TS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

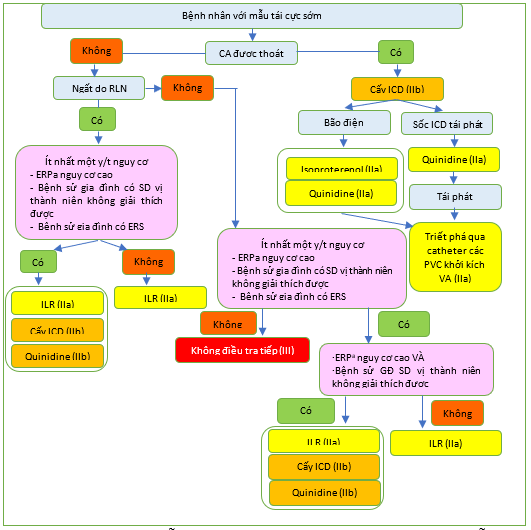

7.2.5. Hội chứng tái cực sớm

Hội chứng tái cực sớm (ERS) được chẩn đoán ở bệnh nhân được hồi sức sau PVT hoặc VF khi không có bất ký bệnh tim nào khác và mẫu tái cực sớm (ERP); Điểm J chênh lên ≥1 mm ở ≥2 chuyển đạo ECG dưới và/hoặc bên liên tiếp (Hình 32). [135.231.1017–1019] Tuy nhiên, ERP hầu hết là một biểu hiện lành tính và mức độ phổ biến của ERP đã được báo cáo là 5,8% ở người lớn và phổ biến hơn ở nam thanh niên và vận động viên. [135.231.1017–1021] Tuy nhiên, ERP được thể hiện nhiều hơn ở những người thân của các trường hợp đột tử do ngừng tim đột ngột (SADS) [282.1022] và những người sống sót sau CA. [182.916] Hiệu quả chẩn đoán và tiện ích của xét nghiệm di truyền thấp. [1023–1025] Các đặc điểm ECG có nguy cơ cao đã được đề xuất để tăng khả năng xảy ra ERS: sóng J chiếm ưu thế ≥2 mm, thay đổi động học trong chênh lên của điểm J (> 0,1 mV) và các sóng J kết hợp với đoạn ST đi ngang (horizontal) hoặc ST đi xuống (descenting) (Hình 34). [231.1026.1027] ERP có đoạn ST nằm ngang có liên quan đến nguy cơ rối loạn nhịp tim ở người già và quần thể IVF. [1027] Tuy nhiên, những người sống sót sau ERS và người thân của các trường hợp SADS cũng biểu hiện tỷ lệ đoạn ST đi lên (ascending) /chênh xuống đi lên (upsloping) cao hơn so với nhóm chứng. [282,1018] Ít nhất 40% bệnh nhân ERS bị VF có các đợt liên tiếp, với 27% bị nhiều đợt. [231,1028,1029] Truyền isoproterenol có hiệu quả trong việc ức chế cấp thời ICD phát sốc và bão điện. [1030–1032] AAD chẹn kênh kali ra ngoài có thể ngăn ngừa VF cấp thời. [922,1030,1033] Một nghiên cứu hồi cứu đa trung tâm cho thấy giảm VF tái phát sau khi bắt đầu dùng quinidin. [1030] Các chất ức chế Phosphodiesterase -3 như cilostazol và milrinone cũng làm giảm VF tái phát. [1032] Triệt phá PVC khởi kích, thường là từ hệ thống Purkinje, có tỷ lệ thành công cấp thời từ 87–100% và có thể có hiệu quả trong việc ngăn ngừa tái phát ở bệnh nhân VF kháng thuốc. [1010,1017] Lập bản đồ điện giải phẫu chi tiết có thể bộc lộ những thay đổi cấu trúc cục bộ ở 39% bệnh nhân ERS. [1010] Việc triệt phá những khu vực này đã ngăn chặn thành công cơn bão điện và có thể là một lựa chọn điều trị ở các trung tâm có kinh nghiệm. Liệu việc triệt phá qua catheter có cải thiện kết quả lâu dài hay không hiện vẫn chưa rõ.

Không có dữ liệu về phân tầng nguy cơ ở bệnh nhân nghi ngờ ERS mà không có CA trước đó. Ở những cá nhân có ERP và ngất không giải thích được, người ta đã khuyến cáo nên xem xét theo dõi bằng ILR. Vì tiên lượng của các đối tượng không có triệu chứng với ERP là tốt nên điều trị bằng ICD thường không được chỉ định. [1034–1036] Tuy nhiên, nếu có ERP có nguy cơ cao và tiền sử gia đình mắc bệnh SD ở trẻ vị thành niên không rõ nguyên nhân, thì việc cấy ICD hoặc quinidine có thể được xem xét.

Bảng khuyến cáo 44 – Khuyến cáo dành cho quản lý bệnh nhân có hội chứng tái cực sớm

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Chẩn đoán | ||

| Khuyến nghị ERP được chẩn đoán khi điểm J chênh lên ≥1 mm ở hai chuyển đạo ECG dưới và/hoặc bên liên tiếp. [1017,1018] | I | C |

| Khuyến cáo chẩn đoán ERS ở bệnh nhân được hồi sức sau VF/PVT không giải thích được khi có ERP. [1017,1018] | I | C |

| Ở một nạn nhân SCD có khám nghiệm tử thi và đánh giá biểu đồ y tế âm tính, và ECG trước khi chết chứng minh ERP, chẩn đoán ERS nên được xem xét. [1017,1018] |

IIa |

C |

| Người thân thế hệ thứ nhất của bệnh nhân ERS nên được xem xét để đánh giá lâm sàng về ERP với các tính năng bổ xung nguy cơ.c, [1022,1037] |

IIa |

B |

| Có thể xem xét tiếp tục xét nghiệm di truyền ở bệnh nhân ERS. [1023,1025] | IIb | C |

| Đánh giá lâm sàng không được khuyến khích thường xuyên ở những đối tượng không có triệu chứng với ERP. [1038,1039] | III | C |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ, ngăn ngừa SCD và điều trị VA | ||

| Cấy ICD được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán ERS đã sống sót sau CA. [1017] | I | B |

| Truyền isoproterenol nên được xem xét cho bệnh nhân ERS bị bão điện. [1017,1030–1032] | IIa | B |

| Quinidine bổ xung vào ICD nên được xem xét cho VF tái phát ở bệnh nhân ERS. [922,1030,1033] | IIa | B |

| ILR nên được xem xét ở những cá nhân có ERP và có ít nhất một nguy cơ đặc trưng hoặc ngất do rối loạn nhịp tim. [1020] | IIa | C |

| Triệt phá PVC nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân ERS có các cơn VF tái phát được kích hoạt bởi PVC tương tự không đáp ứng với điều trị nội khoa. [1010] | IIa | C |

| Cấy ICD hoặc quinidine có thể được xem xét ở những cá nhân có ERP và ngất do rối loạn nhịp tim và các đặc điểm nguy cơ bổ sung.d, [1030,1033] | IIb | C |

| Cấy ICD hoặc quinidine có thể được xem xét ở những cá nhân không có triệu chứng nhưng có ERPc nguy cơ cao với tiền sử gia đình mắc SD vị thành niên không giải thích được. [1030,1033] | IIb | C |

| Cấy ICD không được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân không có triệu chứng với ERP đơn độc. [1034,1035,1040] | III | C |

CA: ngừng tim; ECG: điện tâm đồ; ERP: mẫu tái cực sớm; ERS: hội chứng tái cực sớm; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; ILR: máy ghi vòng lặp có thể cấy; PVC: phức hợp thất sớm; PVT: nhịp nhanh thất; SCD: đột tử do tim; SD: đột tử; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VF: rung tâm thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

c Đặc điểm nguy cơ cao của ERP: sóng J > 2 mm, thay đổi động ở điểm J và hình thái ST. [1020,1041]

d ERP nguy cơ cao: tiền sử gia đình SD < 40 tuổi không rõ nguyên nhân, tiền sử gia đình mắc ERS.

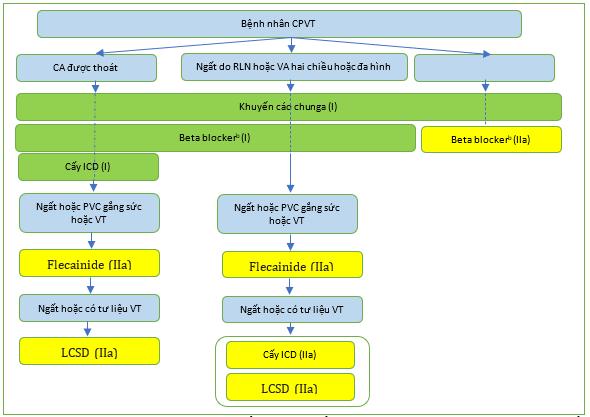

7.2.6. Nhịp nhanh thất đa hình do tiết catecholamine

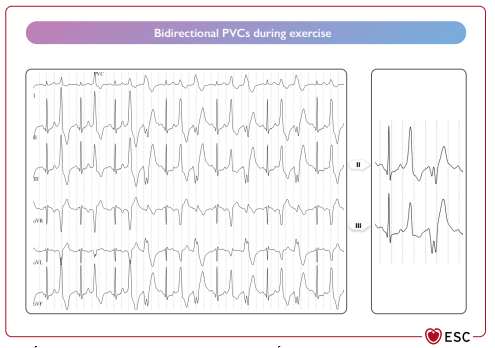

CPVT (catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia) là một rối loạn di truyền được đặc trưng bởi VT và PVT hai chiều do catecholamine gây ra khi không có SHD hoặc thiếu máu cục bộ. Căn bệnh này có tỷ lệ hiện mắc ước tính là 1 trên 10.000 (Hình 35). [135]

Có hai loại di truyền chính: rối loạn gen trội do đột biến gen mã hóa thụ thể ryanodine của tim (RYR2) và rối loạn lặn do đột biến ở tim

gen calsequestrin (CASQ2). [135,178] Đột biến ở TRDN và

CALM1-3 đã được xác định ở những bệnh nhân có dạng VA do catecholamine không điển hình. [1042] Tuy nhiên, tại thời điểm hiện tại, vẫn chưa rõ liệu chúng có phải là các thực thể rối loạn nhịp tim riêng biệt hay không. [1043] Bệnh nhân có đột biến KCNJ2 gây ra hội chứng Andersen–Tawil type 1 đôi khi có thể biểu hiện PVT hai chiều và PVT, nhưng được phân biệt bằng các mối liên hệ hội chứng của chúng. [1044]

Hình 34 Quản lý bệnh nhân có mẫu tái cực sớm / hội chứng tái cực sớm. ERP: mẫu tái cực sớm; ERS: hội chứng tái cực sớm; ICD: máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; ILR: máy ghi vòng có thể cấy; PVC: phức hợp thất sớm; SD: đột tử. a ERP có đặc điểm nguy cơ cao: Sóng J > 2 mm, hình thái ST thay đổi động học.

Các biểu hiện lâm sàng của CPVT thường xảy ra trong thập niên đầu đời do hoạt động thể chất hoặc căng thẳng về cảm xúc. [1045] Hầu hết bệnh nhân CPVT đều có ECG và siêu âm tim bình thường. Tuy nhiên, một số bệnh nhân có biểu hiện bất thường ECG nhẹ, chẳng hạn như nhịp tim chậm xoang và sóng U nổi bật. Test gắng sức là xét nghiệm chẩn đoán quan trọng nhất, vì nó gợi ra PVT hai chiều hoặc PVT để phân biệt giúp xác định chẩn đoán (Hình 36). [135] Chẩn đoán cũng có thể được thực hiện khi có đột biến gen liên quan đến CPVT. Thử thách bằng epinephrine hoặc isoproterenol có thể được xem xét khi test gắng sức không khả thi.[1046]

Chẩn đoán ở trẻ em, thiếu liệu pháp chẹn beta và rối loạn nhịp phức tạp trong quá trình test gắng sức khi dùng đủ liều thuốc chẹn beta là những yếu tố dự báo độc lập cho các biến cố loạn nhịp tim [1047] Hạn chế gắng sức và dùng thuốc chẹn beta không có hoạt tính giao cảm nội tại là ưu tiên hàng đầu điều trị cho bệnh nhân CPVT [135] Thuốc chẹn beta không chọn lọc như nadolol và propranolol được ưa thích hơn. [1048,1049] Hội thảo này đã xác nhận chỉ định điều trị cho các thành viên gia đình có di truyền dương tính bằng thuốc chẹn beta, ngay cả khi không tập thể dục- hoặc VA do căng thẳng gây ra [1047,1050] Dữ liệu cho thấy rằng flecainide làm giảm đáng kể gánh nặng VA ở bệnh nhân CPVT và nên được xem xét bổ sung cùng với thuốc chẹn beta khi việc kiểm soát rối loạn nhịp tim không đầy đủ. [1051–1053] Ở những bệnh nhân được lựa chọn không dung nạp với điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn beta, điều trị chỉ bằng thuốc flecainide là một lựa chọn.[1054]

Hình 35 Quản lý bệnh nhân nhịp nhanh thất đa hình tiết catecholamine. CPVT: nhịp nhanh thất đa hình do catecholamine; ICD, máy khử rung tim có thể cấy; LCSD: hủy bỏ thần kinh giao cảm tim trái; PVC, phức hợp thất sớm; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VT, nhịp nhanh thất. a Khuyến cáo chung: tránh các môn thể thao cạnh tranh, tránh tập luyện nặng, tránh môi trường căng thẳng. b Thuốc chẹn beta được ưu tiên: nadolol, propranolol.

Bảo vệ tối đa bằng thuốc chẹn beta, flecainide và ICD được chỉ định ở những người sống sót sau CA. ICD cũng nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân CPVT có VA bùng phát trên nền thuốc chẹn beta và flecainide [135] Tuy nhiên, ICD nên được lập trình với độ trễ dài và tần số cao trước khi khử rung tim, vì việc bắt đầu VT hai chiều đáp ứng với khử rung tim kém hiệu quả hơn so với PVT tiếp theo /VF, và những cú sốc đau đớn có thể gây ra tình trạng rối loạn nhịp tim nặng hơn và liên hồi (incessant).[1055]

LCSD đã được đề xuất như một liệu pháp bổ sung ở những bệnh nhân mà việc điều trị bằng thuốc không hiệu quả hoặc khả thi. Mặc dù LCSD làm giảm sự tái phát của các biến cố tim mạch nặng ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng trước đó, nhưng một phần ba số bệnh nhân vẫn bị tái phát rối loạn nhịp tim.[1056] Do đó, LCSD chưa được coi là sự thay thế cho liệu pháp ICD mà là liệu pháp bổ sung ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng.

Một tổng quan hệ thống gần đây của 53 nghiên cứu bao gồm bệnh nhân CPVT có ICD đã kết luận bệnh nhân phòng ngừa thứ phát được quản lý bằng OMT, LCSD và hạn chế gắng sức có thể làm giảm việc sử dụng ICD. [1057] Quan sát này được hỗ trợ bằng một cuộc điều tra đa trung tâm tiếp theo cho thấy tất cả có 3 SCD được quan sát đều xảy ra ở những bệnh nhân có ICD. [1058] Hiện tại, dựa trên bằng chứng này, có vẻ còn sớm để hạ cấp cấy ICD ở những người sống sót sau CA với CPVT. [1057]

Hình 36 Test gắng sức ở bệnh nhân có nhịp nhanh thất đa hình do catecholamine. PVC: phúc hợp thất sớm. Bidirectional PVCs during exercise: phưc hợp thất sớm hai chiều trong quá trình gắng sức.

Hình 36 Test gắng sức ở bệnh nhân có nhịp nhanh thất đa hình do catecholamine. PVC: phúc hợp thất sớm. Bidirectional PVCs during exercise: phưc hợp thất sớm hai chiều trong quá trình gắng sức.

Bảng khuyến cáo 45 – Khuyến cáo cho quản lý bệnh nhân nhịp nhanh thất đa hình do catecholamine

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Chẩn đoán | ||

| Khuyến cáo CPVT được chẩn đoán khi có tim cấu trúc bình thường, ECG bình thường và PVT hai chiều do gắng sức hoặc cảm xúc gây ra. | I | C |

| Khuyến cáo chẩn đoán CPVT ở những bệnh nhân mang đột biến gen gây bệnh. | I | C |

| Xét nghiệm di truyền và tư vấn di truyền được chỉ định ở những bệnh nhân nghi ngờ lâm sàng hoặc chẩn đoán lâm sàng CPVT. | I | C |

| Thử thách dùng epinephrine hoặc isoproterenol có thể được xem xét để chẩn đoán CPVT khi không thể thực hiện được test gắng sức. | IIb | C |

| Khuyến cáo chung | ||

| Tránh các môn thể thao cạnh tranh, gắng sức nặng và tiếp xúc với môi trường căng thẳng được khuyến cáo ở tất cả bệnh nhân CPVT. | I | C |

| Can thiệp điều trị | ||

| Thuốc chẹn beta, lý tưởng là không chọn lọc (nadolol hoặc propranolol) được khuyến cáo ở tất cả các bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán lâm sàng CPVT.[1045,1048,1059] | I | C |

| Cấy ICD kết hợp với thuốc chẹn beta và flecainide được khuyến cáo ở bệnh nhân CPVT sau khi CA được thoát.[1045,1047,1060] | I | C |

| Điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn beta nên được xem xét đối với bệnh nhân CPVT dương tính về mặt di truyền không có kiểu hình.[1047,1050] | IIa | C |

| LCSD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán CPVT khi sự kết hợp giữa thuốc chẹn beta và flecainide ở liều điều trị không hiệu quả, không dung nạp hoặc chống chỉ định.[1056] | IIa | C |

| Việc cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân CPVT bị ngất do rối loạn nhịp tim và/hoặc được ghi nhận VT hai chiều/PVT trong khi đang dùng liều thuốc chẹn beta dung nạp cao nhất và đang dùng flecainide. [1047,1050] | IIa | C |

| Flecainide nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân CPVT bị ngất tái phát, VT đa hình/hai chiều hoặc PVC gắng sức dai dẳng, trong khi đang dùng thuốc chẹn beta ở mức liều dung nạp cao nhất. [1052,1053,1060] | IIa | C |

| PES không được khuyến cáo để phân tầng nguy cơ SCD.

III C |

III | C |

CA: ngừng tim; CPVT: nhịp nhanh thất do catecholaminergic; ECG: điện tâm đồ: ICD: máy khử rung tim cấy ghép: LCSD: hủy bỏ thần kinh giao cảm tim trái; PVT: nhịp nhanh thất đa hình; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

a Class khuyến nghị.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

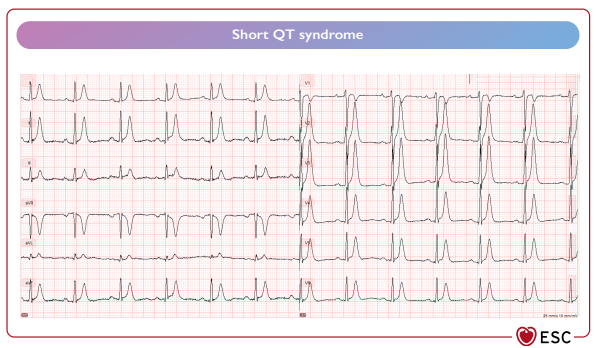

7.2.7 Hội chứng QT ngắn

Hội chứng QT ngắn (SQTS) là một rối loạn di truyền hiếm gặp được đặc trưng bởi khoảng QT ngắn, AF và VF sớm trong bối cảnh tim có cấu trúc bình thường. [1061] Nó có liên quan đến việc tăng đột biến chức năng ở KCNH2, KCNQ1 và mất chức năng ở SLC4A. [1062,1063] Hội đồng này đề xuất hai ngưỡng giới hạn QTc để chẩn đoán: A QTc ≤ 320 ms hoặc B a QTc ≤360 ms kết hợp với tiền sử gia đình mắc SQTS, CA được thoát khi không có bệnh tim hoặc đột biến gây bệnh [1064–1067] (Hình 37). Bệnh có tỷ lệ tử vong cao ở mọi lứa tuổi, kể cả những tháng đầu đời. [1063,1068,1069] Xác suất CA đầu tiên ở độ tuổi 40 là > 40%.[1068] Trong khi ICD được sử dụng để phòng ngừa thứ phát, [1069] phòng ngừa nguyên phát vẫn còn gây tranh cãi và dựa trên các triệu chứng trước đó và khoảng QTc . [1063,1068,1069] Quinidine hiện là thuốc AAD được hỗ trợ tốt nhất, nhưng cần được theo dõi tình trạng kéo dài QT quá mức, trong khi isoprenaline có thể được xem xét trong cơn bão điện.[1070,1071] Các thuốc làm khoảng QT ngắn lại nên được tránh, ví dụ. nicorandil. [1072] Việc cấy máy ghi vòng lặp nên được xem xét ở trẻ em và bệnh nhân trẻ tuổi SQTS không có triệu chứng.

Bảng khuyến cáo 46 – Khuyến cáo cho quản lý bệnh nhân mắc hội chứng QT ngắn

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Chẩn đoán | ||

| Khuyến cáo SQTS được chẩn đoán khi có QTc ≤360 ms và một hoặc nhiều dấu hiệu sau: (a) đột biến gây bệnh, (b) tiền sử gia đình mắc SQTS, (c) sống sót sau một đợt VT/VF trong trường hợp không có bệnh tim. [1061,1068] |

I |

C |

| Xét nghiệm di truyền được chỉ định ở những bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán mắc SQTS.[1063] |

I |

C |

| SQTS nên được xem xét khi có QTc ≤320 ms [1064–1067,1073,1074] | IIa | C |

| SQTS nên được xem xét khi có QTc ≥320 ms và ≤ 360 ms và ngất do rối loạn nhịp tim. | IIa | C |

| SQTS có thể được xem xét khi có QTc ≥320 ms và ≤ 360 ms và tiền sử gia đình mắc SD ở độ tuổi < 40 tuổi. | IIb | C |

| Phân tầng nguy cơ, dự phòng SCD và điều trị VA | ||

| Cấy ICD được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán SQTS: (a) là những người sống sót sau CA được thoát và/hoặc (b) đã ghi nhận VT tự phát dai dẳng được chứng minh bằng tư liệu. [1063] |

I |

C |

| ILR nên được xem xét ở những bệnh nhân SQTS trẻ tuổi. Cấy ICD nên được xem xét ở bệnh nhân SQTS bị ngất do loạn nhịp. | IIa | C |

| Quinidine có thể được xem xét ở (a) bệnh nhân SQTS đủ điều kiện đặt ICD nhưng có chống chỉ định với ICD hoặc từ chối nó, và (b) bệnh nhân SQTS không có triệu chứng và tiền sử gia đình mắc SCD.[1069–1071] |

IIb |

C |

| Isoproterenol có thể được xem xét ở bệnh nhân SQTS bị bão điện.[1075] | IIb | C |

| PES không được khuyến cáo để phân tầng nguy cơ SCD ở bệnh nhân SQTS. | III | C |

CA: ngừng tim; ICD: máy khử rung tim cấy ghép; ILR: máy ghi vòng lặp có thể cấy, SCD: đột tử do tim; SD: đột tử; SQTS: hội chứng QT ngắn; VA: rối loạn nhịp thất; VF: rung thất; VT: nhịp nhanh thất.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

Hình 37 Hội chứng QT ngăn. (Short QT syndrome)

Hình 37 Hội chứng QT ngăn. (Short QT syndrome)

(Còn nữa)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO (911 – 1075)

- Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with apparently normal heart. Need for definition and standardized clinical evaluation. Consensus statement of the joint steering committees of the unexplained cardiac arrest registry of Europe and of

the idiopathic ventricular fibrillation registry of the United States. Circulation 1997;95:265–272. - Leenhardt A, Glaser E, Burguera M, Nürnberg M, Maison-Blanche P, Coumel P. Short-coupled variant of torsade de pointes. A new electrocardiographic entity in the spectrum of idiopathic ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation 1994;89: 206–215.

913. Eisenberg SJ, Scheinman MM, Dullet NK, Finkbeiner WE, Griffin JC, Eldar M, et al. Sudden cardiac death and polymorphous ventricular tachycardia in patients with normal QT intervals and normal systolic cardiac function. Am J Cardiol 1995;75: 687–692. - Asatryan B, Schaller A, Seiler J, Servatius H, Noti F, Baldinger SH, et al. Usefulness of genetic testing in sudden cardiac arrest survivors with or without previous clinical evidence of heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2019;123:2031–2038.

- Visser M, Dooijes D, van der Smagt JJ, van der Heijden JF, Doevendans PA, Loh P, et al. Next-generation sequencing of a large gene panel in patients initially diagnosed with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2017;14:1035–1040.

- Honarbakhsh S, Srinivasan N, Kirkby C, Firman E, Tobin L, Finlay M, et al. Medium-term outcomes of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation survivors and family screening: a multicentre experience. Europace 2017;19:1874–1880.

- Meissner MD, Lehmann MH, Steinman RT, Mosteller RD, Akhtar M, Calkins H, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in patients without significant structural heart disease: a multicenter experience with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;21:1406–1412.

- Conte G, Caputo ML, Regoli F, Marcon S, Klersy C, Adjibodou B, et al. True idiopathic ventricular fibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors in the Swiss Canton Ticino: prevalence, clinical features, and long-term follow-up. Europace 2017;19:259 266.

919. Stampe NK, Jespersen CB, Glinge C, Bundgaard H, Tfelt-Hansen J, Winkel BG. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of arrhythmia during follow-up of patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31: 2677–2686. - Conte G, Belhassen B, Lambiase P, Ciconte G, de Asmundis C, Arbelo E, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to idiopathic ventricular fibrillation in patients with normal electrocardiograms: results from a multicentre long-term registry. Europace 2019;21:1670–1677.

- Blom LJ, Visser M, Christiaans I, Scholten MF, Bootsma M, van den Berg MP, et al. Incidence and predictors of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy and its complications in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation patients. Europace 2019;21: 1519–1526.

922. Malhi N, Cheung CC, Deif B, Roberts JD, Gula LJ, Green MS, et al. Challenge and impact of quinidine access in sudden death syndromes: a national experience. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:376–382. - Belhassen B, Glick A, Viskin S. Excellent long-term reproducibility of the electrophysiologic efficacy of quinidine in patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2009;32:294–301.

- Belhassen B, Shapira I, Shoshani D, Paredes A, Miller H, Laniado S. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation: inducibility and beneficial effects of class I antiarrhythmic agents. Circulation 1987;75:809–816.

- Viskin S, Belhassen B. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Am Heart J 1990;120: 661–671. 926. Belhassen B, Viskin S, Fish R, Glick A, Setbon I, Eldar M. Effects of electrophysiologic-guided therapy with Class IA antiarrhythmic drugs on the longterm outcome of patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation with or without the Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999;10:1301–1312.

- Sadek MM, Benhayon D, Sureddi R, Chik W, Santangeli P, Supple GE, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the moderator band: electrocardiographic characteristics and treatment by catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:67–75.

- Van Herendael H, Zado ES, Haqqani H, Tschabrunn CM, Callans DJ, Frankel DS,

et al. Catheter ablation of ventricular fibrillation: importance of left ventricular outflow tract and papillary muscle triggers. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:566–573. - Santoro F, Di Biase L, Hranitzky P, Sanchez JE, Santangeli P, Perini AP, et al. Ventricular fibrillation triggered by PVCs from papillary muscles: clinical features and ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25:1158–1164.

- Nakamura T, Schaeffer B, Tanigawa S, Muthalaly RG, John RM, Michaud GF, et al.

Catheter ablation of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation in patients with and without structural heart disease. Heart Rhythm 2019;16:1021–1027. - Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, Crampton RS, Tzivoni D, Locati EH, MacCluer J, et al. The long QT syndrome. Prospective longitudinal study of 328 families. Circulation 1991;84:1136–1144.

932. Schwartz PJ, Ackerman MJ, Antzelevitch C, Bezzina CR, Borggrefe M, Cuneo BF, et al. Inherited cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:58. - Andersen ED, Krasilnikoff PA, Overvad H. Intermittent muscular weakness, extrasystoles, and multiple developmental anomalies. A new syndrome? Acta Paediatr Scand 1971;60:559–564.

- Tawil R, Ptacek LJ, Pavlakis SG, DeVivo DC, Penn AS, Ozdemir C, et al. Andersen’s syndrome: potassium-sensitive periodic paralysis, ventricular ectopy, and dysmorphic features. Ann Neurol 1994;35:326–330.

- Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, et al. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:8089–8096; discussion 8086–8088.

- Jervell A, Lange-Nielsen F. Congenital deaf-mutism, functional heart disease with prolongation of the Q-T interval and sudden death. Am Heart J 1957;54:59–68.

- Schwartz PJ, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Crampton RS. Diagnostic criteria for the long QT syndrome. An update. Circulation 1993;88:782–784.

- Rautaharju PM, Zhang Z-M, Prineas R, Heiss G. Assessment of prolonged QT and JT intervals in ventricular conduction defects. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:1017–1021.

- Viskin S, Postema PG, Bhuiyan ZA, Rosso R, Kalman JM, Vohra JK, et al. The response of the QT interval to the brief tachycardia provoked by standing: a bedside test for diagnosing long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1955–1961.

- Mazzanti A, Maragna R, Vacanti G, Monteforte N, Bloise R, Marino M, et al. Interplay between genetic substrate, QTc duration, and arrhythmia risk in patients with long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1663–1671.

- Behr ER, Roden D. Drug-induced arrhythmia: pharmacogenomic prescribing? Eur Heart J 2013;34:89–95.

- Weeke PE, Kellemann JS, Jespersen CB, Theilade J, Kanters JK, Hansen MS, et al. Long-term proarrhythmic pharmacotherapy among patients with congenital long QT syndrome and risk of arrhythmia and mortality. Eur Heart J 2019;40: 3110–3117.

943. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Napolitano C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation 2001;103:89–95. - Chockalingam P, Crotti L, Girardengo G, Johnson JN, Harris KM, van der Heijden JF, et al. Not all beta-blockers are equal in the management of long QT syndrome types 1 and 2: higher recurrence of events under metoprolol. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2092–2099.

945. Ahn J, Kim HJ, Choi J-I, Lee KN, Shim J, Ahn HS, et al. Effectiveness of beta-blockers depending on the genotype of congenital long-QT syndrome: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185680. - Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Grillo M, Bloise R, Ronchetti E, et al. Association of long QT syndrome loci and cardiac events among patients treated with beta-blockers. JAMA 2004;292:1341–1344.

- Mazzanti A, Trancuccio A, Kukavica D, Pagan E, Wang M, Mohsin M, et al. Independent validation and clinical implications of the risk prediction model for long QT syndrome (1-2-3-LQTS-Risk). Europace 2021;24:697–698.

- Mazzanti A, Maragna R, Faragli A, Monteforte N, Bloise R, Memmi M, et al. Gene-specific therapy with mexiletine reduces arrhythmic events in patients with long QT syndrome type 3. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1053–1058.

- Ruan Y, Liu N, Bloise R, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Gating properties of SCN5A mutations and the response to mexiletine in long-QT syndrome type 3 patients. Circulation 2007;116:1137–1144.

- Zhu W, Mazzanti A, Voelker TL, Hou P, Moreno JD, Angsutararux P, et al. Predicting patient response to the antiarrhythmic mexiletine based on genetic variation. Circ Res 2019;124:539–552.

951. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Bloise R, Crotti L, Ronchetti E. The elusive link between LQT3 and Brugada syndrome: the role of flecainide challenge. Circulation 2000;102:945–947. - Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Schwartz PJ, Crampton RS, Benhorin J, et al. Effectiveness and limitations of beta-blocker therapy in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2000;101:616–623.

953. Jons C, Moss AJ, Goldenberg I, Liu J, McNitt S, Zareba W, et al. Risk of fatal arrhythmic events in long QT syndrome patients after syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55: 783–788.

954. Liu JF, Jons C, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Peterson DR, Qi M, et al. Risk factors for recurrent syncope and subsequent fatal or near-fatal events in children and adolescents with long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:941–950. - Seth R, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Zareba W, Andrews ML, Qi M, et al. Long QT syndrome and pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1092–1098.

- Goldenberg I, Horr S, Moss AJ, Lopes CM, Barsheshet A, McNitt S, et al. Risk for life-threatening cardiac events in patients with genotype-confirmed long-QT syndrome and normal-range corrected QT intervals. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:51–59.

- Jang SY, Cho Y, Kim NK, Kim C-Y, Sohn J, Roh J-H, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic left cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with hereditary ventricular arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2017;40:232–241.

- Waddell-Smith KE, Ertresvaag KN, Li J, Chaudhuri K, Crawford JR, Hamill JK, et al. Physical and psychological consequences of left cardiac sympathetic denervation in long-QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:1151–1158.

- Anderson HN, Bos JM, Rohatgi RK, Ackerman MJ. The effect of left cardiac sympathetic denervation on exercise in patients with long QT syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:1084–1090.

- Bos JM, Bos KM, Johnson JN, Moir C, Ackerman MJ. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation in long QT syndrome: analysis of therapeutic nonresponders. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6:705–711.

- Bhandari AK, Shapiro WA, Morady F, Shen EN, Mason J, Scheinman MM. Electrophysiologic testing in patients with the long QT syndrome. Circulation 1985;71:63–71.

962. Zareba W, Moss AJ, Daubert JP, Hall WJ, Robinson JL, Andrews M. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator in high-risk long QT syndrome patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2003;14:337–341. - Schwartz PJ, Spazzolini C, Priori SG, Crotti L, Vicentini A, Landolina M, et al. Who are the long-QT syndrome patients who receive an implantable cardioverterdefibrillator and what happens to them?: Data from the European long-QT syndrome implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (LQTS ICD) registry. Circulation 2010;122:1272–1282.

- Delannoy E, Sacher F, Maury P, Mabo P, Mansourati J, Magnin I, et al. Cardiac characteristics and long-term outcome in Andersen-Tawil syndrome patients related to KCNJ2 mutation. Europace 2013;15:1805–1811.

- Inoue YY, Aiba T, Kawata H, Sakaguchi T, Mitsuma W, Morita H, et al. Different responses to exercise between Andersen-Tawil syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Europace 2018;20:1675–1682.

- Krych M, Biernacka EK, Ponińska J, Kukla P, Filipecki A, Gajda R, et al. Andersen-Tawil syndrome: clinical presentation and predictors of symptomatic arrhythmias—possible role of polymorphisms K897T in KCNH2 and H558R in SCN5A gene. J Cardiol 2017;70:504–510.

- Mazzanti A, Guz D, Trancuccio A, Pagan E, Kukavica D, Chargeishvili T, et al. Natural history and risk stratification in Andersen-Tawil syndrome type 1. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:1772–1784.

- Zhang L, Benson DW, Tristani-Firouzi M, Ptacek LJ, Tawil R, Schwartz PJ, et al. Electrocardiographic features in Andersen-Tawil syndrome patients with KCNJ2 mutations: characteristic T-U-wave patterns predict the KCNJ2 genotype. Circulation 2005;111:2720–2726.

- Horigome H, Ishikawa Y, Kokubun N, Yoshinaga M, Sumitomo N, Lin L, et al. Multivariate analysis of TU wave complex on electrocardiogram in Andersen-Tawil syndrome with KCNJ2 mutations. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2020;25:e12721.

- Miyamoto K, Aiba T, Kimura H, Hayashi H, Ohno S, Yasuoka C, et al. Efficacy and safety of flecainide for ventricular arrhythmias in patients with Andersen-Tawil syndrome with KCNJ2 mutations. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:596–603.

- Radwański PB, Greer-Short A, Poelzing S. Inhibition of Na+ channels ameliorates arrhythmias in a drug-induced model of Andersen-Tawil syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:255–263.

- Tristani-Firouzi M, Jensen JL, Donaldson MR, Sansone V, Meola G, Hahn A, et al. Functional and clinical characterization of KCNJ2 mutations associated with LQT7 (Andersen syndrome). J Clin Invest 2002;110:381–388.

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 2005;111:659–670

- Savastano S, Rordorf R, Vicentini A, Petracci B, Taravelli E, Castelletti S, et al. A comprehensive electrocardiographic, molecular, and echocardiographic study of Brugada syndrome: validation of the 2013 diagnostic criteria. Heart Rhythm 2014;

11:1176–1183.

975. Richter S, Sarkozy A, Paparella G, Henkens S, Boussy T, Chierchia G-B, et al. Number of electrocardiogram leads displaying the diagnostic coved-type pattern in Brugada syndrome: a diagnostic consensus criterion to be revised. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1357–1364.

976. Veltmann C, Papavassiliu T, Konrad T, Doesch C, Kuschyk J, Streitner F, et al. Insights into the location of type I ECG in patients with Brugada syndrome: correlation of ECG and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9:414–421.

977. Adler A, Rosso R, Chorin E, Havakuk O, Antzelevitch C, Viskin S. Risk stratification in Brugada syndrome: clinical characteristics, electrocardiographic parameters, and auxiliary testing. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:299–310. - Hasdemir C, Payzin S, Kocabas U, Sahin H, Yildirim N, Alp A, et al. High prevalence of concealed Brugada syndrome in patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:1584–1594.

- Behr ER, Ben-Haim Y, Ackerman MJ, Krahn AD, Wilde AAM. Brugada syndrome and reduced right ventricular outflow tract conduction reserve: a final common pathway? Eur Heart J 2021;42:1073–1081.

- Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, Meregalli PG, Gaita F, Tan HL, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: results from the FINGER Brugada syndrome registry. Circulation 2010;121:635–643.

- Amin AS, Meregalli PG, Bardai A, Wilde AAM, Tan HL. Fever increases the risk for cardiac arrest in the Brugada syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:216–218.

982. Adler A, Topaz G, Heller K, Zeltser D, Ohayon T, Rozovski U, et al. Fever-induced Brugada pattern: how common is it and what does it mean? Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1375–1382.

983. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, Pappone C, Della Bella P, Giordano U, et al. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation 2002;105:1342–1347. - Rizzo A, Borio G, Sieira J, Van Dooren S, Overeinder I, Bala G, et al. Ajmaline testing and the Brugada syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2020;135:91–98.

- Poli S, Toniolo M, Maiani M, Zanuttini D, Rebellato L, Vendramin I, et al. Management of untreatable ventricular arrhythmias during pharmacologic challenges with sodium channel blockers for suspected Brugada syndrome. Europace 2018;20:234–242.

986. Hasdemir C, Juang JJ-M, Kose S, Kocabas U, Orman MN, Payzin S, et al. Coexistence

of atrioventricular accessory pathways and drug-induced type 1 Brugada pattern. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018;41:1078–1092. - Probst V, Wilde AAM, Barc J, Sacher F, Babuty D, Mabo P, et al. SCN5A mutations and the role of genetic background in the pathophysiology of Brugada syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2009;2:552–557.

- Meregalli PG, Tan HL, Probst V, Koopmann TT, Tanck MW, Bhuiyan ZA, et al. Type of SCN5A mutation determines clinical severity and degree of conduction slowing in loss-of-function sodium channelopathies. Heart Rhythm 2009;6:341–348.

- Ishikawa T, Kimoto H, Mishima H, Yamagata K, Ogata S, Aizawa Y, et al. Functionally validated SCN5A variants allow interpretation of pathogenicity and prediction of lethal events in Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J 2021;42:2854–2863.

- Gehi AK, Duong TD, Metz LD, Gomes JA, Mehta D. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2006;17:577–583.

991. McNamara DA, Goldberger JJ, Berendsen MA, Huffman MD. Implantable defibrillators versus medical therapy for cardiac channelopathies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD011168. - Priori SG, Gasparini M, Napolitano C, Della Bella P, Ottonelli AG, Sassone B, et al. Risk stratification in Brugada syndrome: results of the PRELUDE (Programmed ELectrical stimUlation preDictive valuE) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:37–45.

- Dereci A, Yap S-C, Schinkel AFL. Meta-analysis of clinical outcome after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation in patients with Brugada syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:141–148.

- Conte G, Sieira J, Ciconte G, de Asmundis C, Chierchia G-B, Baltogiannis G, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in Brugada syndrome: a 20-year single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:879–888.

- Mascia G, Della Bona R, Ameri P, Canepa M, Porto I, Brignole M. Brugada syndrome and syncope: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:3334–3338.

- Subramanian M, Prabhu MA, Harikrishnan MS, Shekhar SS, Pai PG, Natarajan K. The utility of exercise testing in risk stratification of asymptomatic patients with type 1 Brugada pattern. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2017;28:677–683.

- Kubala M, Aïssou L, Traullé S, Gugenheim A-L, Hermida J-S. Use of implantable loop recorders in patients with Brugada syndrome and suspected risk of ventricular arrhythmia. Europace 2012;14:898–902.

- Sakhi R, Assaf A, Theuns DAMJ, Verhagen JMA, Szili-Torok T, Roos-Hesselink JW, et al. Outcome of insertable cardiac monitors in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome at low risk of sudden cardiac death. Cardiology 2020;145: 413–420.

- Scrocco C, Ben-Haim Y, Devine B, Tome-Esteban M, Papadakis M, Sharma S, et al. Role of subcutaneous implantable loop recorder for the diagnosis of arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome: a United Kingdom single-center experience. Heart Rhythm

2022;19:70–78.

1000. Sieira J, Brugada P. Brugada syndrome: defining the risk in asymptomatic patients. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2016;5:164–169. - Nishizaki M, Sakurada H, Yamawake N, Ueda-Tatsumoto A, Hiraoka M. Low risk for arrhythmic events in asymptomatic patients with drug-induced type 1 ECG. Do patients with drug-induced Brugada type ECG have poor prognosis? (Con). Circ J 2010;74:2464–2473.

- Conte G, de Asmundis C, Sieira J, Ciconte G, Di Giovanni G, Chierchia G-B, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of early repolarization pattern and QRS-fragmentation in high-risk patients with Brugada syndrome. Circ J 2016;80: 2109–2116.

- Kataoka N, Mizumaki K, Nakatani Y, Sakamoto T, Yamaguchi Y, Tsujino Y, et al. Paced QRS fragmentation is associated with spontaneous ventricular fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1497–1503.

- Probst V, Goronflot T, Anys S, Tixier R, Briand J, Berthome P, et al. Robustness and relevance of predictive score in sudden cardiac death for patients with Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1687–1695.

- Honarbakhsh S, Providencia R, Garcia-Hernandez J, Martin CA, Hunter RJ, Lim WY, et al. A primary prevention clinical risk score model for patients with Brugada syndrome (BRUGADA-RISK). JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:210–222.

- Andorin A, Gourraud J-B, Mansourati J, Fouchard S, le Marec H, Maury P, et al. The QUIDAM study: hydroquinidine therapy for the management of Brugada syndrome patients at high arrhythmic risk. Heart Rhythm 2017;14:1147–1154.

- Belhassen B, Rahkovich M, Michowitz Y, Glick A, Viskin S. Management of Brugada syndrome: thirty-three-year experience using electrophysiologically guided therapy with class 1A antiarrhythmic drugs. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8: 1393–1402.

- Ohgo T, Okamura H, Noda T, Satomi K, Suyama K, Kurita T, et al. Acute and chronic management in patients with Brugada syndrome associated with electrical storm of ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2007;4:695–700. 1009. Nademanee K, Raju H, de Noronha SV, Papadakis M, Robinson L, Rothery S, et al. Fibrosis, connexin-43, and conduction abnormalities in the Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1976–1986.

1010. Nademanee K, Haissaguerre M, Hocini M, Nogami A, Cheniti G, Duchateau J, et al. Mapping and ablation of ventricular fibrillation associated with early repolarization syndrome. Circulation 2019;140:1477–1490. - Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Chandanamattha P, Chaothawee L, Ariyachaipanich A, Jirasirirojanakorn K, et al. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation episodes in Brugada syndrome by catheter ablation over the anterior right ventricular outflow

tract epicardium. Circulation 2011;123:1270–1279. - Zhang P, Tung R, Zhang Z, Sheng X, Liu Q, Jiang R, et al. Characterization of the epicardial substrate for catheter ablation of Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:2151–2158.

1013. Haïssaguerre M, Extramiana F, Hocini M, Cauchemez B, Jaïs P, Cabrera JA, et al. Mapping and ablation of ventricular fibrillation associated with long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circulation 2003;108:925–928. - Brugada J, Pappone C, Berruezo A, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, Ciconte G, et al. Brugada syndrome phenotype elimination by epicardial substrate ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:1373–1381.

- Pappone C, Brugada J, Vicedomini G, Ciconte G, Manguso F, Saviano M, et al. Electrical substrate elimination in 135 consecutive patients with Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017;10:e005053.

- Yamagata K, Horie M, Aiba T, Ogawa S, Aizawa Y, Ohe T, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation of SCN5A mutation for the clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics of probands with Brugada syndrome: a Japanese multicenter registry. Circulation 2017;135:2255–2270.

- Haïssaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, Jesel L, Deisenhofer I, de Roy L, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med 2008;358: 2016–2023.

- Rosso R, Kogan E, Belhassen B, Rozovski U, Scheinman MM, Zeltser D, et al. J-point elevation in survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation and matched control subjects: incidence and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52: 1231–1238.

1019. Macfarlane PW, Antzelevitch C, Haissaguerre M, Huikuri HV, Potse M, Rosso R, et al. The early repolarization pattern: a consensus paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66:470–477.

1020. Tikkanen JT, Anttonen O, Junttila MJ, Aro AL, Kerola T, Rissanen HA, et al. Long-term outcome associated with early repolarization on electrocardiography. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2529–2537. - Sinner MF, Reinhard W, Müller M, Beckmann B-M, Martens E, Perz S, et al. Association of early repolarization pattern on ECG with risk of cardiac and allcause mortality: a population-based prospective cohort study (MONICA/ KORA). PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000314.

- Nunn LM, Bhar-Amato J, Lowe MD, Macfarlane PW, Rogers P, McKenna WJ, et al. Prevalence of J-point elevation in sudden arrhythmic death syndrome families. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:286–290.

- Watanabe H, Nogami A, Ohkubo K, Kawata H, Hayashi Y, Ishikawa T, et al. Electrocardiographic characteristics and SCN5A mutations in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation associated with early repolarization. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4:874–881.

- Chauveau S, Janin A, Till M, Morel E, Chevalier P, Millat G. Early repolarization syndrome caused by de novo duplication of KCND3 detected by next-generation sequencing. HeartRhythm Case Rep 2017;3:574–578.

- Takayama K, Ohno S, Ding W-G, Ashihara T, Fukumoto D, Wada Y, et al. A de novo gain-of-function KCND3 mutation in early repolarization syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2019;16:1698–1706.

- Rosso R, Glikson E, Belhassen B, Katz A, Halkin A, Steinvil A, et al. Distinguishing ‘benign’ from ‘malignant early repolarization’: the value of the ST-segment morphology. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:225–229.

- Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Anttonen O, Aro AL, Luttinen S, Kerola T, et al. Early repolarization: electrocardiographic phenotypes associated with favorable longterm outcome. Circulation 2011;123:2666–2673.

- Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Mower M, Likittanasombat K, Krittayapong R, Bhuripanyo K, et al. Defibrillator versus beta-blockers for unexplained Death in Thailand (DEBUT): a randomized clinical trial. Circulation 2003;107:2221–2226.

1029. Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Pharmacological and device approach to therapy of inherited cardiac diseases associated with cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death. J Electrocardiol 2000;33:41–47. - Haïssaguerre M, Sacher F, Nogami A, Komiya N, Bernard A, Probst V, et al. Characteristics of recurrent ventricular fibrillation associated with inferolateral early repolarization role of drug therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:612–619.

- Aizawa Y, Chinushi M, Hasegawa K, Naiki N, Horie M, Kaneko Y, et al. Electrical storm in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation is associated with early repolarization. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1015–1019.

- Patocskai B, Barajas-Martinez H, Hu D, Gurabi Z, Koncz I, Antzelevitch C. Cellular and ionic mechanisms underlying the effects of cilostazol, milrinone, and isoproterenol to suppress arrhythmogenesis in an experimental model of early repolarization syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1326–1334.

1033. Nam G-B, Kim Y-H, Antzelevitch C. Augmentation of J waves and electrical storms in patients with early repolarization. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2078–2079.

1034. Rodríguez-Capitán J, Fernández-Meseguer A, García-Pinilla JM, Calvo-Bonacho E, Jiménez-Navarro M, García-Margallo T, et al. Frequency of different electrocardiographic abnormalities in a large cohort of Spanish workers. Europace 2017; 19:1855–1863. - Sun G-Z, Ye N, Chen Y-T, Zhou Y, Li Z, Sun Y-X. Early repolarization pattern in the general population: prevalence and associated factors. Int J Cardiol 2017;230:614–618.

1036. Wu S-H, Lin X-X, Cheng Y-J, Qiang C-C, Zhang J. Early repolarization pattern and risk for arrhythmia death: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:645–650. - Malhi N, So PP, Cheung CC, Laksman ZWM, Healey JS, Chauhan VS, et al. Early repolarization pattern inheritance in the cardiac arrest survivors with preserved ejection fraction registry (CASPER). JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:1473–1479.

- Sinner MF, Porthan K, Noseworthy PA, Havulinna AS, Tikkanen JT, Müller-Nurasyid M, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of the electrocardiographic early repolarization pattern. Heart Rhythm 2012;9: 1627–1634.

- Adhikarla C, Boga M, Wood AD, Froelicher VF. Natural history of the electrocardiographic pattern of early repolarization in ambulatory patients. Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1831–1835.

- Mahida S, Derval N, Sacher F, Leenhardt A, Deisenhofer I, Babuty D, et al. Role of electrophysiological studies in predicting risk of ventricular arrhythmia in early repolarization syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:151–159.

- Aizawa Y, Sato A, Watanabe H, Chinushi M, Furushima H, Horie M, et al. Dynamicity of the J-wave in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation with a special reference to pause-dependent augmentation of the J-wave. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59: 1948–1953.

1042. Priori SG, Mazzanti A, Santiago DJ, Kukavica D, Trancuccio A, Kovacic JC. Precision medicine in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: JACC focus seminar 5/5. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:2592–2612. - Bezzina CR, Lahrouchi N, Priori SG. Genetics of sudden cardiac death. Circ Res

2015;116:1919–1936. - Kimura H, Zhou J, Kawamura M, Itoh H, Mizusawa Y, Ding W-G, et al. Phenotype variability in patients carrying KCNJ2 mutations. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2012;5: 344–353.

- Priori SG, Napolitano C, Memmi M, Colombi B, Drago F, Gasparini M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2002;106:69–74.

- Krahn AD, Gollob M, Yee R, Gula LJ, Skanes AC, Walker BD, et al. Diagnosis of unexplained cardiac arrest: role of adrenaline and procainamide infusion. Circulation 2005;112:2228–2234.

- Hayashi M, Denjoy I, Extramiana F, Maltret A, Buisson NR, Lupoglazoff J-M, et al. Incidence and risk factors of arrhythmic events in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2009;119:2426–2434.

- Leren IS, Saberniak J, Majid E, Haland TF, Edvardsen T, Haugaa KH. Nadolol decreases the incidence and severity of ventricular arrhythmias during exercise stress testing compared with β1-selective β-blockers in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:433–440.

- Peltenburg PJ, Kallas D, Bos JM, Lieve KVV, Franciosi S, Roston TM, et al. An international multicenter cohort study on β-blockers for the treatment of symptomatic children with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2022;145:333–344.

- van der Werf C, Nederend I, Hofman N, van Geloven N, Ebink C, Frohn-Mulder IME, et al. Familial evaluation in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: disease penetrance and expression in cardiac ryanodine receptor mutation-carrying relatives. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012;5:748–756.

- Watanabe H, Chopra N, Laver D, Hwang HS, Davies SS, Roach DE, et al. Flecainide prevents catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice and humans. Nat Med 2009;15:380–383.

- Wang G, Zhao N, Zhong S, Wang Y, Li J. Safety and efficacy of flecainide for patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16961.

- van der Werf C, Kannankeril PJ, Sacher F, Krahn AD, Viskin S, Leenhardt A, et al. Flecainide therapy reduces exercise-induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:2244–2254.

- Padfield GJ, AlAhmari L, Lieve KVV, AlAhmari T, Roston TM, Wilde AA, et al. Flecainide monotherapy is an option for selected patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia intolerant of β-blockade. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13:609–613.

1055. Roses-Noguer F, Jarman JWE, Clague JR, Till J. Outcomes of defibrillator therapy in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2014;11: 58–66. - De Ferrari GM, Dusi V, Spazzolini C, Bos JM, Abrams DJ, Berul CI, et al. Clinical management of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: the role of left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Circulation 2015;131:2185–2193.

- Roston TM, Jones K, Hawkins NM, Bos JM, Schwartz PJ, Perry F, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: a systematic review. Heart Rhythm 2018;15:1791–1799.

- van der Werf C, Lieve KV, Bos JM, Lane CM, Denjoy I, Roses-Noguer F, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in previously undiagnosed patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia resuscitated from sudden cardiac arrest. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2953–2961.

- Leenhardt A, Lucet V, Denjoy I, Grau F, Ngoc DD, Coumel P. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children. A 7-year follow-up of 21 patients. Circulation 1995;91:1512–1519.

- Kannankeril PJ, Moore JP, Cerrone M, Priori SG, Kertesz NJ, Ro PS, et al. Efficacy of flecainide in the treatment of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:759–766.

- Gollob MH, Redpath CJ, Roberts JD. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:802–812.

- Thorsen K, Dam VS, Kjaer-Sorensen K, Pedersen LN, Skeberdis VA, Jurevičius J, et al. Loss-of-activity-mutation in the cardiac chloride-bicarbonate exchanger AE3 causes short QT syndrome. Nat Commun 2017;8:1696.

- Mazzanti A, Kanthan A, Monteforte N, Memmi M, Bloise R, Novelli V, et al. Novel insight into the natural history of short QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63: 1300–1308.

- Dhutia H, Malhotra A, Parpia S, Gabus V, Finocchiaro G, Mellor G, et al. The prevalence and significance of a short QT interval in 18 825 low-risk individuals including athletes. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:124–129.

- Gallagher MM, Magliano G, Yap YG, Padula M, Morgia V, Postorino C, et al. Distribution and prognostic significance of QT intervals in the lowest half centile in 12,012 apparently healthy persons. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:933–935.

- Anttonen O, Junttila MJ, Rissanen H, Reunanen A, Viitasalo M, Huikuri HV. Prevalence and prognostic significance of short QT interval in a middle-aged Finnish population. Circulation 2007;116:714–720.

- Kobza R, Roos M, Niggli B, Abächerli R, Lupi GA, Frey F, et al. Prevalence of long and short QT in a young population of 41,767 predominantly male Swiss conscripts. Heart Rhythm 2009;6:652–657.

- Giustetto C, Schimpf R, Mazzanti A, Scrocco C, Maury P, Anttonen O, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with short QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:587–595

- El-Battrawy I, Besler J, Liebe V, Schimpf R, Tülümen E, Rudic B, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with short QT syndrome: clinical profile and outcome. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e010073.

- Mazzanti A, Maragna R, Vacanti G, Kostopoulou A, Marino M, Monteforte N, et al. Hydroquinidine prevents life-threatening arrhythmic events in patients with short QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:3010–3015.

- El-Battrawy I, Besler J, Li X, Lan H, Zhao Z, Liebe V, et al. Impact of antiarrhythmic drugs on the outcome of short QT syndrome. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:771.

- Malik M. Drug-induced QT/QTc interval shortening: lessons from drug-induced QT/QTc prolongation. Drug Saf 2016;39:647–659.

- Giustetto C, Scrocco C, Schimpf R, Maury P, Mazzanti A, Levetto M, et al. Usefulness of exercise test in the diagnosis of short QT syndrome. Europace2015;17:628–634.

- Mason JW, Ramseth DJ, Chanter DO, Moon TE, Goodman DB, Mendzelevski B. Electrocardiographic reference ranges derived from 79,743 ambulatory subjects. J Electrocardiol 2007;40:228–234.

- Bun S-S, Maury P, Giustetto C, Deharo J-C. Electrical storm in short-QT syndrome successfully treated with Isoproterenol. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012; 23:1028–1030