TS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

10. Tầm soát và ngăn ngừa AF

10.1. Dịch tễ học AF

Rung nhĩ là rối loạn nhịp tim dai dẳng phổ biến nhất trên toàn thế giới, với tỷ lệ lưu hành ước tính trên toàn cầu vào năm 2019 là 59,7 triệu người mắc AF. [1033] Các trường hợp mắc AF tăng gấp đôi sau mỗi vài thập kỷ. [1034] Dự kiến sẽ có sự gia tăng trong tương lai, đặc biệt là ở các quốc gia có thu nhập trung bình. [1034] Ở những cá nhân sống trong cộng đồng, tỷ lệ mắc AF trong nhóm đối tượng tại Hoa Kỳ lên tới 5,9%. [1035] Tỷ lệ mắc và tỷ lệ mắc chuẩn hóa theo độ tuổi vẫn không đổi theo thời gian. [1033,1036] Sự gia tăng về tỷ lệ mắc chung phần lớn là do sự gia tăng dân số, lão hóa và khả năng sống sót sau các tình trạng tim khác. Song song với đó, gánh nặng về yếu tố nguy cơ gia tăng, nhận thức tốt hơn và khả năng phát hiện AF được cải thiện đã được quan sát thấy. [1037] Nguy cơ mắc AF suốt đời được ước tính cao tới 1/3 đối với những người lớn tuổi, [1038] với tỷ lệ mắc chuẩn hóa theo độ tuổi cao hơn ở nam giới so với nữ giới. Dân số có tổ tiên là người châu Âu thường có tỷ lệ mắc AF cao hơn, những cá nhân có tổ tiên là người châu Phi có kết quả tệ hơn và các nhóm khác có thể ít được tiếp cận với các biện pháp can thiệp hơn. [1039–1041] Các yếu tố kinh tế xã hội và các yếu tố khác có thể đóng vai trò trong sự khác biệt về chủng tộc và dân tộc trong AF, nhưng các nghiên cứu cũng bị hạn chế do sự khác biệt về cách các nhóm tiếp cận dịch vụ chăm sóc sức khỏe. Sự thiếu hụt lớn hơn về tình trạng kinh tế xã hội và cuộc sống có liên quan đến tỷ lệ mắc AF cao hơn. [1042]

10.2. Các công cụ tầm soát AF

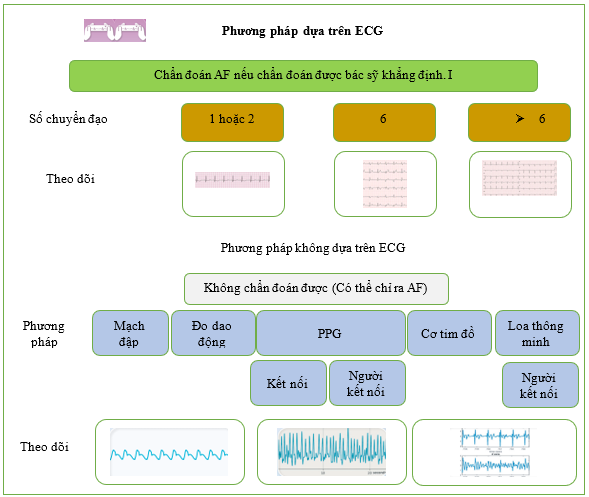

Trong những năm gần đây, rất nhiều thiết bị mới có thể theo dõi nhịp tim đã xuất hiện trên thị trường, gồm vòng đeo tay theo dõi sức khỏe và đồng hồ thông minh. Mặc dù bằng chứng về hiệu quả lâm sàng của các thiết bị kỹ thuật số còn hạn chế, nhưng chúng có thể hữu ích trong việc phát hiện AF và các tác động về mặt lâm sàng, kinh tế, pháp lý và chính sách của chúng đáng được nghiên cứu thêm. [1043,1044] Các thiết bị phát hiện AF có thể được chia thành các thiết bị cung cấp ECG và các thiết bị có phương pháp tiếp cận không phải ECG như quang thể tích (Hình 15 và Bảng 15).

Hầu hết các thiết bị dành cho người tiêu dùng đều sử dụng quang thể tích và một số nghiên cứu lớn đã được thực hiện thường ở những cá nhân có nguy cơ thấp. [633,1076,1117,1118] Trong một RCT gồm 5551 người tham gia được công ty bảo hiểm y tế của họ mời, quang thể tích dựa trên điện thoại thông minh đã làm tăng tỷ lệ mắc AF mới được điều trị bằng OAC lên 2,12 (95% CI, 1,19–3,76; P = .01) so với cách chăm sóc thông thường. [605] RCT được cung cấp để đánh giá kết quả lâm sàng vẫn còn thiếu đối với sàng lọc AF dựa trên người tiêu dùng. Cần có thêm các so sánh trực tiếp giữa các thiết bị kỹ thuật số mới và các thiết bị thường được sử dụng trong các cơ sở chăm sóc sức khỏe để thiết lập hiệu quả so sánh của chúng trong bối cảnh lâm sàng và tính đến các nhóm dân số và bối cảnh khác nhau. [1119] Trong một đánh giá có hệ thống về quang phổ kế dựa trên điện thoại thông minh so với ECG tham chiếu, độ nhạy và độ đặc hiệu cao không thực tế đã được ghi nhận, có thể là do các nghiên cứu nhỏ, chất lượng thấp với mức độ sai lệch lựa chọn bệnh nhân cao. [1120] Do đó, khi AF được gợi ý bởi thiết bị quang phổ kế hoặc bất kỳ công cụ sàng lọc nào khác, nên theo dõi ECG một chuyển đạo hoặc liên tục trong >30 giây hoặc ECG 12 chuyển đạo cho thấy AF do bác sĩ có chuyên môn về giải thích nhịp ECG phân tích để thiết lập chẩn đoán xác định AF. [1091,1121–1125]

Sự kết hợp giữa dữ liệu lớn và trí tuệ nhân tạo (AI) đang có tác động ngày càng tăng lên trong lĩnh vực điện sinh lý. Các thuật toán đã được tạo ra để cải thiện chẩn đoán AF tự động và một số thuật toán hỗ trợ chẩn đoán đang được nghiên cứu. [1046] Tuy nhiên, hiệu suất lâm sàng và khả năng áp dụng rộng rãi của các giải pháp này vẫn chưa được biết đến. Việc sử dụng AI có thể cho phép đánh giá những thay đổi trong điều trị trong tương lai bằng cách theo dõi liên tục và năng động theo chỉ đạo của bệnh nhân bằng các thiết bị đeo được.[1126] Vẫn còn những thách thức trong lĩnh vực này cần được làm rõ, chẳng hạn như thu thập dữ liệu, hiệu suất mô hình, tính hợp lệ bên ngoài, triển khai lâm sàng, giải thích thuật toán và sự tin cậy, cũng như các khía cạnh đạo đức.[1127]

Hình 15 Các phương pháp chẩn đoán không xâm lấn để sàng lọc AF.

Hình 15 Các phương pháp chẩn đoán không xâm lấn để sàng lọc AF.

AF: rung nhĩ; BP: huyết áp; ECG: điện tâm đồ; PPG ( ): quang thể tích ký

Bảng 15 Công cụ sàng lọc AF

| Công cụ tầm soát AF |

| (i) Bắt mạch [1045]

(ii) Sử dụng thuật toán trí tuệ nhân tạo để xác định bệnh nhân có nguy cơ [1046] (iii) Thiết bị dựa trên ECG (a) Thiết bị ECG thông thường (1) ECG 12 chuyển đạo kinh điển [1047] (2) Theo dõi Holter (từ 24 giờ đến một tuần hoặc lâu hơn) [1048] (3) Đo tim từ xa di động (trong thời gian nằm viện) [1049] (4) Thiết bị cầm tay [1050–1052] (5) Miếng dán có thể đeo được (lên đến 14 ngày) [1053–1067] (6) Vải sinh học (lên đến 30 ngày) [1068–1072] (7) Thiết bị thông minh (30 giây) [1073–1091] (b) Máy ghi vòng có thể cấy (3–5 tuổi) [1092–1099] (iv) Thiết bị không dựa trên ECG (a) Quang thể tích ký và thuật toán tự động: tiếp xúc (đầu ngón tay, thiết bị thông minh, băng tần) và không tiếp xúc (video) [1100–1106] (b) Đo dao động (máy đo huyết áp lấy được độ đều đặn của nhịp tim theo thuật toán) [1107–1110] (c) Cơ tim đồ (máy đo gia tốc và con quay hồi chuyển để cảm nhận hoạt động cơ học của tim) [1111] (d) Đo thể tích ký video không tiếp xúc (thông qua giám sát video) [1112–1115] (e) Loa thông minh (thông qua việc xác định các kiểu nhịp tim bất thường) [1116] |

10.3. Các chiến lược tầm soát AF

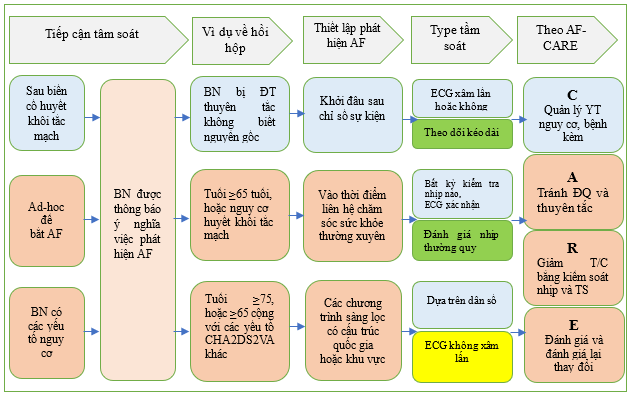

Việc sàng lọc có thể được thực hiện một cách có hệ thống, bằng cách gửi lời mời đến bệnh nhân hoặc theo cơ hội, tại thời điểm họp đột xuất với chuyên gia chăm sóc sức khỏe. Bất kể hình thức mời nào, việc sàng lọc phải là một phần của chương trình có cấu trúc [1128] và không giống như việc xác định AF trong quá trình khám sức khỏe định kỳ hoặc thứ phát sau các triệu chứng rối loạn nhịp tim.

Việc sàng lọc có thể được thực hiện tại một thời điểm duy nhất (ghi nhanh nhịp tim), ví dụ như bằng cách bắt mạch hoặc điện tâm đồ 12 chuyển đạo. Việc sàng lọc cũng có thể khoảng thời gian được mở rộng, tức là kéo dài, bằng cách theo dõi nhịp tim liên tục hoặc ngắt quãng. Hầu hết các nghiên cứu sử dụng chiến lược cơ hội đã sàng lọc AF tại một thời điểm duy nhất với thời gian ngắn (chẳng hạn như điện tâm đồ tại một thời điểm duy nhất), so với các nghiên cứu sàng lọc có hệ thống chủ yếu sử dụng đánh giá nhịp kéo dài (lặp lại hoặc liên tục). [1129] Phương pháp sàng lọc tối ưu sẽ thay đổi tùy thuộc vào quần thể được nghiên cứu (Hình 16) (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S32). Các phương pháp nhạy hơn sẽ phát hiện nhiều AF hơn nhưng có thể dẫn đến nguy cơ dương tính giả tăng lên và phát hiện AF gánh nặng thấp tăng lên, trong khi các phương pháp chuyên biệt hơn dẫn đến ít dương tính giả hơn, với nguy cơ bỏ sót AF.

Việc theo dõi nhịp tim xâm lấn ở những quần thể có nguy cơ cao kéo dài trong nhiều năm đã được chứng minh là dẫn đến tỷ lệ mắc AF được phát hiện bằng thiết bị là khoảng 30%, mặc dù hầu hết trong số họ có gánh nặng AF thấp. [5,857,1130,1131] Các nghiên cứu về máy tạo nhịp đã chỉ ra rằng những bệnh nhân có gánh nặng AF dưới lâm sàng được phát hiện bằng thiết bị thấp có nguy cơ đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ thấp hơn. [5,24,1131,1132] Điều này đã được xác nhận trong các RCT đánh giá việc sử dụng DOAC ở những bệnh nhân bị AF cận lâm sàng được phát hiện bằng thiết bị (xem Mục 6.1.1). [5,281,282] Gánh nặng cần thiết để AF dưới lâm sàng được phát hiện bằng thiết bị chuyển thành nguy cơ đột quỵ vẫn chưa được biết và rõ ràng là cần có thêm các nghiên cứu.[1133,1134] Lợi ích và hiệu quả về mặt chi phí của việc sàng lọc được thảo luận trong Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến.

Bảng khuyến cáo 31 — Khuyến cáo để sàng lọc AF (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 31)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Khuyến cáo bác sĩ nên xem lại ECG (12 chuyển đạo, một hoặc nhiều chuyển đạo) để đưa ra chẩn đoán xác định AF và bắt đầu điều trị phù hợp. [1091,1121–1123,1125] |

I |

B |

| Khuyến cáo đánh giá nhịp tim thường quy trong quá trình tiếp xúc với dịch vụ chăm sóc sức khỏe cho tất cả những người từ ≥65 tuổi để phát hiện sớm AF. |

I |

C |

| Cần cân nhắc sàng lọc AF dựa trên dân số bằng cách sử dụng phương pháp tiếp cận ECG không xâm lấn kéo dài ở những người từ ≥75 tuổi hoặc ≥65 tuổi có thêm các yếu tố nguy cơ CHA2DS2-VA để đảm bảo phát hiện sớm AF. [6,1135–1137] |

IIa |

B |

AF: rung nhĩ; CHA2DS2-VA: C: suy tim sung huyết, H: tăng huyết áp, A: tuổi ≥75 (2 điểm), D: đái tháo đường, S: đột quỵ/thiếu máu cục bộ thoáng qua/huyết khối động mạch (2 điểm), V: bệnh mạch máu, A: tuổi 65–74; ECG: điện tâm đồ.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng

Hình 16 Các phương pháp tiếp cận sàng lọc AF.

AF: rung nhĩ; AF-CARE: rung nhĩ—[C] Quản lý bệnh đi kèm và yếu tố nguy cơ, [A] Tránh đột quỵ và huyết khối tắc mạch, [R] Giảm các triệu chứng bằng cách kiểm soát nhịp và tần số, [E] Đánh giá và đánh giá lại thay đổi; CHA2DS2-VA: suy tim sung huyết, tăng huyết áp, tuổi ≥75 (2 điểm), đái tháo đường, đột quỵ/TIA/huyết khối tắc mạch động mạch trước đó (2 điểm), bệnh mạch máu, tuổi 65–74; ECG: điện tâm đồ. Xem Hình 15 để biết các phương pháp ECG không xâm lấn

10.3.1. ‘Ảnh chụp nhanh’ sàng lọc thời điểm đơn lẻ

Một số RCT theo cụm trong các cơ sở chăm sóc ban đầu đã khám phá xem liệu việc sàng lọc được thực hiện như một ảnh chụp nhanh nhịp tim tại một thời điểm có thể phát hiện ra nhiều AF hơn so với việc chăm sóc thông thường ở những cá nhân từ ≥65 tuổi hay không.[1138–1140] Không thấy phát hiện AF tăng lên ở các nhóm được phân ngẫu nhiên vào sàng lọc tại một thời điểm.[1138–1140] Những phát hiện này đã được xác nhận trong một phân tích tổng hợp các RCT cho thấy việc sàng lọc như một sự kiện một lần không làm tăng phát hiện AF so với việc chăm sóc thông thường. [1135] Đáng chú ý là các nghiên cứu này được thực hiện trong các cơ sở chăm sóc sức khỏe, nơi phát hiện AF trong quần thể có thể cao, do đó, kết quả có thể không thể khái quát hóa cho các cơ sở chăm sóc sức khỏe có phát hiện AF tự phát thấp hơn. Không có RCT nào giải quyết các kết quả lâm sàng ở những bệnh nhân bị AF được phát hiện bằng cách sàng lọc tại một thời điểm.[1123,1135]

10.3.2. Tầm soát kéo dài

Các nghiên cứu sử dụng sàng lọc kéo dài đã chỉ ra việc phát hiện AF tăng lên dẫn đến việc bắt đầu OAC.[1129, 1135,1141] Hai RCT đã nghiên cứu tác động đến kết quả lâm sàng trong việc sàng lọc AF kéo dài. [5,6] Trong thử nghiệm STROKESTOP (Sàng lọc ECG có hệ thống đối với rung nhĩ ở những đối tượng 75 tuổi tại khu vực Stockholm và Halland, Thụy Điển), những người 75 và 76 tuổi được phân ngẫu nhiên để được mời sàng lọc AF kéo dài bằng ECG một chuyển đạo hai lần mỗi ngày trong 2 tuần hoặc theo tiêu chuẩn chăm sóc. Sau trung bình 6,9 năm, có một sự giảm nhỏ về điểm cuối kết hợp chính là tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân, đột quỵ, thuyên tắc hệ thống và chảy máu nghiêm trọng có lợi cho việc sàng lọc kéo dài (HR, 0,96; 95% CI, 0,92–1,00; P = 0,045). [6] Trong thử nghiệm LOOP (Phát hiện rung nhĩ bằng theo dõi điện tâm đồ liên tục), những cá nhân có nguy cơ đột quỵ cao được phân ngẫu nhiên để nhận máy ghi vòng cấy ghép theo dõi nhịp tim trong trung bình 3,3 năm hoặc nhóm đối chứng được chăm sóc tiêu chuẩn. Mặc dù có tỷ lệ phát hiện AF cao hơn (31,8%) và bắt đầu OAC sau đó ở nhóm máy ghi vòng so với nhóm chăm sóc tiêu chuẩn (12,2%), điều này không đi kèm với sự khác biệt về kết quả chính là đột quỵ hoặc thuyên tắc hệ thống. [5] Trong phân tích tổng hợp các RCT gần đây về kết quả của đột quỵ, một lợi ích nhỏ nhưng đáng kể đã được thấy có lợi cho việc sàng lọc kéo dài (RR, 0,91; 95% CI, 0,84–0,99). [1136] Điều này không được lặp lại trong phân tích tổng hợp thứ hai bao gồm các RCT cũ hơn, trong đó không thấy giảm nguy cơ liên quan đến tử vong hoặc đột quỵ. [1135] Đáng chú ý, cả hai phân tích tổng hợp này có khả năng không đủ mạnh để đánh giá kết quả lâm sàng.

10.4. Các yếu tố liên quan đến AF có thể xẩy ra

Các yếu tố dự báo nguy cơ phổ biến nhất đối với AF mới mắc (mới khởi phát) được thể hiện trong Bảng 16. Mặc dù các yếu tố được liệt kê có liên quan chặt chẽ với AF mới mắc trong các nghiên cứu quan sát, nhưng không biết liệu các mối quan hệ này có phải là nhân quả hay không. Các nghiên cứu sử dụng phương pháp ngẫu nhiên Mendel (các đại diện di truyền cho các yếu tố nguy cơ để ước tính các tác động nhân quả) cho thấy rõ ràng BP tâm thu và BMI cao hơn là các yếu tố nguy cơ nhân quả đối với AF mới mắc.[1142] Mức độ tương tác cao xảy ra giữa tất cả các yếu tố liên quan đến sự phát triển AF (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S33).[1038,1039,1143–1145] Để dễ áp dụng lâm sàng, các công cụ dự báo nguy cơ đã kết hợp nhiều yếu tố khác nhau và gần đây đã sử dụng các thuật toán học máy để dự báo. [1146,1147] Các điểm số nguy cơ cổ điển cũng khả dụng với khả năng dự báo biến đổi và hiệu suất mô hình (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng S7).[1148] Các kết quả được cải thiện khi sử dụng các điểm số nguy cơ này vẫn chưa được chứng minh. Mặc dù kiến thức về cơ sở di truyền của AF ở một số bệnh nhân đang tăng nhanh, nhưng giá trị của sàng lọc di truyền hiện vẫn còn hạn chế (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến)

Bảng 16: Các yếu tố liên quan đến AF có thể xẩy ra

| Yếu tố nhân khẩu học

|

Tuổi [1149–1151] |

| Giới tính nam [1149–1152] | |

| Tổ tiên là người châu Âu [1149,1150] | |

| Địa vị kinh tế xã hội thấp hơn [1150] | |

| Hành vi thói quen sống | Hút thuốc /sử dụng thuốc lá [1149–1151] |

| Uống rượu [1149,1150] | |

| Không hoạt động thể lực [1149,1150] | |

| Tập thể dục mạnh [1153–1156] | |

| Thể thao sức bền cạnh tranh hoặc cấp độ vận động viên [1151,1157] | |

| Cafê [1158–1160] | |

| Bệnh đi kèm và các yếu tố nguy cơ | Tăng huyết áp [1149–1151] |

| Suy tim [178,1149–1151,1161] | |

| Bệnh van tim [1149,1151,1162–1164] | |

| Bệnh động mạch vành [1149, 1151, 1161, 1165] | |

| Bệnh động mạch ngoại biên [785]

Bệnh tim bẩm sinh [1149,1166] |

|

| Nhịp tim, biến thiên nhịp tim [1167,1168] | |

| Tổng lượng cholesterol [1149,1150] | |

| Cholesterol lipoprotein tỷ trọng thấp [1150] | |

| Cholesterol lipoprotein tỷ trọng cao [1150] | |

| Triglyceride [1150] | |

| Rối loạn dung nạp glucose, [1169–1172] bệnh tiểu đường [1149–1151,1169] | |

| Rối loạn chức năng thận/CKD [1149–1151,1173,1174] | |

| Béo phì [1149–1151,1175,1176] | |

| Chỉ số khối cơ thể, cân nặng [1149–1151] | |

| Chiều cao [1150] | |

| Ngưng thở khi ngủ [1149,1151,1177,1178] | |

| Bệnh phổi tắc nghẽn mãn tính [1179] | |

| Xơ vữa động mạch dưới lâm sàng

|

Vôi hóa động mạch vành [1149, 1151, 1180] |

| IMT động mạch cảnh và mảng bám động mạch cảnh [1149, 1151, 1181, 1182] | |

| Bất thường ECG

|

Kéo dài khoảng PR [1149, 1151,1183] |

| Hội chứng xoang bệnh lý [1149,1184,1185] | |

| Wolff–Parkinson–White [1149,1186] | |

| Yếu tố di truyền

|

Tiền sử gia đình mắc AF [1149,1151,1187–1190] |

| Các vị trí dễ mắc AF được xác định bằng GWAS [1149, 1151, 1191, 1192] | |

| Hội chứng QT ngắn [1149] | |

| Bệnh cơ tim di truyền [990,1193] | |

| Chỉ dấu sinh học

|

Protein phản ứng C (CRP) [1150,1151] |

| Fibrinogen [1150] | |

| Yếu tố biệt hóa tăng trưởng- [151194] | |

| Peptit natri lợi tiểu (tâm nhĩ và loại B) [1195–1200] | |

| Troponin tim [1199] | |

| Sinh học chỉ điểm viêm [1149,1151] | |

| Các yếu tố khác

|

Rối loạn chức năng tuyến giáp [912,1149–1151] |

| Bệnh tự miễn [1150] | |

| Ô nhiễm không khí [1149,1201] | |

| Nhiễm trùng huyết [1149,1202] | |

| Yếu tố tâm lý [1203,1204] |

AF: rung nhĩ; CKD: bệnh thận mãn tính; GWAS (genome-wide association studies): nghiên cứu liên kết toàn bộ hệ gen; HF: suy tim; IMT (intima-media thickness): độ dày lớp nội trung mạc.

10.5. Ngăn ngừa AF tiên phát

Ngăn ngừa khởi phát AF trước khi biểu hiện lâm sàng có tiềm năng rõ ràng trong việc cải thiện cuộc sống của dân số nói chung và giảm đáng kể chi phí chăm sóc sức khỏe và xã hội liên quan đến sự phát triển của AF. Trong khi [C] trong AF-CARE tập trung vào việc quản lý hiệu quả các yếu tố nguy cơ và bệnh đi kèm để hạn chế tái phát và tiến triển AF, cũng có bằng chứng cho thấy chúng có thể được nhắm mục tiêu để ngăn ngừa AF. Dữ liệu có sẵn được trình bày bên dưới về tăng huyết áp, suy tim, đái tháo đường týp 2, béo phì, hội chứng ngưng thở khi ngủ, hoạt động thể chất và rượu, mặc dù nhiều dấu hiệu nguy cơ khác cũng có thể được nhắm mục tiêu. Thông tin thêm về nguy cơ có thể quy cho AF của từng yếu tố được cung cấp trong dữ liệu Bổ sung trực tuyến (xem Dữ liệu Bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng Bằng chứng 32 và các Bảng Bằng chứng bổ sung S34–S39)

Bảng khuyến cáo 32 — Khuyến cáo để phòng ngừa AF nguyên phát (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 32)

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Duy trì huyết áp tối ưu được khuyến cáo trong quần thể chung để ngăn ngừa AF, với thuốc ức chế men chuyển ACE hoặc ARB là liệu pháp hàng đầu. [1205–1207] |

I |

B |

| Liệu pháp y tế HF phù hợp được khuyến cáo ở những người bị HFrEF để ngăn ngừa AF. [133,136,1208–1211] |

I |

B |

| Duy trì cân nặng bình thường (BMI 20–25 kg/m2) được khuyến cáo cho quần thể chung để ngăn ngừa AF. [208,1212,1213] |

I |

B |

| Duy trì thói quen sống năng động được khuyến cáo để ngăn ngừa AF, với cường độ vừa phải tương đương 150–300 phút mỗi tuần hoặc cường độ mạnh tương đương 75–150 phút mỗi tuần. [1214–1219] |

I |

B |

| Tránh uống rượu quá độ và uống quá nhiều rượu được khuyến cáo cho quần thể chung để ngăn ngừa AF. [1220–1223] |

I |

B |

| Cần cân nhắc sử dụng thuốc ức chế SGLT2 hoặc Metformin cho những cá nhân cần quản lý dược lý bệnh tiểu đường để ngăn ngừa AF. [1210,1211,1224–1226] |

IIa |

B |

| Cần cân nhắc giảm cân ở những người béo phì để ngăn ngừa AF. [1212,1227–1231] |

IIa |

B |

ACE: men chuyển angiotensin; AF: rung nhĩ; ARB: thuốc chẹn thụ thể angiotensin; BMI: chỉ số khối cơ thể; HF: suy tim; HFrEF: suy tim có phân suất tống máu giảm; SGLT2: đồng vận chuyển natri-glucose-2.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

10.5.1. Tăng huyết áp

Việc quản lý tăng huyết áp có liên quan đến việc giảm AF mới mắc. [1205–1207,1232] Trong thử nghiệm LIFE (Losartan Intervention for End point reduction in hypertension: Can thiệp Losartan để giảm tiêu chí cuối trong tăng huyết áp), việc giảm 10 mmHg huyết áp tâm thu có liên quan đến việc giảm 17% AF mới mắc. [1207] Phân tích thứ cấp các RCT và các nghiên cứu quan sát cho thấy thuốc ức chế ACE hoặc ARB có thể tốt hơn thuốc chẹn beta, thuốc chẹn kênh canxi hoặc thuốc lợi tiểu trong việc ngăn ngừa AF mới mắc. [1233–1236]

10.5.2. Suy tim

Các phương pháp điều trị dược lý đã được thiết lập từ lâu đối với HFrEF có liên quan đến việc giảm AF mới mắc. Việc sử dụng thuốc ức chế ACE hoặc ARB ở những bệnh nhân đã biết bị HFrEF có liên quan đến

giảm 44% tỷ lệ mắc AF. [1208] Tương tự như vậy, thuốc chẹn beta ở HFrEF dẫn đến giảm 33% tỷ lệ mắc AF mới mắc. [133] Thuốc đối kháng thụ thể mineralocorticoid cũng đã được chứng minh là làm giảm nguy cơ mắc AF mới mắc tới 42% ở những bệnh nhân bị HFrEF. [1209] Mặc dù có những tác dụng khác nhau của thuốc ức chế SGLT2 đối với AF mới mắc, một số phân tích tổng hợp đã chứng minh rằng có sự giảm 18%–37% AF mới mắc. [136,1210,1211,1237] Tuy nhiên, việc điều trị HFrEF bằng sacubitril/valsartan vẫn chưa được chứng minh là mang lại bất kỳ lợi ích bổ sung nào trong việc giảm AF mới khởi phát khi so sánh với thuốc ức chế ACE/ARB đơn thuần. [1238] Có một số bằng chứng cho thấy CRT hiệu quả ở những bệnh nhân đủ điều kiện mắc HFrEF làm giảm nguy cơ AF mới khởi phát. [1239] Cho đến nay, chưa có phương pháp điều trị nào ở HFpEF được chứng minh là làm giảm AF mới khởi phát.

10.5.3. Đái tháo đường týp 2

Chăm sóc tích hợp cho bệnh đái tháo đường týp 2, dựa trên lối sống và các phương pháp điều trị dược lý cho các bệnh đi kèm như béo phì, tăng huyết áp và rối loạn lipid máu, là những bước hữu ích trong việc ngăn ngừa tái cấu trúc tâm nhĩ và AF sau đó. Liệu pháp hạ glucose chuyên sâu nhắm mục tiêu mức HbA1c <6,0% (<42 mmol/mol) không cho thấy tác dụng bảo vệ đối với AF mới mắc. [1240] Hơn cả việc kiểm soát đường huyết, nhóm thuốc hạ glucose có thể ảnh hưởng đến nguy cơ AF. [1240] Insulin thúc đẩy quá trình hình thành mỡ và xơ hóa tim, và sulfonylurea luôn liên quan đến việc tăng nguy cơ AF. [193] Các nghiên cứu quan sát đã liên kết metformin với tỷ lệ AF mới mắc thấp hơn. [1224,1225,1241–1243] Nhiều nghiên cứu và phân tích tổng hợp gần đây chỉ ra vai trò tích cực của chất ức chế SGLT2 trong việc giảm nguy cơ AF mới mắc ở bệnh nhân tiểu đường và không tiểu đường. [136, 1226, 1244–1246] Dữ liệu gộp từ 22 thử nghiệm gồm 52 951 bệnh nhân mắc bệnh tiểu đường type 2 và suy tim cho thấy thuốc ức chế SGLT2 so với giả dược có thể làm giảm đáng kể tỷ lệ mắc AF tới 18% trong các nghiên cứu về bệnh tiểu đường và lên tới 37% ở bệnh nhân suy tim có hoặc không có bệnh tiểu đường loại 2. [1210,1211]

10.5.4. Béo phì

Quản lý cân nặng là điều quan trọng trong việc phòng ngừa AF. Trong một nghiên cứu theo nhóm dân số lớn, cân nặng bình thường có liên quan đến việc giảm nguy cơ AF mới mắc so với những người béo phì (tăng 4,7% nguy cơ AF mới mắc cho mỗi 1 kg/m2 BMI tăng).[208] Trong Nghiên cứu Sức khỏe Phụ nữ, những người tham gia bị béo phì có nguy cơ AF mới mắc tăng 41% so với những người duy trì BMI <30 kg/m2.[1212] Tương tự như vậy, các nghiên cứu quan sát trong các quần thể sử dụng phẫu thuật bariatric để giảm cân ở những người béo phì bệnh lý (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) đã quan sát thấy nguy cơ AF mới mắc thấp hơn.[1227–1231]

10.5.5. Hội chứng ngưng thở khi ngủ

Mặc dù có vẻ hợp lý khi tối ưu hóa thói quen ngủ, nhưng cho đến nay vẫn chưa có bằng chứng kết luận nào ủng hộ điều này để phòng ngừa tiên phát AF. Thử nghiệm SAVE (Sleep Apnea cardioVascular Endpoints: Tiêu chí tim mạch ngưng thở khi ngủ) đã không chứng minh được sự khác biệt về kết quả lâm sàng ở những người được phân ngẫu nhiên dùng liệu pháp CPAP hoặc giả dược.[230] Không có sự khác biệt về AF mới mắc, mặc dù phân tích AF không dựa trên sàng lọc có hệ thống mà dựa trên AF được ghi nhận trên lâm sàng.

10.5.6. Hoạt động thể chất

Một số nghiên cứu đã chứng minh tác dụng có lợi của hoạt động thể chất vừa phải đối với sức khỏe tim mạch.[1247] Bài tập aerobic vừa phải cũng có thể làm giảm nguy cơ AF mới khởi phát. [1214–1219] Cần lưu ý rằng tỷ lệ AF dường như tăng lên ở các vận động viên, với phân tích tổng hợp các nghiên cứu quan sát cho thấy nguy cơ AF tăng gấp 2,5 lần so với nhóm đối chứng không phải vận động viên.[1248]

10.5.7. Lượng rượu uống vào

Tiền đề cho rằng việc giảm lượng rượu uống vào có thể ngăn ngừa AF dựa trên các nghiên cứu quan sát liên kết rượu với nguy cơ mắc AF cao hơn theo cách phụ thuộc vào liều lượng (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến). [1220–1222] Ngoài ra, một nghiên cứu nhóm dân số về những người tiêu thụ nhiều rượu (>60 g/ngày đối với nam giới và >40 g/ngày đối với nữ giới) đã phát hiện ra việc kiêng rượu có liên quan đến tỷ lệ mắc AF thấp hơn so với những bệnh nhân tiếp tục uống nhiều rượu.[1223]

11. Thông điệp quan trọng

(1) Quản lý chung: điều trị tối ưu theo lộ trình AF-CARE, bao gồm: [C] Quản lý bệnh đi kèm và yếu tố nguy cơ; [A] Tránh đột quỵ và huyết khối tắc mạch; [R] Giảm các triệu chứng bằng cách kiểm soát nhịp tim và tần số; và [E] Đánh giá và đánh giá lại động học.

(2) Chăm sóc chung: quản lý AF lấy bệnh nhân làm trung tâm với quá trình ra quyết định chung và một nhóm đa ngành.

(3) Chăm sóc bình đẳng: tránh bất bình đẳng về sức khỏe dựa trên giới tính, dân tộc, khuyết tật và các yếu tố kinh tế xã hội.

(4) Giáo dục: dành cho bệnh nhân, thành viên gia đình, người chăm sóc và chuyên gia chăm sóc sức khỏe để hỗ trợ quá trình ra quyết định chung.

(5) Chẩn đoán: AF lâm sàng cần xác nhận trên thiết bị ECG để bắt đầu phân tầng nguy cơ và quản lý AF.

(6) Đánh giá ban đầu: bệnh sử, đánh giá các triệu chứng và tác động của chúng, xét nghiệm máu, siêu âm tim/hình ảnh khác, các biện pháp đánh giá kết quả do bệnh nhân báo cáo và các yếu tố nguy cơ gây huyết khối tắc mạch và chảy máu.

(7) Bệnh đi kèm và các yếu tố nguy cơ: đánh giá và quản lý kỹ lưỡng có vai trò quan trọng đối với mọi khía cạnh chăm sóc bệnh nhân AF để tránh tái phát và tiến triển AF, cải thiện thành công của các phương pháp điều trị AF và ngăn ngừa các kết quả bất lợi liên quan đến AF.

(8) Tập trung vào các tình trạng liên quan đến AF: bao gồm tăng huyết áp, suy tim, đái tháo đường, béo phì, ngưng thở tắc nghẽn khi ngủ, ít vận động và uống nhiều rượu.

(9) Đánh giá nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch: sử dụng các công cụ đánh giá nguy cơ đã được xác nhận tại địa phương hoặc điểm CHA2DS2-VA và đánh giá các yếu tố nguy cơ khác, đánh giá lại theo định kỳ để hỗ trợ quyết định kê đơn thuốc chống đông.

(10) Thuốc chống đông đường uống: khuyến cáo cho tất cả bệnh nhân đủ điều kiện, ngoại trừ những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ đột quỵ hoặc huyết khối tắc mạch thấp

(Cần cân nhắc dùng CHA2DS2-VA = 1 thuốc chống đông; khuyến cáo dùng CHA2DS2-VA ≥2 thuốc chống đông).

(11) Lựa chọn thuốc chống đông: DOAC (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban và rivaroxaban) được ưu tiên hơn VKA (warfarin và các loại khác), ngoại trừ ở những bệnh nhân có van tim cơ học và hẹp van hai lá.

(12) Liều lượng/phạm vi thuốc chống đông: sử dụng liều chuẩn đầy đủ cho DOAC trừ khi bệnh nhân đáp ứng các tiêu chí giảm liều cụ thể; đối với VKA, giữ INR thường là 2,0–3,0 và trong phạm vi trong >70% thời gian.

(13) Chuyển thuốc chống đông: chuyển từ VKA sang DOAC nếu có nguy cơ xuất huyết nội sọ hoặc kiểm soát kém mức INR.

(14) Nguy cơ chảy máu: các yếu tố nguy cơ chảy máu có thể thay đổi nên được quản lý để cải thiện độ an toàn; không nên sử dụng điểm số nguy cơ chảy máu để quyết định bắt đầu hoặc ngừng thuốc chống đông.

(15) Liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu: tránh kết hợp thuốc chống đông máu và thuốc chống tiểu cầu, trừ khi bệnh nhân bị biến cố mạch máu cấp tính hoặc cần điều trị tạm thời cho các thủ thuật liên tục uống nhiều rượu.[1223]

(16) Liệu pháp kiểm soát tần số: sử dụng thuốc chẹn beta (bất kỳ phân suất tống máu nào), digoxin (bất kỳ phân suất tống máu nào) hoặc diltiazem/verapamil (LVEF >40%)

như liệu pháp ban đầu trong trường hợp cấp tính, liệu pháp bổ sung cho liệu pháp kiểm soát nhịp tim hoặc như một chiến lược điều trị duy nhất để kiểm soát tần số tim và các triệu chứng.

(17) Kiểm soát nhịp tim: xem xét ở tất cả các bệnh nhân AF phù hợp, thảo luận rõ ràng với bệnh nhân về tất cả các lợi ích và nguy cơ tiềm ẩn của việc chuyển nhịp, thuốc chống loạn nhịp và triệt phá qua catheter hoặc phẫu thuật để giảm các triệu chứng và bệnh tật.

(18) An toàn là trên hết: luôn ghi nhớ sự an toàn và chống đông máu khi cân nhắc kiểm soát nhịp tim; ví dụ, trì hoãn chuyển nhịp và cung cấp ít nhất 3 tuần thuốc chống đông trước nếu thời gian AF >24 giờ và xem xét độc tính và tương tác thuốc đối với liệu pháp chống loạn nhịp.

(19) Chuyển nhịp: sử dụng chuyển nhịp bằng điện trong trường hợp mất ổn định huyết động; nếu không, hãy chọn chuyển nhịp bằng điện hoặc dược lý dựa trên đặc điểm và sở thích của bệnh nhân.

(20) Chỉ định kiểm soát nhịp tim dài hạn: chỉ định chính nên là giảm các triệu chứng liên quan đến AF và cải thiện chất lượng cuộc sống; đối với các nhóm bệnh nhân được chọn, có thể theo đuổi việc duy trì nhịp xoang để giảm tỷ lệ mắc bệnh và tử vong.

(21) Kiểm soát nhịp tim thành công hay thất bại: tiếp tục chống đông theo nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch của từng bệnh nhân, bất kể họ đang ở AF hay nhịp xoang.

(22) Triệt phá qua catheter: xem xét như lựa chọn hàng thứ hai nếu thuốc chống loạn nhịp không kiểm soát được AF hoặc lựa chọn hàng đầu ở những bệnh nhân AF kịch phát.

(23) Triệt phá qua nội soi hoặc kết hợp: xem xét nếu triệt phá qua catheter không thành công hoặc là phương pháp thay thế cho triệt phá qua catheter ở những bệnh nhân AF dai dẳng mặc dù đã dùng thuốc chống loạn nhịp.

(24) Triệt phá rung nhĩ trong phẫu thuật tim: thực hiện tại các trung tâm có đội ngũ giàu kinh nghiệm, đặc biệt là đối với những bệnh nhân đang phẫu thuật van hai lá.

(25) Đánh giá động: đánh giá lại liệu pháp định kỳ và chú ý đến các yếu tố rủi ro mới có thể thay đổi được có thể làm chậm/đảo ngược sự tiến triển của AF, tăng chất lượng cuộc sống và ngăn ngừa các kết quả bất lợi.

(Vui lòng xem tiếp trong kỳ sau)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO:

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2982–3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

1034. Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Cervellin G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke 2021;16:217–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493019897870

1035. Alonso A, Alam AB, Kamel H, Subbian V, Qian J, Boerwinkle E, et al. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the all of US research program. PLoS One 2022;17:e0265498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265498

1036. Ghelani KP, Chen LY, Norby FL, Soliman EZ, Koton S, Alonso A. Thirty-year trends in the incidence of atrial fibrillation: the ARIC study. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;11:e023583. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.023583

1037. Williams BA, Chamberlain AM, Blankenship JC, Hylek EM, Voyce S. Trends in atrial fibrillation incidence rates within an integrated health care delivery system, 2006 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2014874. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14874

1038. Magnussen C, Niiranen TJ, Ojeda FM, Gianfagna F, Blankenberg S, Njølstad I, et al. Sex differences and similarities in atrial fibrillation epidemiology, risk factors, and mortality in community cohorts: results from the BiomarCaRE consortium (Biomarker for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe). Circulation 2017;136:1588–97. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028981

1039. Rodriguez CJ, Soliman EZ, Alonso A, Swett K, Okin PM, Goff DC, Jr, et al. Atrial fibrillation incidence and risk factors in relation to race-ethnicity and the population attributable fraction of atrial fibrillation risk factors: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Ann Epidemiol 2015;25:71–6, 76.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. annepidem.2014.11.024 - Ugowe FE, Jackson LR, 2nd, Thomas KL. Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence, management, and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Heart Rhythm 2018;15:1337–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.019

1041. Volgman AS, Bairey Merz CN, Benjamin EJ, Curtis AB, Fang MC, Lindley KJ, et al. Sex and race/ethnicity differences in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2812–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.045

1042. Chung SC, Sofat R, Acosta-Mena D, Taylor JA, Lambiase PD, Casas JP, et al. Atrial fibrillation epidemiology, disparity and healthcare contacts: a population-wide study of 5.6 million individuals. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021;7:100157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100157

1043. Svennberg E, Tjong F, Goette A, Akoum N, Di Biase L, Bordachar P, et al. How to use digital devices to detect and manage arrhythmias: an EHRA practical guide. Europace 2022;24:979–1005. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euac038 - Spatz ES, Ginsburg GS, Rumsfeld JS, Turakhia MP. Wearable digital health technologies for monitoring in cardiovascular medicine. N Engl J Med 2024;390:346–56. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2301903

1045. Cooke G, Doust J, Sanders S. Is pulse palpation helpful in detecting atrial fibrillation? A systematic review. J Fam Pract 2006;55:130–4. - Attia ZI, Noseworthy PA, Lopez-Jimenez F, Asirvatham SJ, Deshmukh AJ, Gersh BJ, et al. An artificial intelligence-enabled ECG algorithm for the identification of patients with atrial fibrillation during sinus rhythm: a retrospective analysis of outcome prediction. Lancet 2019;394:861–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31721-0

- Hobbs FD, Fitzmaurice DA, Mant J, Murray E, Jowett S, Bryan S, et al. A randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study of systematic screening (targeted and total population screening) versus routine practice for the detection of atrial fibrillation in people aged 65 and over. The SAFE study. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:iii–iv, ix-x, 1–74. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta9400

- Grond M, Jauss M, Hamann G, Stark E, Veltkamp R, Nabavi D, et al. Improved detection of silent atrial fibrillation using 72-hour Holter ECG in patients with ischemic stroke: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Stroke 2013;44:3357–64. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001884

1049. Rizos T, Guntner J, Jenetzky E, Marquardt L, Reichardt C, Becker R, et al. Continuous stroke unit electrocardiographic monitoring versus 24-hour Holter electrocardiography for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after stroke. Stroke 2012;43: 2689–94. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.654954 - Doliwa PS, Frykman V, Rosenqvist M. Short-term ECG for out of hospital detection of silent atrial fibrillation episodes. Scand Cardiovasc J 2009;43:163–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14017430802593435

1051. Tieleman RG, Plantinga Y, Rinkes D, Bartels GL, Posma JL, Cator R, et al. Validation and clinical use of a novel diagnostic device for screening of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2014;16:1291–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euu057 - Kearley K, Selwood M, Van den Bruel A, Thompson M, Mant D, Hobbs FR, et al. Triage tests for identifying atrial fibrillation in primary care: a diagnostic accuracy study comparing single-lead ECG and modified BP monitors. BMJ Open 2014;4: e004565. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004565

- Barrett PM, Komatireddy R, Haaser S, Topol S, Sheard J, Encinas J, et al. Comparison of 24-hour Holter monitoring with 14-day novel adhesive patch electrocardiographic monitoring. Am J Med 2014;127:95.e11–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.003

1054. Turakhia MP, Hoang DD, Zimetbaum P, Miller JD, Froelicher VF, Kumar UN, et al.Diagnostic utility of a novel leadless arrhythmia monitoring device. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:520–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.04.017 - Rosenberg MA, Samuel M, Thosani A, Zimetbaum PJ. Use of a noninvasive continuous monitoring device in the management of atrial fibrillation: a pilot study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2013;36:328–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/pace.12053

- Turakhia MP, Ullal AJ, Hoang DD, Than CT, Miller JD, Friday KJ, et al. Feasibility of extended ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring to identify silent atrial fibrillation in high-risk patients: the Screening Study for Undiagnosed Atrial Fibrillation (STUDY-AF). Clin Cardiol 2015;38:285–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22387

- Rooney MR, Soliman EZ, Lutsey PL, Norby FL, Loehr LR, Mosley TH, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of subclinical atrial fibrillation in a community-dwelling elderly population: the ARIC study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2019;12:e007390. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007390

- Stehlik J, Schmalfuss C, Bozkurt B, Nativi-Nicolau J, Wohlfahrt P, Wegerich S, et al. Continuous wearable monitoring analytics predict heart failure hospitalization: the LINK-HF multicenter study. Circ Heart Fail 2020;13:e006513. https://doi.org/101161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006513

1059. Ganne C, Talkad SN, Srinivas D, Somanna S. Ruptured blebs and racing hearts: autonomic cardiac changes in neurosurgeons during microsurgical clipping of aneurysms. Br J Neurosurg 2016;30:450–2. https://doi.org/10.3109/02688697.2016.1159656 - Smith WM, Riddell F, Madon M, Gleva MJ. Comparison of diagnostic value using a small, single channel, P-wave centric sternal ECG monitoring patch with a standard 3-lead Holter system over 24 hours. Am Heart J 2017;185:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.11.006

1061. Olson JA, Fouts AM, Padanilam BJ, Prystowsky EN. Utility of mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry for the diagnosis of palpitations, presyncope, syncope, and the assessment of therapy efficacy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2007;18:473–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00779.x

1062. Derkac WM, Finkelmeier JR, Horgan DJ, Hutchinson MD. Diagnostic yield of asymptomatic arrhythmias detected by mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry and autotrigger looping event cardiac monitors. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2017;28:1475–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.13342

1063. Teplitzky BA, McRoberts M, Ghanbari H. Deep learning for comprehensive ECG annotation. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:881–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.02.015

1064. Jeon E, Oh K, Kwon S, Son H, Yun Y, Jung ES, et al. A lightweight deep learning model for fast electrocardiographic beats classification with a wearable cardiac monitor: development and validation study. JMIR Med Inform 2020;8:e17037. https://doi.org/10.2196/17037 - Breteler MJMM, Huizinga E, van Loon K, Leenen LPH, Dohmen DAJ, Kalkman CJ, et al. Reliability of wireless monitoring using a wearable patch sensor in high-risk surgical patients at a step-down unit in The Netherlands: a clinical validation study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020162. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020162

- Hopkins L, Stacey B, Robinson DBT, James OP, Brown C, Egan RJ, et al. Consumer-grade biosensor validation for examining stress in healthcare professionals. Physiol Rep 2020;8:e14454. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.14454

- Steinhubl SR, Waalen J, Edwards AM, Ariniello LM, Mehta RR, Ebner GS, et al. Effect of a home-based wearable continuous ECG monitoring patch on detection of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation: the mSToPS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;320: 146–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.8102

- Elliot CA, Hamlin MJ, Lizamore CA. Validity and reliability of the hexoskin wearable biometric vest during maximal aerobic power testing in elite cyclists. J Strength Cond Res 2019;33:1437–44. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002005

- Eysenck W, Freemantle N, Sulke N. A randomized trial evaluating the accuracy of AF detection by four external ambulatory ECG monitors compared to permanent pacemaker AF detection. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2020;57:361–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-019-00515-0

1070. Fabregat-Andres O, Munoz-Macho A, Adell-Beltran G, Ibanez-Catala X, Macia A, Facila L. Evaluation of a new shirt-based electrocardiogram device for cardiac screening in soccer players: comparative study with treadmill ergospirometry. Cardiol Res 2014;5:101–7. https://doi.org/10.14740/cr333w - Feito Y, Moriarty TA, Mangine G, Monahan J. The use of a smart-textile garment during high-intensity functional training: a pilot study. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2019;59: 947–54. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.18.08689-9

- Pagola J, Juega J, Francisco-Pascual J, Moya A, Sanchis M, Bustamante A, et al. Yield of atrial fibrillation detection with textile wearable Holter from the acute phase of stroke: pilot study of crypto-AF registry. Int J Cardiol 2018;251:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.10.063

- Lau JK, Lowres N, Neubeck L, Brieger DB, Sy RW, Galloway CD, et al. iphone ECG application for community screening to detect silent atrial fibrillation: a novel technology to prevent stroke. Int J Cardiol 2013;165:193–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.220

- Bumgarner JM, Lambert CT, Hussein AA, Cantillon DJ, Baranowski B, Wolski K, et al.Smartwatch algorithm for automated detection of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2381–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.003

- Lubitz SA, Faranesh AZ, Atlas SJ, McManus DD, Singer DE, Pagoto S, et al. Rationale and design of a large population study to validate software for the assessment of atrial fibrillation from data acquired by a consumer tracker or smartwatch: the Fitbit heart study. Am Heart J 2021;238:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2021.04.003

- Perez MV, Mahaffey KW, Hedlin H, Rumsfeld JS, Garcia A, Ferris T, et al. Large-scale assessment of a smartwatch to identify atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2019;381: 1909–17. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1901183

- Saghir N, Aggarwal A, Soneji N, Valencia V, Rodgers G, Kurian T. A comparison of manual electrocardiographic interval and waveform analysis in lead 1 of 12-lead ECG and apple watch ECG: a validation study. Cardiovasc Digit Health J 2020;1: 30–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvdhj.2020.07.002

- Seshadri DR, Bittel B, Browsky D, Houghtaling P, Drummond CK, Desai MY, et al. Accuracy of apple watch for detection of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2020;141:702–3. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044126

- Zhang H, Zhang J, Li HB, Chen YX, Yang B, Guo YT, et al. Validation of single centre pre-mobile atrial fibrillation apps for continuous monitoring of atrial fibrillation in a real-world setting: pilot cohort study. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e14909. https://doi.org/10.2196/14909

- Fan YY, Li YG, Li J, Cheng WK, Shan ZL, Wang YT, et al. Diagnostic performance of a smart device with photoplethysmography technology for atrial fibrillation detection: pilot study (Pre-mAFA II registry). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e11437. https://doi.org/10.2196/11437

1081. Brito R, Mondouagne LP, Stettler C, Combescure C, Burri H. Automatic atrial fibrillation and flutter detection by a handheld ECG recorder, and utility of sequential finger and precordial recordings. J Electrocardiol 2018;51:1135–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2018.10.093 - Desteghe L, Raymaekers Z, Lutin M, Vijgen J, Dilling-Boer D, Koopman P, et al. Performance of handheld electrocardiogram devices to detect atrial fibrillation in a cardiology and geriatric ward setting. Europace 2017;19:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw025

1083. Nigolian A, Dayal N, Nigolian H, Stettler C, Burri H. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-lead ECGs obtained using a pocket-sized bipolar handheld event recorder. J Electrocardiol 2018;51:278–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.11.004 - Magnusson P, Lyren A, Mattsson G. Diagnostic yield of chest and thumb ECG after cryptogenic stroke, Transient ECG Assessment in Stroke Evaluation (TEASE): an observational trial. BMJ Open 2020;10:e037573. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037573

1085. Carnlöf C, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Jensen-Urstad M, Insulander P. Instant electrocardiogram feedback with a new digital technique reduces symptoms caused by palpitations and increases health-related quality of life (the RedHeart study). Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2021;20:402–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvaa031 - Haverkamp HT, Fosse SO, Schuster P. Accuracy and usability of single-lead ECG from smartphones—a clinical study. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2019;19:145–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipej.2019.02.006

1087. Attia ZI, Kapa S, Lopez-Jimenez F, McKie PM, Ladewig DJ, Satam G, et al. Screening for cardiac contractile dysfunction using an artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiogram. Nat Med 2019;25:70–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0240-2 - Bekker CL, Noordergraaf F, Teerenstra S, Pop G, van den Bemt BJF. Diagnostic accuracy of a single-lead portable ECG device for measuring QTc prolongation. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2020;25:e12683. https://doi.org/10.1111/anec.12683

- Kaleschke G, Hoffmann B, Drewitz I, Steinbeck G, Naebauer M, Goette A, et al. Prospective, multicentre validation of a simple, patient-operated electrocardiographic system for the detection of arrhythmias and electrocardiographic changes. Europace 2009;11:1362–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eup262

- Guan J, Wang A, Song W, Obore N, He P, Fan S, et al. Screening for arrhythmia with the new portable single-lead electrocardiographic device (SnapECG): an application study in community-based elderly population in Nanjing, China. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:133–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01512-4

- Svennberg E, Stridh M, Engdahl J, Al-Khalili F, Friberg L, Frykman V, et al. Safe automatic one-lead electro-cardiogram analysis in screening for atrial fibrillation. Europace 2017;19:1449–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw286

- Musat DL, Milstein N, Mittal S. Implantable loop recorders for cryptogenic stroke (plus real-world atrial fibrillation detection rate with implantable loop recorders). Card Electrophysiol Clin 2018;10:111–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccep.2017.11.011

- Sakhi R, Theuns D, Szili-Torok T, Yap SC. Insertable cardiac monitors: current indications and devices. Expert Rev Med Devices 2019;16:45–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/17434440.2018.1557046

- Tomson TT, Passman R. The reveal LINQ insertable cardiac monitor. Expert Rev Med Devices 2015;12:7–18. https://doi.org/10.1586/17434440.2014.953059

- Ciconte G, Saviano M, Giannelli L, Calovic Z, Baldi M, Ciaccio C, et al. Atrial fibrillation detection using a novel three-vector cardiac implantable monitor: the atrial fibrillation detect study. Europace 2017;19:1101–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw181

- Hindricks G, Pokushalov E, Urban L, Taborsky M, Kuck KH, Lebedev D, et al. Performance of a new leadless implantable cardiac monitor in detecting and quantifying atrial fibrillation: results of the XPECT trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010;3:141–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.109.877852

- Mittal S, Rogers J, Sarkar S, Koehler J, Warman EN, Tomson TT, et al. Real-world performance of an enhanced atrial fibrillation detection algorithm in an insertable cardiac monitor. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1624–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.05. 010

- Nölker G, Mayer J, Boldt LH, Seidl K VVAND, Massa T, Kollum M, et al. Performance of an implantable cardiac monitor to detect atrial fibrillation: results of the DETECT AF study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2016;27:1403–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.13089

- Sanders P, Pürerfellner H, Pokushalov E, Sarkar S, Di Bacco M, Maus B, et al.Performance of a new atrial fibrillation detection algorithm in a miniaturized insertable cardiac monitor: results from the reveal LINQ usability study. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1425–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.03.005

- Chan PH, Wong CK, Poh YC, Pun L, Leung WW, Wong YF, et al. Diagnostic performance of a smartphone-based photoplethysmographic application for atrial fibrillation screening in a primary care setting. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e003428. https:// doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003428

1101. Mc MD, Chong JW, Soni A, Saczynski JS, Esa N, Napolitano C, et al. PULSE-SMART: pulse-based arrhythmia discrimination using a novel smartphone application. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2016;27:51–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.12842 - Proesmans T, Mortelmans C, Van Haelst R, Verbrugge F, Vandervoort P, Vaes B.

Mobile phone-based use of the photoplethysmography technique to detect atrial fibrillation in primary care: diagnostic accuracy study of the FibriCheck app. JMIR

Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e12284. https://doi.org/10.2196/12284 - Rozen G, Vaid J, Hosseini SM, Kaadan MI, Rafael A, Roka A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a novel mobile phone application for the detection and monitoring of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2018;121:1187–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.01.035

- O’Sullivan JW, Grigg S, Crawford W, Turakhia MP, Perez M, Ingelsson E, et al. Accuracy of smartphone camera applications for detecting atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e202064. https://doi.org/10. 1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2064

1105. Koenig N, Seeck A, Eckstein J, Mainka A, Huebner T, Voss A, et al. Validation of a new heart rate measurement algorithm for fingertip recording of video signals with smartphones. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:631–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0212 - Krivoshei L, Weber S, Burkard T, Maseli A, Brasier N, Kühne M, et al. Smart detection of atrial fibrillation†. Europace 2017;19:753–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw125

1107. Wiesel J, Fitzig L, Herschman Y, Messineo FC. Detection of atrial fibrillation using a modified microlife blood pressure monitor. Am J Hypertens 2009;22:848–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2009.98 - Chen Y, Lei L, Wang JG. Atrial fibrillation screening during automated blood pressure measurement—comment on “diagnostic accuracy of new algorithm to detect atrial fibrillation in a home blood pressure monitor”. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2017;19: 1148–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13081

- Kane SA, Blake JR, McArdle FJ, Langley P, Sims AJ. Opportunistic detection of atrial fibrillation using blood pressure monitors: a systematic review. Open Heart 2016;3: e000362. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2015-000362

- Kario K. Evidence and perspectives on the 24-hour management of hypertension: hemodynamic biomarker-initiated ‘anticipation medicine’ for zero cardiovascular event. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2016;59:262–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2016.04.001

1111. Jaakkola J, Jaakkola S, Lahdenoja O, Hurnanen T, Koivisto T, Pänkäälä M, et al. Mobile phone detection of atrial fibrillation with mechanocardiography: the MODE-AF study (mobile phone detection of atrial fibrillation). Circulation 2018;137:1524–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032804

1112. Couderc JP, Kyal S, Mestha LK, Xu B, Peterson DR, Xia X, et al. Detection of atrial fibrillation using contactless facial video monitoring. Heart Rhythm 2015;12: 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.08.035 - Yan BP, Lai WHS, Chan CKY, Au ACK, Freedman B, Poh YC, et al. High-throughput, contact-free detection of atrial fibrillation from video with deep learning. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:105–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4004

- Yan BP, Lai WHS, Chan CKY, Chan SC, Chan LH, Lam KM, et al. Contact-free screening of atrial fibrillation by a smartphone using facial pulsatile photoplethysmographic signals. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e008585. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.008585

- Tsouri GR, Li Z. On the benefits of alternative color spaces for noncontact heart rate measurements using standard red-green-blue cameras. J Biomed Opt 2015;20:048002. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.20.4.048002

- Chan J, Rea T, Gollakota S, Sunshine JE. Contactless cardiac arrest detection using smart devices. NPJ Digit Med 2019;2:52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0128-7

- Guo Y, Wang H, Zhang H, Liu T, Liang Z, Xia Y, et al. Mobile photoplethysmographic technology to detect atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2365–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.019

1118. Lubitz SA, Faranesh AZ, Selvaggi C, Atlas SJ, McManus DD, Singer DE, et al. Detection of atrial fibrillation in a large population using wearable devices: the Fitbit heart study. Circulation 2022;146:1415–24. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060291

1119. Lopez Perales CR, Van Spall HGC, Maeda S, Jimenez A, Laţcu DG, Milman A, et al. Mobile health applications for the detection of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Europace 2021;23:11–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa139 - Gill S, Bunting KV, Sartini C, Cardoso VR, Ghoreishi N, Uh HW, et al. Smartphone detection of atrial fibrillation using photoplethysmography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2022;108:1600–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2021-320417

- Mant J, Fitzmaurice DA, Hobbs FD, Jowett S, Murray ET, Holder R, et al. Accuracy of diagnosing atrial fibrillation on electrocardiogram by primary care practitioners and interpretative diagnostic software: analysis of data from screening for atrial fibrillation in the elderly (SAFE) trial. BMJ 2007;335:380. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39227.551713.AE

- Halcox JPJ, Wareham K, Cardew A, Gilmore M, Barry JP, Phillips C, et al. Assessment of remote heart rhythm sampling using the AliveCor heart monitor to screen for atrial fibrillation: the REHEARSE-AF study. Circulation 2017;136:1784–94. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030583

1123. Duarte R, Stainthorpe A, Greenhalgh J, Richardson M, Nevitt S, Mahon J, et al. Lead-I ECG for detecting atrial fibrillation in patients with an irregular pulse using single time point testing: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2020;24:1–164. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta24030 - Mannhart D, Lischer M, Knecht S, du Fay de Lavallaz J, Strebel I, Serban T, et al. Clinical validation of 5 direct-to-consumer wearable smart devices to detect atrial fibrillation: BASEL wearable study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2023;9:232–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2022.09.011

1125. Paul Nordin A, Carnlöf C, Insulander P, Mohammad Ali A, Jensen-Urstad M, Saluveer O, et al. Validation of diagnostic accuracy of a handheld, smartphone-based rhythm recording device. Expert Rev Med Devices 2023;20:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/17434440.2023.2171290

1126. Gill SK, Barsky A, Guan X, Bunting KV, Karwath A, Tica O, et al. Consumer wearable devices to evaluate dynamic heart rate with digoxin versus beta-blockers: the RATE-AF randomised trial. Nat Med 2024;30:2030–2036. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03094-4.

1127. Kahwati LC, Asher GN, Kadro ZO, Keen S, Ali R, Coker-Schwimmer E, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA 2022;327:368–83. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.21811

1128. Strong K, Wald N, Miller A, Alwan A. Current concepts in screening for noncommunicable disease: World Health Organization Consultation Group Report on methodology of noncommunicable disease screening. J Med Screen 005;12:12–9. https://doi.org/10.1258/0969141053279086

1129. Whitfield R, Ascenção R, da Silva GL, Almeida AG, Pinto FJ, Caldeira D. Screening strategies for atrial fibrillation in the elderly population: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol 2023;112:705–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-022-02117-9 - Proietti M, Romiti GF, Vitolo M, Borgi M, Rocco AD, Farcomeni A, et al. Epidemiology of subclinical atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: a systematic review and meta-regression. Eur J Intern Med 2022;103:84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2022.06.023

1131. Healey JS, Alings M, Ha A, Leong-Sit P, Birnie DH, de Graaf JJ, et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation in older patients. Circulation 2017;136:1276–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028845

1132. Van Gelder IC, Healey JS, Crijns H, Wang J, Hohnloser SH, Gold MR, et al. Duration of device-detected subclinical atrial fibrillation and occurrence of stroke in ASSERT. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1339–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx042 - Kemp Gudmundsdottir K, Fredriksson T, Svennberg E, Al-Khalili F, Friberg L, Frykman V, et al. Stepwise mass screening for atrial fibrillation using N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide: the STROKESTOP II study. Europace 2020;22:24–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euz255

1134. Williams K, Modi RN, Dymond A, Hoare S, Powell A, Burt J, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial of screening for atrial fibrillation in people aged 70 years and over to reduce stroke: protocol for the pilot study for the SAFER trial. BMJ Open 2022;12: e065066. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065066 - Elbadawi A, Sedhom R, Gad M, Hamed M, Elwagdy A, Barakat AF, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation in the elderly: a network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Intern Med 2022;105:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2022.07.015

- McIntyre WF, Diederichsen SZ, Freedman B, Schnabel RB, Svennberg E, Healey JS. Screening for atrial fibrillation to prevent stroke: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Open 2022;2:oeac044. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjopen/oeac044

- Lyth J, Svennberg E, Bernfort L, Aronsson M, Frykman V, Al-Khalili F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of population screening for atrial fibrillation: the STROKESTOP study. Eur Heart J 2023;44:196–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac547

- Lubitz SA, Atlas SJ, Ashburner JM, Lipsanopoulos ATT, Borowsky LH, Guan W, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation in older adults at primary care visits: VITAL-AF randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2022;145:946–54. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057014

1139. Uittenbogaart SB, Verbiest-van Gurp N, Lucassen WAM, Winkens B, Nielen M, Erkens PMG, et al. Opportunistic screening versus usual care for detection of atrial fibrillation in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2020;370: m3208. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3208 - Kaasenbrood F, Hollander M, de Bruijn SH, Dolmans CP, Tieleman RG, Hoes AW, et al. Opportunistic screening versus usual care for diagnosing atrial fibrillation in general practice: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 2020;70:e427–33. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X708161

1141. Petryszyn P, Niewinski P, Staniak A, Piotrowski P, Well A, Well M, et al. Effectiveness of screening for atrial fibrillation and its determinants. A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14:e0213198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213198 - Wang Q, Richardson TG, Sanderson E, Tudball MJ, Ala-Korpela M, Davey Smith G, et al. A phenome-wide bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis of atrial fibrillation. Int J Epidemiol 2022;51:1153–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyac041

- Siddiqi HK, Vinayagamoorthy M, Gencer B, Ng C, Pester J, Cook NR, et al. Sex differences in atrial fibrillation risk: the VITAL rhythm study. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:1027–35. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2825

1144. Lu Z, Aribas E, Geurts S, Roeters van Lennep JE, Ikram MA, Bos MM, et al. Association between sex-specific risk factors and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation among women. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2229716. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29716 - Wong GR, Nalliah CJ, Lee G, Voskoboinik A, Chieng D, Prabhu S, et al. Sex-related differences in atrial remodeling in patients with atrial fibrillation: relationship to ablation outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2022;15:e009925. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.121.009925

1146. Mokgokong R, Schnabel R, Witt H, Miller R, Lee TC. Performance of an electronic health record-based predictive model to identify patients with atrial fibrillation across countries. PLoS One 2022;17:e0269867. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269867 - Schnabel RB, Witt H, Walker J, Ludwig M, Geelhoed B, Kossack N, et al. Machine learning-based identification of risk-factor signatures for undiagnosed atrial fibrillation in primary prevention and post-stroke in clinical practice. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2022;9:16–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcac013

- Himmelreich JCL, Veelers L, Lucassen WAM, Schnabel RB, Rienstra M, van Weert H, et al. Prediction models for atrial fibrillation applicable in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2020;22:684–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa005

1149. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e56–528. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659

1150. Allan V, Honarbakhsh S, Casas JP, Wallace J, Hunter R, Schilling R, et al. Are cardiovascular risk factors also associated with the incidence of atrial fibrillation? A systematic review and field synopsis of 23 factors in 32 population-based cohorts of 20 million participants. Thromb Haemost 2017;117:837–50. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH16-11-0825

1151. Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Van Gelder IC, Bax J, Hylek E, Kaab S, et al. Comprehensive risk reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation: emerging diagnostic and therapeutic options—a report from the 3rd Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus conference. Europace 2012;14:8–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eur241

1152. Lu Z, Tilly MJ, Geurts S, Aribas E, Roeters van Lennep J, de Groot NMS, et al. Sex-specific anthropometric and blood pressure trajectories and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022;29:1744–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwac083

1153. Giacomantonio NB, Bredin SS, Foulds HJ, Warburton DE. A systematic review of the health benefits of exercise rehabilitation in persons living with atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:483–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2012.07.003 - Andersen K, Farahmand B, Ahlbom A, Held C, Ljunghall S, Michaelsson K, et al. Risk of arrhythmias in 52 755 long-distance cross-country skiers: a cohort study. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3624–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht188

- Qureshi WT, Alirhayim Z, Blaha MJ, Juraschek SP, Keteyian SJ, Brawner CA, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: results from the Henry Ford exercise testing (FIT) project. Circulation 2015;131:1827–34. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014833

1156. Kwok CS, Anderson SG, Myint PK, Mamas MA, Loke YK. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177:467–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.104 - Abdulla J, Nielsen JR. Is the risk of atrial fibrillation higher in athletes than in the general population? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2009;11:1156–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eup197

1158. Cheng M, Hu Z, Lu X, Huang J, Gu D. Caffeine intake and atrial fibrillation incidence: dose response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Can J Cardiol 2014;30: 448–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2013.12.026 - Conen D, Chiuve SE, Everett BM, Zhang SM, Buring JE, Albert CM. Caffeine consumption and incident atrial fibrillation in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:509–14. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29627

1160. Shen J, Johnson VM, Sullivan LM, Jacques PF, Magnani JW, Lubitz SA, et al. Dietary factors and incident atrial fibrillation: the Framingham heart study. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93:261–6. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.001305 - Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, Larson MG, Beiser AS, McManus DD, et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham heart study: a cohort study. Lancet 2015;386:154–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61774-8

1162. Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Gardin JM, Smith VE, Rautaharju PM. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in elderly subjects (the cardiovascular health study). Am J Cardiol 1994;74:236–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(94)90363-8 - Lip GYH, Collet JP, de Caterina R, Fauchier L, Lane DA, Larsen TB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation associated with valvular heart disease: executive summary of a joint consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm

Association (EHRA) and European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, Endorsed by the ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease, Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), Heart Rhythm Society

(HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), South African Heart (SA Heart) Association and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulacion Cardiaca y Electrofisiologia (SOLEACE). Thromb Haemost 2017;117:2215–36. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH-17-10-0709 - Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham heart study. JAMA 1994;271:840–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1994.03510350050036

- Michniewicz E, Mlodawska E, Lopatowska P, Tomaszuk-Kazberuk A, Malyszko J. Patients with atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease—double trouble. Adv Med Sci 2018;63:30–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advms.2017.06.005

- Loomba RS, Buelow MW, Aggarwal S, Arora RR, Kovach J, Ginde S. Arrhythmias in adults with congenital heart disease: what are risk factors for specific arrhythmias? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2017;40:353–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/pace.12983

- Siland JE, Geelhoed B, Roselli C, Wang B, Lin HJ, Weiss S, et al. Resting heart rate and incident atrial fibrillation: a stratified Mendelian randomization in the AFGen consortium. PLoS One 2022;17:e0268768. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268768

- Geurts S, Tilly MJ, Arshi B, Stricker BHC, Kors JA, Deckers JW, et al. Heart rate variability and atrial fibrillation in the general population: a longitudinal and Mendelian randomization study. Clin Res Cardiol 2023;112:747–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-022-02072-5

1169. Aune D, Feng T, Schlesinger S, Janszky I, Norat T, Riboli E. Diabetes mellitus, blood glucose and the risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Diabetes Complications 2018;32:501–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.02.004 - Nakanishi K, Daimon M, Fujiu K, Iwama K, Yoshida Y, Hirose K, et al. Prevalence of glucose metabolism disorders and its association with left atrial remodelling before and after catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2023;25:euad119. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euad119

- Kim J, Kim D, Jang E, Kim D, You SC, Yu HT, et al. Associations of high-normal blood pressure and impaired fasting glucose with atrial fibrillation. Heart 2023;109:929–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2022-322094

1172. Lee SS, Ae Kong K, Kim D, Lim YM, Yang PS, Yi JE, et al. Clinical implication of an impaired fasting glucose and prehypertension related to new onset atrial fibrillation in a healthy Asian population without underlying disease: a ationwide cohort study in Korea. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2599–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx316 - Alonso A, Lopez FL, Matsushita K, Loehr LR, Agarwal SK, Chen LY, et al. Chronic kidney disease is associated with the incidence of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation 2011;123:2946–53. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.020982

1174. Bansal N, Zelnick LR, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, de Boer IH, Deo R, et al. eGFR and albuminuria in relation to risk of incident atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of the Jackson heart study, the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis, and the cardiovascular health study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:1386–98. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN. 01860217 - Asad Z, Abbas M, Javed I, Korantzopoulos P, Stavrakis S. Obesity is associated with incident atrial fibrillation independent of gender: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2018;29:725–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.13458

- Aune D, Sen A, Schlesinger S, Norat T, Janszky I, Romundstad P, et al. Body mass index, abdominal fatness, fat mass and the risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32: 181–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0232-4

- May AM, Blackwell T, Stone PH, Stone KL, Cawthon PM, Sauer WH, et al. Central sleep-disordered breathing predicts incident atrial fibrillation in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:783–91. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201508- 1523OC

- Tung P, Levitzky YS, Wang R, Weng J, Quan SF, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive and central sleep apnea and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in a community cohort of men and women. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e004500. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004500

1179. Desai R, Patel U, Singh S, Bhuva R, Fong HK, Nunna P, et al. The burden and impact of arrhythmia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from the national inpatient sample. Int J Cardiol 2019;281:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.074 - O’Neal WT, Efird JT, Qureshi WT, Yeboah J, Alonso A, Heckbert SR, et al. Coronary artery calcium progression and atrial fibrillation: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:e003786. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003786

- Chen LY, Leening MJ, Norby FL, Roetker NS, Hofman A, Franco OH, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness and the risk of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and the Rotterdam study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002907.

https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.002907 - Geurts S, Brunborg C, Papageorgiou G, Ikram MA, Kavousi M. Subclinical measures of peripheral atherosclerosis and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in the general population: the Rotterdam study. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;11:e023967. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.023967

1183. Cheng S, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, McCabe EL, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, et al. Long-term outcomes in individuals with prolonged PR interval or first-degree atrioventricular block. JAMA 2009;301:2571–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.888 - Alonso A, Jensen PN, Lopez FL, Chen LY, Psaty BM, Folsom AR, et al. Association of sick sinus syndrome with incident cardiovascular disease and mortality: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study and cardiovascular health study. PLoS One 2014; 9:e109662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109662

- Bodin A, Bisson A, Gaborit C, Herbert J, Clementy N, Babuty D, et al. Ischemic stroke in patients with sinus node disease, atrial fibrillation, and other cardiac conditions. Stroke 2020;51:1674–81. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029048

- Bunch TJ, May HT, Bair TL, Anderson JL, Crandall BG, Cutler MJ, et al. Long-term natural history of adult Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome patients treated with and without catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:1465–71. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003013

1187. Chang SH, Kuo CF, Chou IJ, See LC, Yu KH, Luo SF, et al. Association of a family history of atrial fibrillation with incidence and outcomes of atrial fibrillation: a population-based family cohort study. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:863–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1855

1188. Fox CS, Parise H, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Vasan RS, Wang TJ, et al. Parental atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in offspring. JAMA 2004;291:2851–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.23.2851 - Lubitz SA, Yin X, Fontes JD, Magnani JW, Rienstra M, Pai M, et al. Association between familial atrial fibrillation and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2010; 304:2263–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1690

- Zoller B, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. High familial risk of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter in multiplex families: a nationwide family study in Sweden. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e003384. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.112.003384

- Ko D, Benson MD, Ngo D, Yang Q, Larson MG, Wang TJ, et al. Proteomics profiling and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation: Framingham heart study. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e010976. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.010976

- Khera AV, Chaffin M, Aragam KG, Haas ME, Roselli C, Choi SH, et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat Genet 2018;50:1219–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0183-z

1193. Buckley BJR, Harrison SL, Gupta D, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Underhill P, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiomyopathy: prevalence and clinical outcomes from real-world data. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e021970. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.021970 - Chen M, Ding N, Mok Y, Mathews L, Hoogeveen RC, Ballantyne CM, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 and the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Clin Chem 2022;68:1084–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac096

- Chua W, Purmah Y, Cardoso VR, Gkoutos GV, Tull SP, Neculau G, et al. Data-driven discovery and validation of circulating blood-based biomarkers associated with prevalent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1268–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy815

- Brady PF, Chua W, Nehaj F, Connolly DL, Khashaba A, Purmah YJV, et al. Interactions between atrial fibrillation and natriuretic peptide in predicting heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular death. J Am Heart Assoc 2022;11:e022833. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.022833

- Werhahn SM, Becker C, Mende M, Haarmann H, Nolte K, Laufs U, et al. NT-proBNP as a marker for atrial fibrillation and heart failure in four observational outpatient trials. ESC Heart Fail 2022;9:100–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13703

- Geelhoed B, Börschel CS, Niiranen T, Palosaari T, Havulinna AS, Fouodo CJK, et al. Assessment of causality of natriuretic peptides and atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a Mendelian randomization study in the FINRISK cohort. Europace 2020;22:1463–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa158

1199. Toprak B, Brandt S, Brederecke J, Gianfagna F, Vishram-Nielsen JKK, Ojeda FM, et al. Exploring the incremental utility of circulating biomarkers for robust risk prediction of incident atrial fibrillation in European cohorts using regressions and modern machine learning methods. Europace 2023;25:812–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euac260 - Benz AP, Hijazi Z, Lindbäck J, Connolly SJ, Eikelboom JW, Oldgren J, et al. Biomarker-based risk prediction with the ABC-AF scores in patients with atrial fibrillation not receiving oral anticoagulation. Circulation 2021;143:1863–73. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.053100

- Monrad M, Sajadieh A, Christensen JS, Ketzel M, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Tjonneland A, et al. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: a cohort study. Environ Health Perspect 2017;125:422–7. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP392

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, Jensen PN, Piccini JP, Sinner MF, et al. Atrial fibrillation among medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J 2013;165:949–955.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020

- Svensson T, Kitlinski M, Engstrom G, Melander O. Psychological stress and risk of incident atrial fibrillation in men and women with known atrial fibrillation genetic risk scores. Sci Rep 2017;7:42613. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42613

- Eaker ED, Sullivan LM, Kelly-Hayes M, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Benjamin EJ. Anger and hostility predict the development of atrial fibrillation in men in the Framingham offspring study. Circulation 2004;109:1267–71. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000118535.15205.8F

- Chen LY, Bigger JT, Hickey KT, Chen H, Lopez-Jimenez C, Banerji MA, et al. Effect of intensive blood pressure lowering on incident atrial fibrillation and P-wave indices in the ACCORD blood pressure trial. Am J Hypertens 2016;29:1276–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpv172

1206. Soliman EZ, Rahman AF, Zhang ZM, Rodriguez CJ, Chang TI, Bates JT, et al. Effect of intensive blood pressure lowering on the risk of atrial fibrillation. Hypertension 2020; 75:1491–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14766 - Larstorp ACK, Stokke IM, Kjeldsen SE, Hecht Olsen M, Okin PM, Devereux RB, et al. Antihypertensive therapy prevents new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with isolated systolic hypertension: the LIFE study. Blood Press 2019;28:317–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08037051.2019.1633905

- Healey JS, Baranchuk A, Crystal E, Morillo CA, Garfinkle M, Yusuf S, et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1832–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.070

1209. Swedberg K, Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Shi H, et al. Eplerenone and atrial fibrillation in mild systolic heart failure: results from the EMPHASIS-HF (eplerenone in mild patients hospitalization and SurvIval study in heart failure) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1598–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.063

1210. Wang M, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Liu D, Mao S, Liang B. The effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitor in the incidence of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus/heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis 2022;14: 1620–37. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-22-550 - Yin Z, Zheng H, Guo Z. Effect of sodium-glucose co-transporter protein 2 inhibitors on arrhythmia in heart failure patients with or without type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9:902923. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.902923

1212. Tedrow UB, Conen D, Ridker PM, Cook NR, Koplan BA, Manson JE, et al. The longand short-term impact of elevated body mass index on the risk of new atrial fibrillation the WHS (Women’s Health Study). J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2319–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.029 - Chan YH, Chen SW, Chao TF, Kao YW, Huang CY, Chu PH. The impact of weight loss related to risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021; 20:93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-021-01285-8

- Mishima RS, Verdicchio CV, Noubiap JJ, Ariyaratnam JP, Gallagher C, Jones D, et al. Self-reported physical activity and atrial fibrillation risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm 2021;18:520–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.12.017

1215. Elliott AD, Linz D, Mishima R, Kadhim K, Gallagher C, Middeldorp ME, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of incident arrhythmias in 402 406 individuals: evidence from the UK Biobank cohort. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1479–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz897

1216. Jin MN, Yang PS, Song C, Yu HT, Kim TH, Uhm JS, et al. Physical activity and risk of atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study in general population. Sci Rep 2019;9: 13270. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49686-w - Khurshid S, Weng LC, Al-Alusi MA, Halford JL, Haimovich JS, Benjamin EJ, et al. Accelerometer-derived physical activity and risk of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2021;42:2472–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab250

- Tikkanen E, Gustafsson S, Ingelsson E. Associations of fitness, physical activity, strength, and genetic risk with cardiovascular disease: longitudinal analyses in the UK biobank study. Circulation 2018;137:2583–91. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032432

- Morseth B, Graff-Iversen S, Jacobsen BK, Jørgensen L, Nyrnes A, Thelle DS, et al. Physical activity, resting heart rate, and atrial fibrillation: the Tromsø study. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2307–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw059