TS. PHẠM HỮU VĂN

(…)

6.4. Nguy cơ đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ tồn đư mặc dù đã dùng thuốc chống đông

Mặc dù OAC làm giảm đáng kể nguy cơ đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ ở những bệnh nhân bị AF, nhưng vẫn còn nguy cơ tồn dư. [252,354] Một phần ba số bệnh nhân bị AF bị đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ đã được dùng thuốc chống đông, [355] với nguyên nhân không đồng nhất. [356] Điều này có thể bao gồm các cơ chế đột quỵ cạnh tranh không liên quan đến AF (như bệnh động mạch lớn và bệnh mạch máu nhỏ), không tuân thủ liệu pháp, liều thuốc chống đông thấp không phù hợp hoặc huyết khối tắc mạch mặc dù đã dùng thuốc chống đông đủ. [357] Đo nồng độ INR hoặc DOAC trong phòng thí nghiệm có thể góp phần phát hiện ra nguyên nhân dễ chấp nhận của đột quỵ. Bất kể tình trạng chống đông như thế nào, những bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ có nhiều khả năng có các yếu tố nguy cơ tim mạch hơn. [358] Nhiều bác sĩ lâm sàng đang điều trị cho những bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ mới mắc mặc dù đã dùng thuốc chống đông sẽ có xu hướng thay đổi phác đồ thuốc chống đông của họ. Mặc dù có thể có một số lợi thế khi chuyển từ VKA sang DOAC để bảo vệ chống lại đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ hoặc xuất huyết tái phát trong tương lai, lực lượng đặc nhiệm không khuyến cáo chuyển đổi thường xuyên từ DOAC này sang DOAC khác hoặc từ DOAC sang VKA vì hiệu quả chưa được chứng minh. [252,356,359]

Có thể có những lý do riêng để chuyển đổi, gồm các tương tác tiềm ẩn với thuốc mới; tuy nhiên, không có dữ liệu nhất quán giữa các quốc gia về việc tuân thủ hoặc hiệu quả khác nhau giữa các phương pháp dùng một lần và hai lần một ngày. [360,361] Bằng chứng mới nổi nhưng mang tính quan sát cho thấy việc chuyển đổi chỉ làm giảm hạn chế nguy cơ đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ tái phát. [252,356,359] Chiến lược thay thế là thêm liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu vào OAC có thể làm tăng nguy cơ chảy máu. [356,359] Bên cạnh việc chú ý kỹ lưỡng đến các yếu tố nguy cơ tiềm ẩn và các bệnh đi kèm, cách tiếp cận để quản lý bệnh nhân bị đột quỵ mặc dù dùng OAC vẫn là một thách thức riêng biệt

Bảng khuyến cáo 9 – Khuyến cáo về huyết khối thuyên tắc mặc dù đã dùng thuốc chống đông (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 9)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelb |

| Cần cân nhắc đánh giá chẩn đoán kỹ lưỡng ở những bệnh nhân dùng thuốc chống đông đường uống và bị đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ hoặc huyết khối thuyên tắc để ngăn ngừa các biến cố tái phát, gồm đánh giá các nguyên nhân không phải do tắc mạch tim, các yếu tố nguy cơ mạch máu, liều lượng và tuân thủ. [356,357] |

IIa |

B |

| Không khuyến cáo thêm thuốc chống tiểu cầu vào thuốc chống đông ở những bệnh nhân bị AF để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do tắc mạch tái phát. [356,359] |

III |

B |

| Không khuyến cáo chuyển từ DOAC này sang DOAC khác hoặc từ DOAC sang VKA mà không có chỉ định rõ ràng ở những bệnh nhân bị AF để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do tắc mạch tái phát. [252,356,359] |

III |

B |

AF: rung nhĩ; DOAC: thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp; VKA: thuốc kháng vitamin K.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

6.5. Bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái qua da

Bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái qua da (LAAO) là liệu pháp dựa trên thiết bị nhằm mục đích ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ ở những bệnh nhân bị AF.[362,363] Trong kỷ nguyên VKA, hai RCT đã so sánh warfarin với LAAO bằng cách sử dụng thiết bị Watchman. Kết quả gộp trong 5 năm đã chứng minh tỷ lệ tương tự của điểm cuối hợp thành (tử vong do tim mạch hoặc không rõ nguyên nhân, thuyên tắc hệ thống và đột quỵ) giữa nhóm LAAO và warfarin. Những người được phân ngẫu nhiên vào nhóm LAAO có tỷ lệ đột quỵ do xuất huyết và tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân thấp hơn đáng kể, nhưng cũng có tỷ lệ đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và thuyên tắc hệ thống tăng 71% không có ý nghĩa. [364] Với DOAC cho thấy tỷ lệ chảy máu lớn tương tự như aspirin, [242] warfarin ở nhóm chứng trong các thử nghiệm này không còn là tiêu chuẩn chăm sóc nữa và do đó vị trí của LAAO trong thực hành hiện tại vẫn chưa rõ ràng. Bộ phận bít tắc Amulet là một thiết bị LAAO thay thế không kém hơn thiết bị Watchman trong RCT về các biến cố an toàn (biến chứng liên quan đến thủ thuật, tử vong hoặc chảy máu lớn) và huyết khối tắc mạch. [365] Trong thử nghiệm PRAGUE-17, [402] bệnh nhân AF được phân ngẫu nhiên vào nhóm DOAC hoặc LAAO (Watchman hoặc Amulet), với sự không kém hơn được báo cáo đối với điểm cuối chính tổng hợp bao quát là đột quỵ, TIA, thuyên tắc hệ thống, tử vong do tim mạch, chảy máu lớn hoặc không lớn có liên quan đến lâm sàng và các biến chứng liên quan đến thủ thuật/thiết bị.[366,367] Các thử nghiệm lớn hơn [368,369] dự kiến sẽ cung cấp dữ liệu toàn diện hơn có thể bổ sung vào cơ sở bằng chứng hiện tại (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S10). Trong khi chờ các RCT tiếp theo (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng S4), những bệnh nhân có chống chỉ định với tất cả các lựa chọn OAC (bốn DOAC và VKA) có lý do chính đáng nhất để cấy ghép LAAO, mặc dù có nghịch lý là nhu cầu điều trị chống huyết khối sau thủ thuật khiến bệnh nhân có nguy cơ chảy máu có thể tương đương với DOAC. Các phê duyệt theo quy định dựa trên các giao thức RCT cho thấy cần phải dùng VKA cộng với aspirin trong 45 ngày sau khi cấy ghép, tiếp theo là 6 tháng DAPT ở những bệnh nhân không bị rò rỉ quanh thiết bị lớn, sau đó là aspirin liên tục (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Hình S2).[370–372] Tuy nhiên, thực hành trong thế giới thực lại khác biệt rõ rệt và cũng đa dạng. Việc sử dụng thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp ở liều đầy đủ hoặc liều giảm đã được đề xuất như một phương pháp điều trị thay thế cho warfarin. [373] Các nghiên cứu quan sát cũng đã hỗ trợ việc sử dụng liệu pháp chống tiểu cầu mà không làm tăng huyết khối hoặc đột quỵ liên quan đến thiết bị.[374–376] Trong một so sánh có khuynh hướng phù hợp giữa những bệnh nhân được điều trị OAC sớm hạn chế so với điều trị chống tiểu cầu sau khi cấy ghép Watchman, tỷ lệ biến cố huyết khối tắc mạch và biến chứng chảy máu là tương tự nhau.[377] Trong khi chờ dữ liệu RCT chắc chắn (NCT03445949, NCT03568890), [378] các quyết định có liên quan về điều trị chống huyết khối thường được đưa ra trên cơ sở cá nhân hóa.[379–381] Phòng ngừa đột quỵ tái phát, ngoài OAC, là một chỉ định tiềm năng khác cho LAAO. Cho đến nay chỉ có dữ liệu hạn chế từ các cơ quan đăng ký, [382] với các thử nghiệm đang diễn ra dự kiến sẽ cung cấp thêm thông tin chi tiết (NCT03642509, NCT05963698).

Việc cấy ghép thiết bị bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái có liên quan đến nguy cơ trong quá trình thủ thuật gồm đột quỵ, chảy máu nghiêm trọng, huyết khối liên quan đến thiết bị, tràn dịch màng ngoài tim, biến chứng mạch máu và tử vong.[362,383–385] Các sổ đăng ký tự nguyện ghi danh những bệnh nhân được coi là không đủ điều kiện để dùng OAC đã báo cáo nguy cơ thấp trong quá trình thủ thuật, [372,376,386,387] mặc dù các sổ đăng ký quốc gia báo cáo tỷ lệ biến cố bất lợi nghiêm trọng trong bệnh viện là 9,5% tại các trung tâm thực hiện 5–15 trường hợp LAAO mỗi năm và 5,6% thực hiện 32–211 trường hợp mỗi năm (P < 0.001). [388] Các sổ đăng ký có thiết bị thế hệ mới báo cáo tỷ lệ biến chứng thấp hơn so với dữ liệu RCT.[389,390] Huyết khối liên quan đến thiết bị xảy ra với tỷ lệ mắc là 1,7%–7,2% và có liên quan đến nguy cơ đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ cao hơn.[386,391–397] Việc phát hiện chúng có thể được ghi nhận muộn nhất là 1 năm sau khi cấy ghép ở một phần năm số bệnh nhân, do đó bắt buộc phải áp dụng phương pháp chụp ảnh ‘loại trừ’ muộn. [391] Tương tự như vậy, sàng lọc theo dõi rò rỉ quanh thiết bị là có liên quan, vì rò rỉ nhỏ (0–5 mm) có ở khoảng 25% và có liên quan đến các biến cố huyết khối tắc mạch và chảy máu cao hơn trong quá trình theo dõi 1 năm trong sổ đăng ký quan sát lớn của một thiết bị cụ thể. [398]

Bảng khuyến cáo 10 — Khuyến cáo về bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái qua da (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 10)

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | levelb |

| Có thể cân nhắc việc bít tắc LAA qua da ở những bệnh nhân bị AF và chống chỉ định điều trị chống đông máu dài hạn để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối thuyên tắc. [372,376,386,387] |

IIb

|

C

|

AF: rung nhĩ; LAA: tiểu nhĩ trái.

a Class khuyến cáo

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

6.6. Bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái bằng ngoại khoa

Việc bít tắc hoặc loại bỏ tiểu nhĩ trái (LAA) bằng ngoại khoa (LAA) có thể góp phần phòng ngừa đột quỵ ở những bệnh nhân bị AF phải phẫu thuật tim.[399,400] Nghiên cứu Bít tắc Tiểu nhĩ Trái (LAAOS III) đã phân ngẫu nhiên 4811 bệnh nhân bị AF để tiến hành hoặc không tiến hành LAAO tại thời điểm cho chỉ định khác nhau. Trong thời gian theo dõi trung bình là 3,8 năm, đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ hoặc thuyên tắc hệ thống xảy ra ở 114 bệnh nhân (4,8%) trong nhóm tắc nghẽn và 168 bệnh nhân (7,0%) trong nhóm đối chứng (HR, 0,67; 95% CI, 0,53–0,85; P = .001).[401] Thử nghiệm LAAOS III không so sánh việc tắc nghẽn phần phụ với thuốc chống đông (77% người tham gia tiếp tục dùng OAC), do đó, việc đóng LAA bằng phẫu thuật nên được xem xét như một liệu pháp bổ sung để phòng ngừa huyết khối thuyên tắc ngoài việc chống đông ở những bệnh nhân bị AF.

Không có dữ liệu RCT nào cho thấy tác dụng có lợi đối với đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ hoặc thuyên tắc hệ thống ở những bệnh nhân AF trải qua LAAO trong quá trình triệt phá AF nội soi hoặc kết hợp. Một phân tích tổng hợp dữ liệu RCT và quan sát cho thấy không có sự khác biệt trong việc phòng ngừa đột quỵ hoặc tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân khi so sánh việc kẹp LAA trong quá trình triệt phá AF qua nội soi ngực với LAAO qua da và triệt phá qua catheter. [402] Trong khi nhóm LAAO qua da / triệt phá qua catheter cho thấy tỷ lệ thành công cấp thời cao hơn, thì nó cũng liên quan đến nguy cơ xuất huyết cao hơn trong giai đoạn quanh phẫu thuật. Trong một nghiên cứu quan sát đánh giá [222] bệnh nhân AF trải qua đóng LAA bằng thiết bị kẹp như một phần của quá trình triệt phá AF nội soi hoặc kết hợp, việc đóng hoàn toàn đã đạt được ở 95% bệnh nhân. [403] Không có biến chứng trong khi phẫu thuật và không có điểm cuối kết hợp là đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ, đột quỵ xuất huyết hoặc TIA là 99,1% trong [369] năm bệnh nhân theo dõi. Các thử nghiệm đánh giá tác dụng có lợi của việc đóng LAA phẫu thuật ở những bệnh nhân phẫu thuật tim nhưng không có tiền sử AF đang được tiến hành (NCT03724318, NCT02701062). [404]

Có một lợi thế tiềm tàng đối với việc đóng LAA ngoài màng tim độc lập so với đóng LAA qua da ở những bệnh nhân có chống chỉ định với OAC, vì không cần dùng thuốc chống đông sau thủ thuật sau khi đóng LAA ngoài màng tim. Dữ liệu quan sát cho thấy việc đóng LAA độc lập bằng kẹp ngoài màng tim là khả thi và an toàn. [405] Một phương pháp tiếp cận của nhóm đa chuyên khoa có thể tạo điều kiện thuận lợi cho việc lựa chọn giữa đóng LAA ngoài màng tim hoặc qua da ở những bệnh nhân như vậy. [406] Phần lớn dữ liệu và kinh nghiệm về an toàn trong việc đóng LAA ngoài màng tim bắt nguồn từ một thiết bị kẹp duy nhất (AtriClip) [403,407,408] (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S11).

Bảng khuyến cáo 11 — Bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái bằng ngoại khoa (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 11)

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | levelb |

| Bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái bằng ngoại khoa được khuyến cáo là phương pháp bổ sung cho thuốc chống đông đường uống ở những bệnh nhân AF đang phẫu thuật tim để

ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối tắc mạch. [400,401,408–412] |

I |

B |

| Nên cân nhắc bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái bằng ngoại khoa như phương pháp bổ sung cho thuốc chống đông đường uống ở những bệnh nhân AF đang cắt đốt AF nội soi hoặc kết hợp để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ do thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối thuyên tắc. [402,403] |

IIa |

C |

| Bít tắc tiểu nhĩ trái bằng nội soi ngoại khoa độc lập có thể được xem xét ở các bệnh nhân AF và chống chỉ định với điều trị chống đông dài hạn để ngăn ngừa đột quỵ thiếu máu cục bộ và huyết khối thuyên tắc. [399,405,406,413] |

IIb |

C |

AF: rung nhĩ.

a Class khuyến cáo

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

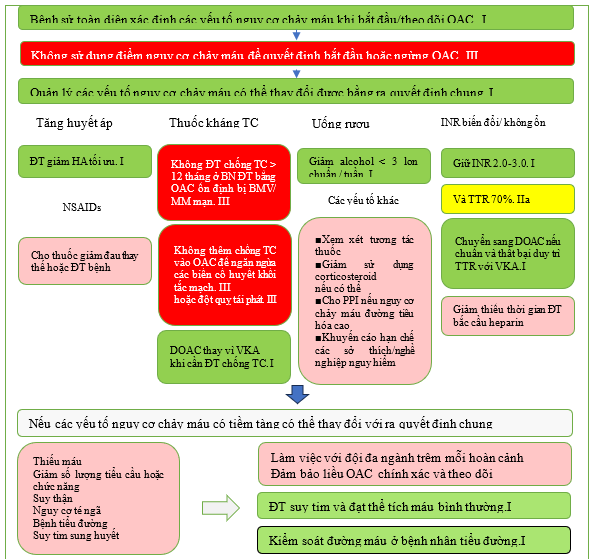

6.7. Nguy cơ chảy máu

6.7.1. Đánh giá nguy cơ chảy máu

Khi khởi đầu điều trị chống huyết khối, các yếu tố nguy cơ chảy máu có thể thay đổi nên được điều chỉnh để cải thiện tính an toàn (Hình 10). [414–418] Điều này gồm kiểm soát chặt chẽ tình trạng tăng huyết áp, tư vấn giảm lượng uống alcohol quá mức, tránh dùng thuốc chống tiểu cầu hoặc thuốc chống viêm không cần thiết và chú ý đến liệu pháp OAC (tuân thủ, kiểm soát TTR nếu đang dùng VKA và xem xét các loại thuốc tương tác). Các bác sĩ lâm sàng nên cân nhắc sự cân bằng giữa đột quỵ và nguy cơ chảy máu—vì các yếu tố của cả hai đều thay đổi và chồng chéo, nên chúng cần được đánh giá lại tại mỗi lần đánh giá tùy thuộc vào từng bệnh nhân. [419–421] Các yếu tố nguy cơ chảy máu hiếm khi là lý do để ngừng hoặc tạm dừng OAC ở những bệnh nhân đủ điều kiện, vì nguy cơ đột quỵ nếu không dùng thuốc chống đông thường lớn hơn nguy cơ chảy máu nghiêm trọng. [422,423] Bệnh nhân có các yếu tố nguy cơ không thể thay đổi nên được xem xét thường xuyên hơn và khi thích hợp, nên thiết lập phương pháp tiếp cận theo nhóm đa chuyên khoa để hướng dẫn việc quản lý.

Một số điểm nguy cơ chảy máu đã được phát triển để tính đến nhiều yếu tố lâm sàng (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng S5 và Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S12 và S13).[424] Các đánh giá có hệ thống và nghiên cứu xác nhận trong các nhóm bên ngoài đã cho thấy kết quả tương phản và chỉ có khả năng dự đoán khiêm tốn. [244,425–434] Lực lượng đặc nhiệm không khuyến cáo một điểm nguy cơ chảy máu cụ thể do tính không chắc chắn về độ chính xác và những tác động bất lợi tiềm ẩn của việc không cung cấp OAC phù hợp cho những người có nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch. Có rất ít chống chỉ định tuyệt đối đối với OAC (đặc biệt là liệu pháp DOAC). Trong khi khối u nội sọ nguyên phát [435] hoặc chảy máu nội sọ liên quan đến bệnh lý mạch máu não do lắng đọng amyloid [436] là những ví dụ mà OAC nên tránh, thì nhiều chống chỉ định khác chỉ là tương đối hoặc tạm thời. Ví dụ, DOAC thường có thể được bắt đầu hoặc bắt đầu lại một cách an toàn sau khi chảy máu cấp tính đã ngừng, miễn là nguồn gốc đã được điều tra và xử lý đầy đủ. Việc kê đơn đồng thời thuốc ức chế bơm proton là phổ biến trong thực hành lâm sàng đối với những bệnh nhân đang dùng OAC có nguy cơ cao bị chảy máu đường tiêu hóa. Tuy nhiên, cơ sở bằng chứng còn hạn chế và không cụ thể ở những bệnh nhân bị AF. Trong khi các nghiên cứu quan sát đã chỉ ra lợi ích tiềm năng từ thuốc ức chế bơm proton, [437] một RCT lớn ở những bệnh nhân đang dùng thuốc chống đông liều thấp và/hoặc aspirin để điều trị bệnh tim mạch ổn định đã phát hiện ra rằng pantoprazole không có tác động đáng kể đến các biến cố chảy máu đường tiêu hóa trên so với giả dược (HR, 0,88; 95% CI, 0,67–1,15). [438] Do đó, việc sử dụng thuốc bảo vệ dạ dày nên được cá nhân hóa cho từng bệnh nhân theo tổng thể nguy cơ chảy máu được nhận ra từ họ.

Bảng khuyến cáo 12 — Khuyến cáo để đánh giá nguy cơ chảy máu (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 12)

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | levelb |

| Đánh giá và điều chỉnh các yếu tố nguy cơ chảy máu có thể thay đổi được khuyến cáo ở tất cả bệnh nhân đủ điều kiện dùng thuốc chống đông đường uống, như một phần của quá trình ra quyết định chung để đảm bảo an toàn và ngăn ngừa chảy máu. [439–444] |

I |

B |

| Không khuyến cáo sử dụng điểm số nguy cơ chảy máu để quyết định khởi đầu hay ngừng thuốc chống đông đường uống ở bệnh nhân AF để tránh sử dụng thuốc chống đông không đủ liều. [431,445,446] |

III |

B |

AF: rung nhĩ.

a Class khuyến cáo

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

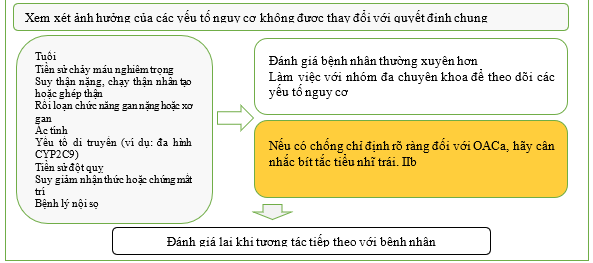

6.7.2. Quản lý chảy máu khi điều trị bằng thuốc chống đông

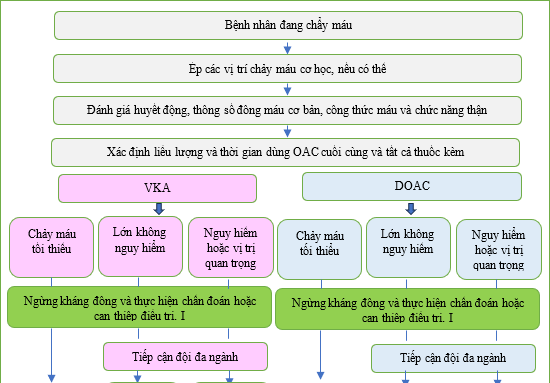

Quản lý chảy máu chung ở những bệnh nhân dùng OAC được nêu trong Hình 11. Quản lý theo nguyên nhân nằm ngoài phạm vi của các hướng dẫn này và sẽ phụ thuộc vào hoàn cảnh cá nhân của bệnh nhân và môi trường chăm sóc sức khỏe. [447] Đánh giá bệnh nhân đang chảy máu hoạt động nên bao gồm xác nhận vị trí chảy máu, mức độ chảy máu, loại/liều/thời điểm dùng thuốc chống đông gần nhất, sử dụng đồng thời các thuốc chống huyết khối khác và các yếu tố khác ảnh hưởng đến nguy cơ chảy máu (chức năng thận, số lượng tiểu cầu và thuốc như thuốc chống viêm không steroid). Xét nghiệm INR và thông tin về kết quả gần đây rất có giá trị đối với bệnh nhân dùng VKA. Các xét nghiệm đông máu cụ thể

cho DOAC gồm thời gian thrombin được pha loãng, thời gian đông máu ecarin, xét nghiệm sinh sắc tố ecarin cho dabigatran và xét nghiệm kháng yếu tố Xa sinh sắc tố cho rivaroxaban, apixaban và edoxaban. [447–449] Các can thiệp chẩn đoán và điều trị để xác định và xử lý nguyên nhân gây chảy máu (ví dụ như nội soi dạ dày) nên được thực hiện kịp thời.

Trong trường hợp chảy máu nhẹ, việc ngừng tạm thời OAC trong khi xử lý nguyên nhân thường là đủ, lưu ý việc giảm tác dụng chống đông máu phụ thuộc vào mức INR đối với VKA hoặc thời gian bán hủy của DOAC cụ thể.

Đối với các biến cố chảy máu lớn ở những bệnh nhân dùng VKA, việc truyền huyết tương đông lạnh tươi giúp phục hồi quá trình đông máu nhanh hơn vitamin K, nhưng các chất cô đặc phức hợp prothrombin đạt được quá trình đông máu nhanh hơn với ít biến chứng hơn và do đó được ưu tiên hơn để cầm máu. [450] Ở những bệnh nhân được điều trị bằng DOAC, trong đó liều DOAC cuối cùng được dùng trong vòng 2–4 giờ, việc dùng than hoạt tính và/hoặc rửa dạ dày có thể làm giảm phơi nhiễm thêm.

Nếu bệnh nhân đang dùng dabigatran, idarucizumab có thể đảo ngược hoàn toàn tác dụng chống đông máu của thuốc và giúp cầm máu trong vòng 2–4 giờ trong trường hợp chảy máu không kiểm soát được. [451] Thẩm phân cũng có thể có hiệu quả trong việc giảm nồng độ dabigatran. Andexanet alfa nhanh chóng đảo ngược hoạt động của chất ức chế yếu tố Xa (apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S14). Một RCT nhãn mở so sánh andexanet alfa với cách chăm sóc thông thường ở những bệnh nhân bị ICH cấp tính trong vòng 6 giờ kể từ khi khởi phát triệu chứng đã bị dừng sớm do kiểm soát tốt hơn tình trạng

chảy máu sau khi 450 bệnh nhân được phân bổ ngẫu nhiên. [452] Vì thuốc giải độc đặc hiệu DOAC vẫn chưa có sẵn ở tất cả các cơ sở, nên các chất cô đặc phức hợp prothrombin thường được sử dụng trong các trường hợp chảy máu nghiêm trọng khi dùng thuốc ức chế yếu tố Xa, với bằng chứng chỉ giới hạn ở các nghiên cứu quan sát. [453]

Do việc kiểm soát chảy máu ở những bệnh nhân dùng OAC rất phức tạp, nên mỗi cơ sở nên xây dựng các chính sách cụ thể liên quan đến một nhóm đa chuyên khoa bao gồm bác sĩ tim mạch, bác sĩ huyết học, bác sĩ cấp cứu/chuyên gia chăm sóc tích cực, bác sĩ phẫu thuật và những người khác. Điều quan trọng nữa là phải giáo dục bệnh nhân dùng thuốc chống đông máu về các dấu hiệu và triệu chứng của các biến cố chảy máu và thông báo cho bác sĩ chăm sóc sức khỏe của họ khi các biến cố như vậy xảy ra. [335]

Quyết định khôi phục OAC sẽ được xác định do mức độ nghiêm trọng, nguyên nhân và cách kiểm soát chảy máu sau đó, tốt nhất là do một nhóm đa chuyên khoa thực hiện và theo dõi chặt chẽ. Không tái lập OAC sau khi chảy máu làm tăng đáng kể nguy cơ nhồi máu cơ tim, đột quỵ và tử vong. [454] Tuy nhiên, nếu nguyên nhân gây chảy máu nghiêm trọng hoặc đe dọa tính mạng không thể được điều trị hoặc đảo ngược, nguy cơ chảy máu liên tục có thể lớn hơn lợi ích của biện pháp bảo vệ huyết khối. [335]

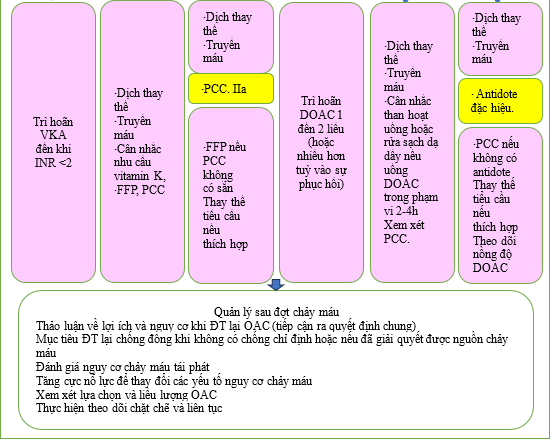

Bảng khuyến cáo 13 — Khuyến cáo về việc quản lý chảy máu ở bệnh nhân dùng thuốc chống đông (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 13)

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | levelb |

| Nên ngừng thuốc chống đông và thực hiện các can thiệp chẩn đoán hoặc điều trị ở những bệnh nhân AF đang chảy máu cho đến khi xác định và giải quyết được nguyên nhân gây chảy máu. |

I |

C |

| Cần cân nhắc sử dụng phức hợp prothrombin cô đặc (PCC) ở những bệnh nhân AF đang dùng VKA bị chảy máu đe dọa tính mạng hoặc chảy máu vào vị trí quan trọng để đảo ngược tác dụng chống huyết khối.[450] |

IIa |

C |

| Cần cân nhắc sử dụng thuốc giải độc (antidote) đặc hiệu ở những bệnh nhân AF đang dùng DOAC bị chảy máu đe dọa tính mạng hoặc chảy máu vào vị trí quan trọng để đảo ngược tác dụng chống huyết khối.[451,455,456] |

IIa |

B |

AF: rung nhĩ.DOAC: kháng đông tác dụng trực tiếp uống. VKA: kháng vitamine K.

a Class khuyến cáo

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

7. [R] Giảm triệu chứng bằng cách kiểm soát nhịp và tần số

Hầu hết bệnh nhân được chẩn đoán AF sẽ cần các các điều trị và/hoặc can thiệp để kiểm soát nhịp tim, trở lại nhịp xoang hoặc duy trì nhịp xoang để hạn chế các triệu chứng hoặc cải thiện kết quả. Mặc dù khái niệm lựa chọn giữa kiểm soát nhịp và tần số thường được thảo luận, nhưng trên thực tế, hầu hết bệnh nhân cần một phương pháp kết hợp, phương pháp này nên được đánh giá lại một cách một cách sáng suốt trong quá trình theo dõi. Trong phương pháp tiếp cận quản lý chung và lấy bệnh nhân làm trung tâm, kiểm soát nhịp tim nên được cân nhắc ở tất cả các bệnh nhân AF phù hợp, với thảo luận rõ ràng về lợi ích và nguy cơ.

7.1. Quản lý tần số tim ở bệnh nhân AF

Hạn chế nhịp tim nhanh là một phần không thể thiếu trong quá trình quản lý AF và thường đủ để cải thiện các triệu chứng liên quan đến AF. Kiểm soát tần số được chỉ định là liệu pháp ban đầu trong trường hợp cấp tính, kết hợp với các liệu pháp kiểm soát nhịp hoặc là chiến lược điều trị duy nhất để kiểm soát tần số tim và giảm các triệu chứng. Có rất ít bằng chứng để đưa ra loại và cường độ điều trị kiểm soát tần số tốt nhất. [457] Phương pháp kiểm soát tần số tim được trình bày trong Hình 7 có thể được sử dụng cho tất cả các loại AF, bao gồm AF kịch phát, dai dẳng và vĩnh viễn..

Hình 10 Nguy cơ chảy máu liên quan OAC được sửa đổi. DOAC: chống đông trực tiếp uống; INR, tỷ lệ chuẩn hóa quốc tế; NSAID, thuốc chống viêm không steroid; TTR: thời gian phạm vi điều trị; VKA, thuốc kháng vitamin K. ĐT: điều trị. TC: tiểu cầu.

Hình 11: Quản lý chảy máu liên quan đến OAC ở bệnh nhân AF. DOAC: chống đông trực tiếp uống; FFP, huyết tương tươi đông lạnh; PCC, phức hợp prothrombin cô đặc.

Bảng khuyến cáo 14 — Khuyến cáo về kiểm soát tần số tim ở bệnh nhân AF (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 14)

| Khuyến cáo | Classa | levelb |

| Liệu pháp kiểm soát tần số được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân AF, như liệu pháp khởi đầu trong bối cảnh cấp tính, một liệu pháp bổ sung cho liệu pháp kiểm soát nhịp hoặc như một chiến lược điều trị duy nhất để kiểm soát tần số tim và giảm các triệu chứng. [458–460] |

I |

B |

| Thuốc chẹn beta, diltiazem, verapamil hoặc digoxin được khuyến cáo là thuốc lựa chọn đầu tiên ở những bệnh nhân AF và LVEF >40% để kiểm soát tần số tim và giảm các triệu chứng.[48,461,462] |

I |

B |

| Thuốc chẹn beta và/hoặc digoxin được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân AF và LVEF ≤40% để kiểm soát nhịp tim và giảm các triệu chứng [40,185,463–465] |

I |

B |

| Điều trị kiểm soát tần số phối hợp nên được xem xét nếu một loại thuốc duy nhất không kiểm soát được các triệu chứng hoặc tần số tim ở những bệnh nhân bị AF, với điều kiện có thể tránh được nhịp tim chậm, để kiểm soát tần số tim và giảm các triệu chứng. |

IIa |

C |

| Kiểm soát tần số không chặt chẽ (lenient) với tần số tim lúc nghỉ < 110 nhịp/phút nên được coi là mục tiêu ban đầu cho bệnh nhân AF, với mục tiêu kiểm soát chặt chẽ hơn dành cho những bệnh nhân có các triệu chứng liên quan đến AF liên tục (tần số tim lúc ghỉ < 80 nhịp / phút). [459,460,466] |

IIa |

B |

| Triệt phá nút nhĩ thất phối hợp với cấy máy tạo nhịp nên được xem xét ở các bệnh nhân không đáp ứng hoặc không đủ điều kiện để điều trị kiểm soát tần số tích cực và kiểm soát nhịp để kiểm soát tần số và giảm triệu chứng. [467–469] |

IIa |

B |

| Triệt phá nút nhĩ thất được phối hợp với điều trị tái đồng bộ tim nên được xem xét ở các bệnh nhân có triệu chứng nặng với AF mạn tính và ít nhân một lần nhập viện do HF để giảm triệu chứng, hạn chế thể lực, nhập viện do HF tài phát và tử suất. [470,471] |

IIa |

B |

| Có thể cân nhắc dùng amiodarone, digoxin, esmolol hoặc landiolol tiêm tĩnh mạch ở những bệnh nhân AF có tình trạng huyết động không ổn định hoặc LVEF giảm nghiêm trọng để kiểm soát tần số tim cấp thời. [472,473] |

IIb |

B |

AF: rung nhĩ. AF; HF: suy tim; LVEF: phân suất tống máu thất trái.

a Class khuyến cáo

b Mức độ bằng chứng.

7.1.1. Chỉ định và nhịp tim mục tiêu

Nhịp tim mục tiêu tối ưu ở bệnh nhân AF phụ thuộc vào bối cảnh, gánh nặng triệu chứng, tình trạng suy tim và việc kiểm soát tần số có kết hợp với chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp hay không. Trong RCT RACE II (Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation: Hiệu quả kiểm soát tần số trong rung nhĩ vĩnh viễn) của bệnh nhân bị AF vĩnh viễn, kiểm soát tần số tim không chặt chẽ (lenient) (nhịp tim mục tiêu <110/phút) không kém hơn phương pháp tiếp cận chặt chẽ (<80 /phút khi nghỉ ngơi; <110 b.p.m. khi gắng sức; Holter để đảm bảo an toàn) đối với một hỗn hợp các biến cố lâm sàng, phân loại NYHA hoặc nhập viện.[186,459] Kết quả tương tự đã được tìm thấy trong một phân tích kết hợp sau thử nghiệm từ các nghiên cứu AFFIRM (Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management: Điều tra theo dõi rung nhĩ về quản lý nhịp) và RACE (Rate Control versus Electrical cardioversion: Kiểm soát tần số so với chuyển nhịp). [474] Do đó, kiểm soát tần số không chặt chẽ là một cách tiếp cận ban đầu có thể chấp nhận được, trừ khi có các triệu chứng đang diễn ra hoặc nghi ngờ bệnh cơ tim do nhịp tim nhanh, trong đó có thể chỉ định các mục tiêu chặt chẽ hơn.

7.1.2. Kiểm soát nhịp tim trong bối cảnh cấp thời

Trong bối cảnh cấp, bác sĩ nên luôn đánh giá và quản lý các nguyên nhân tiềm ẩn gây ra AF trước khi hoặc song song với việc thiết lập kiểm soát nhịp tim và/hoặc tần số cấp thời. Các nguyên nhân này bao gồm điều trị nhiễm trùng huyết, giải quyết tình trạng quá tải dịch hoặc kiểm soát sốc tim. Việc lựa chọn thuốc (Bảng 12) sẽ phụ thuộc vào đặc điểm của bệnh nhân, tình trạng suy tim và LVEF, cũng như hồ sơ huyết động (Hình 7). Nhìn chung, để kiểm soát tần số cấp thời, thuốc chẹn beta (cho tất cả LVEF) và diltiazem/verapamil (cho LVEF >40%) được ưu tiên hơn digoxin vì chúng có tác dụng khởi phát nhanh hơn và tác dụng phụ thuộc vào liều dùng.[462,475,476] Thuốc chẹn thụ thể beta-1 chọn lọc hơn có hiệu quả và hồ sơ an toàn tốt hơn thuốc chẹn beta không chọn lọc.[477] Có thể cần phải kết hợp liệu pháp với digoxin trong các trường hợp cấp (nên tránh kết hợp thuốc chẹn beta với diltiazem/verapamil trừ khi trong các trường hợp được theo dõi chặt chẽ).[177,478] Ở những bệnh nhân được chọn không ổn định về huyết động hoặc suy giảm LVEF nghiêm trọng, có thể sử dụng amiodarone, landiolol hoặc digoxin tĩnh mạch.[472,473,479]

7.1.3. Kiểm soát tần số tim dài hạn

Kiểm soát tần số bằng thuốc có thể đạt được bằng thuốc chẹn beta, diltiazem, verapamil, digoxin hoặc điều trị kết hợp (Bảng 12) (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S15).[480]

Việc lựa chọn thuốc kiểm soát tần số phụ thuộc vào các triệu chứng, bệnh đi kèm và khả năng xảy ra tác dụng phụ và tương tác. Chỉ nên cân nhắc liệu pháp kết hợp các loại thuốc kiểm soát tần số khác nhau khi cần thiết để đạt được tần số mục tiêu và nên theo dõi cẩn thận để tránh nhịp tim chậm. Chỉ nên kết hợp thuốc chẹn beta với verapamil hoặc diltiazem trong chăm sóc thứ hai với việc theo dõi thường xuyên nhịp tim bằng ECG 24 giờ để kiểm tra nhịp tim chậm. [459] Một số thuốc chống loạn nhịp (AAD) cũng có đặc tính giới hạn tần số (ví dụ: amiodarone, sotalol), nhưng nhìn chung chúng chỉ nên được sử dụng để kiểm soát nhịp tim. Không nên dùng dronedarone để kiểm soát tần số vì nó làm tăng tỷ lệ suy tim, đột quỵ và tử vong do tim mạch ở bệnh nhân AF vĩnh viễn.[481]

Thuốc chẹn beta, đặc biệt là thuốc đối kháng thụ thể adrenoreceptor chọn lọc beta-1, thường là thuốc kiểm soát tần số tim hàng đầu chủ yếu dựa trên tác dụng cấp thời của chúng đối với tần số tim và các tác dụng có lợi đã được chứng minh ở những bệnh nhân bị HFrEF mạn tính. Tuy nhiên, lợi ích tiên lượng của thuốc chẹn beta ở những bệnh nhân HFrEF có nhịp xoang có thể không có ở những bệnh nhân bị AF.[133,482]

Verapamil và diltiazem là thuốc chẹn kênh canxi không phải dihydropyridine. Chúng kiểm soát tần số tim [461] và có hồ sơ tác dụng phụ khác nhau, khiến verapamil hoặc diltiazem hữu ích cho những người gặp tác dụng phụ từ thuốc chẹn beta.[483] Trong một RCT chéo gồm 60 bệnh nhân, verapamil và diltiazem không dẫn đến tình trạng giảm khả năng gắng sức giống như thuốc chẹn beta và có tác động có lợi lên BNP.[480]

Digoxin và digitoxin là glycosid tim ức chế adenosine triphosphatase natri-kali và tăng trương lực phó giao cảm. Trong RCT, không có mối liên quan nào giữa việc sử dụng digoxin và bất kỳ sự gia tăng nào về tỷ lệ tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân. [185,484] Liều digoxin thấp hơn có thể liên quan đến tiên lượng tốt hơn.[185] Nồng độ digoxin trong huyết thanh có thể được theo dõi để tránh độc tính, [485] đặc biệt là ở những bệnh nhân có nguy cơ cao hơn do tuổi cao hơn, rối loạn chức năng thận hoặc sử dụng thuốc có tương tác. Trong RATE-AF (RAte control Therapy Evaluation in permanent Atrial Fibrillation: Đánh giá liệu pháp kiểm soát tần số trong rung nhĩ vĩnh viễn), một thử nghiệm ở những bệnh nhân bị AF vĩnh viễn có triệu chứng, không có sự khác biệt giữa digoxin liều thấp và bisoprolol đối với kết quả chất lượng cuộc sống do bệnh nhân báo cáo sau 6 tháng. Tuy nhiên, những người được phân ngẫu nhiên dùng digoxin cho thấy ít tác dụng phụ hơn, cải thiện nhiều hơn về điểm mEHRA và NYHA và giảm BNP.[48] Hai RCT đang được tiến hành đang giải quyết vấn đề sử dụng digoxin và digitoxin ở những bệnh nhân mắc HFrEF có và không có AF (EudraCT- 2013-005326-38, NCT03783429).[486]

Do hồ sơ tác dụng phụ ngoài tim rộng, amiodarone được dành riêng làm lựa chọn cuối cùng khi nhịp tim không thể kiểm soát được ngay cả với liệu pháp kết hợp dung nạp tối đa, hoặc ở những bệnh nhân không đủ điều kiện để triệt phá nút nhĩ thất và tạo nhịp. Nhiều tác dụng phụ từ amiodarone có mối quan hệ trực tiếp với liều tích lũy, hạn chế giá trị lâu dài của amiodarone đối với việc kiểm soát tần số tim. [487]

Bảng 12 – Các thuốc cho kiểm soát tần số trong AF

| Thuốca | Sử dụng đường tĩnh mạch | Phạm vi thường cho liều uống duy trì | Chống chỉ định |

| Beta blockerb | |||

| Metoprlol succinate | 2.5–5 mg bolus trong 2 phút; đến tổng liều tối đa 15 mg | 25–100 mg hai lần ngày

|

Trong trường hợp hen phế quản, các beta blocker nên được tránh

Chống chỉ đị phối hợp trong suy tim cấp và co thắt phế quản nặng. |

| Metoprolol XL (succinate) |

N/A

|

50–200 mg một lần ngày

|

|

| Bisoprolol | N/A

|

1.25–20 mg một lần ngày

|

|

| Atenololc | N/A

|

25–100 mg một lần ngày

|

|

| Esmolol | 500 µg/kg i.v. bolus qua 1 phút; tiếp sau bằng 50–300 µg / kg /phút | N/A

|

|

| Landiolol | 00 µg/kg i.v. bolus qua 1 phút; tiếp theo bằng 10–40 µg/kg/phút |

N/A

|

|

| Nebivolol | N/A | 2.5–10 mg một lần ngày | |

| Carvedilol | N/A | 3.125–50 mg hai lần ngày | |

| Các chẹn kênh can xi non hydropyridine. | |||

| Verapamil | 2.5–10 mg i.v. bolus trong 5 phút | 40 mg hai lần ngày đến 480 mg (ngoại trừ thải tiết chậm) một lần ngày | Chống chỉ định nều LVEF ≤40%. Các liều tương ứng trong suy gan và suy thận |

| Diltiazem

|

0.25 mg/kg i.v. bolus trong 5 phút, sau đó 5–15 mg/h | 60 mg ba lần ngày đến 360 mg (thải tiết chậm) lần ngày |

|

| Digitalis glycosides | |||

| Digoxin

|

0.5 mg i.v. bolus (0.75–1.5 mg trong 24 h trong các liều được chia ra)

|

0.0625–0.25 mg lần ngày

|

Nồng độ huyết tương cao kết hợp với các biến cố bất lợi.

|

| Digitoxin

|

0.4–0.6 mg

|

0.05–0.1 mg lần ngày

|

Kiểm tra chức năng thận trước khi khởi liều digoxin và liều thích ứng ở bệnh nhân bệnh thận mạn

|

| Các thuốc khác | |||

| Amiodaroned

|

300 mg truyền tĩnh mạch pha loãng trong 250 mL dextrose 5% trong

30–60 phút (tốt nhất là qua catheter tĩnh mạch trung tâm), sau đó là 900–1200 mg truyền tĩnh mạch trong 24 giờ pha loãng trong 500–1000 mL qua catheter tĩnh mạch trung tâm |

200 mg một lần mỗi ngày sau khi tải

Tải: 200 mg ba lần mỗi ngày trong 4 tuần, sau đó 200 mg mỗi ngày hoặc ít hơn tùy điều kiện (giảm các loại thuốc kiểm soát tần số khác theo tần số tim) |

Chống chỉ định trong trường hợp nhạy cảm với iốt.

Tác dụng phụ nghiêm trọng tiềm ẩn (bao gồm phổi, mắt, gan và tuyến giáp). Xem xét nhiều tương tác thuốc |

AF: rung nhĩ; CKD: bệnh thận mạn tính; HF: suy tim; i.v: tĩnh mạch; N/A Không có, không có sẵn hoặc không được phổ biến rộng rãi. Liều tối đa đã được xác định dựa trên tóm tắt đặc tính sản phẩm của từng loại thuốc.

a Tất cả các loại thuốc kiểm soát tần số đều chống chỉ định trong hội chứng Wolff–Parkinson–White; cũng như amiodarone tiêm tĩnh mạch.

b Các thuốc chẹn beta khác có sẵn nhưng không được khuyến cáo là liệu pháp kiểm soát tần số cụ thể trong AF và do đó không được đề cập ở đây (ví dụ: propranolol và labetalol).

c Không có dữ liệu về atenolol; không nên sử dụng trong suy tim có phân suất tống máu giảm hoặc trong thai kỳ.

d Phác đồ tải có thể thay đổi; liều lượng i.v. nên được xem xét khi tính toán tổng tải

7.1.4. Triệt phá nút nhĩ thất và cấy máy tạo nhịp

Việc triệt phá nút nhĩ thất và cấy máy tạo nhịp tim (‘triệt phá và tạo nhịp tim’) có thể làm giảm và điều hòa tần số tim ở những bệnh nhân AF (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S16). Quy trình này có tỷ lệ biến chứng thấp và nguy cơ tử vong dài hạn thấp.[468,488] Máy tạo nhịp tim nên được cấy ghép vài tuần trước khi phá hủy nút nhĩ thất, với tần số tạo nhịp tim ban đầu sau khi phá hủy được đặt ở mức 70–90 nhịp/phút. [489,490] Chiến lược này không làm xấu đi chức năng thất trái, [491] và thậm chí có thể cải thiện LVEF ở những bệnh nhân được chọn.[492,493] Cơ sở bằng chứng thường gồm những bệnh nhân lớn tuổi. Đối với những bệnh nhân trẻ tuổi, việc phá hủy và tạo nhịp tim chỉ nên được cân nhắc nếu nhịp tim vẫn không được kiểm soát mặc dù đã cân nhắc các lựa chọn điều trị thuốc và không dùng thuốc khác. Việc lựa chọn liệu pháp tạo nhịp (tạo nhịp thất phải hoặc tạo nhịp hai thất) phụ thuộc vào đặc điểm của bệnh nhân, tình trạng suy tim và LVEF.[187,494]

Ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng nghiêm trọng với AF vĩnh viễn và ít nhất một lần nhập viện vì suy tim, nên cân nhắc triệt phá nút nhĩ thất kết hợp với CRT. Trong thử nghiệm APAF-CRT (Ablate and Pace for Atrial Fibrillation-cardiac resynchronization therapy: Triệt phá và tạo nhịp cho rung nhĩ – liệu pháp đồng bộ hóa tim) trên quần thể có phức hợp QRS hẹp, phá hủy nút nhĩ thất kết hợp với CRT vượt trội hơn thuốc kiểm soát tần số đối với các kết quả chính (tử vong do mọi nguyên nhân và tử vong hoặc nhập viện do suy tim) và các kết quả phụ (gánh nặng triệu chứng và hạn chế về thể chất).[470,471] Tạo nhịp hệ thống dẫn truyền có thể trở thành chế độ tạo nhịp thay thế có khả năng hữu ích khi triển khai chiến lược tạo nhịp và phá hủy, sau khi tính an toàn và hiệu quả đã được xác nhận trong các RCT lớn hơn.[495,496] Ở những người nhận CRT, sự hiện diện (hoặc xuất hiện) AF là một trong những lý do chính khiến tạo nhịp hai thất không tối ưu.[187] Cải thiện tạo nhịp hai thất được chỉ định và có thể đạt được bằng cách tăng cường chế độ dùng thuốc kiểm soát tần số, phá hủy nút nhĩ thất hoặc kiểm soát nhịp, tùy thuộc vào đặc điểm của bệnh nhân và AF.[187]

7.2. Các chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp ở bệnh nhân AF

7.2.1. Các nguyên tắc chung và kháng đông

Kiểm soát nhịp tim đề cập đến các liệu pháp dành riêng để phục hồi và duy trì nhịp xoang. Các phương pháp điều trị này gồm chuyển nhịp tim, AAD, triệt phá qua catheter qua da, triệt phá nội soi và kết hợp, và các phương pháp phẫu thuật mở (xem Dữ liệu bổ sung trực tuyến, Bảng bằng chứng bổ sung S17). Kiểm soát nhịp tim không bao giờ là một chiến lược riêng lẻ; thay vào đó, nó luôn phải là một phần của phương pháp AF-CARE.

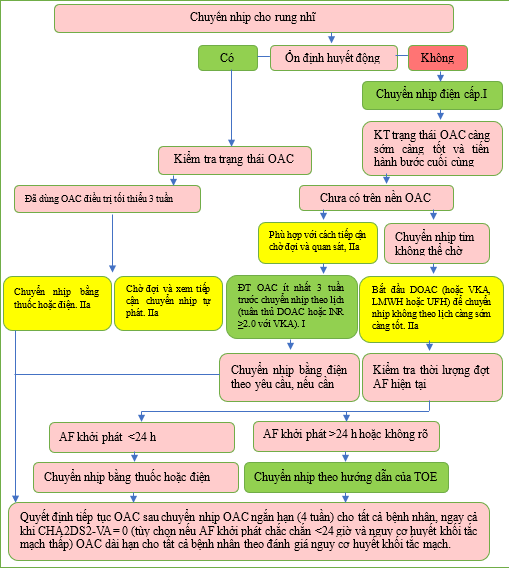

Đối với những bệnh nhân bị mất ổn định huyết động cấp tính hoặc nặng hơn được cho là do AF gây ra, nên tiến hành chuyển nhịp tim nhanh bằng điện. Đối với những bệnh nhân khác, nên cân nhắc phương pháp chờ đợi và theo dõi như một phương pháp thay thế cho chuyển nhịp tim ngay lập tức (Hình 12). Thử nghiệm Kiểm soát nhịp tim so với chuyển nhịp tim bằng điện 7 – Chuyển nhịp tim cấp thời so với chờ đợi và theo dõi (RACE 7 ACWAS) ở những bệnh nhân bị AF có triệu chứng khởi phát gần đây mà không bị ảnh hưởng huyết động cho thấy phương pháp chờ đợi và theo dõi để chuyển nhịp tim tự phát cho đến 48 giờ sau khi khởi phát các triệu chứng AF không kém hơn so với chuyển nhịp tim ngay lập tức trong 4 tuần theo dõi.[10]

Kể từ khi công bố các thử nghiệm mang tính bước ngoặt cách đây hơn 20 năm, lý do chính để cân nhắc liệu pháp kiểm soát nhịp dài hạn là giảm các triệu chứng của AF. [497–500] Các nghiên cứu cũ hơn đã chỉ ra việc thiết lập chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp sử dụng AAD không làm giảm tỷ lệ tử vong và bệnh tật khi so sánh với chiến lược chỉ kiểm soát tần số, [497–500] và có thể làm tăng tỷ lệ nhập viện. [457] Ngược lại, nhiều nghiên cứu đã chỉ ra các chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp có tác động tích cực đến chất lượng cuộc sống sau khi nhịp xoang được duy trì. [501,502] Do đó, trong trường hợp không chắc chắn về sự hiện diện của các triệu chứng liên quan đến AF, thì nỗ lực khôi phục nhịp xoang là bước đầu tiên hợp lý. Ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng, cần cân nhắc các yếu tố của bệnh nhân ủng hộ nỗ lực kiểm soát nhịp, bao gồm nghi ngờ bệnh cơ tim nhanh, tiền sử AF ngắn, tâm nhĩ trái không giãn hoặc sở thích của bệnh nhân.

Các chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp tim đã có sự phát triển đáng kể do kinh nghiệm ngày càng tăng trong việc sử dụng thuốc chống loạn nhịp an toàn, [17] sử dụng OAC thường xuyên, cải tiến trong công nghệ triệt phá, [503–509] và xác định và quản lý các yếu tố nguy cơ và bệnh đi kèm. [39,510,511] Trong thử nghiệm ATHENA (A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Parallel Arm Trial to Assess the Efficacy of Dronedarone 400 mg twice daily for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Hospitalization or Death from Any Cause in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation/Atrial Flutter: Thử nghiệm song song, mù đôi, có đối chứng giả dược để đánh giá hiệu quả của Dronedarone 400 mg hai lần mỗi ngày để phòng ngừa nhập viện tim mạch hoặc tử vong do bất kỳ nguyên nhân nào ở bệnh nhân bị rung nhĩ/rung nhĩ), dronedarone làm giảm đáng kể nguy cơ nhập viện do các biến cố tim mạch hoặc tử vong so với giả dược ở những bệnh nhân AF kịch phát hoặc dai dẳng. [512] Thử nghiệm CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation versus Standard Conventional Treatment in Patients With Left Ventricle Dysfunction and AF: Triệt phá qua catheter so với phương pháp điều trị thông thường chuẩn ở bệnh nhân rối loạn chức năng thất trái và AF) đã chứng minh chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp tim bằng phương pháp triệt phá qua catheter có thể cải thiện tỷ lệ tử vong và bệnh tật ở những bệnh nhân được chọn mắc HFrEF và thiết bị tim được cấy. [4] Ở giai đoạn cuối HFrEF, thử nghiệm CASTLE-HTx (Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure and Eligibility for Heart Transplantation: Triệt phá qua catheter để điều trị rung nhĩ ở bệnh nhân suy tim giai đoạn cuối và đủ điều kiện ghép tim) đã phát hiện ra, tại một trung tâm duy nhất, triệt phá qua catheter kết hợp với điều trị nội theo hướng dẫn đã làm giảm đáng kể tỷ lệ tử vong do bất kỳ nguyên nhân nào, cấy thiết bị hỗ trợ thất trái hoặc ghép tim khẩn cấp so với điều trị y tế. [513] Tuy nhiên, cùng lúc đó, thử nghiệm CABANA (Catheter Ablation versus Anti-arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: Triệt phá qua catheter so với liệu pháp thuốc chống loạn nhịp cho rung nhĩ) không thể chứng minh được sự khác biệt có ý nghĩa về tử suất và bệnh suất giữa triệt phá qua catheter và thuốc kiểm soát nhịp chuẩn và/hoặc các thuốc kiểm soát tần số ở những bệnh nhân AF có triệu chứng trên 64 tuổi hoặc dưới 65 tuổi có các yếu tố nguy cơ đột quỵ [3]. EAST-AFNET 4 (Early treatment of Atrial fibrillation for Stroke prevention Trial: Thử nghiệm điều trị sớm rung nhĩ để phòng ngừa đột quỵ) báo cáo việc thực hiện chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp trong vòng 1 năm so với chăm sóc thông thường làm giảm đáng kể nguy cơ tử vong do tim mạch, đột quỵ hoặc nhập viện do suy tim hoặc hội chứng mạch vành cấp ở những bệnh nhân trên 75 tuổi hoặc mắc các bệnh lý tim mạch. [17] Lưu ý, kiểm soát nhịp chủ yếu được thực hiện bằng thuốc chống loạn nhịp (80% bệnh nhân trong nhóm can thiệp). Chăm sóc thông thường bao gồm liệu pháp kiểm soát tần số; chỉ khi xảy ra các triệu chứng liên quan đến AF không kiểm soát được thì mới xem xét kiểm soát nhịp. Tất cả bệnh nhân trong thử nghiệm EAST-AFNET 4 đều có các yếu tố nguy cơ tim mạch nhưng đang ở giai đoạn đầu của AF, với hơn 50% có nhịp xoang và 30% không có triệu chứng khi bắt đầu nghiên cứu.

Dựa trên tất cả các nghiên cứu này, nhóm đặc nhiệm này kết luận việc triển khai chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp tim có thể được thiết lập một cách an toàn và cải thiện các triệu chứng liên quan đến AF. Ngoài việc kiểm soát các triệu chứng, việc duy trì nhịp xoang cũng nên được theo đuổi để giảm bệnh suất (morbidity) và tử suất (mortality) ở một số nhóm bệnh nhân được chọn.[4,17,502,513,514]

Bất kỳ thủ thuật kiểm soát nhịp tim nào cũng có nguy cơ cố hữu gây ra huyết khối tắc mạch. Bệnh nhân trải qua quá trình chuyển nhịp tim cần ít nhất 3 tuần dùng thuốc chống đông điều trị (tuân thủ DOAC hoặc INR >2 nếu VKA) trước khi thực hiện thủ thuật chuyển nhịp bằng điện hoặc thuốc. Trong các trường hợp cấp thời hoặc khi cần chuyển nhịp tim sớm, có thể thực hiện siêu âm tim qua thực quản (TOE) để loại trừ huyết khối tim trước khi chuyển nhịp tim. Các phương pháp tiếp cận này đã được thử nghiệm trong nhiều RCT. [319–321] Trong trường hợp phát hiện huyết khối, nên bắt đầu dùng thuốc chống đông điều trị trong tối thiểu 4 tuần, sau đó lặp lại TOE để đảm bảo huyết khối được giải quyết. Khi thời gian AF xác định dưới 48 giờ, thường cân nhắc chuyển nhịp mà không cần dùng OAC hoặc TOE trước thủ thuật để loại trừ huyết khối. Tuy nhiên, thời điểm khởi phát ‘xác định’ của AF thường không được biết và dữ liệu quan sát cho thấy nguy cơ đột quỵ/huyết khối tắc mạch thấp nhất trong khoảng thời gian ngắn hơn nhiều. [515–519] Nhóm đặc nhiệm này đã đạt được sự đồng thuận an toàn phải được đặt lên hàng đầu. Không khuyến cáo chuyển nhịp nếu thời gian AF dài hơn 24 giờ, trừ khi bệnh nhân đã được dùng thuốc chống đông điều trị ít nhất 3 tuần hoặc thực hiện TOE để loại trừ huyết khối trong tim. Hầu hết bệnh nhân nên tiếp tục OAC trong ít nhất 4 tuần sau khi chuyển nhịp. Chỉ những bệnh nhân không có yếu tố nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch và phục hồi nhịp xoang trong vòng 24 giờ sau khi AF khởi phát khi đó OAC sau chuyển nhịp mới là tùy chọn. Khi có bất kỳ yếu tố nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch nào, nên bắt đầu OAC dài hạn bất kể kết quả nhịp như thế nào.

Hình 12 Các phương pháp tiếp cận để chuyển nhịp ở bệnh nhân AF.

AF: rung nhĩ; CHA2DS2-VA: C: suy tim sung huyết, H: tăng huyết áp, A: tuổi ≥75 (2 điểm), D: đái tháo đường, S: đột quỵ/thiếu máu cục bộ thoáng qua/huyết khối động mạch trước đó (2 điểm), V: bệnh mạch máu, A: tuổi 65–74; h: giờ; LMWH, heparin trọng lượng phân tử thấp; DOAC, thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp; OAC, thuốc chống đông đường uống; TOE: siêu âm tim qua thực quản; UFH: heparin không phân đoạn; VKA: kháng vitamin K. ĐT: điều trị. Sơ đồ quy trình để ra quyết định chuyển nhịp AF tùy thuộc vào biểu hiện lâm sàng, thời điểm khởi phát AF, lượng thuốc chống đông đường uống và các yếu tố nguy cơ đột quỵ. a Xem Mục 6.

Bảng khuyến cáo 15 – Khuyến cáo cho các khái niệm chung trong kiểm soát nhịp (xem thêm Bảng bằng chứng 15)

| Các khuyến cáo | Classa | Levelbb |

| Chuyển nhịp bằng điện được khuyến cáo ở những bệnh nhân AF có tình trạng không ổn định huyết động cấp tính hoặc xấu đi để cải thiện kết quả tức thời cho bệnh nhân.[520] |

I |

C |

| Thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp được khuyến cáo ưu tiên hơn VKA ở những bệnh nhân đủ điều kiện bị AF đang trải qua chuyển nhịp để giảm nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch. [293,319–321,521] |

I |

A |

| Thuốc chống đông đường uống điều trị trong ít nhất 3 tuần (tuân thủ DOAC hoặc INR ≥2,0 đối với VKA) được khuyến cáo trước khi chuyển nhịp theo lịch trình đối với AF và cuồng nhĩ để ngăn ngừa huyết khối tắc mạch liên quan đến thủ thuật. [319–321] |

I |

B |

| Siêu âm qua thực quản được khuyến cáo nếu không cung cấp thuốc chống đông đường uống điều trị trong 3 tuần, để loại trừ huyết khối tim để cho phép chuyển nhịp sớm. [319–321,522] |

I |

B |

| Thuốc chống đông đường uống được khuyến cáo tiếp tục trong ít nhất 4 tuần ở tất cả bệnh nhân sau khi chuyển nhịp và dùng lâu dài ở những bệnh nhân có yếu tố nguy cơ huyết khối tắc mạch bất kể có đạt được nhịp xoang hay không, để ngăn ngừa huyết khối tắc mạch. [239,319,320,523,524] |

I |

B |

| Nên cân nhắc chuyển nhịp AF (bằng điện hoặc thuốc) ở những bệnh nhân có triệu chứng AF dai dẳng như một phần của phương pháp kiểm soát nhịp. [52,525,526] |

IIa |

B |

| Nên cân nhắc phương pháp chờ đợi để chuyển nhịp tự nhiên sang nhịp xoang trong vòng 48 giờ sau khi AF khởi phát ở những bệnh nhân không bị tổn thương huyết động như một phương pháp thay thế cho chuyển nhịp ngay lập tức. [10,525] |

IIa |

B |

| Nên cân nhắc triển khai chiến lược kiểm soát nhịp trong vòng 12 tháng sau khi chẩn đoán ở những bệnh nhân được chọn bị AF có nguy cơ bị các biến cố huyết khối tắc mạch để giảm nguy cơ tử vong do tim mạch hoặc nhập viện. [17,527] |

IIa |

B |

| Cần cân nhắc bắt đầu dùng thuốc chống đông trị liệu càng sớm càng tốt trong trường hợp chuyển nhịp không theo lịch trình đối với AF hoặc cuồng nhĩ để ngăn ngừa huyết khối tắc mạch liên quan đến thủ thuật. [319 321,528] |

IIa |

B |

| Cần cân nhắc thực hiện lại siêu âm qua thực quản trước khi chuyển nhịp nếu đã xác định được huyết khối trên hình ảnh ban đầu để đảm bảo huyết khối được giải quyết và ngăn ngừa huyết khối tắc mạch quanh thủ thuật. [529] |

IIa |

C |

| Không khuyến cáo chuyển nhịp sớm nếu không có thuốc chống đông thích hợp hoặc siêu âm qua thực quản nếu thời gian AF kéo dài hơn 24 giờ hoặc có thể chờ chuyển nhịp tự nhiên. [522] |

III |

C |

AF: rung nhĩ; DOAC: thuốc chống đông đường uống trực tiếp; INR: tỷ lệ chuẩn hóa quốc tế của thời gian prothrombin; VKA: thuốc kháng vitamin K.

a Class khuyến cáo.

b Mức độ bằng chứng

(Vui lòng xem tiếp trong kỳ sau)

TÀI LIỆU THAM KHẢO (458 – 707)

- Hess PL, Sheng S, Matsouaka R, DeVore AD, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, et al. Strict versus lenient versus poor rate control among patients with atrial fibrillation and heart

failure (from the get with the guidelines—heart failure program). Am J Cardiol 2020; 125:894–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.12.025 - Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM, et al.

Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med

2010;362:1363–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1001337 - Olshansky B, Rosenfeld LE, Warner AL, Solomon AJ, O’Neill G, Sharma A, et al. The

Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study: approaches to control rate in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1201–8. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.032

461. Ulimoen SR, Enger S, Carlson J, Platonov PG, Pripp AH, Abdelnoor M, et al.

Comparison of four single-drug regimens on ventricular rate and arrhythmia-related

symptoms in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:

225–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.09.020 - Tisdale JE, Padhi ID, Goldberg AD, Silverman NA, Webb CR, Higgins RS, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of intravenous diltiazem and digoxin for atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. Am Heart J 1998;135:739–47. https://doi.

org/10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70031-6

463. Khand AU, Rankin AC, Martin W, Taylor J, Gemmell I, Cleland JG. Carvedilol alone or

in combination with digoxin for the management of atrial fibrillation in patients with

heart failure? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1944–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2003.

07.020

464. Nikolaidou T, Channer KS. Chronic atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of medical

heart rate control management. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:303–12. https://doi.org/10.

1136/pgmj.2008.068908

465. Figulla HR, Gietzen F, Zeymer U, Raiber M, Hegselmann J, Soballa R, et al. Diltiazem

improves cardiac function and exercise capacity in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Results of the Diltiazem in Dilated Cardiomyopathy Trial. Circulation

1996;94:346–52. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.94.3.346 - Andrade JG, Roy D, Wyse DG, Tardif JC, Talajic M, Leduc H, et al. Heart rate and adverse outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a combined AFFIRM and AF-CHF

substudy. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.08.028

467. Weerasooriya R, Davis M, Powell A, Szili-Torok T, Shah C, Whalley D, et al. The

Australian Intervention Randomized Control of Rate in Atrial Fibrillation Trial

(AIRCRAFT). J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1697–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-

1097(03)00338-3 - Lim KT, Davis MJ, Powell A, Arnolda L, Moulden K, Bulsara M, et al. Ablate and pace

strategy for atrial fibrillation: long-term outcome of AIRCRAFT trial. Europace 2007;9:

498–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eum091 - Vijayaraman P, Subzposh FA, Naperkowski A. Atrioventricular node ablation and His

bundle pacing. Europace 2017;19:iv10–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eux263

470. Brignole M, Pokushalov E, Pentimalli F, Palmisano P, Chieffo E, Occhetta E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of atrioventricular junction ablation and cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and narrow QRS. Eur Heart

J 2018;39:3999–4008. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy555 - Brignole M, Pentimalli F, Palmisano P, Landolina M, Quartieri F, Occhetta E, et al. AV

junction ablation and cardiac resynchronization for patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and narrow QRS: the APAF-CRT mortality trial. Eur Heart J 2021;42:4731–9.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab569

472. Delle Karth G, Geppert A, Neunteufl T, Priglinger U, Haumer M, Gschwandtner M,

et al. Amiodarone versus diltiazem for rate control in critically ill patients with atrial

tachyarrhythmias. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1149–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/

00003246-200106000-00011

473. Hou ZY, Chang MS, Chen CY, Tu MS, Lin SL, Chiang HT, et al. Acute treatment of

recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter with a tailored dosing regimen of intravenous

amiodarone. A randomized, digoxin-controlled study. Eur Heart J 1995;16:521–8.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060945

474. Van Gelder IC, Wyse DG, Chandler ML, Cooper HA, Olshansky B, Hagens VE, et al.

Does intensity of rate-control influence outcome in atrial fibrillation? An analysis of

pooled data from the RACE and AFFIRM studies. Europace 2006;8:935–42. https://

doi.org/10.1093/europace/eul106

475. Scheuermeyer FX, Grafstein E, Stenstrom R, Christenson J, Heslop C, Heilbron B, et al.

Safety and efficiency of calcium channel blockers versus beta-blockers for rate control

in patients with atrial fibrillation and no acute underlying medical illness. Acad Emerg

Med 2013;20:222–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12091 - Siu CW, Lau CP, Lee WL, Lam KF, Tse HF. Intravenous diltiazem is superior to intravenous amiodarone or digoxin for achieving ventricular rate control in patients with

acute uncomplicated atrial fibrillation. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2174–9, quiz 2180.

https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a02f56

477. Perrett M, Gohil N, Tica O, Bunting KV, Kotecha D. Efficacy and safety of intravenous

beta-blockers in acute atrial fibrillation and flutter is dependent on beta-1 selectivity: a

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Clin Res Cardiol 2023;

113:831–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-023-02295-0 - Darby AE, Dimarco JP. Management of atrial fibrillation in patients with structural

heart disease. Circulation 2012;125:945–57. https://doi.org/10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA. 111.019935

479. Imamura T, Kinugawa K. Novel rate control strategy with landiolol in patients with cardiac dysfunction and atrial fibrillation. ESC Heart Fail 2020;7:2208–13. https://doi.org/

10.1002/ehf2.12879

480. Ulimoen SR, Enger S, Pripp AH, Abdelnoor M, Arnesen H, Gjesdal K, et al. Calcium

channel blockers improve exercise capacity and reduce N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels compared with beta-blockers in patients with permanent atrial

fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2014;35:517–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht429 - Connolly SJ, Camm AJ, Halperin JL, Joyner C, Alings M, Amerena J, et al. Dronedarone

in high-risk permanent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2268–76. https://doi.

org/10.1056/NEJMoa1109867 - Karwath A, Bunting KV, Gill SK, Tica O, Pendleton S, Aziz F, et al. Redefining betablocker response in heart failure patients with sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation: a machine learning cluster analysis. Lancet 2021;398:1427–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S0140-6736(21)01638-X

483. Koldenhof T, Wijtvliet P, Pluymaekers N, Rienstra M, Folkeringa RJ, Bronzwaer P, et al.

Rate control drugs differ in the prevention of progression of atrial fibrillation. Europace

2022;24:384–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euab191 - Champsi A, Mitchell C, Tica O, Ziff OJ, Bunting KV, Mobley AR, et al. Digoxin in patients with heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis

of 5.9 million patient years of follow-up. SSRN preprint. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2139/

ssrn.4544769.

485. Andrews P, Anseeuw K, Kotecha D, Lapostolle F, Thanacoody R. Diagnosis and practical management of digoxin toxicity: a narrative review and consensus. Eur J Emerg

Med 2023;30:395–401. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0000000000001065 - Bavendiek U, Berliner D, Dávila LA, Schwab J, Maier L, Philipp SA, et al. Rationale and

design of the DIGIT-HF trial (DIGitoxin to Improve ouTcomes in patients with advanced chronic Heart Failure): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:676–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1452 - Clemo HF, Wood MA, Gilligan DM, Ellenbogen KA. Intravenous amiodarone for acute

heart rate control in the critically ill patient with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Am J Cardiol

1998;81:594–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00962-4 - Queiroga A, Marshall HJ, Clune M, Gammage MD. Ablate and pace revisited: long term

survival and predictors of permanent atrial fibrillation. Heart 2003;89:1035–8. https://

doi.org/10.1136/heart.89.9.1035

489. Geelen P, Brugada J, Andries E, Brugada P. Ventricular fibrillation and sudden death

after radiofrequency catheter ablation of the atrioventricular junction. Pacing Clin

Electrophysiol 1997;20:343–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb06179.x - Wang RX, Lee HC, Hodge DO, Cha YM, Friedman PA, Rea RF, et al. Effect of pacing

method on risk of sudden death after atrioventricular node ablation and pacemaker

implantation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:696–701.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.01.021

491. Chatterjee NA, Upadhyay GA, Ellenbogen KA, McAlister FA, Choudhry NK, Singh JP.

Atrioventricular nodal ablation in atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012;5:68–76. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.111.

967810 - Bradley DJ, Shen WK. Overview of management of atrial fibrillation in symptomatic

elderly patients: pharmacologic therapy versus AV node ablation. Clin Pharmacol

Ther 2007;81:284–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.clpt.6100062 - Ozcan C, Jahangir A, Friedman PA, Patel PJ, Munger TM, Rea RF, et al. Long-term survival after ablation of the atrioventricular node and implantation of a permanent pacemaker in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1043–51. https://doi.

org/10.1056/NEJM200104053441403

494. Chatterjee NA, Upadhyay GA, Ellenbogen KA, Hayes DL, Singh JP. Atrioventricular

nodal ablation in atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of biventricular vs. right ventricular

pacing mode. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:661–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfs036 - Huang W, Su L, Wu S. Pacing treatment of atrial fibrillation patients with heart failure:

His bundle pacing combined with atrioventricular node ablation. Card Electrophysiol

Clin 2018;10:519–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccep.2018.05.016 - Huang W, Su L, Wu S, Xu L, Xiao F, Zhou X, et al. Benefits of permanent His bundle

pacing combined with atrioventricular node ablation in atrial fibrillation patients with

heart failure with both preserved and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am

Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005309. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.005309 - Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, Kingma JH, Kamp O, Kingma T, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial

fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1834–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021375 - Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Rosenberg Y, Schron EB, et al. A

comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N

Engl J Med 2002;347:1825–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021328 - Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Lilienthal J. Rhythm or rate control in atrial fibrillation—

pharmacological intervention in atrial fibrillation (PIAF): a randomised trial. Lancet

2000;356:1789–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03230-X - Roy D, Talajic M, Nattel S, Wyse DG, Dorian P, Lee KL, et al. Rhythm control versus

rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2667–77.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0708789

501. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Gizurarson S, Schwieler J, Jensen SM, Bergfeldt L, Kennebäck

G, et al. Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic medication on quality of life in

patients with atrial fibrillation: the CAPTAF randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;

321:1059–68. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.0335

- Mark DB, Anstrom KJ, Sheng S, Piccini JP, Baloch KN, Monahan KH, et al. Effect of catheter ablation vs medical therapy on quality of life among patients with atrial fibrillation:

the CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:1275–85. https://doi.org/10.

1001/jama.2019.0692

503. Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, De Paola A, Marchlinski F, Natale A, et al. Comparison

of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with

paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:333–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.2029

504. Calkins H, Reynolds MR, Spector P, Sondhi M, Xu Y, Martin A, et al. Treatment of atrial

fibrillation with antiarrhythmic drugs or radiofrequency ablation: two systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2009;2:349–61. https://doi.

org/10.1161/CIRCEP.108.824789

505. Jais P, Cauchemez B, Macle L, Daoud E, Khairy P, Subbiah R, et al. Catheter ablation

versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial fibrillation: the A4 study. Circulation 2008;118:

2498–505. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.772582 - Packer DL, Kowal RC, Wheelan KR, Irwin JM, Champagne J, Guerra PG, et al.

Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: first results

of the North American Arctic Front (STOP AF) pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:

1713–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.064 - Poole JE, Bahnson TD, Monahan KH, Johnson G, Rostami H, Silverstein AP, et al.

Recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation or antiarrhythmic drug therapy

in the CABANA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:3105–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.

2020.04.065

508. Mont L, Bisbal F, Hernandez-Madrid A, Perez-Castellano N, Vinolas X, Arenal A, et al.

Catheter ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drug treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation: a

multicentre, randomized, controlled trial (SARA study). Eur Heart J 2014;35:501–7.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht457

509. Scherr D, Khairy P, Miyazaki S, Aurillac-Lavignolle V, Pascale P, Wilton SB, et al.

Five-year outcome of catheter ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation using termination

of atrial fibrillation as a procedural endpoint. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:18–24.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001943

510. Lau DH, Nattel S, Kalman JM, Sanders P. Modifiable risk factors and atrial fibrillation.

Circulation 2017;136:583–96. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.

023163 - Sanders P, Elliott AD, Linz D. Upstream targets to treat atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll

Cardiol 2017;70:2906–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.043 - Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van Eickels M, Gaudin C, Page RL, Torp-Pedersen C, et al.

Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med

2009;360:668–78. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0803778 - Sohns C, Fox H, Marrouche NF, Crijns H, Costard-Jaeckle A, Bergau L, et al. Catheter

ablation in end-stage heart failure with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2023;389:

1380–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2306037 - Di Biase L, Mohanty P, Mohanty S, Santangeli P, Trivedi C, Lakkireddy D, et al.

Ablation versus amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients

with congestive heart failure and an implanted device: results from the AATAC multicenter randomized trial. Circulation 2016;133:1637–44. https://doi.org/10.1161/

CIRCULATIONAHA. 115.019406 - Nuotio I, Hartikainen JE, Gronberg T, Biancari F, Airaksinen KE. Time to cardioversion

for acute atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic complications. JAMA 2014;312:647–9.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3824

516. Garg A, Khunger M, Seicean S, Chung MK, Tchou PJ. Incidence of thromboembolic

complications within 30 days of electrical cardioversion performed within 48 hours

of atrial fibrillation onset. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2016;2:487–94. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.jacep.2016.01.018

517. Tampieri A, Cipriano V, Mucci F, Rusconi AM, Lenzi T, Cenni P. Safety of cardioversion

in atrial fibrillation lasting less than 48 h without post-procedural anticoagulation in patients at low cardioembolic risk. Intern Emerg Med 2018;13:87–93. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11739-016-1589-1

518. Airaksinen KE, Gronberg T, Nuotio I, Nikkinen M, Ylitalo A, Biancari F, et al.

Thromboembolic complications after cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: the

FinCV (Finnish CardioVersion) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1187–92. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.089

519. Hansen ML, Jepsen RM, Olesen JB, Ruwald MH, Karasoy D, Gislason GH, et al.

Thromboembolic risk in 16 274 atrial fibrillation patients undergoing direct current

cardioversion with and without oral anticoagulant therapy. Europace 2015;17:18–23.

https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euu189

520. Bonfanti L, Annovi A, Sanchis-Gomar F, Saccenti C, Meschi T, Ticinesi A, et al.

Effectiveness and safety of electrical cardioversion for acute-onset atrial fibrillation

in the emergency department: a real-world 10-year single center experience. Clin

Exp Emerg Med 2019;6:64–9. https://doi.org/10.15441/ceem.17.286 - Telles-Garcia N, Dahal K, Kocherla C, Lip GYH, Reddy P, Dominic P. Non-vitamin K

antagonists oral anticoagulants are as safe and effective as warfarin for cardioversion of

atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2018;268:143–8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.034

522. Klein AL, Grimm RA, Murray RD, Apperson-Hansen C, Asinger RW, Black IW, et al.

Use of transesophageal echocardiography to guide cardioversion in patients with atrial

fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1411–20. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200105

103441901

523. Brunetti ND, Tarantino N, De Gennaro L, Correale M, Santoro F, Di Biase M. Direct

oral anti-coagulants compared to vitamin-K antagonists in cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: an updated meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2018;45:550–6. https://doi.org/

10.1007/s11239-018-1622-5

524. Steinberg JS, Sadaniantz A, Kron J, Krahn A, Denny DM, Daubert J, et al. Analysis of

cause-specific mortality in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study. Circulation 2004;109:1973–80. https://doi.org/10.1161/

01.CIR.0000118472.77237.FA

525. Crijns HJ, Weijs B, Fairley AM, Lewalter T, Maggioni AP, Martín A, et al. Contemporary

real life cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: results from the multinational RHYTHM-AF

study. Int J Cardiol 2014;172:588–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.099 - Kirchhof P, Andresen D, Bosch R, Borggrefe M, Meinertz T, Parade U, et al. Short-term

versus long-term antiarrhythmic drug treatment after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation

(Flec-SL): a prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint assessment trial.

Lancet 2012;380:238–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60570-4 - Zhu W, Wu Z, Dong Y, Lip GYH, Liu C. Effectiveness of early rhythm control in improving clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMC Med 2022;20:340. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02545-4 - Stellbrink C, Nixdorff U, Hofmann T, Lehmacher W, Daniel WG, Hanrath P, et al.

Safety and efficacy of enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin and oral anticoagulants for prevention of thromboembolic complications in cardioversion of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: the Anticoagulation in Cardioversion using Enoxaparin (ACE)

trial. Circulation 2004;109:997–1003. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000120509.

64740.DC - Lip GY, Hammerstingl C, Marin F, Cappato R, Meng IL, Kirsch B, et al. Left atrial thrombus resolution in atrial fibrillation or flutter: results of a prospective study with rivaroxaban (X-TRA) and a retrospective observational registry providing baseline data

(CLOT-AF). Am Heart J 2016;178:126–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.05.007

530. Stiell IG, Eagles D, Nemnom MJ, Brown E, Taljaard M, Archambault PM, et al. Adverse

events associated with electrical cardioversion in patients with acute atrial fibrillation

and atrial flutter. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:1775–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2021.08.

018

531. Stiell IG, Archambault PM, Morris J, Mercier E, Eagles D, Perry JJ, et al. RAFF-3 Trial: a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial to improve care of acute atrial fibrillation and

flutter in the emergency department. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:1569–77. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.cjca.2021.06.016

532. Gurevitz OT, Ammash NM, Malouf JF, Chandrasekaran K, Rosales AG, Ballman KV,

et al. Comparative efficacy of monophasic and biphasic waveforms for transthoracic

cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. Am Heart J 2005;149:316–21.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.007

533. Mortensen K, Risius T, Schwemer TF, Aydin MA, Köster R, Klemm HU, et al. Biphasic

versus monophasic shock for external cardioversion of atrial flutter: a prospective,

randomized trial. Cardiology 2008;111:57–62. https://doi.org/10.1159/000113429

534. Inácio JF, da Rosa Mdos S, Shah J, Rosário J, Vissoci JR, Manica AL, et al. Monophasic and biphasic shock for transthoracic conversion of atrial fibrillation: systematic review and

network meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2016;100:66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

resuscitation.2015.12.009

535. Eid M, Abu Jazar D, Medhekar A, Khalife W, Javaid A, Ahsan C, et al. Anterior-posterior

versus anterior-lateral electrodes position for electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2022;43:

101129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2022.101129 - Squara F, Elbaum C, Garret G, Liprandi L, Scarlatti D, Bun SS, et al. Active compression

versus standard anterior-posterior defibrillation for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a prospective randomized study. Heart Rhythm 2021;18:360–5. https://doi. org/10.1016/j. hrthm.2020.11.005

537. Schmidt AS, Lauridsen KG, Torp P, Bach LF, Rickers H, Løfgren B. Maximum-fixed energy shocks for cardioverting atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2020;41:626–31. https://doi.

org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz585

538. Müssigbrodt A, John S, Kosiuk J, Richter S, Hindricks G, Bollmann A.

Vernakalant-facilitated electrical cardioversion: comparison of intravenous vernakalant

and amiodarone for drug-enhanced electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation after

failed electrical cardioversion. Europace 2016;18:51–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ europace/euv194

539. Climent VE, Marin F, Mainar L, Gomez-Aldaravi R, Martinez JG, Chorro FJ, et al. Effects

of pretreatment with intravenous flecainide on efficacy of external cardioversion of

persistent atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004;27:368–72. https://doi.org/

10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00444.x

540. Tieleman RG, Van Gelder IC, Bosker HA, Kingma T, Wilde AA, Kirchhof CJ, et al. Does

flecainide regain its antiarrhythmic activity after electrical cardioversion of persistent

atrial fibrillation? Heart Rhythm 2005;2:223–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.

11.014

541. Oral H, Souza JJ, Michaud GF, Knight BP, Goyal R, Strickberger SA, et al. Facilitating

transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation with ibutilide pretreatment. N Engl J

Med 1999;340:1849–54. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199906173402401 - Nair M, George LK, Koshy SK. Safety and efficacy of ibutilide in cardioversion of atrial

flutter and fibrillation. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:86–92. https://doi.org/10.3122/

jabfm.2011.01.080096

543. Bianconi L, Mennuni M, Lukic V, Castro A, Chieffi M, Santini M. Effects of oral propafenone administration before electrical cardioversion of chronic atrial fibrillation: a

placebo-controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:700–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S0735-1097 (96) 00230-6 - Channer KS, Birchall A, Steeds RP, Walters SJ, Yeo WW, West JN, et al. A randomized

placebo-controlled trial of pre-treatment and short- or long-term maintenance therapy with amiodarone supporting DC cardioversion for persistent atrial fibrillation. Eur

Heart J 2004;25:144–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2003.10.020 - Capucci A, Villani GQ, Aschieri D, Rosi A, Piepoli MF. Oral amiodarone increases the

efficacy of direct-current cardioversion in restoration of sinus rhythm in patients with

chronic atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2000;21:66–73. https://doi.org/10.1053/euhj.1999.

1734

546. Um KJ, McIntyre WF, Healey JS, Mendoza PA, Koziarz A, Amit G, et al. Pre- and posttreatment with amiodarone for elective electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2019;21:856–63. https://doi.org/10.

1093/europace/euy310

547. Toso E, Iannaccone M, Caponi D, Rotondi F, Santoro A, Gallo C, et al. Does antiarrhythmic drugs premedication improve electrical cardioversion success in persistent

atrial fibrillation? J Electrocardiol 2017;50:294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

jelectrocard.2016.12.004

548. Ganapathy AV, Monjazeb S, Ganapathy KS, Shanoon F, Razavi M. “Asymptomatic” persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation: a misnomer in selected patients. Int J Cardiol

2015;185:112–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.122 - Voskoboinik A, Kalman E, Plunkett G, Knott J, Moskovitch J, Sanders P, et al. A comparison of early versus delayed elective electrical cardioversion for recurrent episodes

of persistent atrial fibrillation: a multi-center study. Int J Cardiol 2019;284:33–7. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.068

550. Airaksinen KEJ. Early versus delayed cardioversion: why should we wait? Expert Rev

Cardiovasc Ther 2020;18:149–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779072.2020.1736563 - Boriani G, Diemberger I, Biffi M, Martignani C, Branzi A. Pharmacological cardioversion

of atrial fibrillation: current management and treatment options. Drugs 2004;64:

2741–62. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200464240-00003 - Dan GA, Martinez-Rubio A, Agewall S, Boriani G, Borggrefe M, Gaita F, et al.

Antiarrhythmic drugs–clinical use and clinical decision making: a consensus document

from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and European Society of

Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacology, endorsed by

the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) and

International Society of Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy (ISCP). Europace 2018;20:

731–732an. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eux373 - Gitt AK, Smolka W, Michailov G, Bernhardt A, Pittrow D, Lewalter T. Types and outcomes of cardioversion in patients admitted to hospital for atrial fibrillation: results of

the German RHYTHM-AF study. Clin Res Cardiol 2013;102:713–23. https://doi.org/10.

1007/s00392-013-0586-x

554. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, Kim YH, Saad EB, Aguinaga L, et al. 2017 HRS/

EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical

ablation of atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Europace 2018;20:157–208. https://

doi.org/10.1093/europace/eux275

555. Danias PG, Caulfield TA, Weigner MJ, Silverman DI, Manning WJ. Likelihood of spontaneous conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:

588–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00534-2 - Tsiachris D, Doundoulakis I, Pagkalidou E, Kordalis A, Deftereos S, Gatzoulis KA, et al.

Pharmacologic cardioversion in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a network

meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2021;35:293–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s10557-020-07127-1 - Grönberg T, Nuotio I, Nikkinen M, Ylitalo A, Vasankari T, Hartikainen JE, et al.

Arrhythmic complications after electrical cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: the

FinCV study. Europace 2013;15:1432–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eut106

558. Brandes A, Crijns H, Rienstra M, Kirchhof P, Grove EL, Pedersen KB, et al.

Cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter revisited: current evidence and practical guidance for a common procedure. Europace 2020;22:1149–61. https://doi.org/

10.1093/europace/euaa057 - Stiell IG, Sivilotti MLA, Taljaard M, Birnie D, Vadeboncoeur A, Hohl CM, et al. Electrical

versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute

atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomised trial. Lancet 2020;395:339–49.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32994-0

560. Alboni P, Botto GL, Baldi N, Luzi M, Russo V, Gianfranchi L, et al. Outpatient treatment

of recent-onset atrial fibrillation with the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach. N Engl J Med

2004;351:2384–91. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa041233 - Brembilla-Perrot B, Houriez P, Beurrier D, Claudon O, Terrier de la Chaise A, Louis P.

Predictors of atrial flutter with 1:1 conduction in patients treated with class I antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial tachyarrhythmias. Int J Cardiol 2001;80:7–15. https://doi.

org/10.1016/S0167-5273(01) 00459-4 - Conde D, Costabel JP, Caro M, Ferro A, Lambardi F, Corrales Barboza A, et al.

Flecainide versus vernakalant for conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Int J

Cardiol 2013;168:2423–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.02.006 - Markey GC, Salter N, Ryan J. Intravenous flecainide for emergency department management of acute atrial fibrillation. J Emerg Med 2018;54:320–7. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.jemermed.2017.11.016

564. Martinez-Marcos FJ, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Ortega-Carpio A, Fernandez-Gomez JM,

Santos JM, Camacho C. Comparison of intravenous flecainide, propafenone, and amiodarone for conversion of acute atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol

2000;86:950–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01128-0 - Reisinger J, Gatterer E, Lang W, Vanicek T, Eisserer G, Bachleitner T, et al. Flecainide

versus ibutilide for immediate cardioversion of atrial fibrillation of recent onset. Eur

Heart J 2004;25:1318–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2004.04.030 - Zhang N, Guo JH, Zhang H, Li XB, Zhang P, Xn Y. Comparison of intravenous ibutilide

vs. propafenone for rapid termination of recent onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Clin Pract

2005;59:1395–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00705.x - Camm AJ, Capucci A, Hohnloser SH, Torp-Pedersen C, Van Gelder IC, Mangal B, et al.

A randomized active-controlled study comparing the efficacy and safety of vernakalant

to amiodarone in recent-onset atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:313–21.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.046

568. Roy D, Pratt CM, Torp-Pedersen C, Wyse DG, Toft E, Juul-Moller S, et al. Vernakalant

hydrochloride for rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation: a phase 3, randomized,

placebo-controlled trial. Circulation 2008;117:1518–25. https://doi.org/10.1161/

CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723866 - Deedwania PC, Singh BN, Ellenbogen K, Fisher S, Fletcher R, Singh SN. Spontaneous

conversion and maintenance of sinus rhythm by amiodarone in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation: observations from the veterans affairs congestive heart failure

survival trial of antiarrhythmic therapy (CHF-STAT). The Department of Veterans

Affairs CHF-STAT Investigators. Circulation 1998;98:2574–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/ 01.cir.98.23.2574

570. Hofmann R, Steinwender C, Kammler J, Kypta A, Wimmer G, Leisch F. Intravenous

amiodarone bolus for treatment of atrial fibrillation in patients with advanced congestive heart failure or cardiogenic shock. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2004;116:744–9. https://

doi.org/10.1007/s00508-004-0264-0