TS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

8.1. Thực hiện chăm sóc thay đổi

Một cách tiếp cận đa ngành được ủng hộ để cải thiện việc triển khai AF-CARE động học (xem Hình 2); mặc dù có khả năng tốn nhiều nguồn lực, nhưng cách này được ưu tiên hơn các phương pháp đơn giản hơn hoặc mang tính cơ hội hơn. Ví dụ, trong một thử nghiệm thực tế (pragmatic) đối với 47 333 bệnh nhân AF được xác định thông qua các yêu cầu bồi thường bảo hiểm y tế, không có sự khác biệt nào trong việc bắt đầu OAC sau 1 năm ở những bệnh nhân được phân ngẫu nhiên vào một lần gửi thư duy nhất về giáo dục bệnh nhân và bác sĩ lâm sàng, so với những bệnh nhân trong nhóm chăm sóc thông thường.[713] Đối với việc phối hợp chăm sóc, có một vai trò cốt lõi dành cho các bác sĩ tim mạch, bác sĩ đa khoa, điều dưỡng chuyên khoa và dược sĩ.[714] Nếu cần và tùy thuộc vào nguồn lực tại địa phương, những người khác cũng có thể tham gia (bác sĩ phẫu thuật tim, bác sĩ vật lý trị liệu, bác sĩ thần kinh, bác sĩ tâm lý và các chuyên gia y tế liên quan khác). Người ta ủng hộ mạnh mẽ rằng một thành viên cốt cán trong nhóm sẽ phối hợp chăm sóc và các thành viên khác trong nhóm sẽ tham gia theo nhu cầu của từng bệnh nhân trong suốt quá trình AF của họ.

Một số mô hình tổ chức chăm sóc tích hợp cho AF đã được đánh giá, nhưng thành phần nào hữu ích nhất vẫn chưa rõ ràng. Một số mô hình bao gồm một nhóm đa ngành,[715,716] trong khi những mô hình khác do y tá chỉ đạo [79,122,124,717] hoặc bác sĩ tim mạch chỉ đạo.[79,122,124,717] Một số mô hình đã công bố sử dụng hệ thống hỗ trợ quyết định bằng máy tính hoặc các ứng dụng sức khỏe điện tử.[79,122,715,718] Đánh giá trong RCT đã chứng minh kết quả hỗn hợp do nhiều phương pháp được thử nghiệm và sự khác biệt trong chăm sóc khu vực. Một số nghiên cứu báo cáo những cải thiện đáng kể về việc tuân thủ chống đông máu, tử vong do tim mạch và nhập viện so với tiêu chuẩn chăm sóc. [121–123] Tuy nhiên, thử nghiệm RACE 4 (Chương trình chăm sóc mãn tính tích hợp tại Phòng khám AF chuyên khoa so với Chăm sóc thông thường ở bệnh nhân rung nhĩ), gồm 1375 bệnh nhân, đã không chứng minh được tính ưu việt của việc chăm sóc do điều dưỡng viên chỉ đạo so với việc chăm sóc thông thường.[79] Các nghiên cứu mới về các thành phần và mô hình tối ưu để cung cấp các phương pháp tiếp cận chăm sóc tích hợp trong thực hành thường quy vẫn đang được tiến hành (ACTRN 12616001109493, NC T03924739)

8.2. Cải thiện việc tuân thủ điều trị

Những tiến bộ trong việc chăm sóc bệnh nhân AF chỉ có thể có hiệu quả nếu có các công cụ phù hợp để hỗ trợ việc thực hiện phác đồ điều trị.[719] Một số yếu tố liên quan đến việc thực hiện chăm sóc tối ưu ở cấp độ: (i) từng bệnh nhân (văn hóa, suy giảm nhận thức và trạng thái tâm lý); (ii) phương pháp điều trị (tính phức tạp, tác dụng phụ, dùng nhiều loại thuốc, tác động đến cuộc sống hàng ngày và chi phí); (iii) hệ thống chăm sóc sức khỏe (tiếp cận điều trị và phương pháp tiếp cận đa ngành); và (iv) chuyên gia chăm sóc sức khỏe (kiến thức, nhận thức về các hướng dẫn, chuyên môn và kỹ năng giao tiếp). Một phương pháp tiếp cận hợp tác đối với việc chăm sóc bệnh nhân, dựa trên việc ra quyết định chung và các mục tiêu phù hợp với nhu cầu của từng bệnh nhân, là rất quan trọng trong việc thúc đẩy bệnh nhân tuân thủ liên tục phác đồ điều trị đã thỏa thuận. [720] Ngay cả khi việc điều trị có vẻ khả thi đối với từng cá nhân, bệnh nhân thường không được tiếp cận thông tin đáng tin cậy và cập nhật về rủi ro và lợi ích của các lựa chọn điều trị khác nhau và do đó không được trao quyền để tự quản lý. Có thể khuyến khích ý thức sở hữu thúc đẩy việc đạt được các mục tiêu chung thông qua việc sử dụng các chương trình giáo dục, trang web (như https://afibmatters.org), các công cụ dựa trên ứng dụng và các giao thức điều trị được thiết kế riêng có tính đến các yếu tố giới tính, dân tộc, kinh tế xã hội, môi trường và công việc. Ngoài ra, các công cụ thực tế (ví dụ: lịch trình, ứng dụng, tờ rơi, lời nhắc, hộp đựng thuốc) có thể giúp triển khai điều trị trong cuộc sống hàng ngày. [721,722] Việc các thành viên của nhóm đa ngành xem xét thường xuyên giúp phát triển một chế độ quản lý linh hoạt và có khả năng đáp ứng mà bệnh nhân sẽ thấy dễ tuân theo hơn.

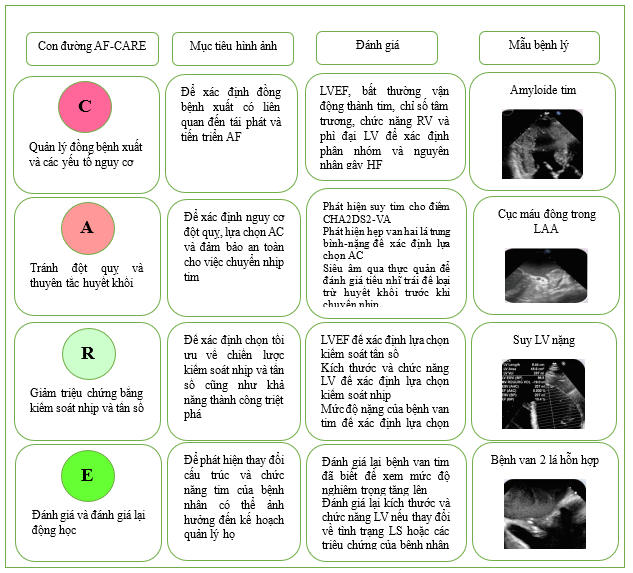

8.3. Hình ảnh tim

TTE là một tài sản có giá trị trên tất cả bốn lĩnh vực AF-CARE khi có những thay đổi về tình trạng lâm sàng của từng bệnh nhân (Hình 13).[723–725] Các phát hiện chính cần xem xét từ siêu âm tim là bất kỳ bệnh tim cấu trúc nào (ví dụ như bệnh van tim hoặc phì đại thất trái), suy giảm chức năng thất trái (tâm thu và/hoặc tâm trương để phân loại phân nhóm suy tim), giãn nhĩ trái và rối loạn chức năng tim phải.[59,67,726] Để chống lại tình trạng bất thường khi bị AF, việc đo các chu kỳ tim theo hai khoảng RR tương tự có thể cải thiện giá trị của các thông số so với việc tính trung bình tuần tự các chu kỳ tim. [723,727] Có thể cần TTE tương phản hoặc các phương thức hình ảnh thay thế khi chất lượng hình ảnh kém và cần định lượng chức năng tâm thu thất trái để đưa ra quyết định về kiểm soát nhịp tim hoặc tần số. Các kỹ thuật hình ảnh tim khác, chẳng hạn như cộng hưởng từ tim (CMR), CT, TOE và hình ảnh hạt nhân có thể có giá trị khi: (i) chất lượng TTE không tối ưu cho mục đích chẩn đoán; (ii) cần thông tin bổ sung về cấu trúc, nền tảng hoặc chức năng; và (iii) để hỗ trợ các quyết định về các thủ thuật can thiệp (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Hình S1).[59,724,725,728] Cũng như TTE, các loại hình ảnh tim khác có thể trở nên thách thức trong bối cảnh AF không đều hoặc tần số tim nhanh, đòi hỏi phải sửa đổi kỹ thuật cụ thể khi thu thập các chuỗi có cổng ECG.[729–731]

8.4. Các biện pháp kết quả do bệnh nhân báo cáo

Bệnh nhân AF có chất lượng cuộc sống thấp hơn so với dân số nói chung.[732] Cải thiện chất lượng cuộc sống và tình trạng chức năng nên đóng vai trò quan trọng trong việc đánh giá và đánh giá lại các quyết định điều trị (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S26). [36] Các biện pháp kết quả do bệnh nhân báo cáo có giá trị để đo lường chất lượng cuộc sống, tình trạng chức năng, các triệu chứng và gánh nặng điều trị cho bệnh nhân AF theo thời gian. [55,733–735] Các biện pháp kết quả do bệnh nhân báo cáo đang đóng vai trò ngày càng tăng trong các thử nghiệm lâm sàng để đánh giá thành công của điều trị; tuy nhiên, chúng vẫn chưa được sử dụng hết.[736,737] Chúng có thể được chia thành các công cụ chung hoặc cụ thể cho từng bệnh, trong đó công cụ sau giúp cung cấp thông tin chi tiết về các tác động liên quan đến AF. [738] Tuy nhiên, tình trạng đa bệnh vẫn có thể làm nhiễu độ nhạy của tất cả các PROM, ảnh hưởng đến mối liên quan với các số liệu đã thiết lập khác về hiệu suất điều trị như class triệu chứng mEHRA và natriuretic peptide.[48] Các nghiên cứu can thiệp đã chứng minh mối liên quan giữa việc cải thiện điểm PROM và giảm gánh nặng và triệu chứng AF. [48,738] Các bảng câu hỏi cụ thể về rung nhĩ bao gồm AF 6 (AF6),[739] Ảnh hưởng của rung nhĩ đến chất lượng cuộc sống (AFEQT),[740] Bản câu hỏi về chất lượng cuộc sống do rung nhĩ (AFQLQ), [741] Chất lượng cuộc sống do rung nhĩ (AF-QoL), [742] và Chất lượng cuộc sống trong rung nhĩ (QLAF). [743] Các đặc tính đo lường của hầu hết các công cụ này đều thiếu sự xác thực đầy đủ. [49] Nhóm làm việc của Liên đoàn quốc tế về đo lường kết quả sức khỏe (ICHOM) khuyến cáo sử dụng AFEQT PROM hoặc một bảng câu hỏi về triệu chứng được gọi là Thang đo mức độ nghiêm trọng của rung nhĩ (AFSS) để đo khả năng chịu đựng khi gắng sức và tác động của các triệu chứng trong AF. [744] Thông qua việc sử dụng rộng rãi hơn các biện pháp đo lường kinh nghiệm của bệnh nhân, có một cơ hội ở cấp độ tổ chức để cải thiện chất lượng chăm sóc dành cho bệnh nhân mắc AF. [49–55]

Bảng khuyến cáo 23 — Các khuyến cáo để cải thiện trải nghiệm của bệnh nhân (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 23)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Đánh giá chất lượng chăm sóc và xác định các cơ hội cải thiện điều trị AF nên được các nhà chuyên môn và tổ chức xem xét để cải thiện trải nghiệm của bệnh nhân. [49–55] |

IIa |

B |

AF: rung nhĩ.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

Hình 13. Sự liên quan của siêu âm tim trong con đường AF-CARE.

AF: rung nhĩ; AF-CARE: A: rung nhĩ—[C] Quản lý bệnh đi kèm và yếu tố nguy cơ, [A] Tránh đột quỵ và huyết khối tắc mạch, [R] Giảm các triệu chứng bằng cách kiểm soát nhịp tim và tần số, [E] Đánh giá và đánh giá lại động học; CHA2DS2-VA: suy tim sung huyết, tăng huyết áp, tuổi ≥75 (2 điểm), đái tháo đường, đột quỵ/thiếu máu cục bộ thoáng qua/huyết khối tắc mạch động mạch trước đó (2 điểm), bệnh mạch máu, tuổi 65–74; LAA: tiểu nhĩ; LV, thất trái.

9. Con đường AF-CARE trong các bối cảnh lâm sàng cụ thể

Các phần sau đây trình bày chi tiết các bối cảnh lâm sàng cụ thể cách tiếp cận AF-CARE có thể khác nhau. Trừ khi được thảo luận đặc biệt, các biện pháp để [C] quản lý bệnh đi kèm và yếu tố nguy cơ, [A] tránh đột quỵ và huyết khối tắc mạch, [R] kiểm soát tần số và nhịp tim, và [E] đánh giá và đánh giá lại động lực nên tuân theo các con đường tiêu chuẩn được giới thiệu trong Phần 4

9.1. AF-CARE ở các bệnh nhân không ổn định

Bệnh nhân không ổn định với AF gồm những người có tình trạng huyết động không ổn định do rồi loạn nhịp tim hoặc tình trạng tim cấp tính, và những bệnh nhân bị bệnh nặng phát triển AF (nhiễm trùng huyết, chấn thương, phẫu thuật và đặc biệt là phẫu thuật liên quan đến ung thư). Các tình trạng như nhiễm trùng huyết, kích thích quá mức adrenergic và rối loạn điện giải góp phần gây khởi phát và tái phát AF ở những bệnh nhân này. Nhịp xoang tự phục hồi đã được báo cáo ở 83% trong vòng 48 giờ đầu tiên sau khi điều trị thích hợp nguyên nhân cơ bản. [551,745]

Chuyển nhịp bằng điện khẩm cấp vẫn được coi là phương pháp điều trị lựa chọn đầu tiên nếu nhịp xoang được cho là có lợi, mặc dù hạn chế là có tỷ lệ tái phát ngay lập tức cao.[746] Amiodarone là lựa chọn thứ hai vì tác dụng chậm của nó; tuy nhiên, nó có thể là một giải pháp thay thế phù hợp trong bối cảnh cấp tính.[747,748] Trong một nghiên cứu theo dõi đa trung tâm được thực hiện tại Vương quốc Anh và Hoa Kỳ, amiodarone và thuốc chẹn beta có hiệu quả tương tự nhau trong việc kiểm soát nhịp tim ở những bệnh nhân chăm sóc đặc biệt và vượt trội hơn thuốc chẹn kênh canxi và digoxin. [749] Thuốc chẹn beta tác dụng cực ngắn và có tính chọn lọc cao landiolol có thể kiểm soát an toàn AF nhanh ở những bệnh nhân có phân suất tống máu thấp và suy tim mất bù cấp tính, với tác động hạn chế đến khả năng co bóp cơ tim hoặc huyết áp. [477,750,751]

9.2. AF-CARE trong hội chứng mạch vành cấp

Tỷ lệ AF trong hội chứng vành cấp (ACS) dao động từ 2% đến 23%.[752] Nguy cơ AF mới khởi phát tăng 60%–77% ở những bệnh nhân bị MI, [753] và AF có thể liên quan đến tăng nguy cơ nhồi máu cơ tim ST chênh lên (STEMI) hoặc ACS không phải STEMI. [754] Nhìn chung, 10%–15% bệnh nhân AF trải qua can thiệp qua da (PCI) để điều trị CAD. [755] Ngoài ra, AF là tác nhân gây nhồi máu cơ tim type 2 phổ biến. [756] Các nghiên cứu quan sát cho thấy những bệnh nhân mắc cả ACS và AF ít có khả năng được điều trị chống huyết khối thích hợp [757] và có nhiều khả năng gặp phải các kết quả bất lợi. [758] Quản lý quanh thủ thuật cho bệnh nhân bị ACS hoặc hội chứng vành mạn tính (CCS) được nêu chi tiết trong Hướng dẫn ESC năm 2023 về quản lý hội chứng vành cấp và Hướng dẫn ESC năm 2024 về quản lý hội chứng vành mạn tính. [759,760]

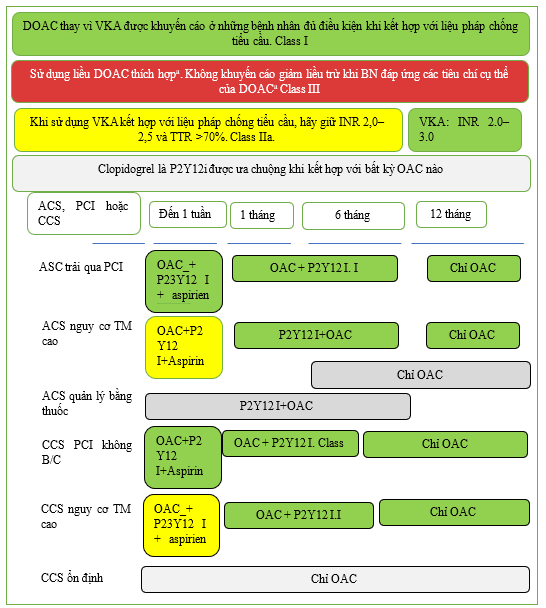

Sự kết hợp AF với ACS là lĩnh vực mà việc sử dụng nhiều loại thuốc chống huyết khối thường được chỉ định nhất, bao gồm thuốc chống tiểu cầu cộng với OAC (Hình 14) (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S27). Có một xu hướng chung là giảm thời gian dùng DAPT để giảm chảy máu; tuy nhiên, điều này có thể làm tăng các biến cố thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối stent. [761,762] Ở ACS, có nguy cơ cao bị huyết khối xơ vữa động mạch chủ yếu do tiểu cầu và do đó là các biến cố thiếu máu cục bộ động mạch vành. Các hội chứng vành cấp được điều trị bằng PCI cần dùng DAPT để cải thiện tiên lượng ngắn hạn và dài hạn. Do đó, phác đồ chống huyết khối ba thuốc quanh thủ thuật bao gồm OAC, aspirin và thuốc ức chế P2Y12 nên là chiến lược mặc định cho hầu hết bệnh nhân. Các biến cố huyết khối lớn so với nguy cơ chảy máu lớn cần được cân bằng khi kê đơn liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu và OAC sau giai đoạn cấp tính và/hoặc sau PCI. Sự kết hợp của OAC (tốt nhất là DOAC) và thuốc ức chế P2Y12 dẫn đến ít chảy máu lớn hơn liệu pháp ba thuốc bao gồm aspirin. Clopidogrel là thuốc ức chế P2Y12 được ưu tiên, vì bằng chứng về ticagrelor và prasugrel ít rõ ràng hơn với nguy cơ chảy máu cao hơn. [763–769] Các thử nghiệm đang diễn ra sẽ bổ sung thêm kiến thức của chúng ta về việc kết hợp an toàn DOAC với thuốc chống tiểu cầu (NCT04981041, NCT04436978). Khi sử dụng VKA với thuốc chống tiểu cầu, có ý kiến đồng thuận là sử dụng phạm vi INR từ 2,0–2,5 để giảm nguy cơ chảy máu quá mức.

Liệu pháp ba thuốc ngắn hạn (≤1 tuần) được khuyến cáo cho tất cả bệnh nhân không bị tiểu đường sau ACS hoặc PCI. Trong các phân tích gộp của RCT, việc không dùng aspirin ở những bệnh nhân bị ACS đang trải qua PCI có khả năng gây ra tỷ lệ huyết khối do thiếu máu cục bộ/stent cao hơn, mà không ảnh hưởng đến đột quỵ mới mắc.[761,762,770–772] Không có thử nghiệm nào được cung cấp năng lượng cho các biến cố thiếu máu cục bộ. Tất cả bệnh nhân trong AUGUSTUS (một thử nghiệm lâm sàng có đối chứng ngẫu nhiên, giai thừa 2 × 2, nhãn mở để đánh giá tính an toàn của apixaban so với thuốc đối kháng vitamin k và aspirin so với giả dược aspirin ở những bệnh nhân bị AF và ACS hoặc PCI) được dùng aspirin cộng với thuốc ức chế P2Y12 trong thời gian trung bình là 6 ngày.[773] Vào cuối thử nghiệm, apixaban và thuốc ức chế P2Y12 không có aspirin là phác đồ điều trị tối ưu cho hầu hết bệnh nhân AF và ACS và/hoặc PCI, bất kể nguy cơ chảy máu và đột quỵ ban đầu của bệnh nhân.[774,775]

Nên cân nhắc liệu pháp ba thuốc kéo dài đến 1 tháng sau ACS/PCI ở những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ thiếu máu cục bộ cao, ví dụ như STEMI, huyết khối stent trước đó, các thủ thuật vành phức tạp và tình trạng tim không ổn định kéo dài, mặc dù những bệnh nhân này chưa được đại diện đầy đủ trong các RCT hiện có. [776] Ở những bệnh nhân AF bị ACS hoặc CCS và đái tháo đường đang được đặt stent động mạch vành, liệu pháp ba thuốc kéo dài với aspirin liều thấp, clopidogrel và OAC lên đến 3 tháng có thể có lợi nếu nguy cơ huyết khối lớn hơn nguy cơ chảy máu ở từng bệnh nhân.

Bằng chứng về ACS được điều trị mà không tái thông mạch còn hạn chế. Sáu đến 12 tháng dùng một thuốc chống tiểu cầu đơn lẻ thêm vào DOAC dài hạn thường là đủ và có thể giảm thiểu nguy cơ chảy máu.[760,764,774] Mặc dù không có so sánh trực tiếp giữa aspirin và clopidogrel, các nghiên cứu thường sử dụng clopidogrel. Ở những bệnh nhân có CCS ổn định trong hơn 12 tháng, liệu pháp duy nhất bằng DOAC là đủ và không cần liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu bổ sung

. [353] Ở những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ chảy máu đường tiêu hóa tiềm ẩn, việc sử dụng thuốc ức chế bơm proton là hợp lý trong quá trình điều trị chống huyết khối kết hợp, mặc dù bằng chứng ở bệnh nhân AF còn hạn chế. [437,777–779] Bệnh nhân mắc nhiều bệnh lý với ACS hoặc CCS cần đánh giá cẩn thận nguy cơ thiếu máu cục bộ và quản lý các yếu tố nguy cơ chảy máu có thể thay đổi, với quá trình đánh giá toàn diện để điều chỉnh liệu pháp chống huyết khối cho từng cá thể.

Bảng khuyến cáo 24 — Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân mắc hội chứng vành cấp hoặc đang trải qua can thiệp qua da (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 24)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Khuyến cáo chung cho bệnh nhân AF và chỉ định dùng liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu đồng thời | ||

| Đối với các kết hợp với liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu, DOAC được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân đủ điều kiện thay vì VKA để giảm nguy cơ chảy máu và ngăn ngừa huyết khối tắc mạch.[764,766] |

I |

A |

| Nên cân nhắc dùng rivaroxaban 15 mg một lần mỗi ngày thay vì rivaroxaban 20 mg một lần mỗi ngày khi kết hợp với liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu ở những bệnh nhân lo ngại về nguy cơ chảy máu hơn lo ngại về huyết khối stent hoặc đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ. [765] |

IIa |

B |

| Nên cân nhắc dùng dabigatran 110 mg hai lần mỗi ngày thay vì dabigatran 150 mg hai lần mỗi ngày khi kết hợp với liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu ở những bệnh nhân lo ngại về nguy cơ chảy máu hơn lo ngại về huyết khối stent hoặc đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ.[766] |

IIa

|

B |

| Cần cân nhắc liều dùng VKA được điều chỉnh cẩn thận với mục tiêu INR là 2,0–2,5 và TTR >70% khi kết hợp với liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu ở bệnh nhân AF để giảm nguy cơ chảy máu. |

IIa |

C |

| Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân AF có ACS | ||

| Nên ngừng sớm (≤1 tuần) aspirin và tiếp tục thuốc chống đông đường uống (tốt nhất là DOAC) với thuốc ức chế P2Y12 (tốt nhất là clopidogrel) trong tối đa 12 tháng ở những bệnh nhân AF bị ACS

đang trải qua PCI không biến chứng để tránh chảy máu lớn, nếu nguy cơ huyết khối thấp hoặc nguy cơ chảy máu cao. [764–767] |

I |

A |

| Cần cân nhắc liệu pháp ba thuốc với aspirin, clopidogrel và thuốc chống đông đường uống trong hơn 1 tuần sau ACS ở những bệnh nhân AF khi nguy cơ thiếu máu cục bộ lớn hơn nguy cơ chảy máu, với tổng thời gian (≤1 tháng) được quyết định theo đánh giá các nguy cơ này và ghi chép rõ ràng về kế hoạch điều trị khi xuất viện. [776] |

IIa |

C |

| Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân AF đang trải qua PCI | ||

| Sau PCI không biến chứng, nên ngừng sớm (≤1 tuần) aspirin và tiếp tục dùng thuốc chống đông đường uống và thuốc ức chế P2Y12 (tốt nhất là clopidogrel) trong tối đa 6 tháng để tránh chảy máu lớn, nếu nguy cơ thiếu máu cục bộ thấp. [763–766,776,780] |

I |

A |

| Nên cân nhắc liệu pháp ba thuốc gồm aspirin, clopidogrel và thuốc chống đông đường uống trong thời gian dài hơn 1 tuần sau PCI khi nguy cơ huyết khối stent lớn hơn nguy cơ chảy máu, với tổng thời gian (≤1 tháng) được quyết định theo đánh giá các rủi ro này và tài liệu rõ ràng.[776] |

IIa |

B |

| Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân AF mắc bệnh mạch vành hoặc mạch máu mạn tính | ||

| Liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu kéo dài quá 12 tháng không được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân ổn định mắc bệnh mạch vành hoặc mạch máu mạn tính được điều trị bằng thuốc chống đông đường uống, do thiếu hiệu quả và để tránh chảy máu nghiêm trọng. [353,781,782]

III B |

III |

B |

ACS: hội chứng vành cấp; AF: rung nhĩ; DOAC: thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp; INR: tỷ lệ prothrombin chuẩn hóa quốc tế; PCI: can thiệp qua da; TTR: thời gian trong phạm vi điều trị; VKA: thuốc đối kháng vitamin K.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

Hình 14. Liệu pháp chống huyết khối ở bệnh nhân AF và hội chứng mạch vành cấp hoặc mạn tính.

ACS: hội chứng mạch vành cấp; CCS: hội chứng mạch vành mạn tính; DOAC: thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp; INR: tỷ lệ prothrombin chuẩn hóa quốc tế; OAC: thuốc chống đông đường uống; P2Y12i: thuốc chống tiểu cầu ức chế thụ thể P2Y12 (clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor); PCI: can thiệp qua da; TTR: thời gian trong phạm vi điều trị; VKA: thuốc đối kháng vitamin K. Sơ đồ áp dụng cho những bệnh nhân có chỉ định điều trị chống đông đường uống. a. Cần sử dụng liều chuẩn đầy đủ của DOAC trừ khi bệnh nhân đáp ứng các tiêu chí giảm liều (Bảng 11). Khi sử dụng rivaroxaban hoặc dabigatran làm DOAC và lo ngại về nguy cơ chảy máu chiếm ưu thế hơn huyết khối stent hoặc đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ, nên cân nhắc giảm liều (lần lượt là 15 mg và 110 mg; Nhóm IIa). b. Ở những bệnh nhân bị đái tháo đường đang được đặt stent động mạch vành, việc kéo dài liệu pháp chống huyết khối ba thuốc trong tối đa 3 tháng có thể có giá trị nếu nguy cơ huyết khối lớn hơn nguy cơ chảy máu.

9.3. AF-CARE trong bệnh mạch máu

Bệnh động mạch ngoại biên (PAD) thường gặp ở những bệnh nhân bị AF, dao động từ 6,7% đến 14% bệnh nhân. [783,784] PAD biểu hiện có liên quan đến AF mới mắc. [785] PAD dự đoán tỷ lệ tử vong cao hơn ở những bệnh nhân bị AF và là yếu tố dự báo độc lập về đột quỵ ở những bệnh nhân không dùng OAC. [783,786] Những bệnh nhân bị bệnh động mạch chi dưới và AF cũng có tỷ lệ tử vong chung cao hơn và nguy cơ mắc các biến cố tim mạch lớn. [784,787,788] Cơ sở dữ liệu y tế công cộng của >40.000 bệnh nhân nhập viện vì PAD hoặc thiếu máu cục bộ chi nghiêm trọng cho thấy AF là yếu tố dự báo độc lập về tỷ lệ tử vong (HR, 1,46; 95% CI, 1,39–1,52) và đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ (HR, 1,63; 95% CI, 1,44–1,85) so với nhóm đối chứng phù hợp với khuynh hướng. [784] Tương tự như vậy, ở những bệnh nhân trải qua phẫu thuật cắt bỏ nội mạc động mạch cảnh hoặc đặt stent, sự hiện diện của AF có liên quan đến tỷ lệ tử vong cao hơn (OR, 1,59; 95% CI, 1,11–2,26). [789]

Chống đông máu đơn thuần thường là đủ trong giai đoạn bệnh mãn tính, với DOAC là tác nhân được ưu tiên mặc dù một phân tích RCT cho thấy nguy cơ chảy máu cao hơn so với warfarin. [790] Trong trường hợp tái thông mạch máu nội mạch gần đây, nên cân nhắc thời gian kết hợp với liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu đơn lẻ, cân nhắc nguy cơ chảy máu và huyết khối và giữ thời gian điều trị chống huyết khối kết hợp càng ngắn càng tốt (dao động từ 1 tháng đối với ngoại vi [791] và 90 ngày đối với các thủ thuật can thiệp thần kinh). [792]

9.4. AF-CARE trong đột quỵ cấp tính hoặc xuất huyết nội sọ

9.4.1. Quản lý đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ cấp tính

Quản lý đột quỵ cấp tính ở bệnh nhân AF nằm ngoài phạm vi của các hướng dẫn này. Ở những bệnh nhân AF bị đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ cấp tính trong khi dùng OAC, liệu pháp cấp tính phụ thuộc vào phác đồ điều trị và cường độ của OAC. Việc quản lý nên được phối hợp do một nhóm bác sĩ thần kinh chuyên khoa theo các hướng dẫn có liên quan. [793]

9.4.2. Hướng dẫn hoặc hướng dẫn lại thuốc chống đông sau đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ

Thời điểm tối ưu để dùng OAC ở những bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ tắc mạch do tim cấp tính và AF vẫn chưa rõ ràng. Các thử nghiệm đối chứng ngẫu nhiên không thể cung cấp bất kỳ bằng chứng nào để hỗ trợ việc dùng thuốc chống đông hoặc heparin ở những bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ cấp tính trong vòng 48 giờ kể từ khi đột quỵ khởi phát. Điều này cho thấy nên dùng aspirin liều thấp cho tất cả bệnh nhân trong khoảng thời gian này. [794]

Hai thử nghiệm đã xem xét việc sử dụng liệu pháp DOAC sớm sau đột quỵ, không có sự khác biệt về kết quả lâm sàng so với kê đơn DOAC muộn. Thử nghiệm ELAN (Early versus Late initiation of direct oral Anticoagulants in post-ischaemic stroke patients with atrial fibrillatioN: Khởi đầu sớm so với muộn thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp ở bệnh nhân đột quỵ sau thiếu máu cục bộ có rung nhĩ) đã phân nhóm ngẫu nhiên 2013 bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ cấp tính và AF để sử dụng DOAC sớm nhãn mở (<48 giờ sau đột quỵ nhẹ/trung bình; ngày 6–7 sau đột quỵ lớn) so với kê đơn DOAC muộn hơn (ngày 3–4 sau đột quỵ nhẹ; ngày 6–7 sau đột quỵ vừa; ngày 12–14 sau đột quỵ lớn). Không có sự khác biệt đáng kể về kết quả huyết khối tắc mạch, chảy máu và tử vong do mạch máu sau 30 ngày (Nguy cơ chênh lệch sớm so với muộn, −1,18%; 95% CI, −2,84 đến 0,47). [795] Thử nghiệm TIMING (Timing of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke With Atrial Fibrillation: Thời điểm điều trị thuốc chống đông đường uống trong đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ cấp tính có rung nhĩ), một thử nghiệm tiêu chỉ được mù, nhắn mở trên cơ sở đăng ký, không thua kém hơn ngẫu nhiên ở 888 bệnh nhân trong vòng 72 giờ sau khi đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ đến thời điểm bắt đầu DOAC sớm (≤4 ngày) hoặc muộn (5–10 ngày). Việc sử dụng DOAC sớm không kém hơn so với chiến lược trì hoãn đối với biến cố huyết khối tắc mạch, chảy máu và tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân sau 90 ngày (chênh lệch nguy cơ, -1,79%; 95% CI, -5,31% đến 1,74%). [796] Hai thử nghiệm đang diễn ra sẽ cung cấp thêm hướng dẫn về thời điểm thích hợp nhất để điều trị DOAC sau đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ (NCT03759938, NCT03021928)

9.4.3. Giới thiệu hoặc tái giới thiệu thuốc chống đông máu sau đột quỵ xuất huyết

Hiện tại không có đủ bằng chứng để khuyến nghị liệu OAC có nên được bắt đầu hay bắt đầu lại sau ICH để bảo vệ chống lại nguy cơ cao bị đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ ở những bệnh nhân này (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S28). Dữ liệu từ hai thử nghiệm thí điểm có sẵn. Thử nghiệm APACHE-AF (Apixaban sau khi xuất huyết não liên quan đến thuốc chống đông máu ở những bệnh nhân bị rung nhĩ) là một thử nghiệm nhãn mở, ngẫu nhiên, có triển vọng với đánh giá điểm cuối được che giấu; 101 bệnh nhân sống sót sau 7–90 ngày sau ICH liên quan đến thuốc chống đông máu được phân ngẫu nhiên vào nhóm dùng apixaban hoặc không dùng OAC. Trong thời gian theo dõi trung bình 1,9 năm (222 người-năm), không có sự khác biệt nào về đột quỵ không tử vong hoặc tử vong do mạch máu, với tỷ lệ biến cố hàng năm là 12,6% khi dùng apixaban và 11,9% khi không dùng OAC (HR điều chỉnh, 1,05; 95% CI, 0,48–2,31; P = 0,90).797 SoSTART (Thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên về thuốc chống đông Start hoặc STop) là RCT nhãn mở trên 203 bệnh nhân bị AF sau khi xuất huyết não tự phát có triệu chứng. Bắt đầu dùng OAC không kém hơn so với việc tránh dùng OAC dài hạn (≥1 năm), với tỷ lệ tái phát ICH ở 8/101 (8%) so với 4/102 (4%) bệnh nhân (HR điều chỉnh, 2,42; 95% CI, 0,72–8,09). Tỷ lệ tử vong xảy ra ở 22/101 (22%) bệnh nhân trong nhóm OAC so với 11/102 (11%) bệnh nhân không dùng OAC. [798]

Cho đến khi các thử nghiệm bổ sung báo cáo về thách thức lâm sàng của thuốc chống đông sau ICH (NCT03950076, NCT03996772), nên áp dụng phương pháp tiếp cận đa ngành được cá nhân hóa do nhóm chuyên gia thần kinh học dẫn đầu.

9.5. AF-CARE cho AF do tác nhân kích thích

AF do tác nhân kích thích được định nghĩa là AF mới trong mối liên hệ trực tiếp của một yếu tố thúc đẩy và có khả năng hồi phục. Còn được gọi là AF ‘thứ cấp’, nhóm đặc nhiệm này thích thuật ngữ do tác nhân kích thích vì hầu như luôn có các yếu tố tiềm ẩn ở từng bệnh nhân có thể được hưởng lợi từ việc xem xét đầy đủ con đường AF-CARE. Tác nhân thúc đẩy phổ biến nhất làm lộ ra xu hướng AF là nhiễm trùng huyết cấp tính, trong đó tỷ lệ mắc AF nằm trong khoảng từ 9% đến 20% và có liên quan đến tiên lượng xấu hơn. [11–14] Mức độ viêm tương quan với tỷ lệ mắc AF, [799] điều này có thể giải thích một phần sự thay đổi rộng rãi giữa các nghiên cứu về tỷ lệ mắc cũng như tái phát AF. Dữ liệu dài hạn cho thấy AF do nhiễm trùng huyết tái phát sau khi xuất viện ở khoảng một phần ba đến một nửa số bệnh nhân.[12,800–807] Ngoài các tác nhân cấp tính khác có thể là nguyên nhân (như rượu [808,809] và sử dụng ma túy bất hợp pháp [810], nhiều tình trạng cũng liên quan đến tình trạng viêm mãn tính dẫn đến các kích thích bán cấp đối với AF (Bảng 14). Tác nhân cụ thể của một quy trình phẫu thuật được thảo luận trong Phần 9.6.

Sau khi đáp ứng các tiêu chuẩn chẩn đoán AF (xem Mục 3.2), việc quản lý AF do yếu tố kích hoạt được khuyến cáo tuân theo các nguyên tắc AF-CARE, với việc cân nhắc quan trọng các yếu tố nguy cơ tiềm ẩn và các bệnh đi kèm. Dựa trên dữ liệu hồi cứu và quan sát, bệnh nhân bị AF và AF do yếu tố kích hoạt có vẻ mang cùng nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch như bệnh nhân bị AF nguyên phát. [811,812] Trong giai đoạn cấp tính của nhiễm trùng huyết, bệnh nhân cho thấy hồ sơ nguy cơ-lợi ích không rõ ràng với liệu pháp chống đông máu. [813,814] Các nghiên cứu triển vọng về thuốc chống đông máu ở những bệnh nhân bị các cơn AF do yếu tố kích hoạt vẫn còn thiếu. [802,812,815] Thừa nhận rằng không có RCT nào có sẵn cụ thể trong nhóm dân số này để đánh giá AF do yếu tố kích hoạt, nên cân nhắc liệu pháp OAC dài hạn ở những bệnh nhân phù hợp bị AF do yếu tố kích hoạt có nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch cao, bắt đầu dùng OAC sau khi yếu tố kích hoạt cấp tính đã được điều chỉnh và cân nhắc lợi ích lâm sàng ròng dự kiến và sở thích của bệnh nhân đã được thông báo. Cũng như với bất kỳ quyết định nào về OAC, không phải tất cả bệnh nhân đều phù hợp với OAC, tùy thuộc vào các chống chỉ định tương đối và tuyệt đối và nguy cơ chảy máu lớn. Cách tiếp cận để kiểm soát nhịp tim và tỷ lệ sẽ phụ thuộc vào sự tái phát AF sau đó hoặc bất kỳ triệu chứng liên quan nào, và việc đánh giá lại nên được cá nhân hóa để tính đến tỷ lệ tái phát AF thường cao.

Bảng 14. Các tình trạng không liên quan đến tim có liên quan đến AF do kích hoạt

| Tình trạng cấp tính |

| Nhiễm trùng (do vi khuẩn và vi-rút) |

| Viêm màng ngoài tim, viêm cơ tim |

| Tình trạng cấp cứu (bỏng, chấn thương nghiêm trọng, sốc) |

| Uống rượu quá độ |

| Sử dụng ma túy, bao gồm methamphetamine, cocaine, thuốc phiện và cần sa |

| Các can thiệp, thủ thuật và phẫu thuật cấp tính |

| Rối loạn nội tiết (tuyến giáp, tuyến thượng thận, tuyến yên, các bệnh khác) |

| Các tình trạng mãn tính với tình trạng viêm và chất nền AF tăng cường |

| Các bệnh do miễn dịch (viêm khớp dạng thấp, lupus ban đỏ hệ thống, bệnh viêm ruột, bệnh celiac, bệnh vẩy nến, các bệnh khác) |

| Béo phì |

| Bệnh tắc nghẽn đường thở mãn tính |

| Ngưng thở khi ngủ do tắc nghẽn |

| Ung thư |

| Bệnh gan nhiễm mỡ |

| Căng thẳng |

| Rối loạn nội tiết (xem Mục 9.10) |

Bảng khuyến cáo 25 – Khuyến cáo cho AF do kích hoạt (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 25)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Khuyến cáo chung cho bệnh nhân AF và chỉ định dùng liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu đồng thời | ||

| Nên cân nhắc dùng thuốc chống đông đường uống dài hạn ở những bệnh nhân phù hợp với AF do tác nhân kích hoạt có nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch cao để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối tắc mạch toàn thân. [13,800,806,807,815] |

IIa |

C |

AF, rung nhĩ.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng

9.6. AF-CARE ở bệnh nhân sau phẫu thuật

AF quanh phẫu thuật mô tả sự khởi phát của loạn nhịp tim trong quá trình can thiệp đang diễn ra. AF sau phẫu thuật (POAF), được định nghĩa là AF mới khởi phát trong giai đoạn hậu phẫu ngay sau phẫu thuật, là một biến chứng thường gặp có tác động lâm sàng xảy ra ở 30%–50% bệnh nhân trải qua phẫu thuật tim [816–818] và ở 5%–30% bệnh nhân trải qua phẫu thuật không phải tim. Những thay đổi trong và sau phẫu thuật và các tác nhân kích hoạt AF cụ thể (gồm các biến chứng quanh phẫu thuật) và các yếu tố nguy cơ và bệnh đi kèm liên quan đến AF từ trước làm tăng nguy cơ mắc POAF.[819] Mặc dù các đợt POAF có thể tự chấm dứt, POAF có liên quan đến việc tăng 4–5 lần AF tái phát trong 5 năm tiếp theo [820,821] và là một yếu tố nguy cơ gây đột quỵ, nhồi máu cơ tim, suy tim và tử vong. [822–827] Các tác dụng phụ khác liên quan đến POAF bao gồm mất ổn định huyết động, thời gian nằm viện kéo dài, nhiễm trùng, biến chứng thận, chảy máu, tăng tử vong trong bệnh viện và chi phí chăm sóc sức khỏe cao hơn. [828–830]

Mặc dù nhiều chiến lược để ngăn ngừa POAF bằng điều trị trước hoặc điều trị bằng thuốc cấp tính đã được mô tả, nhưng vẫn thiếu bằng chứng từ các RCT lớn. Sử dụng propranolol hoặc carvedilol cộng với N-acetyl cysteine trước phẫu thuật trong phẫu thuật tim và không phải tim có liên quan đến việc giảm tỷ lệ mắc POAF, [831–834] nhưng không phải là các biến cố bất lợi lớn. [835] Một đánh giá tổng quan về 89 RCT từ 23 phân tích tổng hợp (19.211 bệnh nhân, nhưng không nhất thiết là AF) cho thấy thuốc chẹn beta không có lợi ích trong phẫu thuật tim đối với tử vong, MI hoặc đột quỵ. Trong phẫu thuật không phải tim, thuốc chẹn beta có liên quan đến việc giảm tỷ lệ MI sau phẫu thuật (phạm vi RR, 0,08–0,92), nhưng tỷ lệ tử vong cao hơn (phạm vi RR, 1,03–1,31) và tăng nguy cơ đột quỵ (phạm vi RR, 1,33–7,72). [836] Phòng ngừa AF quanh phẫu thuật cũng có thể đạt được bằng amiodarone. Trong phân tích tổng hợp, amiodarone (uống hoặc tiêm tĩnh mạch [i.v.]) và thuốc chẹn beta có hiệu quả như nhau trong việc giảm AF sau phẫu thuật, [837] nhưng sự kết hợp của chúng tốt hơn thuốc chẹn beta đơn độc. [838] Liều tích lũy amiodarone thấp hơn (<3000 mg trong giai đoạn nạp) có thể có hiệu quả, với ít tác dụng phụ hơn. [837,839,840] Nên tránh ngừng thuốc chẹn beta do tăng nguy cơ POAF. [841] Các chiến lược điều trị khác (steroid, magiê, sotalol, tạo nhịp (hai) nhĩ và tiêm botulium vào lớp mỡ ngoài màng ngoài tim) thiếu bằng chứng khoa học về việc ngăn ngừa AF quanh phẫu thuật. [842,843] Mổ màng ngoài tim sau phẫu thuật, do giảm tràn dịch màng ngoài tim sau phẫu thuật, cho thấy giảm đáng kể POAF ở những bệnh nhân trải qua phẫu thuật tim (OR, 0,44; 95% CI, 0,27–0,70; P = 0,0005). [844–846] Ở 3209 bệnh nhân trải qua phẫu thuật ngực không phải tim, colchicine không dẫn đến bất kỳ giảm đáng kể nào về AF so với giả dược (HR, 0,85; 95% CI, 0,65–1,10; P = 0,22). [847]

Bằng chứng về việc phòng ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ ở POAF bằng OAC còn hạn chế. [822,827] Liệu pháp chống đông đường uống có liên quan đến nguy cơ chảy máu cao ngay sau phẫu thuật tim hoặc các can thiệp lớn không liên quan đến tim. [827] Ngược lại, các phân tích tổng hợp của các nghiên cứu theo dõi quan sát cho thấy tác động bảo vệ có thể có của OAC ở POAF đối với tỷ lệ tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân [848] và nguy cơ thấp hơn về các biến cố huyết khối tắc mạch sau phẫu thuật tim, kèm theo tỷ lệ chảy máu cao hơn. [849] Lực lượng đặc nhiệm này khuyến cao điều trị AF sau phẫu thuật theo con đường AF-CARE như đã thảo luận đối với AF do tác nhân kích hoạt (với con đường [R] giống như đối với AF được chẩn đoán lần đầu). Các RCT đang diễn ra trong phẫu thuật tim (NCT04045665) và phẫu thuật không liên quan đến tim (NCT03968393) sẽ cung cấp thông tin về việc sử dụng OAC dài hạn tối ưu ở những bệnh nhân POAF. Trong khi chờ đợi kết quả của các thử nghiệm này, lực lượng đặc nhiệm này khuyến cáo sau khi nguy cơ chảy máu cấp tính đã ổn định, nên cân nhắc sử dụng OAC dài hạn ở những bệnh nhân mắc POAF theo các yếu tố nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch của họ.

Bảng khuyến cáo 26 — Khuyến cáo cho việc quản lý AF sau phẫu thuật (xem thêm Bằng chứng Bảng 26)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Khuyến cáo chung cho bệnh nhân AF và chỉ định dùng liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu đồng thời | ||

| Liệu pháp amiodarone quanh phẫu thuật được khuyến cáo khi cần điều trị bằng thuốc để ngăn ngừa AF sau phẫu thuật tim. [838,839,850,851] |

I |

A |

| Phẫu thuật lấy bỏ màng ngoài tim đồng thời được xem xét ở các bệnh nhân trải qua phẫu thuật tim để ngăn ngừa AF sau phẫu thuật. [845,846] |

IIa |

B |

| Kháng đông uống dài hạn nên được xét xét ở các bệnh nhân với AF sau phẫu thuật sau phẫu thuật tim và ngoài tim khi nguy cơ thuyên tắc huyết khối tăng lên, để phòng ngừa đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối thuyên tắc. [811,852–854] |

IIa |

B |

| Không khuyến cáo sử dụng thuốc chẹn beta thường quy ở những bệnh nhân phẫu thuật không phải tim để ngăn ngừa AF sau phẫu thuật. [836,855] |

III |

B |

AF, rung nhĩ.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng

9.7. AF-CARE trong đột quỵ do tắc mạch nguồn gốc không xác định

Thuật ngữ ‘đột quỵ do tắc mạch không xác định nguồn gốc’ (embolic stroke of undetermined source’: ESUS) được đưa ra để xác định các cơn đột quỵ không phải do tắc mạch mà cơ chế có khả năng là tắc mạch, nhưng nguồn gốc vẫn chưa được xác định. [856] Lưu ý, những bệnh nhân này có nguy cơ đột quỵ tái phát là 4%–5% mỗi năm. [856] Các nguồn tắc mạch chính liên quan đến ESUS là AF ẩn (concealed), bệnh cơ tim nhĩ, bệnh thất trái, mảng xơ vữa động mạch, lỗ thông bầu dục (PFO), bệnh van tim và ung thư. Bệnh cơ tim nhĩ và bệnh thất trái là những nguyên nhân phổ biến nhất. [856] AF được báo cáo là cơ chế cơ bản ở 30% bệnh nhân ESUS. [857–859] Việc phát hiện AF ở bệnh nhân ESUS tăng lên khi theo dõi tim lâu hơn (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S29). [857,860–864] Điều này cũng đúng trong suốt thời gian theo dõi tim cấy, với khả năng phát hiện AF dao động từ 2% trong 1 tuần đến hơn 20% trong 3 năm. [865] Ở những bệnh nhân mắc ESUS, các yếu tố liên quan đến việc phát hiện AF tăng lên là tuổi tác tăng lên, [866,867] phì đại nhĩ trái, [866] vị trí vỏ não của đột quỵ, [868] bệnh mạch máu lớn hoặc nhỏ, [863] số các nhắt bóp nhĩ sớm tăng lên trong 24 giờ, [868] nhịp tim không đều, [859] và điểm phân tầng nguy cơ (như CHA2DS2-VA, [869] Brown ESUS-AF, [870] HAVOC, [871] và C2HEST872). Lực lượng đặc nhiệm này khuyến cáo theo dõi kéo dài tùy thuộc vào sự hiện diện của các dấu hiệu nguy cơ đã đề cập ở trên. [865,873,874]

Bằng chứng hiện có, gồm hai RCT đã hoàn thành và một RCT đã dừng lại vì vô ích, không ủng hộ việc sử dụng DOAC so với aspirin ở những bệnh nhân mắc ESUS cấp tính không có AF được ghi nhận. [875–877] Các thử nghiệm đang diễn ra sẽ cung cấp hướng dẫn thêm (NCT05134454, NCT05293080, NCT04371055)

Bảng khuyến cáo 27 — Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ do tắc mạch không rõ nguồn gốc (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 27)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Khuyến cáo theo dõi AF kéo dài ở những bệnh nhân mắc ESUS để đưa ra quyết định điều trị AF. [861–863] |

I |

B |

| Không khuyến cáo bắt đầu dùng thuốc chống đông đường uống ở những bệnh nhân mắc ESUS không có bằng chứng AF do thiếu hiệu quả trong việc ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối tắc mạch. [875,876] |

III |

A |

AF: rung nhĩ; ESUS (embolic stroke of undetermined source): đột quỵ do tắc mạch không xác định được nguồn gốc.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

9.8. AF-CARE trong quá trình thai nghén

Rung nhĩ là một trong những loạn nhịp tim phổ biến nhất trong thai kỳ, với tỷ lệ mắc bệnh ngày càng tăng do tuổi sản phụ cao hơn và thay đổi lối sống, và vì nhiều phụ nữ mắc bệnh tim bẩm sinh sống sót đến tuổi sinh sản. [878–881] Dẫn truyền nhĩ thất nhanh trong AF có thể gây ra hậu quả huyết động nghiêm trọng cho mẹ và thai nhi. AF trong thai kỳ có liên quan đến nguy cơ tử vong tăng cao. [882] Một phương pháp tiếp cận đa ngành là điều cần thiết để ngăn ngừa các biến chứng cho mẹ và thai nhi, tập hợp các bác sĩ phụ khoa, bác sĩ sơ sinh, bác sĩ gây mê và bác sĩ tim mạch có kinh nghiệm trong y học sản khoa. [883]

Thai kỳ có liên quan đến tình trạng tăng đông máu và tăng nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch. [884] Các quy tắc đánh giá nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch tương tự nên được sử dụng như ở phụ nữ không mang thai, như được nêu chi tiết trong Hướng dẫn ESC năm 2018 về việc quản lý các bệnh tim mạch trong thai kỳ. [885]

Các thuốc được ưa chuộng để chống đông máu trong AF trong quá trình thai kỳ là heparin không phân đoạn hoặc heparin trọng lượng phân tử thấp (LMWH), không qua nhau thai. Thuốc đối kháng vitamin K nên tránh trong tam cá nguyệt đầu tiên (nguy cơ sảy thai, quái thai) và từ tuần thứ 36 trở đi (nguy cơ chảy máu nội sọ ở thai nhi nếu sinh non sớm). Thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp không được khuyến cáo trong thai kỳ do lo ngại về tính an toàn. [886] Tuy nhiên, việc phơi nhiễm ngẫu nhiên trong thai kỳ không nên dẫn đến khuyến cáo chấm dứt thai kỳ. [887] Nên sinh thường đối với hầu hết phụ nữ, nhưng chống chỉ định trong quá trình điều trị VKA vì nguy cơ chảy máu nội sọ ở thai nhi. [885] Thuốc chẹn thụ thể beta-1 chọn lọc tiêm tĩnh mạch được khuyến cáo là lựa chọn đầu tiên để kiểm soát tần số tim cấp thời trong AF. [888] Điều này không bao gồm atenolol, có thể dẫn đến chậm phát triển trong tử cung. [889] Nếu thuốc chẹn beta không hiệu quả, có thể cân nhắc digoxin và verapamil để kiểm soát tần số tim (nên tránh dùng verapamil trong tam cá nguyệt đầu tiên). Kiểm soát nhịp tim là chiến lược được ưu tiên trong thời kỳ mang thai. Nên thực hiện sốc điện nếu có tình trạng huyết động không ổn định, nguy cơ đáng kể cho mẹ hoặc thai nhi hoặc có HCM đi kèm. Có thể thực hiện sốc điện an toàn mà không ảnh hưởng đến lưu lượng máu của thai nhi và nguy cơ loạn nhịp tim thai nhi hoặc chuyển dạ sớm là thấp. Cần theo dõi chặt chẽ nhịp tim của thai nhi trong suốt và sau khi sốc điện, thường nên dùng thuốc chống đông trước. [885] Ở những phụ nữ ổn định về huyết động không có bệnh tim cấu trúc, có thể cân nhắc dùng ibutilide hoặc flecainide tiêm tĩnh mạch để chấm dứt AF, nhưng kinh nghiệm còn hạn chế. [890] Thông thường, nên tránh triệt phá qua catheter trong thời kỳ mang thai, [883] nhưng về mặt kỹ thuật có thể thực hiện mà không cần bức xạ trong các trường hợp có triệu chứng kháng trị với phương pháp tiếp cận huỳnh quang tối thiểu/không cần. [883]

Tư vấn là quan trọng đối với phụ nữ có khả năng sinh con trước khi mang thai, nêu có những nguy cơ tiềm ẩn của thuốc chống đông máu và thuốc kiểm soát nhịp tim hoặc tần số (bao gồm cả nguy cơ gây quái thai, nếu có). Nên chủ động thảo luận về biện pháp tránh thai và chuyển sang thuốc an toàn kịp thời.

Bảng khuyến cáo 28 — Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân bị AF trong thời kỳ mang thai (xem thêm Bằng chứng Bảng 28)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Chuyển nhịp bằng điện ngay lập tức được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân bị AF trong thời kỳ mang thai và tình trạng huyết động không ổn định hoặc AF do kích thích sớm để cải thiện kết quả cho mẹ và thai nhi. [885,891–893] |

I |

C |

| Điều trị chống đông bằng LMWH hoặc VKA (trừ VKA trong tam cá nguyệt đầu tiên hoặc sau Tuần 36) được khuyến cáo cho những bệnh nhân mang thai bị AF có nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch cao để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối tắc mạch. [885] |

I |

C |

| Thuốc chẹn chọn lọc beta-1 được khuyến cáo để kiểm soát nhịp tim trong AF trong thời kỳ mang thai nhằm giảm các triệu chứng và cải thiện kết quả cho mẹ và thai nhi, ngoại trừ atenolol. [888] |

I |

C |

| Cần cân nhắc chuyển nhịp bằng điện cho AF dai dẳng ở phụ nữ mang thai bị HCM để cải thiện kết quả cho mẹ và thai nhi. [885,894] |

I |

C |

| Cần cân nhắc dùng digoxin để kiểm soát tần số tim trong AF trong thời kỳ mang thai, nếu thuốc chẹn beta không hiệu quả hoặc không dung nạp, để giảm các triệu chứng và cải thiện kết quả cho mẹ và thai nhi. [885] |

IIa |

C |

| Ibutilide hoặc flecainide tiêm tĩnh mạch có thể được cân nhắc để chấm dứt AF ở những bệnh nhân mang thai ổn định có tim bình thường về mặt cấu trúc để cải thiện kết quả cho mẹ và thai nhi.[895,896] |

IIa |

C |

| Flecainide hoặc propafenone có thể được cân nhắc để kiểm soát nhịp tim lâu dài trong thai kỳ, nếu thuốc kiểm soát tần số tim không hiệu quả hoặc không dung nạp, để giảm triệu chứng và cải thiện kết quả cho mẹ và thai nhi.[885] |

IIb |

C |

AF: rung nhĩ; HCM: bệnh cơ tim phì đại; LMWH: heparin trọng lượng phân tử thấp; VKA: thuốc đối kháng vitamin K.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

9.9. AF-CARE trong bệnh tim bẩm sinh

Tỷ lệ sống sót của bệnh nhân mắc bệnh tim bẩm sinh đã tăng theo thời gian, nhưng dữ liệu đáng tin cậy về việc quản lý AF vẫn còn thiếu và bằng chứng có sẵn chủ yếu có được từ các nghiên cứu quan sát. Thuốc chống đông đường uống được khuyến cáo cho tất cả bệnh nhân AF và có sử chữa trong tim, bệnh tim bẩm sinh tím tái, giảm nhẹ Fontan hoặc tâm thất phải hệ thống bất kể các yếu tố nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch của cá nhân. [897] Bệnh nhân AF và các bệnh tim bẩm sinh khác nên tuân theo phân tầng nguy cơ chung để sử dụng OAC trong AF (tức là tùy thuộc vào nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch hoặc điểm CHA2DS2-VA). Thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp chống chỉ định ở những bệnh nhân có van tim cơ học, [331] nhưng có vẻ an toàn ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh tim bẩm sinh, [898,899] hoặc những bệnh nhân có van tim sinh học. [900,901]

Có thể sử dụng thận trọng các thuốc kiểm soát tần số như thuốc chẹn thụ thể beta-1 chọn lọc, verapamil, diltiazem và digoxin, đồng thời theo dõi nhịp tim chậm và hạ huyết áp. Các chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp như amiodarone có thể hiệu quả, nhưng cần theo dõi nhịp chậm. Khi lên kế hoạch chuyển nhịp, nên cân nhắc cả OAC và TOE trong 3 tuần vì huyết khối thường gặp ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh tim bẩm sinh và loạn nhịp nhĩ. [902,903] Các phương pháp triệt phá có thể thành công ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh tim bẩm sinh, nhưng tỷ lệ tái phát AF có thể cao (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S30).

Ở những bệnh nhân bị khiếm khuyết vách liên nhĩ, có thể thực hiện đóng trước thập kỷ thứ tư của cuộc đời để giảm nguy cơ AF hoặc AFL. [904] Những bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ đã đóng PFO có thể có nguy cơ AF cao hơn, [905] nhưng ở những bệnh nhân bị PFO và AF, không khuyến cáo đóng PFO để phòng ngừa đột quỵ. Phẫu thuật AF hoặc triệt phá qua catheter có thể được cân nhắc tại thời điểm đóng lỗ thông vách liên nhĩ trong một nhóm đa chuyên khoa. [906–908] Việc triệt phá AF qua catheter đối với chứng loạn nhịp nhĩ muộn có khả năng có hiệu quả sau khi đóng vách liên nhĩ bằng phẫu thuật.[909]

Bảng khuyến cáo 29 — Khuyến cáo cho bệnh nhân bị AF và bệnh tim bẩm sinh (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 29)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Nên cân nhắc dùng thuốc chống đông đường uống cho tất cả bệnh nhân mắc bệnh tim bẩm sinh ở người lớn có AF/AFL và sửa chữa trong tim, tím tái, giảm nhẹ Fontan hoặc tâm thất phải hệ thống để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối tắc mạch, bất kể các yếu tố nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch khác. [897] |

IIa |

C |

AF: rung nhĩ; AFL: cuồng nhĩ.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng

9.10. AF-CARE trong các rối loạn nội tiết

Rối loạn chức năng nội tiết có liên quan chặt chẽ đến AF, vừa là tác động trực tiếp của hormone nội tiết vừa là hậu quả của các phương pháp điều trị bệnh nội tiết. Do đó, việc quản lý tối ưu các rối loạn nội tiết là một phần của con đường AF-CARE.[910,911]

Cường giáp lâm sàng và cận lâm sàng, cũng như suy giáp cận lâm sàng, có liên quan đến nguy cơ AF tăng cao. [912,913] Bệnh nhân có biểu hiện AF mới khởi phát hoặc tái phát nên được xét nghiệm nồng độ hormone kích thích tuyến giáp (TSH). Nguy cơ AF tăng cao ở những bệnh nhân dễ bị tổn thương, bao gồm người cao tuổi và những người mắc bệnh tâm nhĩ cấu trúc, [914,915] cũng như bệnh nhân ung thư đang dùng thuốc ức chế điểm kiểm soát miễn dịch. [916,917] Ở bệnh cường giáp, và thậm chí ở phạm vi bình giáp, nguy cơ AF tăng theo mức giảm TSH và mức tăng cao của thyroxine. [918,919] Hơn nữa, nguy cơ đột quỵ cao hơn ở những bệnh nhân cường giáp, có thể giảm nhẹ bằng cách điều trị rối loạn tuyến giáp. [920,921] Amiodarone gây rối loạn chức năng tuyến giáp ở 15%–20% bệnh nhân được điều trị, dẫn đến cả suy giáp và cường giáp, [922,923] cần chuyển đến bác sĩ nội tiết (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến để biết thêm chi tiết)

Tăng canxi máu cũng có thể gây loạn nhịp tim, nhưng vai trò của cường cận giáp nguyên phát trong AF mới phát hiện chưa được nghiên cứu đầy đủ. Phẫu thuật cắt tuyến cận giáp đã được phát hiện là làm giảm cả các nhắt bóp sớm trên thất và thất. [924–926] Cường aldosteron nguyên phát có liên quan đến việc tăng nguy cơ AF thông qua các tác động trực tiếp và tác động mạch máu, [927,928] với tỷ lệ AF mới phát cao gấp ba lần so với bệnh nhân tăng huyết áp nguyên phát.[929] Tăng cortisol huyết tương được dự đoán về mặt di truyền có liên quan đến nguy cơ AF cao hơn và bệnh nhân bị u tuyến thượng thận ngẫu nhiên có tiết cortisol dưới lâm sàng có tỷ lệ AF cao hơn. [930,931] Bệnh to đầu chi có thể làm tăng chất nền cho AF, với tỷ lệ AF mới mắc cao hơn đáng kể so với nhóm đối chứng trong quá trình theo dõi dài hạn, ngay cả sau khi điều chỉnh các yếu tố nguy cơ AF.[932]

Mối liên quan giữa bệnh tiểu đường type 2 và AF được thảo luận trong Mục 5.3 (tái phát AF) và Mục 10.5 (AF mới mắc). Ngoài các cơ chế kháng insulin điển hình của bệnh tiểu đường type 2, tình trạng mất tín hiệu insulin gần đây có liên quan đến những thay đổi về điện có thể dẫn đến AF. Bệnh tiểu đường type 1 có liên quan đến việc tăng nguy cơ mắc một số bệnh tim mạch bao gồm AF. [933–937]

9.11. AF-CARE trong bệnh cơ tim di truyền và hội chứng loạn nhịp tim nguyên phát

Tỷ lệ mắc và tỷ lệ lưu hành AF cao hơn đã được mô tả ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh cơ tim di truyền và hội chứng loạn nhịp tim nguyên phát. [271,938–970] AF có thể là đặc điểm biểu hiện hoặc là đặc điểm lâm sàng duy nhất. [969,971–975] AF ở những bệnh nhân này có liên quan đến các kết quả lâm sàng bất lợi, [947, 954, 959, 963, 965, 976–978] và có ý nghĩa quan trọng đối với việc quản lý (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S31). Khi AF xuất hiện ở độ tuổi trẻ, cần phải thẩm vấn cẩn thận về tiền sử gia đình và tìm kiếm bệnh lý tiềm ẩn. [979]

Các phương pháp kiểm soát nhịp tim có thể là thách thức ở những bệnh nhân mắc bệnh cơ tim di truyền và hội chứng loạn nhịp tim nguyên phát. Ví dụ, nhiều loại thuốc có nguy cơ gây ra các tác dụng phụ cao hơn hoặc có thể chống chỉ định (ví dụ: amiodarone và sotalol trong hội chứng QT dài bẩm sinh và AAD loại IC trong hội chứng Brugada) (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng S6).

Do những tác dụng phụ lâu dài, việc sử dụng amiodarone trong thời gian dài là vấn đề đối với những cá nhân thường trẻ tuổi này. Ở những bệnh nhân có cấy máy khử rung tim, AF là nguyên nhân phổ biến gây ra các cú sốc không phù hợp. [959,966,980,981] Việc lập trình một vùng rung thất có tần số cao duy nhất ≥210–220 nhịp/phút với thời gian phát hiện dài là an toàn, [950,953,982] và được đề xuất ở những bệnh nhân không có tiền sử nhịp nhanh thất đơn hình chậm. Có thể cân nhắc cấy dây dẫn nhĩ trong trường hợp nhịp tim chậm đáng kể khi điều trị bằng thuốc chẹn beta.

Những bệnh nhân mắc hội chứng Wolff–Parkinson–White và AF có nguy cơ nhịp thất nhanh do dẫn truyền nhanh hoạt động điện nhĩ đến thất qua đường dẫn truyền phụ, có khả năng dẫn đến rung thất và tử vong đột ngột. [983,984] Cần phải chuyển nhịp bằng điện ngay lập tức cho những bệnh nhân bị tổn thương huyết động với AF tiền kích thích và nên tránh dùng thuốc điều biến nút nhĩ thất. [985,986] Có thể thử chuyển nhịp dược lý bằng cách sử dụng ibutilide [987] hoặc flecainide, trong khi nên thận trọng khi sử dụng propafenone do tác dụng lên nút nhĩ thất. [988,989] Nên tránh dùng amiodarone trong AF kích thích trước do tác dụng chậm của thuốc này. Có thể tìm thấy thêm thông tin chi tiết về bệnh cơ tim di truyền trong Hướng dẫn ESC năm 2023 về việc quản lý bệnh cơ tim.[990]

9.12. AF-CARE trong ung thư

Tất cả các loại ung thư đều có nguy cơ mắc AF tăng lên, với tỷ lệ mắc dao động từ 2% đến 28%. [991–995] Sự xuất hiện của AF thường có thể liên quan đến nền nhĩ có từ trước với nguy cơ mắc AF. AF có thể là dấu hiệu của ung thư tiềm ẩn, nhưng cũng có thể xuất hiện trong bối cảnh phẫu thuật, hóa trị hoặc xạ trị đồng thời. [916, 994, 996] Nguy cơ mắc AF phụ thuộc vào, trong số các yếu tố khác, loại ung thư và giai đoạn ung thư, [997] và cao hơn ở những bệnh nhân lớn tuổi mắc bệnh tim mạch từ trước. [991,993,994] Một số thủ thuật có liên quan đến tỷ lệ mắc AF cao hơn, gồm phẫu thuật phổi (từ 6% đến 32%) và phẫu thuật không phải ngực như cắt đại tràng (4%–5%). [994]

Rung nhĩ trong bối cảnh ung thư có liên quan đến nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch toàn thân và đột quỵ cao gấp đôi, và nguy cơ suy tim tăng gấp sáu lần. [991,994] Mặt khác, sự đồng tồn tại của ung thư làm tăng nguy cơ tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân và chảy máu lớn ở những bệnh nhân bị AF. [998] Chảy máu ở những người dùng OAC cũng có thể làm lộ sự hiện diện của ung thư.[999]

Điểm nguy cơ đột quỵ có thể đánh giá thấp nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch ở những bệnh nhân ung thư. [1000] Mối liên quan giữa ung thư, AF và đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ cũng khác nhau giữa các loại ung thư. Ở một số loại ung thư, nguy cơ chảy máu dường như vượt quá nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch. [998] Do đó, phân tầng nguy cơ rất phức tạp trong nhóm dân số này và nên được thực hiện trên cơ sở cá thể khi xem xét loại ung thư, giai đoạn, tiên lượng, nguy cơ chảy máu và các yếu tố nguy cơ khác. Những khía cạnh này có thể thay đổi trong một thời gian ngắn, đòi hỏi phải đánh giá và quản lý động học.

Tương tự như bệnh nhân không phải ung thư, DOAC ở những người bị ung thư có hiệu quả tương tự và an toàn hơn so với VKA. [1001–1010] Heparin trọng lượng phân tử thấp là một lựa chọn chống đông máu ngắn hạn, chủ yếu trong một số phương pháp điều trị ung thư, chảy máu hoạt động gần đây hoặc giảm tiểu cầu. [1011] Quyết định về quản lý AF, gồm kiểm soát nhịp, được thực hiện tốt nhất trong một nhóm đa ngành tim mạch ung thư. [916,1012] Cần chú ý đến các tương tác với các phương pháp điều trị ung thư, đặc biệt là kéo dài khoảng QT với AAD.

9.13. AF-CARE ở bệnh nhân lớn tuổi, mắc nhiều bệnh hoặc suy yếu

Rung nhĩ tăng theo tuổi và bệnh nhân lớn tuổi thường mắc nhiều bệnh và suy yếu, liên quan đến kết quả lâm sàng tệ hơn.[1013–1016] Suy yếu là tình trạng cùng tồn tại hai hoặc nhiều bệnh được chẩn đoán y khoa ở cùng một cá nhân. Suy yếu được định nghĩa là một người dễ bị tổn thương hơn và ít có khả năng phản ứng với tác nhân gây căng thẳng hoặc sự kiện cấp tính, làm tăng nguy cơ gặp phải kết quả bất lợi.[1016,1017] Tỷ lệ suy yếu trong AF thay đổi do các phương pháp đánh giá khác nhau, từ 4,4% đến 75,4% và tỷ lệ mắc AF ở nhóm người suy yếu dao động từ 48,2% đến 75,4%. [1018] Tình trạng suy yếu là một yếu tố nguy cơ độc lập mạnh đối với AF mới khởi phát ở người lớn tuổi bị tăng huyết áp. [1019] Rung nhĩ ở bệnh nhân suy yếu có liên quan đến việc sử dụng OAC ít hơn và tỷ lệ quản lý bằng chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp thấp hơn. [1015,1018,1020] Việc bắt đầu dùng thuốc chống đông đường uống ở những bệnh nhân AF mắc nhiều bệnh lý lớn tuổi, suy yếu đã được cải thiện kể từ khi DOAC ra đời, nhưng vẫn thấp hơn ở những bệnh nhân AF ở độ tuổi lớn hơn (OR, 0,98 mỗi năm; 95% CI, 0,98–0,98), mắc chứng mất trí (OR, 0,57; 95% CI, 0,55–0,58) hoặc yếu (OR, 0,74; 95% CI, 0,72–0,76). [1021] Giá trị của dữ liệu quan sát cho thấy lợi ích tiềm năng từ OAC (đặc biệt là DOAC) bị hạn chế do sai lệch kê đơn. [1022–1027] Những bệnh nhân suy yếu từ ≥75 tuổi dùng nhiều loại thuốc và ổn định khi dùng VKA có thể vẫn dùng VKA thay vì chuyển sang DOAC (Mục 6.2). [309]

9.14. AF-CARE trong cuồng nhĩ

Do mối liên quan giữa AFL và kết quả huyết khối tắc mạch, và sự phát triển thường xuyên của AF ở những bệnh nhân mắc AFL, việc quản lý các bệnh đi kèm và các yếu tố nguy cơ trong AFL điều trị như AF (xem Mục 5). Tương tự như vậy, cách tiếp cận để ngăn ngừa huyết khối tắc mạch trong AFL gồm OAC quanh thủ thuật và dài hạn (xem Mục 6). Kiểm soát tần số có thể khó đạt được trong AFL, mặc dù có liệu pháp kết hợp. Kiểm soát nhịp thường là phương pháp tiếp cận đầu tiên, [983] với các thử nghiệm ngẫu nhiên nhỏ cho thấy triệt phá tĩnh mạch chủ-ba lá (CTI) vượt trội hơn AAD. [1028,1029] AFL tái phát không phổ biến sau khi đạt được và xác nhận block hai chiều trong AFL phụ thuộc CTI điển hình. Tuy nhiên, phần lớn bệnh nhân (50%–70%) đã biểu hiện AF trong quá trình theo dõi dài hạn trong các nghiên cứu quan sát sau khi triệt phá AFL. [1030,1031] Do đó, cần phải đánh giá lại động lực dài hạn ở tất cả bệnh nhân bị AFL theo phương pháp AF-CARE. Chi tiết hơn về việc quản lý AFL và các loạn nhịp nhĩ khác được mô tả trong Hướng dẫn ESC năm 2019 về việc quản lý bệnh nhân bị nhịp nhanh trên thất. [983]

Bảng khuyến cáo 30 — Khuyến cáo để phòng ngừa huyết khối tắc mạch ở rung nhĩ (xem cũng Bảng bằng chứng 30)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Thuốc chống đông đường uống được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân cuồng nhĩ có nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch cao để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối tắc mạch. [86,1032] |

I |

B |

AF: rung nhĩ; AFL: cuồng nhĩ.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng

(Còn nữa)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO

- Pokorney SD, Cocoros N, Al-Khalidi HR, Haynes K, Li S, Al-Khatib SM, et al. Effect of mailing educational material to patients with atrial fibrillation and their clinicians on use

of oral anticoagulants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2214321. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14321

714. Ritchie LA, Penson PE, Akpan A, Lip GYH, Lane DA. Integrated care for atrial fibrillation management: the role of the pharmacist. Am J Med 2022;135:1410–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.07.014 - Guo Y, Guo J, Shi X, Yao Y, Sun Y, Xia Y, et al. Mobile health technology-supported atrial fibrillation screening and integrated care: a report from the mAFA-II trial longterm extension cohort. Eur J Intern Med 2020;82:105–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.09.024

- Yan H, Du YX, Wu FQ, Lu XY, Chen RM, Zhang Y. Effects of nurse-led multidisciplinary team management on cardiovascular hospitalization and quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2022;127:104159. https:// doi.org/10.1016/ j.ijnurstu. 2021. 104159

- Stewart S, Ball J, Horowitz JD, Marwick TH, Mahadevan G, Wong C, et al. Standard

versus atrial fibrillation-specific management strategy (SAFETY) to reduce recurrent

admission and prolong survival: pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial.

Lancet 2015;385:775–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61992-9 - Cox JL, Parkash R, Foster GA, Xie F, MacKillop JH, Ciaccia A, et al. Integrated management program advancing community treatment of atrial fibrillation (IMPACT-AF): a

cluster randomized trial of a computerized clinical decision support tool. Am Heart J 2020;224:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2020.02.019

\719. Sposato LA, Stirling D, Saposnik G. Therapeutic decisions in atrial fibrillation for stroke

prevention: the role of aversion to ambiguity and physicians’ risk preferences. J Stroke

Cerebrovasc Dis 2018;27:2088–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis. 2018.03.005

720. Noseworthy PA, Brito JP, Kunneman M, Hargraves IG, Zeballos-Palacios C, Montori

VM, et al. Shared decision-making in atrial fibrillation: navigating complex issues in partnership with the patient. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2019;56:159–63. https://doi.org/10.

1007/s10840-018-0465-5

721. Poorcheraghi H, Negarandeh R, Pashaeypoor S, Jorian J. Effect of using a mobile drug

management application on medication adherence and hospital readmission among

elderly patients with polypharmacy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv

Res 2023;23:1192. https: // doi.org/ 10.1186/ s12913 -023 – 10177-4

- Kotecha D, Chua WWL, Fabritz L, Hendriks J, Casadei B, Schotten U, et al. European

Society of Cardiology (ESC) Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Taskforce, the CATCH ME

consortium, and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). European

Society of Cardiology smartphone and tablet applications for patients with atrial fibrillation and their health care providers. Europace 2018;20:225–33. https://doi.org/10.

1093/europace/eux299

723. Bunting KV, Gill SK, Sitch A, Mehta S, O’Connor K, Lip GY, et al. Improving the diagnosis of heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart 2021;107:902–8. https://

doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-318557

724. Donal E, Lip GY, Galderisi M, Goette A, Shah D, Marwan M, et al. EACVI/EHRA expert

consensus document on the role of multi-modality imaging for the evaluation of patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;17:355–83. https:// doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev354 - Bunting KV, O’Connor K, Steeds RP, Kotecha D. Cardiac imaging to assess left ventricular systolic function in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2021;139:40–9. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.10.012

726. Timperley J, Mitchell AR, Becher H. Contrast echocardiography for left ventricular

opacification. Heart 2003;89:1394–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/heart.89.12.1394 - Kotecha D, Mohamed M, Shantsila E, Popescu BA, Steeds RP. Is echocardiography valid

and reproducible in patients with atrial fibrillation? A systematic review. Europace 2017;

19:1427–38. https: // doi.org/10.1093/ europace/eux027 - Quintana RA, Dong T, Vajapey R, Reyaldeen R, Kwon DH, Harb S, et al. Preprocedural

multimodality imaging in atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2022;15:e014386.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.122.014386

729. Laubrock K, von Loesch T, Steinmetz M, Lotz J, Frahm J, Uecker M, et al. Imaging of arrhythmia: real-time cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in atrial fibrillation. Eur J Radiol Open 2022;9:100404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejro.2022.100404 - Sciagrà R, Sotgia B, Boni N, Pupi A. Assessment of the influence of atrial fibrillation on

gated SPECT perfusion data by comparison with simultaneously acquired nongated SPECT data. J Nucl Med 2008;49:1283–7. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.108.051797 - Clayton B, Roobottom C, Morgan-Hughes G. CT coronary angiography in atrial fibrillation: a comparison of radiation dose and diagnostic confidence with retrospective

gating vs prospective gating with systolic acquisition. Br J Radiol 2015;88:20150533.

https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20150533

732. Thrall G, Lane D, Carroll D, Lip GY. Quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: a

systematic review. Am J Med 2006;119:448.e1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.

2005.10.057

733. Steinberg BA, Dorian P, Anstrom KJ, Hess R, Mark DB, Noseworthy PA, et al.

Patient-reported outcomes in atrial fibrillation research: results of a Clinicaltrials.gov

analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:599–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2019.

03.008

734. Potpara TS, Mihajlovic M, Zec N, Marinkovic M, Kovacevic V, Simic J, et al.

Self-reported treatment burden in patients with atrial fibrillation: quantification, major

determinants, and implications for integrated holistic management of the arrhythmia.

Europace 2020;22:1788–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa210 - Moons P, Norekvål TM, Arbelo E, Borregaard B, Casadei B, Cosyns B, et al. Placing

patient-reported outcomes at the centre of cardiovascular clinical practice: implications for quality of care and management. Eur Heart J 2023;44:3405–22. https://doi.

org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad514

736. Allan KS, Aves T, Henry S, Banfield L, Victor JC, Dorian P, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with catheter ablation or antiarrhythmic

drug therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CJC Open 2020;2:286–95.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2020.03.013

737. Vanderhout S, Fergusson DA, Cook JA, Taljaard M. Patient-reported outcomes and

target effect sizes in pragmatic randomized trials in ClinicalTrials.gov: a cross-sectional

analysis. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003896 - Steinberg BA, Piccini JP, Sr. Tackling patient-reported outcomes in atrial fibrillation and

heart failure: identifying disease-specific symptoms? Cardiol Clin 2019;37:139–46.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2019.01.013

739. Härdén M, Nyström B, Bengtson A, Medin J, Frison L, Edvardsson N. Responsiveness

of AF6, a new, short, validated, atrial fibrillation-specific questionnaire—symptomatic

benefit of direct current cardioversion. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2010;28:185–91.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-010-9487-3

740. Tailachidis P, Tsimtsiou Z, Galanis P, Theodorou M, Kouvelas D, Athanasakis K. The

atrial fibrillation effect on QualiTy-of-Life (AFEQT) questionnaire: cultural adaptation

and validation of the Greek version. Hippokratia 2016;20:264–7. - Moreira RS, Bassolli L, Coutinho E, Ferrer P, Bragança ÉO, Carvalho AC, et al.

Reproducibility and reliability of the quality of life questionnaire in patients with atrial

fibrillation. Arq Bras Cardiol 2016;106:171–81. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20160026 - Arribas F, Ormaetxe JM, Peinado R, Perulero N, Ramírez P, Badia X. Validation of the

AF-QoL, a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire for patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2010;12:364–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eup421 - Braganca EO, Filho BL, Maria VH, Levy D, de Paola AA. Validating a new quality of life

questionnaire for atrial fibrillation patients. Int J Cardiol 2010;143:391–8. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.087

744. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. Atrial fibrillation data

collection reference guide Version 5.0.1. https://connect.ichom.org/wp-content/

uploads/2023/02/03-Atrial-Fibrillation-Reference-Guide-2023.5.0.1.pdf.

745. Dan GA, Dan AR, Ivanescu A, Buzea AC. Acute rate control in atrial fibrillation: an urgent need for the clinician. Eur Heart J Suppl 2022;24:D3–D10. https://doi.org/10.1093/

eurheartjsupp/suac022

746. Shima N, Miyamoto K, Kato S, Yoshida T, Uchino S; AFTER-ICU study group. Primary

success of electrical cardioversion for new-onset atrial fibrillation and its association

with clinical course in non-cardiac critically ill patients: sub-analysis of a multicenter observational study. J Intensive Care 2021;9:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-021-

00562-8

747. Betthauser KD, Gibson GA, Piche SL, Pope HE. Evaluation of amiodarone use for newonset atrial fibrillation in critically ill patients with septic shock. Hosp Pharm 2021;56:

116–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018578719868405 - Drikite L, Bedford JP, O’Bryan L, Petrinic T, Rajappan K, Doidge J, et al. Treatment

strategies for new onset atrial fibrillation in patients treated on an intensive care

unit: a systematic scoping review. Crit Care 2021;25:257. https://doi.org/10.1186/

s13054-021-03684-5

749. Bedford JP, Johnson A, Redfern O, Gerry S, Doidge J, Harrison D, et al. Comparative

effectiveness of common treatments for new-onset atrial fibrillation within the ICU:

accounting for physiological status. J Crit Care 2022;67:149–56. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.jcrc.2021.11.005

750. Iwahashi N, Takahashi H, Abe T, Okada K, Akiyama E, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Urgent control of rapid atrial fibrillation by landiolol in patients with acute decompensated heart

failure with severely reduced ejection fraction. Circ Rep 2019;1:422–30. https://doi.org/

10.1253/circrep.CR-19-0076

751. Unger M, Morelli A, Singer M, Radermacher P, Rehberg S, Trimmel H, et al. Landiolol in patients with septic shock resident in an intensive care unit (LANDI-SEP): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2018;19:637. https://doi.org/10.1186/

s13063-018-3024-6

752. Gonzalez-Pacheco H, Marquez MF, Arias-Mendoza A, Alvarez-Sangabriel A, Eid-Lidt

G, Gonzalez-Hermosillo A, et al. Clinical features and in-hospital mortality associated

with different types of atrial fibrillation in patients with acute coronary syndrome with

and without ST elevation. J Cardiol 2015;66:148–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.

11.001

753. Krijthe BP, Leening MJ, Heeringa J, Kors JA, Hofman A, Franco OH, et al. Unrecognized

myocardial infarction and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam Study. Int J Cardiol

2013;168:1453–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.057 - Soliman EZ, Safford MM, Muntner P, Khodneva Y, Dawood FZ, Zakai NA, et al. Atrial

fibrillation and the risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:107–14.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11912

755. Kralev S, Schneider K, Lang S, Suselbeck T, Borggrefe M. Incidence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing first-time coronary

angiography. PLoS One 2011;6:e24964. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024964 - Coscia T, Nestelberger T, Boeddinghaus J, Lopez-Ayala P, Koechlin L, Miró Ò, et al.

Characteristics and outcomes of type 2 myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:

427–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0043 - Guimaraes PO, Zakroysky P, Goyal A, Lopes RD, Kaltenbach LA, Wang TY. Usefulness

of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2019;123:12–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.09.031 - Erez A, Goldenberg I, Sabbag A, Nof E, Zahger D, Atar S, et al. Temporal trends and outcomes associated with atrial fibrillation observed during acute coronary syndrome: real-world data from the Acute Coronary Syndrome Israeli Survey (ACSIS), 2000– 2013. Clin Cardiol 2017;40:275–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22654

- Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas K, Rossell X, Adamo M, Ainslie J, et al. 2024 ESC

Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2024;

45:3415–537. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae177 - Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, et al. 2023 ESC

Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2023;44:

3720–826. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191 - Park DY, Wang P, An S, Grimshaw AA, Frampton J, Ohman EM, et al. Shortening the

duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention for

acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J 2022;

251:101–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2022.05.019 - Gargiulo G, Goette A, Tijssen J, Eckardt L, Lewalter T, Vranckx P, et al. Safety and efficacy outcomes of double vs. triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation following percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and

meta-analysis of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant-based randomized clinical

trials. Eur Heart J 2019;40:3757–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz732 - Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, Kelder JC, De Smet BJ, Herrman JP, et al. Use of

clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and

undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:1107–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12) 62177-1 - Lopes RD, Heizer G, Aronson R, Vora AN, Massaro T, Mehran R, et al. Antithrombotic

therapy after acute coronary syndrome or PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2019;

380:1509–24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1817083 - Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, Halperin J, Verheugt FW, Wildgoose P, et al.

Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N Engl J

Med 2016;375:2423–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1611594 - Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, Lip GYH, Ellis SG, Kimura T, et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2017;377:

1513–24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708454 - Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Eckardt L, Tijssen J, Lewalter T, Gargiulo G, et al.

Edoxaban-based versus vitamin K antagonist-based antithrombotic regimen after successful coronary stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation (ENTRUST-AF PCI): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2019;394:1335–43. https://doi.org/10.

1016/ S0140-6736 (19) 31872-0 - Lopes RD, Hong H, Harskamp RE, Bhatt DL, Mehran R, Cannon CP, et al. Safety and

efficacy of antithrombotic strategies in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:747–55. https:// doi.org/ 10.1001/ jamacardio.2019. 1880 - Oldgren J, Steg PG, Hohnloser SH, Lip GYH, Kimura T, Nordaby M, et al. Dabigatran

dual therapy with ticagrelor or clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention

in atrial fibrillation patients with or without acute coronary syndrome: a subgroup analysis from the RE-DUAL PCI trial. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1553–62. https://doi.org/10. 1093/eurheartj/ehz059

770. Potpara TS, Mujovic N, Proietti M, Dagres N, Hindricks G, Collet JP, et al. Revisiting the

effects of omitting aspirin in combined antithrombotic therapies for atrial fibrillation

and acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous coronary interventions: meta-analysis

of pooled data from the PIONEER AF-PCI, RE-DUAL PCI, and AUGUSTUS trials.

Europace 2020;22:33–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euz259 - Haller PM, Sulzgruber P, Kaufmann C, Geelhoed B, Tamargo J, Wassmann S, et al.

Bleeding and ischaemic outcomes in patients treated with dual or triple antithrombotic

therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother

2019;5:226–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvz021 - Lopes RD, Hong H, Harskamp RE, Bhatt DL, Mehran R, Cannon CP, et al. Optimal antithrombotic regimens for patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous

coronary intervention: an updated network meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5: 582–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.6175

773. Lopes RD, Vora AN, Liaw D, Granger CB, Darius H, Goodman SG, et al. An openlabel, 2 × 2 factorial, randomized controlled trial to evaluate the safety of apixaban vs. vitamin K antagonist and aspirin vs. placebo in patients with atrial fibrillation and

acute coronary syndrome and/or percutaneous coronary intervention: rationale and

design of the AUGUSTUS trial. Am Heart J 2018;200:17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ahj.2018.03.001

774. Windecker S, Lopes RD, Massaro T, Jones-Burton C, Granger CB, Aronson R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndrome treated medically or with percutaneous coronary intervention or undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the AUGUSTUS trial. Circulation 2019;140:1921–32. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119. 043308 - Harskamp RE, Fanaroff AC, Lopes RD, Wojdyla DM, Goodman SG, Thomas LE, et al.

Antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation after acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:417–27. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.035

776. Alexander JH, Wojdyla D, Vora AN, Thomas L, Granger CB, Goodman SG, et al. Risk/

benefit tradeoff of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation early and

late after an acute coronary syndrome or percutaneous coronary intervention: insights

from AUGUSTUS. Circulation 2020;141:1618–27. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULA

TIONAHA.120.046534

777. Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, Connolly SJ, Dyal L, Shestakovska O, et al. Safety

of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, multi-year, randomized trial of patients

receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology 2019;157:682–691.e2. https://doi.

org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056

778. Jeridi D, Pellat A, Ginestet C, Assaf A, Hallit R, Corre F, et al. The safety of long-term

proton pump inhibitor use on cardiovascular health: a meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2022;

11:4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11144096 - Scally B, Emberson JR, Spata E, Reith C, Davies K, Halls H, et al. Effects of gastroprotectant drugs for the prevention and treatment of peptic ulcer disease and its complications: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3:

231–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30037-2 - Fiedler KA, Maeng M, Mehilli J, Schulz-Schupke S, Byrne RA, Sibbing D, et al. Duration

of triple therapy in patients requiring oral anticoagulation after drug-eluting stent implantation: the ISAR-TRIPLE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1619–29. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.050

781. Matsumura-Nakano Y, Shizuta S, Komasa A, Morimoto T, Masuda H, Shiomi H, et al.

Open-label randomized trial comparing oral anticoagulation with and without single

antiplatelet therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease

beyond 1 year after coronary stent implantation. Circulation 2019;139:604–16. https://

doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036768

782. Jensen T, Thrane PG, Olesen KKW, Würtz M, Mortensen MB, Gyldenkerne C, et al.

Antithrombotic treatment beyond 1 year after percutaneous coronary intervention

in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2023;9:208–19.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvac058

783. Vitalis A, Shantsila A, Proietti M, Vohra RK, Kay M, Olshansky B, et al. Peripheral arterial

disease in patients with atrial fibrillation: the AFFIRM study. Am J Med 2021;134:514–8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.08.026

784. Wasmer K, Unrath M, Köbe J, Malyar NM, Freisinger E, Meyborg M, et al. Atrial fibrillation is a risk marker for worse in-hospital and long-term outcome in patients with

peripheral artery disease. Int J Cardiol 2015;199:223–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

ijcard.2015.06.094

785. Griffin WF, Salahuddin T, O’Neal WT, Soliman EZ. Peripheral arterial disease is associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Europace 2016;18:794–8.

https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euv369

786. Lin LY, Lee CH, Yu CC, Tsai CT, Lai LP, Hwang JJ, et al. Risk factors and incidence

of ischemic stroke in Taiwanese with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation—a nation wide

database analysis. Atherosclerosis 2011;217:292–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. atherosclerosis.2011.03.033

787. Su MI, Cheng YC, Huang YC, Liu CW. The impact of atrial fibrillation on one-year mortality in patients with severe lower extremity arterial disease. J Clin Med 2022;11:1936.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11071936

788. Winkel TA, Hoeks SE, Schouten O, Zeymer U, Limbourg T, Baumgartner I, et al.

Prognosis of atrial fibrillation in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: data from the REduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010;40:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2010. 03.003 - Nejim B, Mathlouthi A, Weaver L, Faateh M, Arhuidese I, Malas MB. Safety of carotid

artery revascularization procedures in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Vasc Surg 2020;

72:2069–2078.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.01.074 - Jones WS, Hellkamp AS, Halperin J, Piccini JP, Breithardt G, Singer DE, et al. Efficacy

and safety of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with peripheral artery

disease and non-valvular atrial fibrillation: insights from ROCKET AF. Eur Heart J

2014;35:242–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht492 - Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, Björck M, Brodmann M, Cohnert T, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries. Endorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO) The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J 2018;39:763–816. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ ehx095

- Schirmer CM, Bulsara KR, Al-Mufti F, Haranhalli N, Thibault L, Hetts SW. Antiplatelets

and antithrombotics in neurointerventional procedures: guideline update. J Neurointerv

Surg 2023;15:1155–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnis-2022-019844 - Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, De Marchis GM, Fonseca AC, Padiglioni C, et al.

European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute

ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J 2021;6:I–LXII. https://doi.org/10.1177/239698732198

9865