/VCO2 tăng nhẹ, PETCO2 bình thường, tăng trong lúc gắng sức

EOV |

VE/VCO2 tăng nhẹ, PETCO2 bình thường, tăng trong lúc gắng sức

|

VE/VCO2 cao, PETCO2 thấp, giảm trong lúc gắng sức

Không EOV |

|

| Thông tim phải | Tăng áp phổi tiền mao mạch | Tăng áp phổi hậu mao mạch | Tăng áp phổi tiền mao mạch | Tăng áp phổi tiền (hoặc hậu) mao mạch |

Bảng 4.2 Các khuyến cáo cho chẩn đoán tăng áp phổi

| Khuyến cáo | Loại | MCC |

| Siêu âm tim | ||

| Siêu âm tim là phương tiện chẩn đoán không xâm nhập đầu tiên được chọn lựa khi nghi ngờ tăng áp phổi. | I | B |

| Khuyến cáo đánh giá khả năng bị tăng áp phổi dựa vào vận tốc dòng hở 3 lá bất thường và các dấu hiệu siêu âm khác của tăng áp phổi. | I | B |

| Ngưỡng vận tốc dòng hở 3 lá > 2.8 m/giây trên siêu âm gợi ý khả năng bị tăng áp phổi. | I | C |

| Dựa vào khả năng tăng áp phổi trên siêu âm, chỉ định làm thêm các cận lâm sàng khác dựa vào bệnh cảnh lâm sàng (vd, triệu chứng cơ năng và các yếu tố nguy cơ hoặc các bệnh cảnh có liên quan đến tăng áp động mạch phổi/CTEPH). | IIa | B |

| Bệnh nhân có triệu chứng cơ năng, khả năng mắc bệnh tăng áp phổi ở độ mức trung bình, nên làm thêm trắc nghiệm gắng sức tim phổi để xác định khả năng bị tăng áp phổi. | IIb | C |

| Hình ảnh học | ||

| Xạ ký thông khí/ tưới máu phổi hoặc tưới máu phổi được khuyến cáo thực hiện cho bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi không rõ nguyên nhân để tìm CTEPH. | I | C |

| Chụp CT động mạch phổi cản quang được chỉ định ở bệnh nhân nghi ngờ CTEPH. | I | C |

| Các xét nghiệm sinh hóa, huyết học, miễn dịch thường quy, HIV, chức năng tuyến giáp được khuyến cáo ở tất cả bệnh nhân tăng áp động mạch phổi để tìm các bệnh có liên quan. | I | C |

| Chỉ định siêu âm bụng để tầm soát nguyên nhân tăng áp tĩnh mạch cửa | I | C |

| CT ngực nên xem xét cho tất cả bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi | IIa | C |

| Chụp mạch máu xóa nền nên được xem xét ở bệnh nhân CTEPH | IIa | C |

| Các test chẩn đoán khác | ||

| Đo chức năng phổi với DLCO nên là trắc nghiệm đánh giá đầu tiên ở tất cả bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi | I | C |

| Chống chỉ định sinh thiết phổi qua mở ngực hoặc nội soi ở bệnh nhân tăng áp động mạch phổi. | III | C |

5. Tầm soát và phát hiện sớm bệnh tăng áp phổi

Phần lớn bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi được phát hiện và điều trị trễ. Thời gian trung bình từ lúc có triệu chứng cho đến khi được chẩn đoán xác định là trên 2 năm do đó đã bỏ qua cơ hội điều trị sớm cho người bệnh. Chúng ta cần tầm soát cho những đối tượng sau: (1) nhóm có nguy cơ cao, không triệu chứng bao gồm những bệnh nhân bị bệnh xơ cứng hệ thống, mang đột biến gen BMPR2, thế hệ thứ nhất trong gia đình có người bệnh tăng áp động mạch phổi di truyền, bệnh nhân trước ghép gan; (2) chẩn đoán sớm ở nhóm bệnh nhân nguy cơ cao và có triệu chứng như tăng áp tĩnh mạch cửa, nhiễm HIV, bệnh mô liên kết không có xơ cứng hệ thống; (3) nhóm bệnh nhân có tiền sử thuyên tắc phổi, khó thở không rõ nguyên nhân, hoặc những người có nguy cơ liên quan đến lối sống.

Các cận lâm sàng tấm soát gồm: đo ECG, siêu âm tim qua thành ngực (đánh giá áp lực động mạch phổi lúc nghỉ), xét nghiệm chất chỉ điểm sinh học như NT-ProBNP, đo chức năng hô hấp (DLCO hoặc tỉ số [FVC]/DLCO) và trắc nghiệm gắng sức tim phổi (CPET).

Trong bệnh xơ cứng rải rác, tỉ lệ bị tăng áp động mạch phổi từ 5-19%, với tần suất mắc từ 0.7 – 1.5% hàng năm. Những người được phát hiện sớm có tỉ lệ sống còn cao hơn những người không được tầm soát sớm. Việc tầm soát nên được thực hiện mỗi năm một lần với sự kết hợp của các phương thức tầm soát đã trình bày trên, một số trường hợp cần thiết có thể làm thông tim phải. Các yếu tố nguy cơ dễ bị tăng áp động mạch phổi ở nhóm bệnh nhân xơ cứng hệ thống là: bệnh kéo dài, có triệu chứng khó thở, khô miệng, khô mắt, loét đầu ngón, lớn tuổi, giới nam, kháng thể kháng centromere dương tính, bệnh phổi mô kẽ nhẹ, DLCO thấp, tăng tỉ lệ FVC/DLCO, tăng NT-ProBNP.

Người mang đột biến gen BMPR2 có 20% nguy cơ tiến triển thành tăng áp động mạch phổi trong suốt cuộc đời, tỉ lệ thấm ở nữ cao hơn ở nam (42% so với 14%). Hiện nay chưa có khuyến cáo nào chấp nhận tầm soát thường quy cho những người mang đột biến gen này, có lẽ còn chờ thêm nghiên cứu lớn hơn đa trung tâm, đa quốc gia.

Tăng áp tĩnh mạch cửa: ước tính có 1-2% bệnh nhân bệnh gan mãn và tăng áp tĩnh mạch cửa đưa đến tăng áp phổi, thường gặp ở người đã có làm thông nối cửa chủ qua tĩnh mạch cảnh hoặc đã ghép gan. Siêu âm tim là phương tiện tầm soát phổ biến nhất, khi áp lực động mạch phổi tâm thu đo trên siêu âm sPAP > 50 mmHg, khả năng chẩn đoán tăng áp động mạch phổi mức độ trung bình đến nặng có độ nhạy là 97% và độ đặc hiệu là 77%. Một số tác giả đề nghị nên làm thông tim phải khi sPAP > 38 mmHg. Bệnh nhân đang chờ ghép gan nên siêu âm tim đánh giá áp lực động mạch phổi mỗi năm một lần.

CTEPH là một biến chứng ít gặp và dễ bị bỏ sót sau thuyên tắc phổi cấp. Tần suất của CTEPH sau thuyên tắc phổi cấp là 0.6%. Siêu âm tim được chỉ định làm đầu tiên ở bệnh nhân nghi ngờ CTEPH. Hơn 50% bệnh nhân còn khiếm khuyết tưới máu phổi kéo dài sau thuyên tắc phổi cấp dù lâm sàng không rõ ràng. Bệnh nhân sau thuyên tắc phổi cấp nên được theo dõi và đánh giá CTEPH sau 3-6 tháng.

Bảng 5.1 Khuyến cáo tầm soát và phát hiện sớm tăng áp động mạch phổi và CTEPH

| Khuyến cáo | Loại | MCC |

| Bệnh xơ cứng hệ thống | ||

| Những bệnh nhân có bệnh xơ cứng hệ thống được khuyến cáo đánh giá nguy cơ tăng áp động mạch phổi hàng năm. | I | B |

| Bệnh nhân có bệnh xơ cứng hệ thống có thời gian bệnh > 3 năm, FVC ≥ 40% và DLCO < 60% khuyến cáo dùng lưu đồ phát hiện bệnh để tìm tăng áp động mạch phổi không triệu chứng. | I | B |

| Bệnh nhân xơ cứng hệ thống khó thở không giải thích được khi làm các test không xâm nhập, có chỉ định thông tim phải để loại trừ bệnh tăng áp động mạch phổi. | I | C |

| Đánh giá nguy cơ tăng áp động mạch phổi dựa trên triệu chứng khó thở kết hợp với siêu âm tim, hoặc chức năng hô hấp và BNP/NT-ProBNP ở bệnh nhân có bệnh xơ cứng hệ thống. | IIa | B |

| Chính sách đánh giá nguy cơ tăng áp động mạch phổi nên được thực hiện ở bệnh viện quản lý bệnh nhân xơ cứng hệ thống. | IIa | C |

| Bệnh nhân xơ cứng hệ thống có triệu chứng nên làm thêm siêu âm tim gắng sức hoặc trắc nghiệm gắng sức tim phổi, hoặc MRI tim trước khi có quyết định thông tim phải. | IIb | C |

| Bệnh nhân có bệnh mô liên kết có đặc điểm chồng lấp với bệnh xơ cứng hệ thống, hằng năm nên đánh giá nguy cơ tăng áp động mạch phổi. | IIb | C |

| Bệnh phổi do huyết khối thuyên tắc mạn tính/ Tăng áp phổi do huyết khối thuyên tắc mạn tính (CTEPD/CTEPH) | ||

| Bệnh nhân có triệu chứng khó thở kéo dài hoặc mới khởi phát, hoặc hạn chế khả năng gắng sức sau thuyên tắc phổi cần được đánh giá thêm để chẩn đoán CTEPH/CTEPD. | I | C |

| Bệnh nhân có triệu chứng với bất tương hợp tưới máu phổi kéo dài trên 3 tháng sau điều trị kháng đông thuyên tắc phổi cấp khuyến cáo nên chuyển viện đến trung tâm tăng áp phổi/CTEPH sau khi xem xét kết quả siêu âm tim, BNP/NT-ProBNP và/hoặc trắc nghiệm gắng sức tim phổi. | I | C |

| Những trường hợp khác | ||

| Xem xét tư vấn nguy cơ tăng áp động mạch phổi và tầm soát hằng năm ở những người có mang đột biến gen gây tăng áp động mạch phổi và ở thế hệ thứ nhất của bệnh nhân tăng áp động mạch phổi di truyền. | I | B |

| Bệnh nhân có chỉ định ghép gan cần làm siêu âm tim để tầm soát tăng áp phổi. | I | C |

| Các cận lâm sàng khác (siêu âm tim, BNP/NT-ProBNP, chức năng hô hấp, và hoặc trắc nghiệm gắng sức tim phổi) nên được xem xét làm thêm vào ở bệnh nhân có triệu chứng trong bệnh mô liên kết, tăng áp tĩnh mạch cửa, hoặc nhiễm HIV để tầm soát bệnh tăng áp động mạch phổi. | IIa | B |

6. Tăng áp động mạch phổi (nhóm 1)

6.1. Đặc điểm lâm sàng

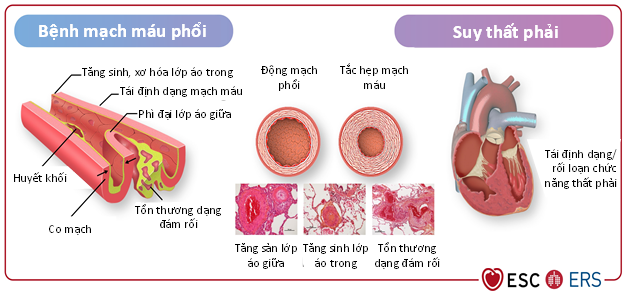

Các triệu chứng lâm sàng của tăng áp động mạch phổi (TAĐMP) không đặc hiệu và chủ yếu liên quan với rối loạn chức năng thất phải tiến triển là một hậu quả của bệnh mạch máu phổi tiến triển (Hình 6.1). Biểu hiện lâm sàng của TAĐMP có thể thay đổi bởi bệnh gây TAĐMP cũng như các bệnh đồng mắc.

Hình 6.1 Sinh lý bệnh của tăng áp động mạch phổi

6.2. Đánh giá mức độ nặng và nguy cơ

6.2.1. Các thông số lâm sàng

Khám lâm sàng là một phần then chốt trong đánh giá bệnh nhân TAĐMP, cung cấp những thông tin có giá trị giúp xác định mức độ nặng của bệnh, sự cải thiện, sự xấu đi hoặc tình trạng ổn định. Trong quá trình theo dõi, những thay đổi của độ chức năng theo Tổ chức y tế thế giới (World Health Organization functional class – WHO-FC), những đợt đau ngực, rối loạn nhịp, ho ra máu, ngất và các dấu hiệu của suy thất phải cung cấp thông tin quan trọng. Khám lâm sàng bao gồm đánh giá tần số tim, nhịp tim, huyết áp, tím, phồng tĩnh mạch cảnh, phù, báng bụng và tràn dịch màng phổi. WHO-FC (Bảng 6.1) là một trong các yếu tố dự báo sống còn mạnh nhất, cả vào thời điểm chẩn đoán lẫn trong quá trình theo dõi, và sự xấu đi của WHO-FC là một trong các dấu hiệu cảnh báo quan trọng nhất về sự tiến triển của bệnh. Khi tình huống này xảy ra, cần tiến hành các khảo sát bổ sung để nhận diện các nguyên nhân khiến tình trạng lâm sàng xấu đi.

Bảng 6.1 Phân độ chức năng bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi theo Tổ chức y tế thế giới

(WHO-FC)

| Độ | Mô tả |

| Độ I | Bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi không bị hạn chế hoạt động thể lực. Hoạt động thể lực thông thường không gây khó thở hoặc mệt quá mức, đau ngực hoặc gần ngất. |

| Độ II | Bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi bị hạn chế nhẹ hoạt động thể lực. Bệnh nhân dễ chịu lúc nghỉ. Hoạt động thể lực thông thường gây khó thở hoặc mệt quá mức, đau ngực hoặc gần ngất. |

| Độ III | Bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi bị hạn chế rõ hoạt động thể lực. Bệnh nhân dễ chịu lúc nghỉ. Hoạt động thể lực dưới mức thông thường gây khó thở hoặc mệt quá mức, đau ngực hoặc gần ngất. |

| Độ IV | Bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi không thể thực hiện bất cứ hoạt động thể lực nào mà không bị triệu chứng. Bệnh nhân có các dấu hiệu suy thất phải. Khó thở và/hoặc mệt hiện diện cả khi nghỉ. Sự khó chịu tăng khi có bất cứ một hoạt động thể lực nào. |

6.2.2. Hình ảnh học

Khảo sát hình ảnh học đóng vai trò thiết yếu trong theo dõi bệnh nhân TAĐMP.

- Siêu âm tim

Siêu âm tim là phương tiện chẩn đoán phổ biến, có thể thực hiện tại giường của người bệnh. Siêu âm tim có chất lượng cao cần được thực hiện bởi chuyên gia về tăng áp phổi để giảm thiểu sai số giữa các lần đo. Lưu ý là áp lực động mạch phổi tâm thu đo lúc nghỉ không có giá trị tiên lượng và không được dùng để ra quyết định điều trị.

Đánh giá rối loạn chức năng thất phải dựa vào việc đo thay đổi của phân suất diện tích, di động tâm thu của mặt phẳng vòng van ba lá (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion – TAPSE), Doppler mô và siêu âm tim đánh dấu mô cơ tim 2D thành tự do thất phải. Đo kích thước buồng tim phải và tĩnh mạch chủ dưới. Phân độ tràn dịch màng tim và hở van ba lá. Đo tỉ số TAPSE/áp lực động mạch phổi tâm thu. Tỉ số này có liên quan chặt chẽ với sự kết nối thất phải-động mạch phổi và cho phép dự báo tiên lượng.

- Hình ảnh cộng hưởng từ tim

Thể tích thất phải, phân suất tống máu thất phải (right ventricular ejection fraction – RVEF) và chỉ số thể tích nhát bóp (stroke volume index – SVI) đo bằng hình ảnh cộng hưởng từ tim là những yếu tố tiên lượng quan trọng trong TAĐMP. Ở bệnh nhân TAĐMP, các số đo bằng hình ảnh cộng hưởng từ ban đầu bổ sung giá trị tiên lượng vào điểm nguy cơ. Ngoài ra, đánh giá nguy cơ sau 1 năm theo dõi dựa vào hình ảnh cộng hưởng từ tim có giá trị ít nhất là tương đương với đánh giá nguy cơ dựa vào thông tim phải. Các thông số đo bằng cộng hưởng từ tim được nêu trên Bảng 6.2. Điểm cắt của SVI được xác định dựa trên đồng thuận, một mức thay đổi 10 ml của thể tích nhát bóp trong quá trình theo dõi được xem là có ý nghĩa về mặt lâm sàng.

6.2.3. Khảo sát huyết động

Khảo sát huyết động bằng thông tim phải cung cấp thông tin quan trọng cho việc tiên lượng, cả vào thời điểm chẩn đoán lẫn trong quá trình theo dõi. Các thông số huyết động giúp đánh giá tiên lượng gồm áp lực nhĩ phải, chỉ số tim, SVI và độ bão hòa oxy máu tĩnh mạch trộn (SvO2) (Bảng 6.2). Một số trung tâm thực hiện thông tim phải thường xuyên trong quá trình theo dõi, tuy nhiên một số trung tâm khác chỉ thực hiện nghiệm pháp này khi có chỉ định về mặt lâm sàng. Hiện không có chứng cứ cho thấy cách tiếp cận nào tốt hơn (Bảng 6.3).

6.2.4. Khả năng gắng sức

Nghiệm pháp đi bộ 6 phút (6-minute walking test – 6MWT) là biện pháp thường được dùng nhất để đánh giá khả năng gắng sức của bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi. Nghiệm pháp này dễ thực hiện, không tốn kém, được chấp nhận rộng rãi bởi bệnh nhân, nhân viên y tế và các cơ sở y tế như một biện pháp quan trọng và có giá trị được khẳng định trong đánh giá tăng áp phổi. Thay đổi 6MWT là một trong các thông số thường được dùng nhất trong các thử nghiệm lâm sàng trên bệnh nhân TAĐMP, được dùng như tiêu chí đánh giá chính, tiêu chí đánh giá phụ hoặc thành phần của kết cục xấu đi về mặt lâm sàng. Sự cải thiện của 6MWT ít có giá trị dự báo hơn so với sự xấu đi của nghiệm pháp này.

Nghiệm pháp gắng sức tim phổi là một phương pháp không xâm lấn đánh giá khả năng chức năng và sự hạn chế gắng sức. Mức hấp thụ oxy đỉnh và VE/VCO2 có giá trị tiên lượng mạnh. Tuy nhiên giá trị bổ sung của nghiệm pháp gắng sức tim phổi trên nền của các thông số lâm sàng và huyết động thường dùng vẫn chưa được khảo sát kỹ.

6.2.5. Các chỉ dấu sinh hóa

BNP và NT-proBNP là các chỉ dấu sinh hóa được dùng thường quy trong thực hành lâm sàng tại các trung tâm chăm sóc bệnh nhân tăng áp phổi. BNP và NT-proBNP không đặc hiệu cho tăng áp phổi. Các điểm cắt giúp phân tầng nguy cơ được nêu trên Bảng 6.2 và

Bảng 6.4

Thời điểm thực hiện các khảo sát lâm sàng, cận lâm sàng được nêu trên Bảng 6.3.

6.2.6. Số đo kết cục do người bệnh báo cáo

Số đo kết cục do người bệnh báo cáo (patient-reported outcome measure – PROM) là một thuật ngữ về kết cục sức khỏe do người bệnh tự báo cáo. Đó là trải nghiệm của người bệnh sống với tăng áp phổi và ảnh hưởng của nó trên người bệnh và những người chăm sóc. Mặc dù đã có nhiều tiến bộ trong điều trị TAĐMP, bệnh nhân TAĐMP vẫn bị nhiều triệu chứng dù không đặc hiệu nhưng gây suy yếu và suy giảm chất lượng sống. Một số PROM đặc hiệu cho tăng áp phổi đã được phát triển, giúp theo dõi tình trạng chức năng, sự xấu đi về mặt lâm sàng và tiên lượng của người bệnh TAĐMP: Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR), emPHasis 10, Living with Pulmonary Hypertension và Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension-Symptoms and Impact (PAH-SYMPACT).

6.2.7. Đánh giá một cách toàn diện tiên lượng, nguy cơ và các mục tiêu điều trị

Phân tầng nguy cơ giúp xác định mức độ nặng của bệnh và đánh giá xem bệnh nhân cải thiện, ổn định hay xấu đi trong quá trình theo dõi. Nhiều nghiên cứu đã chứng minh là đạt được tình trạng nguy cơ thấp trong quá trình điều trị sẽ cải thiện tiên lượng của bệnh nhân, do vậy phân tầng nguy cơ giúp hướng dẫn điều trị.

Vào thời điểm chẩn đoán, dùng mô hình 3 mức để phân tầng nguy cơ (Bảng 6.2), trong đó đặc biệt chú ý đến WHO-FC, 6MWT, BNP/NT-proBNP và các thông số huyết động. Trong quá trình theo dõi, dùng mô hình 4 mức để phân tầng nguy cơ (Bảng 6.4), tuy nhiên cũng nên xem xét thực hiện các nghiệm pháp cận lâm sàng bổ sung nếu cần, đặc biệt là hình ảnh học tim phải và khảo sát huyết động. Ở mọi giai đoạn, nên xem xét các yếu tố cá nhân như tuổi, giới, thể bệnh, bệnh đồng mắc và chức năng thận.

Các khuyến cáo về đánh giá độ nặng của bệnh và nguy cơ tử vong của bệnh nhân TAĐMP được nêu trên Bảng 6.5.

Bảng 6.2 Phân tầng nguy cơ bệnh nhân tăng áp động mạch phổi vào thời điểm chẩn đoán

| Yếu tố xác định tiên lượng

(tử vong ước tính sau 1 năm) |

Nguy cơ thấp

<5% |

Nguy cơ trung gian

5-20% |

Nguy cơ cao

>20% |

| Dấu hiệu lâm sàng của suy thất phải | Không | Không | Có |

| Tiến triển của các triệu chứng và biểu hiện lâm sàng | Không | Chậm | Nhanh |

| Ngất | Không | Ngất thỉnh thoảng* | Ngất lặp lại** |

| Độ chức năng theo WHO | I, II | III | IV |

| Nghiệm pháp đi bộ 6 phút | >440 m | 165-440 m | <165 m |

| Nghiệm pháp gắng sức tim phổi | Peak VO2 >15 mL/min/kg (>65% dự báo)

VE/VCO2 <36 |

Peak VO2 11-15 mL/min/kg (35-65% dự báo)

VE/VCO2 36-44 |

Peak VO2 <11 mL/min/kg (<35% dự báo)

VE/VCO2 >44 |

| BNP hoặc NT-proBNP | BNP <50 ng/L

NT-proBNP <300 ng/L |

BNP 50-800 ng/L

NT-proBNP 300- 1100 ng/L |

BNP >800 ng/L

NT-proBNP >1100 ng/L |

| Siêu âm tim | DTNP <18 cm2

TAPSE/sPAP >0,32 mm/mmHg Không TDMT |

DTNP 18-26 cm2

TAPSE/sPAP 0,19-0,32 mm/mmHg TDMT lượng ít |

DTNP >26 cm2

TAPSE/sPAP <0,19 mm/mmHg TDMT trung bình, nhiều |

| Cộng hưởng từ tim | RVEF >54%

SVI > 40 mL/m2 RVESVI <42 ml/m2 |

RVEF 37-54%

SVI 26- 40 mL/m2 RVESVI 42-54 ml/m2 |

RVEF <37%

SVI <26 mL/m2 RVESVI >54 ml/m2 |

| Khảo sát huyết động | ALNP <8 mmHg

CI ≥2,5 L/ph/m2 SVI >38 mL/m2 SvO2 >65% |

ALNP 8-14 mmHg

CI 2-2,4 L/ph/m2 SVI 31-38 mL/m2 SvO2 60-65% |

ALNP >14 mmHg

CI <2 L/ph/m2 SVI <31 ml/m2 SvO2 <60% |

*Ngất thỉnh thoảng khi gắng sức nặng hoặc ở tư thế đứng ở người bệnh ổn định.

**Ngất lặp lại ngay cả khi hoạt động thể lực nhẹ hoặc thông thường.

ALNP: áp lực nhĩ phải; CI: chỉ số tim; DTNP: diện tích nhĩ phải; RVEF: phân suất tống máu thất phải; RVESVI: chỉ số thể tích cuối tâm thu thất phải; sPAP: áp lực động mạch phổi tâm thu; SVI: chỉ số thể tích nhát bóp; SvO2: độ bão hòa oxy máu tĩnh mạch trộn; TAPSE: di động tâm thu của mặt phẳng vòng van 3 lá; TDMT: tràn dịch màng tim.

Bảng 6.3 Thời điểm thực hiện các khảo sát lâm sàng và cận lâm sàng ở bệnh nhân tăng áp động mạch phổi

| Ban đầu | 3-6 tháng sau thay đổi điều trị | Mỗi 3-6 tháng ở bệnh nhân ổn định | Khi tình trạng lâm sàng xấu đi | |

| Đánh giá y khoa (bao gồm WHO-FC) | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 6MWT | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Xét nghiệm máu (bao gồm NT-proBNP) | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Điện tim | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Siêu âm tim hoặc hình ảnh cộng hưởng từ tim | +++ | +++ | + | +++ |

| Khí máu động mạch hoặc SpO2 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Chất lượng sống đặc hiệu với bệnh | + | + | + | + |

| Nghiệm pháp gắng sức tim phổi | + | + | + | + |

| Thông tim phải | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

+++: được chỉ định; ++: nên được xem xét; +: có thể được cân nhắc

Bảng 6.4 Các thông số dùng để phân tầng nguy cơ thành 4 mức

| Yếu tố xác định tiên lượng | Nguy cơ thấp | Nguy cơ

trung bình – thấp |

Nguy cơ

trung bình – cao |

Nguy cơ cao |

| Điểm | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Độ chức năng theo WHO | I hoặc II* | – | III | IV |

| Nghiệm pháp đi bộ 6 phút (m) | >440 | 320-440 | 165-319 | <165 |

| BNP hoặc

NT-proBNP |

<50

<300 |

50-199

300-649 |

200-800

650-1100 |

>800

>1100 |

Tính mức nguy cơ bằng cách chia tổng điểm cho số biến và làm tròn đến số nguyên lớn hơn.

*Độ chức năng theo WHO I và II đều được tính 1 điểm vì cả 2 độ này đều có sống còn dài hạn tốt

Bảng 6.5 Các khuyến cáo về đánh giá độ nặng của bệnh và nguy cơ tử vong của bệnh nhân tăng áp động mạch phổi

| Khuyến cáo | Loại | MCC |

| Khuyến cáo đánh giá mức độ nặng của bệnh ở bệnh nhân TAĐMP bằng một bộ dữ liệu có được từ khám lâm sàng, nghiệm pháp gắng sức, chỉ dấu sinh hóa, siêu âm tim và khảo sát huyết động | I | B |

| Đạt được và duy trì một tình trạng nguy cơ thấp dựa trên điều trị nội khoa tối ưu được khuyến cáo như một mục tiêu điều trị ở bệnh nhân TAĐMP | I | B |

| Để phân tầng nguy cơ vào thời điểm chẩn đoán, việc dùng mô hình 3 mức (nguy cơ thấp, trung gian và cao) có tính đến tất cả các dữ liệu thu thập được, bao gồm khảo sát huyết động, được khuyến cáo | I | B |

| Để phân tầng nguy cơ trong quá trình theo dõi, việc dùng mô hình 4 mức (nguy cơ thấp, trung gian-thấp, trung gian-cao và cao) dựa trên WHO-FC, 6MWT và BNP/NT-proBNP, có tính đến các thông số bổ sung nếu cần, được khuyến cáo | I | B |

| Trong một số bệnh căn TAĐMP và ở một số bệnh nhân TAĐMP với bệnh đồng mắc, việc tối ưu hóa điều trị nên được xem xét dựa trên nền tảng cá thể hóa, đồng thời phải thừa nhận là không phải lúc nào cũng có thể đạt được tình trạng nguy cơ thấp | IIa | B |

(Vui lòng xem tiếp trong kỳ sau)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

- Rosenkranz S, Gibbs JS, Wachter R, De Marco T, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Vachiery JL. Left ventricular heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2016;37: 942–954.

- Maron BA, Brittain EL, Hess E, Waldo SW, Baron AE, Huang S, et al. Pulmonary vascular resistance and clinical outcomes in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:873–884.

- Bermejo J, Gonzalez-Mansilla A, Mombiela T, Fernandez AI, Martinez-Legazpi P, Yotti R, et al. Persistent pulmonary hypertension in corrected valvular heart disease:hemodynamic insights and long-term survival. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e019949.

- Caravita S, Dewachter C, Soranna D, D’Araujo SC, Khaldi A, Zambon A, et al. Haemodynamics to predict outcome in pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1702427.

- Crawford TC, Leary PJ, Fraser CD III, Suarez-Pierre A, Magruder JT, Baumgartner WA, et al. Impact of the new pulmonary hypertension definition on heart transplant outcomes: expanding the hemodynamic risk profile. Chest 2020;157:151–161.

- O’Sullivan CJ, Wenaweser P, Ceylan O, Rat-Wirtzler J, Stortecky S, Heg D, et al. Effect of pulmonary hypertension hemodynamic presentation on clinical outcomes in patients with severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: insights from the new proposed pulmonary hypertension classification. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:e002358.

- Vanderpool RR, Saul M, Nouraie M, Gladwin MT, Simon MA. Association between hemodynamic markers of pulmonary hypertension and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:298–306.

- Dreyfus GD, Martin RP, Chan KM, Dulguerov F, Alexandrescu C. Functional tricuspid regurgitation: a need to revise our understanding. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2331–2336.

- Muraru D, Parati G, Badano L. The importance and the challenges of predicting the progression of functional tricuspid regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:1652–1654.

- Andersen MJ, Hwang SJ, Kane GC, Melenovsky V, Olson TP, Fetterly K, et al. Enhanced pulmonary vasodilator reserve and abnormal right ventricular: pulmonary artery coupling in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:542–550.

- Tedford RJ, Hassoun PM, Mathai SC, Girgis RE, Russell SD, Thiemann DR, et al. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure augments right ventricular pulsatile loading. Circulation 2012;125:289–297.

- Bosch L, Lam CSP, Gong L, Chan SP, Sim D, Yeo D, et al. Right ventricular dysfunction in left-sided heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:1664–1671.

- Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Pislaru S, Borlaug BA. Deterioration in right ventricular structure and function over time in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2019;40:689–697.

- Kovacs G, Berghold A, Scheidl S, Olschewski H. Pulmonary arterial pressure during rest and exercise in healthy subjects: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2009;34: 888–894.

- D’Alto M, Romeo E, Argiento P, Pavelescu A, Melot C, D’Andrea A, et al. Echocardiographic prediction of pre- versus postcapillary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:108–115.

- D’Alto M, Romeo E, Argiento P, Pavelescu A, D’Andrea A, Di Marco GM, et al. A simple echocardiographic score for the diagnosis of pulmonary vascular disease in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Med 2017;18:237–243.

- Vachiery JL, Tedford RJ, Rosenkranz S, Palazzini M, Lang I, Guazzi M, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801897.

- Ho JE, Zern EK, Lau ES, Wooster L, Bailey CS, Cunningham T, et al. Exercise pulmonary hypertension predicts clinical outcomes in patients with dyspnea on effort. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:17–26.

- Eisman AS, Shah RV, Dhakal BP, Pappagianopoulos PP, Wooster L, Bailey C, et al. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure patterns during exercise predict exercise capacity and incident heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2018;11:e004750.

- Andersen MJ, Ersboll M, Bro-Jeppesen J, Gustafsson F, Hassager C, Kober L, et al. Exercise hemodynamics in patients with and without diastolic dysfunction and preserved ejection fraction after myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:444–451.

- Andersen MJ, Olson TP, Melenovsky V, Kane GC, Borlaug BA. Differential hemodynamic effects of exercise and volume expansion in people with and without heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:41–48.

- Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:588–595.

- Fujimoto N, Borlaug BA, Lewis GD, Hastings JL, Shafer KM, Bhella PS, et al. Hemodynamic responses to rapid saline loading: the impact of age, sex, and heart failure. Circulation 2013;127:55–62.

- Ho JE, Zern EK, Wooster L, Bailey CS, Cunningham T, Eisman AS, et al. Differential clinical profiles, exercise responses, and outcomes associated with existing HfpEF definitions. Circulation 2019;140:353–365.

- Baratto C, Caravita S, Soranna D, Faini A, Dewachter C, Zambon A, et al. Current limitations of invasive exercise hemodynamics for the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2021;14:e007555.

- Fox BD, Shimony A, Langleben D, Hirsch A, Rudski L, Schlesinger R, et al. High prevalence of occult left heart disease in scleroderma-pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2013;42:1083–1091.

- Lewis GD, Bossone E, Naeije R, Grunig E, Saggar R, Lancellotti P, et al. Pulmonary vascular hemodynamic response to exercise in cardiopulmonary diseases. Circulation 2013;128:1470–1479.

- Maor E, Grossman Y, Balmor RG, Segel M, Fefer P, Ben-Zekry S, et al. Exercise haemodynamics may unmask the diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction among patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:151–158.

- Robbins IM, Hemnes AR, Pugh ME, Brittain EL, Zhao DX, Piana RN, et al. High prevalence of occult pulmonary venous hypertension revealed by fluid challenge in pulmonary hypertension. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:116–122.

- Borlaug BA. Invasive assessment of pulmonary hypertension: time for a more fluid approach? Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:2–4.

- D’Alto M, Romeo E, Argiento P, Motoji Y, Correra A, Di Marco GM, et al. Clinical relevance of fluid challenge in patients evaluated for pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2017;151:119–126.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Bohm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–3726.

- Selim AM, Wadhwani L, Burdorf A, Raichlin E, Lowes B, Zolty R. Left ventricular assist devices in pulmonary hypertension group 2 with significantly elevated pulmonary vascular resistance: a bridge to cure. Heart Lung Circ 2019;28:946–952.

- Al-Kindi SG, Farhoud M, Zacharias M, Ginwalla MB, ElAmm CA, Benatti RD, et al. Left ventricular assist devices or inotropes for decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with pulmonary hypertension listed for heart transplantation. J Card Fail 2017;23:209–215.

- Imamura T, Chung B, Nguyen A, Rodgers D, Sayer G, Adatya S, et al. Decoupling between diastolic pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure as a prognostic factor after continuous flow ventricular assist device implantation. Circ Heart Fail 2017;10:e003882.

- Kaluski E, Cotter G, Leitman M, Milo-Cotter O, Krakover R, Kobrin I, et al. Clinical and hemodynamic effects of bosentan dose optimization in symptomatic heart failure patients with severe systolic dysfunction, associated with secondary pulmonary hypertension–a multi-center randomized study. Cardiology 2008;109:273–280.

- Lewis GD, Shah R, Shahzad K, Camuso JM, Pappagianopoulos PP, Hung J, et al. Sildenafil improves exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with systolic heart failure and secondary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2007;116:1555–1562.

- Dumitrescu D, Seck C, Mohle L, Erdmann E, Rosenkranz S. Therapeutic potential of sildenafil in patients with heart failure and reactive pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2012;154:205–206.

- Wu X, Yang T, Zhou Q, Li S, Huang L. Additional use of a phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor in patients with pulmonary hypertension secondary to chronic systolic heart failure: a meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:444–453.

- Koller B, Steringer-Mascherbauer R, Ebner CH, Weber T, Ammer M, Eichinger J, et al. Pilot study of endothelin receptor blockade in heart failure with diastolic dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension (BADDHY-trial). Heart Lung Circ 2017;26:433–441.

- Vachiery JL, Delcroix M, Al-Hiti H, Efficace M, Hutyra M, Lack G, et al. Macitentan in pulmonary hypertension due to left ventricular dysfunction. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1701886.

- Hoendermis ES, Liu LC, Hummel YM, van der Meer P, de Boer RA, Berger RM, et al. Effects of sildenafil on invasive haemodynamics and exercise capacity in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction and pulmonary hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2565–2573.

- Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation 2011;124:164–174.

- Opitz CF, Hoeper MM, Gibbs JS, Kaemmerer H, Pepke-Zaba J, Coghlan JG, et al. Pre-capillary, combined, and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension: a pathophysiological continuum. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:368–378.

- Kramer T, Dumitrescu D, Gerhardt F, Orlova K, Ten Freyhaus H, Hellmich M, et al. Therapeutic potential of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and combined post- and pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2019;283:152–158.

- Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Shah SJ, Kaye DM, Gustafsson F, Hasenfubeta G, et al. Effects of interatrial shunt on pulmonary vascular function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2539–2550.

- Shah SJ, Borlaug BA, Chung ES, Cutlip DE, Debonnaire P, Fail PS, et al. Atrial shunt device for heart failure with preserved and mildly reduced ejection fraction (REDUCE LAP-HF II): a randomised, multicentre, blinded, sham-controlled trial. Lancet 2022;399:1130–1140.

- Borlaug BA, Blair J, Bergmann MW, Bugger H, Burkhoff D, Bruch L, et al. Latent pulmonary vascular disease may alter the response to therapeutic atrial shunt device in heart failure. Circulation 2022;145:1592–1604.

- Gaemperli O, Moccetti M, Surder D, Biaggi P, Hurlimann D, Kretschmar O, et al. Acute haemodynamic changes after percutaneous mitral valve repair: relation to mid-term outcomes. Heart 2012;98:126–132.

- Tigges E, Blankenberg S, von Bardeleben RS, Zurn C, Bekeredjian R, Ouarrak T, et al. Implication of pulmonary hypertension in patients undergoing MitraClip therapy: results from the German transcatheter mitral valve interventions (TRAMI) registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:585–594.

- Zlotnick DM, Ouellette ML, Malenka DJ, DeSimone JP, Leavitt BJ, Helm RE, et al. Effect of preoperative pulmonary hypertension on outcomes in patients with severe aortic stenosis following surgical aortic valve replacement. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:1635–1640.

- Melby SJ, Moon MR, Lindman BR, Bailey MS, Hill LL, Damiano RJ Jr. Impact of pulmonary hypertension on outcomes after aortic valve replacement for aortic valve stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:1424–1430.

- Lucon A, Oger E, Bedossa M, Boulmier D, Verhoye JP, Eltchaninoff H, et al. Prognostic implications of pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: study from the FRANCE 2 Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:240–247.

- Faggiano P, Antonini-Canterin F, Ribichini F, D’Aloia A, Ferrero V, Cervesato E, et al. Pulmonary artery hypertension in adult patients with symptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2000;85:204–208.

- Zuern CS, Eick C, Rizas K, Stoleriu C, Woernle B, Wildhirt S, et al. Prognostic value of mild-to-moderate pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis undergoing aortic valve replacement. Clin Res Cardiol 2012;101:81–88.

- Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P, Gauducheau E, de Vincentiis C, Baudet E, et al. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;15:816–822; discussion 822–813.

- Bermejo J, Yotti R, Garcia-Orta R, Sanchez-Fernandez PL, Castano M, Segovia-Cubero J, et al. Sildenafil for improving outcomes in patients with corrected valvular heart disease and persistent pulmonary hypertension: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1255–1264.

- Chorin E, Rozenbaum Z, Topilsky Y, Konigstein M, Ziv-Baran T, Richert E, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and long-term clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;21:157–165.

- Topilsky Y, Nkomo VT, Vatury O, Michelena HI, Letourneau T, Suri RM, et al. Clinical outcome of isolated tricuspid regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:1185–1194.

- Lurz P, Orban M, Besler C, Braun D, Schlotter F, Noack T, et al. Clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and risk stratification of pulmonary hypertension in severe tricuspid regurgitation and implications for transcatheter tricuspid valve repair. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2785–2795.

- Brener MI, Lurz P, Hausleiter J, Rodes-Cabau J, Fam N, Kodali SK, et al. Right ventricular-pulmonary arterial coupling and afterload reserve in patients undergoing transcatheter tricuspid valve repair. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:448–461

- Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801913.

- Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J 2015;46:903–975.

- Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37:67–119.

- Certain MC, Chaumais MC, Jais X, Savale L, Seferian A, Parent F, et al. Characteristics and long-term outcomes of pulmonary venoocclusive disease in- duced by mitomycin C. Chest 2021;159:1197–1207.

- Montani D, Lau EM, Descatha A, Jais X, Savale L, Andujar P, et al. Occupational ex- posure to organic solvents: a risk factor for pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1721–1731.

- Weatherald J, Bondeelle L, Chaumais MC, Guignabert C, Savale L, Jais X, et al. Pulmonary complications of Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Eur Respir J 2020; 56:2000279.

- Hurdman J, Condliffe R, Elliot CA, Swift A, Rajaram S, Davies C, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in COPD: results from the ASPIRE registry. Eur Respir J 2013;41: 1292–1301.

- Delcroix M, Torbicki A, Gopalan D, Sitbon O, Klok FA, Lang I, et al. ERS statement on chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2020;57: 2002828.

- Shlobin OA, Kouranos V, Barnett SD, Alhamad EH, Culver DA, Barney J, et al. Physiological predictors of survival in patients with sarcoidosis-associated pulmon- ary hypertension: results from an international registry. Eur Respir J 2020;55: 1901747.

- Arcasoy SM, Christie JD, Ferrari VA, Sutton MS, Zisman DA, Blumenthal NP, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with ad- vanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:735–740.

- Fisher MR, Forfia PR, Chamera E, Housten-Harris T, Champion HC, Girgis RE, et al. Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of pul- monary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:615–621

- Fonseca GH, Souza R, Salemi VM, Jardim CV, Gualandro SF. Pulmonary hyperten- sion diagnosed by right heart catheterisation in sickle cell disease. Eur Respir J 2012; 39:112–118.

- Parent F, Bachir D, Inamo J, Lionnet F, Driss F, Loko G, et al. A hemodynamic study of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 2011;365:44–53.

- Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, Budts W, Chessa M, Diller GP, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 2021;42:563–645.

- Kim NH, Delcroix M, Jais X, Madani MM, Matsubara H, Mayer E, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801915.

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, Fauueno H, Bueno H, Geersing GJ, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary em- bolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2020;41:543–603.

- Swift AJ, Dwivedi K, Johns C, Garg P, Chin M, Currie BJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CT pulmonary angiography in suspected pulmonary hypertension. Eur Radiol 2020; 30:4918–4929.

- Guerin L, Couturaud F, Parent F, Revel MP, Gillaizeau F, Planquette B, et al. Prevalence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pul- monary embolism. Prevalence of CTEPH after pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost 2014;112:598–605.

- Boerrigter BG, Bogaard HJ, Trip P, Groepenhoff H, Rietema H, Holverda S, et al. Ventilatory and cardiocirculatory exercise profiles in COPD: the role of pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2012;142:1166–1174.

- Guth S, Wiedenroth CB, Rieth A, Richter MJ, Gruenig E, Ghofrani HA, et al. Exercise right heart catheterization before and after pulmonary endarterectomy in patients with chronic thromboembolic disease. Eur Respir J 2018;52:1800458.

- Eyries M, Montani D, Girerd B, Perret C, Leroy A, Lonjou C, et al. EIF2AK4 muta- tions cause pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, a recessive form of pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet 2014;46:65–69.

- Cottin V, Le Pavec J, Prevot G, Mal H, Humbert M, Simonneau G, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syn- drome. Eur Respir J 2010;35:105–111.

- Sitbon O, Bosch J, Cottreel E, Csonka D, de Groote P, Hoeper MM, et al. Macitentan for the treatment of portopulmonary hypertension (PORTICO): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 4 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:594–604.

- Armstrong I, Billings C, Kiely DG, Yorke J, Harries C, Clayton S, et al. The patient experience of pulmonary hypertension: a large cross-sectional study of UK pa- tients. BMC Pulm Med 2019;19:67.

- Coghlan JG, Denton CP, Grunig E, Bonderman D, Distler O, Khanna D, et al. Evidence-based detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: the DETECT study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1340–1349.

- Krowka MJ, Fallon MB, Kawut SM, Fuhrmann V, Heimbach JK, Ramsay MA, et al. International Liver Transplant Society Practice Guidelines: diagnosis and manage- ment of hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension. Transplantation 2016;100:1440–1452.

- Sitbon O, Lascoux-Combe C, Delfraissy JF, Yeni PG, Raffi F, De Zuttere D, et al. Prevalence of HIV-related pulmonary arterial hypertension in the current anti- retroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:108–113.

- Nathan SD, Behr J, Collard HR, Cottin V, Hoeper MM, Martinez FJ, et al. Riociguat for idiopathic interstitial pneumonia-associated pulmonary hypertension (RISE-IIP): a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b study. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7: 780–790.

- Helmersen D, Provencher S, Hirsch AM, Van Dam A, Dennie C, de Perrot M, et al. Diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: A Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline update. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med 2019;3:177–198.

- Humbert M, Farber HW, Ghofrani HA, Benza RL, Busse D, Meier C, et al. Risk as- sessment in pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pul- monary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1802004.

- Kuwana M, Blair C, Takahashi T, Langley J, Coghlan JG. Initial combination therapy of ambrisentan and tadalafil in connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary ar- terial hypertension (CTD-PAH) in the modified intention-to-treat population of the AMBITION study: post hoc analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:626–634.

- Olsson KM, Delcroix M, Ghofrani HA, Tiede H, Huscher D, Speich R, et al. Anticoagulation and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA). Circulation 2014;129:57–65.

- Montani D, Savale L, Natali D, Jais X, Herve P, Garcia G, et al. Long-term response to calcium-channel blockers in non-idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1898–1907.

- Badesch DB, Tapson VF, McGoon MD, Brundage BH, Rubin LJ, Wigley FM, et al. Continuous intravenous epoprostenol for pulmonary hypertension due to the scleroderma spectrum of disease. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:425–434.

- Nunes H, Humbert M, Sitbon O, Morse JH, Deng Z, Knowles JA, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in human immunodeficiency virus-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1433–1439.

- Montani D, Lau EM, Dorfmuller P, Girerd B, Jais X, Savale L, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2016;47:1518–1534.

- Chin KM, Channick RN, Rubin LJ. Is methamphetamine use associated with idio- pathic pulmonary arterial hypertension? Chest 2006;130:1657–1663.

- Zamanian RT, Hedlin H, Greuenwald P, Wilson DM, Segal JI, Jorden M, et al. Features and outcomes of methamphetamine-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197:788–800.

- Savale L, Sattler C, Gunther S, Montani D, Chaumais MC, Perrin S, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients treated with interferon. Eur Respir J 2014;44: 1627–1634.

- Weatherald J, Chaumais MC, Savale L, Jais X, Seferian A, Canuet M, et al. Long-term outcomes of dasatinib-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension: a population- based study. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1700217.

- Cardio-Oncology: Lyon AR, López-Fernández T, Couch LS, Asteggiano R, Aznar MC, Bergler-Klein J, et al. Guidelines on cardio-oncology. Eur Heart J. 2022. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac244.

- Avouac J, Airo P, Meune C, Beretta L, Dieude P, Caramaschi P, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis in European Caucasians and metaa- nalysis of 5 studies. J Rheumatol 2010;37:2290–2298.

- Launay D, Montani D, Hassoun PM, Cottin V, Le Pavec J, Clerson P, et al. Clinical phenotypes and survival of pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension in systemic scler- osis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0197112.

- Launay D, Sobanski V, Hachulla E, Humbert M. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis: different phenotypes. Eur Respir Rev 2017;26:170056.

- Hachulla E, Jais X, Cinquetti G, Clerson P, Rottat L, Launay D, et al. Pulmonary ar- terial hypertension associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry. Chest 2018;153:143–151.

- Jais X, Launay D, Yaici A, Le Pavec J, Tcherakian C, Sitbon O, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus- and mixed connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a retrospective analysis of twenty-three cases. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:521–531.

- Qian J, Li M, Zhang X, Wang Q, Zhao J, Tian Z, et al. Long-term prognosis of pa- tients with systemic lupus erythematosus-associated pulmonary arterial hyperten- sion: CSTAR-PAH cohort study. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1800081.

- Sanges S, Yelnik CM, Sitbon O, Benveniste O, Mariampillai K, Phillips-Houlbracq M, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: data from the French pulmonary hypertension registry and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4911.

- Wang J, Li M, Wang Q, Zhang X, Qian J, Zhao J, et al. Pulmonary arterial hyperten- sion associated with primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a multicentre cohort study from China. Eur Respir J 2020;56:1902157.

- Montani D, Henry J, O’Connell C, Jais X, Cottin V, Launay D, et al. Association be- tween rheumatoid arthritis and pulmonary hypertension: data from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry. Respiration 2018;95:244–250.

- Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1023–1030.

- Humbert M, Khaltaev N, Bousquet J, Souza R. Pulmonary hypertension: from an orphan disease to a public health problem. Chest 2007;132:365–367.

- Gunther S, Jais X, Maitre S, Berezne A, Dorfmuller P, Seferian A, et al. Computed tomography findings of pulmonary venoocclusive disease in scleroderma patients presenting with precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64: 2995–3005.

- Hsu S, Kokkonen-Simon KM, Kirk JA, Kolb TM, Damico RL, Mathai SC, et al. Right ventricular myofilament functional differences in humans with systemic sclerosis-associated versus idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2018;137:2360–2370.

- Chauvelot L, Gamondes D, Berthiller J, Nieves A, Renard S, Catella-Chatron J, et al. Hemodynamic response to treatment and outcomes in pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease versus pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: data from a study identifying prognostic factors in pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 2021;73: 295–304.

- Launay D, Sitbon O, Hachulla E, Mouthon L, Gressin V, Rottat L, et al. Survival in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern man- agement era. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1940–1946.

- Ramjug S, Hussain N, Hurdman J, Billings C, Charalampopoulos A, Elliot CA, et al.Idiopathic and systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a comparison of demographic, hemodynamic, and MRI characteristics and outcomes. Chest 2017;152:92–102.

- Pan J, Lei L, Zhao C. Comparison between the efficacy of combination therapy and monotherapy in connective tissue disease associated pulmonary arterial hyperten- sion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2018;36: 1095–1102.

- Sanchez O, Sitbon O, Jais X, Simonneau G, Humbert M. Immunosuppressive therapy in connective tissue diseases-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2006;130:182–189.

- Humbert M, Coghlan JG, Ghofrani HA, Grimminger F, He JG, Riemekasten G, et al. Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue disease: results from PATENT-1 and PATENT-2. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:422–426.

- Kawut SM, Taichman DB, Archer-Chicko CL, Palevsky HI, Kimmel SE. Hemodynamics and survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension re- lated to systemic sclerosis. Chest 2003;123:344–350.

- Trombetta AC, Pizzorni C, Ruaro B, Paolino S, Sulli A, Smith V, et al. Effects of longterm treatment with bosentan and iloprost on nailfold absolute capillary number, fingertip blood perfusion, and clinical status in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2016; 43:2033–2041.

- Pradere P, Tudorache I, Magnusson J, Savale L, Brugiere O, Douvry B, et al. Lung transplantation for scleroderma lung disease: An international, multicenter, obser- vational cohort study. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37:903–911.

- Barbaro G, Lucchini A, Pellicelli AM, Grisorio B, Giancaspro G, Fauarbarini G, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy compared with HAART and bosentan in com- bination in patients with HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension. Heart 2006;92: 1164–1166.

- Degano B, Guillaume M, Savale L, Montani D, Jais X, Yaici A, et al. HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: survival and prognostic factors in the modern therapeutic era. AIDS 2010;24:67–75.

- Sitbon O. HIV-related pulmonary arterial hypertension: clinical presentation and management. AIDS 2008;22:S55–S62.

- Opravil M, Sereni D. Natural history of HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hyper- tension: trends in the HAART era. AIDS (London, England) 2008;22:S35–S40.

- Humbert M, Monti G, Fartoukh M, Magnan A, Brenot F, Rain B, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor expression in primary pulmonary hypertension: comparison of HIV seropositive and HIV seronegative patients. Eur Respir J 1998; 11:554–559.

- Mehta NJ, Khan IA, Mehta RN, Sepkowitz DA. HIV-related pulmonary hypertension: analytic review of 131 cases. Chest 2000;118:1133–1141.

- Zuber JP, Calmy A, Evison JM, Hasse B, Schiffer V, Wagels T, et al. Pulmonary ar- terial hypertension related to HIV infection: improved hemodynamics and survival associated with antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:1178–1185.

- Sitbon O, Gressin V, Speich R, Macdonald PS, Opravil M, Cooper DA, et al. Bosentan for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated pulmon- ary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:1212–1217.

- Degano B, Yaici A, Le Pavec J, Savale L, Jais X, Camara B, et al. Long-term effects of bosentan in patients with HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009;33:92–98.

- Carlsen J, Kjeldsen K, Gerstoft J. Sildenafil as a successful treatment of otherwise fatal HIV-related pulmonary hypertension. AIDS 2002;16:1568–1569.

- Schumacher YO, Zdebik A, Huonker M, Kreisel W. Sildenafil in HIV-related pulmonary hypertension. AIDS 2001;15:1747–1748.

- Muirhead GJ, Wulff MB, Fielding A, Kleinermans D, Buss N. Pharmacokinetic inter- actions between sildenafil and saquinavir/ritonavir. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2000;50: 99–107.

- Garraffo R, Lavrut T, Ferrando S, Durant J, Rouyrre N, MacGregor TR, et al. Effect of tipranavir/ritonavir combination on the pharmacokinetics of tadalafil in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2011;51:1071–1078.

- Aguilar RV, Farber HW. Epoprostenol (prostacyclin) therapy in HIV-associated pul- monary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1846–1850.

- Cea-Calvo L, Escribano Subias P, Tello de Menesses R, Lazaro Salvador M, Gomez Sanchez MA, Delgado Jimenez JF, et al. Treatment of HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension with treprostinil. Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56:421–425.

- Ghofrani HA, Friese G, Discher T, Olschewski H, Schermuly RT, Weissmann N, et al. Inhaled iloprost is a potent acute pulmonary vasodilator in HIV-related severe pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2004;23:321–326

- Krowka MJ, Miller DP, Barst RJ, Taichman D, Dweik RA, Badesch DB, et al. Portopulmonary hypertension: a report from the US-based REVEAL Registry. Chest 2012;141:906–915.

- Lazaro Salvador M, Quezada Loaiza CA, Rodriguez Padial L, Barbera JA, Lopez-Meseguer M, Lopez-Reyes R, et al. Portopulmonary hypertension: prognosis and management in the current treatment era – results from the REHAP registry. Intern Med J 2021;51:355–365.

- Savale L, Guimas M, Ebstein N, Fertin M, Jevnikar M, Renard S, et al. Portopulmonary hypertension in the current era of pulmonary hypertension man- agement. J Hepatol 2020;73:130–139.

- Baiges A, Turon F, Simon-Talero M, Tasayco S, Bueno J, Zekrini K, et al. Congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts (Abernethy malformation): an international ob- servational study. Hepatology 2020;71:658–669.

- Fussner LA, Iyer VN, Cartin-Ceba R, Lin G, Watt KD, Krowka MJ. Intrapulmonary vascular dilatations are common in portopulmonary hypertension and may be as- sociated with decreased survival. Liver Transpl 2015;21:1355–1364.

- Hoeper MM, Halank M, Marx C, Hoeffken G, Seyfarth HJ, Schauer J, et al. Bosentan therapy for portopulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2005;25:502–508.

- Olsson KM, Meyer K, Berliner D, Hoeper MM. Development of hepatopulmonary syndrome during combination therapy for portopulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801880.

- Krowka MJ, Plevak DJ, Findlay JY, Rosen CB, Wiesner RH, Krom RA. Pulmonary hemodynamics and perioperative cardiopulmonary-related mortality in patients with portopulmonary hypertension undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2000;6:443–450.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Burger C, Swanson K, Vargas H, Aqel B, Keaveny AP, et al. Clinical outcomes after liver transplantation in patients with portopulmonary hyperten- sion. Transplantation 2021;105:2283–2290.

- Deroo R, Trepo E, Holvoet T, De Pauw M, Geerts A, Verhelst X, et al. Vasomodulators and liver transplantation for portopulmonary hypertension: evi- dence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2020;72: 1701–1716.

- Sadd CJ, Osman F, Li Z, Chybowski A, Decker C, Henderson B, et al. Long-term outcomes and survival in moderate-severe portopulmonary hypertension after li- ver transplant. Transplantation 2021;105:346–353.

- Savale L, Sattler C, Coilly A, Conti F, Renard S, Francoz C, et al. Long-term outcome in liver transplantation candidates with portopulmonary hypertension. Hepatology 2017;65:1683–1692.

- Diller GP, Kempny A, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Swan L, Uebing A, Li W, et al. Survival prospects and circumstances of death in contemporary adult congenital heart dis- ease patients under follow-up at a large tertiary centre. Circulation 2015;132: 2118–2125.

- van Riel AC, Schuuring MJ, van Hessen ID, Zwinderman AH, Cozijnsen L, Reichert CL, et al. Contemporary prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in adult congenital heart disease following the updated clinical classification. Int J Cardiol 2014;174:299–305.

- Lammers AE, Bauer LJ, Diller GP, Helm PC, Abdul-Khaliq H, Bauer UMM, et al. Pulmonary hypertension after shunt closure in patients with simple congenital heart defects. Int J Cardiol 2020;308:28–32.

- Ntiloudi D, Zanos S, Gatzoulis MA, Karvounis H, Giannakoulas G. How to evaluate patients with congenital heart disease-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2019;17:11–18.

- Dimopoulos K, Condliffe R, Tulloh RMR, Clift P, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Bedair R, et al. Echocardiographic screening for pulmonary hypertension in congenital heart dis- ease: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2778–2788.

- Kempny A, Dimopoulos K, Fraisse A, Diller GP, Price LC, Rafiq I, et al. Blood vis- cosity and its relevance to the diagnosis and management of pulmonary hyperten- sion. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2640–2642.

- Arvanitaki A, Giannakoulas G, Baumgartner H, Lammers AE. Eisenmenger syn- drome: diagnosis, prognosis and clinical management. Heart 2020;106:1638–1645.

- Diller GP, Korten MA, Bauer UM, Miera O, Tutarel O, Kaemmerer H, et al. Current therapy and outcome of Eisenmenger syndrome: data of the German National Register for congenital heart defects. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1449–1455.

- Kempny A, Hjortshoj CS, Gu H, Li W, Opotowsky AR, Landzberg MJ, et al. Predictors of death in contemporary adult patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter study. Circulation 2017;135:1432–1440.

- Arvind B, Relan J, Kothari SS. “Treat and repair” strategy for shunt lesions: a critical review. Pulm Circ 2020;10:2045894020917885.

- Brida M, Nashat H, Gatzoulis MA. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: closing the gap in congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2020;26:422–428.

- van der Feen DE, Bartelds B, de Boer RA, Berger RMF. Assessment of reversibility in pulmonary arterial hypertension and congenital heart disease. Heart 2019;105: 276–282.

- Becker-Grunig T, Klose H, Ehlken N, Lichtblau M, Nagel C, Fischer C, et al. Efficacy of exercise training in pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:375–381.

- Hartopo AB, Anggrahini DW, Nurdiati DS, Emoto N, Dinarti LK. Severe pulmon- ary hypertension and reduced right ventricle systolic function associated with ma- ternal mortality in pregnant uncorrected congenital heart diseases. Pulm Circ 2019; 9:2045894019884516.

- Li Q, Dimopoulos K, Liu T, Xu Z, Liu Q, Li Y, et al. Peripartum outcomes in a large population of women with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with con- genital heart disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019;26:1067–1076.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Cifkova R, De Bonis M, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardio- vascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3165–3241.

- Blanche C, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Uribarri A, Kempny A, Swan L, Price L, et al. Use of intravenous iron in cyanotic patients with congenital heart disease and/or pulmon- ary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2018;267:79–83.

- Bertoletti L, Mismetti V, Giannakoulas G. Use of anticoagulants in patients with pul- monary hypertension. Hamostaseologie 2020;40:348–355.

- Freisinger E, Gerss J, Makowski L, Marschall U, Reinecke H, Baumgartner H, et al. Current use and safety of novel oral anticoagulants in adults with congenital heart disease: results of a nationwide analysis including more than 44 000 patients. Eur Heart J 2020;41:4168–4177.

- Galiè N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis MA, Granton J, Berger RM, Lauer A, et al. Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double-blind, ran- domized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation 2006;114:48–54.

- Gatzoulis MA, Landzberg M, Beghetti M, Berger RM, Efficace M, Gesang S, et al. Evaluation of Macitentan in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. Circulation 2019;139:51–63.

- Zuckerman WA, Leaderer D, Rowan CA, Mituniewicz JD, Rosenzweig EB. Ambrisentan for pulmonary arterial hypertension due to congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:1381–1385.

- Nashat H, Kempny A, Harries C, Dormand N, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Price LC, et al. A single-centre, placebo-controlled, double-blind randomised cross-over study of nebulised iloprost in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: A pilot study. Int J Cardiol 2020;299:131–135.

- D’Alto M, Constantine A, Balint OH, Romeo E, Argiento P, Ablonczy L, et al. The effects of parenteral prostacyclin therapy as add-on treatment to oral compounds in Eisenmenger syndrome. Eur Respir J 2019;54:1901401.

- Manes A, Palazzini M, Leci E, Bacchi Reggiani ML, Branzi A, Galiè N. Current era survival of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease: a comparison between clinical subgroups. Eur Heart J 2014;35: 716–724.

- Savale L, Manes A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension populations of special interest: portopulmonary hypertension and pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J Suppl 2019;21:K37–K45.

- Dimopoulos K, Diller GP, Opotowsky AR, D’Alto M, Gu H, Giannakoulas G, et al. Definition and management of segmental pulmonary hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e008587.

- Amedro P, Gavotto A, Abassi H, Picot MC, Matecki S, Malekzadeh-Milani S, et al. Efficacy of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in univentricular congenital heart disease: the SV-INHIBITION study design. ESC Heart Fail 2020;7:747–756.

- Goldberg DJ, Zak V, Goldstein BH, Schumacher KR, Rhodes J, Penny DJ, et al. Results of the FUEL Trial. Circulation 2020;141:641–651.

- Ridderbos FS, Hagdorn QAJ, Berger RMF. Pulmonary vasodilator therapy as treat- ment for patients with a Fontan circulation: the Emperor’s new clothes? Pulm Circ 2018;8:2045894018811148.

- Dimopoulos K, Muthiah K, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Banner NR, Wort SJ, Swan L, et al. Heart or heart-lung transplantation for patients with congenital heart disease in England. Heart 2019;105:596–602.

- Lapa M, Dias B, Jardim C, Fernandes CJ, Dourado PM, Figueiredo M, et al. Cardiopulmonary manifestations of hepatosplenic schistosomiasis. Circulation 2009;119:1518–1523.

- Knafl D, Gerges C, King CH, Humbert M, Bustinduy AL. Schistosomiasis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev 2020;29:190089.

- Fernandes CJC, Piloto B, Castro M, Gavilanes Oleas F, Alves JL Jr, Lopes Prada LF, et al. Survival of patients with schistosomiasis-associated pulmonary arterial hyper- tension in the modern management era. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1800307.

- Weatherald J, Dorfmuller P, Perros F, Ghigna MR, Girerd B, Humbert M, et al. Pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis: a distinct entity? Eur Respir Rev 2020;29:190168.

- Humbert M, Guignabert C, Bonnet S, Dorfmuller P, Klinger JR, Nicolls MR, et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: state of the art and re- search perspectives. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801887.

- Montani D, Girerd B, Jais X, Levy M, Amar D, Savale L, et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcomes of heritable and sporadic pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: a population-based study. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:125–134.

- Perez-Olivares C, Segura de la Cal T, Flox-Camacho A, Nuche J, Tenorio J, Martinez Menaca A, et al. The role of cardiopulmonary exercise test in identifying pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2021;57:2100115.

- Bergbaum C, Samaranayake CB, Pitcher A, Weingart E, Semple T, Kokosi M, et al. A case series on the use of steroids and mycophenolate mofetil in idiopathic and her- itable pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: is there a role for immunosuppression? Eur Respir J 2021;57:2004354.

- van Loon RL, Roofthooft MT, Hillege HL, ten Harkel AD, van Osch-Gevers M, Delhaas T, et al. Pediatric pulmonary hypertension in the Netherlands: epidemiology and char- acterization during the period 1991 to 2005. Circulation 2011;124:1755–1764.

- del Cerro Marin MJ, Sabate Rotes A, Rodriguez Ogando A, Mendoza Soto A, Quero Jimenez M, Gavilan Camacho JL, et al. Assessing pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease in childhood. Data from the Spanish registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:1421–1429.

- Li L, Jick S, Breitenstein S, Hernandez G, Michel A, Vizcaya D. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in the USA: an epidemiological study in a large insured pediatric popu- lation. Pulm Circ 2017;7:126–136.

- Berger RM, Beghetti M, Humpl T, Raskob GE, Ivy DD, Jing ZC, et al. Clinical features of paediatric pulmonary hypertension: a registry study. Lancet 2012;379:537–546.

- Abman SH, Mullen MP, Sleeper LA, Austin ED, Rosenzweig EB, Kinsella JP, et al. Characterisation of paediatric pulmonary hypertensive vascular disease from the PPHNet Registry. Eur Respir J 2021;59:2003337.

- Rosenzweig EB, Abman SH, Adatia I, Beghetti M, Bonnet D, Haworth S, et al. Paediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: updates on definition, classification, diagnostics and management. Eur Respir J 2019;53:1801916.

- Haarman MG, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Vissia-Kazemier TR, Breeman KTN, Timens W, Vos YJ, et al. The genetic epidemiology of pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Pediatr 2020;225:65–73.e65.

- Levy M, Eyries M, Szezepanski I, Ladouceur M, Nadaud S, Bonnet D, et al. Genetic analyses in a cohort of children with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2016;48: 1118–1126.

- Mourani PM, Abman SH. Pulmonary hypertension and vascular abnormalities in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin Perinatol 2015;42:839–855.

- van Loon RL, Roofthooft MT, van Osch-Gevers M, Delhaas T, Strengers JL, Blom NA, et al. Clinical characterization of pediatric pulmonary hypertension: complex presentation and diagnosis. J Pediatr 2009;155:176–182.e171.

- Arjaans S, Zwart EAH, Ploegstra MJ, Bos AF, Kooi EMW, Hillege HL, et al. Identification of gaps in the current knowledge on pulmonary hypertension in ex- tremely preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 2018;32:258–267.

- Haarman MG, Do JM, Ploegstra MJ, Roofthooft MTR, Vissia-Kazemier TR, Hillege HL, et al. The clinical value of proposed risk stratification tools in pediatric pul- monary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:1312–1315.

- Beghetti M, Schulze-Neick I, Berger RM, Ivy DD, Bonnet D, Weintraub RG, et al. Haemodynamic characterisation and heart catheterisation complications in children with pulmonary hypertension: insights from the Global TOPP Registry (tracking out- comes and practice in paediatric pulmonary hypertension). Int J Cardiol 2016;203: 325–330.

- Ploegstra MJ, Zijlstra WMH, Douwes JM, Hillege HL, Berger RMF. Prognostic fac- tors in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2015;184:198–207.

- Ivy DD, Rosenzweig EB, Lemarie JC, Brand M, Rosenberg D, Barst RJ. Long-term outcomes in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension treated with bosentan in real-world clinical settings. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:1332–1338.

- Zijlstra WMH, Douwes JM, Rosenzweig EB, Schokker S, Krishnan U, Roofthooft MTR, et al. Survival differences in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: clues to a better understanding of outcome and optimal treatment strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2159–2169

- Ploegstra MJ, Douwes JM, Roofthooft MT, Zijlstra WM, Hillege HL, Berger RM. Identification of treatment goals in paediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1616–1626.

- Singh Y, Lakshminrusimha S. Pathophysiology and management of persistent pul- monary hypertension of the newborn. Clin Perinatol 2021;48:595–618.

- Arjaans S, Haarman MG, Roofthooft MTR, Fries MWF, Kooi EMW, Bos AF, et al. Fate of pulmonary hypertension associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia be- yond 36 weeks postmenstrual age. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2021;106: 45–50.

- Goss KN, Beshish AG, Barton GP, Haraldsdottir K, Levin TS, Tetri LH, et al. Early pulmonary vascular disease in young adults born preterm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:1549–1558.

- Krishnan U, Feinstein JA, Adatia I, Austin ED, Mullen MP, Hopper RK, et al. Evaluation and management of pulmonary hypertension in children with broncho- pulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 2017;188:24–34.e21.

- Vayalthrikkovil S, Vorhies E, Stritzke A, Bashir RA, Mohammad K, Kamaluddeen M, et al. Prospective study of pulmonary hypertension in preterm infants with bronch- opulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2019;54:171–178.

- Abman SH, Collaco JM, Shepherd EG, Keszler M, Cuevas-Guaman M, Welty SE, et al. Interdisciplinary care of children with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 2017;181:12–28.e11.

- Kessler R, Faller M, Weitzenblum E, Chaouat A, Aykut A, Ducolone A, et al. “Natural history” of pulmonary hypertension in a series of 131 patients with chron- ic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:219–224.

- Oswald-Mammosser M, Weitzenblum E, Quoix E, Moser G, Chaouat A, Charpentier C, et al. Prognostic factors in COPD patients receiving long-term oxy- gen therapy. Importance of pulmonary artery pressure. Chest 1995;107: 1193–1198.

- Thurnheer R, Ulrich S, Bloch KE. Precapillary pulmonary hypertension and sleep- disordered breathing: is there a link? Respiration 2017;93:65–77.

- Leon-Velarde F, Maggiorini M, Reeves JT, Aldashev A, Asmus I, Bernardi L, et al. Consensus statement on chronic and subacute high altitude diseases. High Alt Med Biol 2005;6:147–157.

- Freitas CSG, Baldi BG, Jardim C, Araujo MS, Sobral JB, Heiden GI, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: prevalence, severity and the role of carbon monoxide diffusion capacity as a screening method. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:74.

- Zeder K, Avian A, Bachmaier G, Douschan P, Foris V, Sassmann T, et al. Elevated pulmonary vascular resistance predicts mortality in COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2100944.

- Olsson KM, Hoeper MM, Pausch C, Grunig E, Huscher D, Pittrow D, et al. Pulmonary vascular resistance predicts mortality in patients with pulmonary hyper- tension associated with interstitial lung disease: results from the COMPERA regis- try. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2101483.

- Chaouat A, Bugnet AS, Kadaoui N, Schott R, Enache I, Ducolone A, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:189–194.

- Lettieri CJ, Nathan SD, Barnett SD, Ahmad S, Shorr AF. Prevalence and outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2006;129:746–752.

- Medrek SK, Sharafkhaneh A, Spiegelman AM, Kak A, Pandit LM. Admission for COPD exacerbation is associated with the clinical diagnosis of pulmonary hyper- tension: results from a Retrospective Longitudinal Study of a Veteran Population. COPD 2017;14:484–489.

- Kessler R, Faller M, Fourgaut G, Mennecier B, Weitzenblum E. Predictive factors of hospitalization for acute exacerbation in a series of 64 patients with chronic ob- structive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:158–164.

- Vizza CD, Hoeper MM, Huscher D, Pittrow D, Benjamin N, Olsson KM, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with COPD: results from COMPERA. Chest 2021;160:678–689.

- Dauriat G, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Cottin V, Lamia B, Montani D, Canuet M, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective French multicenter cohort. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021; 40:1009–1018.

- Kovacs G, Agusti A, Barbera JA, Celli B, Criner G, Humbert M, et al. Pulmonary vas- cular involvement in COPD – is there a pulmonary vascular phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:1000–1011.

- Andersen KH, Iversen M, Kjaergaard J, Mortensen J, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Bendstrup E, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and survival in pulmonary hypertension related to end- stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31: 373–380.

- Thabut G, Dauriat G, Stern JB, Logeart D, Levy A, Marrash-Chahla R, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in advanced COPD candidates for lung volume reduc- tion surgery or lung transplantation. Chest 2005;127:1531–1536.

- Carlsen J, Hasseriis Andersen K, Boesgaard S, Iversen M, Steinbruchel D, Bogelund Andersen C. Pulmonary arterial lesions in explanted lungs after transplantation cor- relate with severity of pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013;32:347–354.

- Bunel V, Guyard A, Dauriat G, Danel C, Montani D, Gauvain C, et al. Pulmonary arterial histologic lesions in patients with COPD with severe pulmonary hyperten- sion. Chest 2019;156:33–44.

- Kovacs G, Avian A, Douschan P, Foris V, Olschewski A, Olschewski H. Patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension less represented in clinical trials – who are they and how are they? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:A3979.

- Torres-Castro R, Gimeno-Santos E, Vilaro J, Roque-Figuls M, Moises J, Vasconcello-Castillo L, et al. Effect of pulmonary hypertension on exercise toler- ance in patients with COPD: a prognostic systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev 2021;30:200321.

- Nathan SD, Shlobin OA, Barnett SD, Saggar R, Belperio JA, Ross DJ, et al. Right ventricular systolic pressure by echocardiography as a predictor of pulmonary hyper- tension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2008;102:1305–1310.

- Bax S, Bredy C, Kempny A, Dimopoulos K, Devaraj A, Walsh S, et al. A stepwise composite echocardiographic score predicts severe pulmonary hypertension in pa- tients with interstitial lung disease. ERJ Open Res 2018;4:00124-2017.

- Bax S, Jacob J, Ahmed R, Bredy C, Dimopoulos K, Kempny A, et al. Right ventricular to left ventricular ratio at CT pulmonary angiogram predicts mortality in interstitial lung disease. Chest 2020;157:89–98.